COMMENTARY: What biases and blind spots do we have towards persons with disabilities? Engineer and social entrepreneur Ken Chua argues it's not that people with disabilities do not need help, but "there are many more forms of abilities than you think and preach."

Mothership and The Birthday Collective are in collaboration to share a selection of essays from the 2019 edition of The Birthday Book.

The Birthday Book (which you can buy here) is a collection of essays about Singapore by 54 authors from various walks of life. These essays reflect on the narratives of their lives, that define them as well as Singapore's collective future.

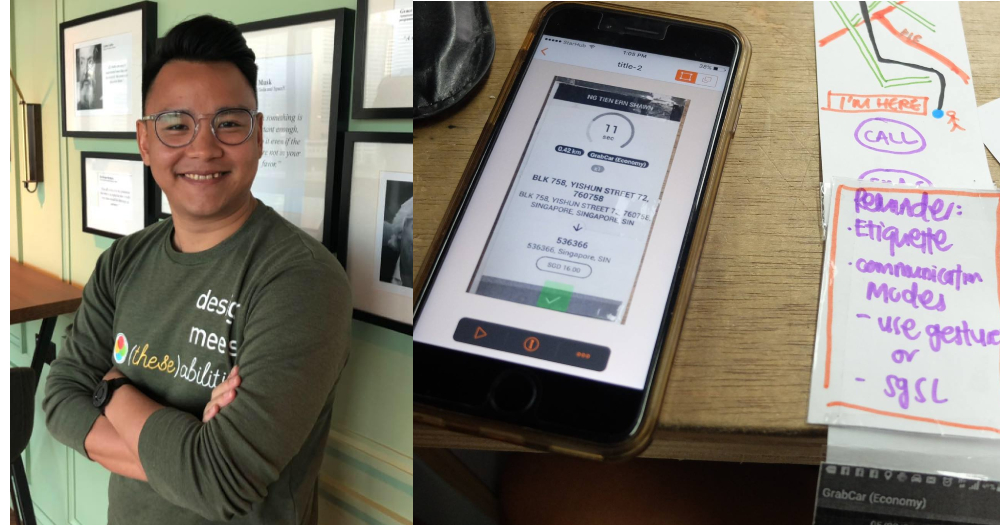

"A first for everything" is an essay contributed by Ken Chua, Director of (these)abilities, an inclusive design and technology agency that works with companies to build more inclusive products, services and environments that benefit persons with disabilities.

By Ken Chua

Pioneers come in various forms. In their most relatable, they lead the way for others. However, leadership isn’t easy because we usually can’t bring everyone along for the ride.

I wanted to detail how our country, with all its bouquets, blind spots and biases, has left Singaporeans with disabilities behind—along with all the groups that were marginalised in Singapore’s growth— and, crucially, how we can address that.

Biases and blind spots

I believe that every community welcomes others through a four-stage process: apathy, sympathy, empathy, empowerment, with some starting off on better footing than others.

I’m happy to observe that there is a lack of apathy in Singapore; we are generally keen to help our fellows out whenever we can. We don’t think twice when giving tissue sellers more than the cost price of the 3-pack; we donate readily on crowd donation platforms like giving.sg and GIVE.asia.

We also have an abundance of sympathy. But as a practitioner in the social impact space, I will be critical here and say that the abundance of sympathy is our main obstacle towards empathy.

Sympathy is where we feel for someone, seeing them as occupying a place perceived lesser than ours, often with less consideration for their livelihoods than parting with spare change in our wallet if it’s convenient.

Empathy is where we feel with someone, seeing them as equals. We have more consideration for the differences in circumstances that might have resulted in a segregation of our social standing. We donate less money but donate more time, consideration and effort.

Empathy is about caring in a smarter way. But our abundance of sympathy causes many of our biases and blind spots.

#1: Persons with disabilities don't always need our help

The first blind spot is that the disabled always need help.

While we may need help occasionally to overcome infrastructural barriers, we derive a sense of dignity and pride in fending for ourselves. We don’t want handouts but rather the opportunity to prove our worth.

For example, a blind person might ask for directions, but that isn’t an indication that the person is requesting for you to be a chaperone.

The assumption that we can’t make our own way is less valid than the assumption that we are simply unfamiliar with a place, just like any other person might be.

#2: Your help isn't always helpful

The second bias is that your help is always helpful. We don’t need you to make decisions for us. We want to prove our worth in ways unique to us, not those decided by you.

A fine example of this is open employment. Despite multiple job (re)designs, we’re still relegated to roles in call centres and administrative jobs even though we aspire to be bankers, programmers, scientists and managers.

Organisations think they’re doing the right thing, but because they think for us instead of with us, we’re caged into pre-determined roles they assume “our kind” can only undertake. This limits our growth potential.

There are great hiring models in other parts of the world, such as blind hiring (a la The Voice) and a probationary period where we get the responsibility and opportunity to design our work environments specific to how we function best.

These are not practised in Singapore; instead, everything is decided for us—how we are assessed, our environment, our jobs, even how colleagues have been primed on how to interact with us.

#3: The idea that persons with disabilities cannot offer help

The third bias is that we can’t offer help—whether to ourselves or to others.

We have always been seen as beneficiaries, the ones for whom concessions are made. We aren’t valued enough to be at the decision-making table but are the subjects of decisions nonetheless.

In this perspective, our value is only in increasing the perceived moral value of the organisations that help us.

I’m not suggesting that we don’t need help; we do. But we would prefer you seek our counsel as to what opportunities would allow us to best grow into high-performing individuals. There are many more forms of abilities than you think and preach.

How people get left behind

Even today, websites of Singaporean companies and government agencies are not blind friendly because we only have four visually impaired computer scientists in Singapore.

Why? Because computing schools still scan pages out of textbooks—something our screen-reading software can’t pick up.

Dickson Tan, NUS School of Computing’s first visually impaired student on the Dean’s List, has shared with me how lobbying for professors to ensure that digitised copies of course material are in accessible formats can get tiring as there is no standard from the university on accessible content formats for academic documents.

Yet, when included, people with disabilities such as Professor James Spilker Jr can do great things.

As a legally blind student, James received accessible education support from Stanford University that would later enable him to become part of the team that invented Global Positioning Systems (GPS).

Access to news and media for the Deaf through a sign language interpreter prioritises events such as the Singapore Budget, General Election campaigns and court hearings because we only have five full-time sign language interpreters.

As such, Deaf friends such as Lisa Loh can’t decide on a whim to visit a poetry recital or an important talk or conference that interests her.

Fortunately, this is improving slightly, at least in local theatre, where most productions (e.g., W!ld Rice, Singapore Repertory Theatre, Pangdemonium) plan for at least one show with sign language interpretation (for the Deaf) and are warming up to the idea of audio descriptions (for the blind) in order to include any theatre fan regardless of abilities.

Public transport

Most users of electric wheelchairs can’t use any form of ride-hailing service other than London cabs and specialised wheelchair-accessible vehicles (that cost more than 50 Singapore dollars per personal trip).

Until recently, only one wheelchair user could board a public bus at a time, even if we were travelling in groups; this is because we are included only in half-day focus- group discussions rather than high-level discussions on public transport procurement.

Anecdotes like these depict how no-brainers to people with disabilities go unaddressed due to societal blind spots.

But if you seek to truly understand, not judge, you could empower rather than pacify us. Authentic inclusion of persons with disabilities is clearly underdeveloped, but I certainly hope it’s underway.

Contributing to society in our daily interactions

Other than helping us, one might wonder how we, the seemingly disabled, help society. In fact, we already have—including our contributions as catalysts for innovation in our daily interactions.

Voice dictation, for example, was pioneered in the 1980s as an accessibility feature; today, millions of non-disabled people use it daily through voice assistants like Siri and Google Assistant.

The same goes for word prediction, a technology developed for people who have trouble typing on traditional computers—millions of people now use it under the guise of a smartphone’s autocomplete function.

In 1995, Wayne Westerman’s painful encounters with tendonitis highlighted the need for computers—which used way stiffer mechanical keys 20 years ago—with zero-force input in order to increase his endurance for typing on a computer. This resulted in the development of the earliest algorithms for multi-finger gestures on the touchscreens in our smartphones.

In 2009, Ken Harrenstien, who has been Deaf since a young age and passionate about making speech more accessible to his community, debuted automated captioning on Youtube— something that non-native-speaker fans of Korean drama can appreciate.

In 2016, Google released an accessibility feature, Voice Access, for its mobility-challenged users to control their smartphones solely with their voice—it’s hard to see how those without disabilities, too, wouldn’t want to use such features when in bed or when driving.

These persons with disabilities deserve recognition as the original life-hackers; our motivation to innovate arises from our need to navigate a world that was not built with us in mind.

We offer fresh lived experiences: although we may have slightly different ways of living, we’re still part of the human condition.

This allows us to add value, not just in building products that benefit us but in creating a fresh and more liveable experience for everyone.

Hopefully, this will allow society to view us in a new light—not as beneficiaries, but as equals.

I do not have a physical disability. So why do I address persons with disabilities as “We”?

If you were to run a quick social media search on me, you would realise that I do not have a physical disability. So, why do I address persons with disabilities as “We”?

I will never claim to fully understand disability through the lens of actually having one, but socially speaking, I grew attuned to disability as a friend and confidante of some people with disabilities—which goes to show that it’s not just those who face disability on a daily basis who should fight the good fight.

Though there are a billion persons with disabilities around the world, the number of people impacted by their conditions, which includes their family, friends and caretakers, doubles in size.

Anyone reading this could be affected by disability: be it by its injustice, the joy of its people or chasing the dream of growing into a truly inclusive society.

Such a society is something we can all pioneer together.

Have an interesting perspective to share or a commentary to contribute? Write to us at [email protected].

If you happen to be in the education space and think this essay may be suitable as a resource (e.g. for English Language, General Paper or Social Studies lessons), The Birthday Collective has an initiative, "The Birthday Workbook", that includes discussion questions and learning activities based on The Birthday Book essays. You can sign up for its newsletter at bit.ly/TBBeduresource.

Top photo via these(abilities)/FB

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.