Walking into the oncology ward on the seventh floor of Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital on a Tuesday afternoon, I am immediately greeted by the wide smile and warm welcome of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Narindarjeet — known as Narin by most people — is a nurse manager in the oncology ward. Despite having started her shift at 7am, the 58-year-old comes across as bubbly and genuine, and I immediately feel a sense of familiarity and comfort speaking with her.

Narin, who has been a nurse for 40 years, shares that she loves talking to people, and doesn’t have any problems forming relationships or approaching others.

Laughing, she says, “My children always tell me, ‘Ma, talk less!’”

Narin’s warmth and what she says other people call her “motherly charm” have been integral to her specific passion, and how she spent almost two decades of her work as a nurse: in palliative — or end-of-life — care.

Nursing considered a “dirty” job, but wanted to be one

Narin’s four-decade-long journey as a nurse began back in 1980. The then 18-year-old was offered a nursing position after she finished her first year of A-Levels.

Narin was relief-teaching at that time though and had also been offered a teaching position, which her father encouraged her to take up instead.

Teaching was viewed as more prestigious, Narin says, and her father felt that nursing was too dirty of a job, which also involved long and late working hours.

However, Narin was taken by the nobleness of the nursing profession, as well as the fact that it allowed her to interact closely with patients.

"I used to look at all the nurses in white uniform — they looked so pure, so sweet. I was never ladylike, but it was very noble-like!"

And so, she began her career as a nurse at Singapore General Hospital (SGH).

Narin as a young nurse. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin as a young nurse. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin (front row, second from left) with her fellow nurses at SGH. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin (front row, second from left) with her fellow nurses at SGH. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Within two years of joining the workforce as a nurse, Narin suffered the heart-breaking deaths of both of her parents — first her father passed away from a heart attack in 1981, and her mother lost her life to breast cancer the following year.

The loss of her parents struck Narin deep, evident by how her voice, laced with emotion, tenses up a bit, as she speaks about her loss:

"I was 20 when I lost both my parents. I was very bad, because, imagine you lose one parent. I lost both within the year-and-a-half.

[...]

It was tough. But these are times that make you even stronger to face a lot of challenges."

Narin with her parents. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin with her parents. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Her parents’ deaths impacted the way that she regarded patients from then on:

"In my patients, I always look at them as somebody's loved one. And maybe, because of that, over the years, things I could not do for my parents, I think, I tend to them for my patients.

I look at them as, maybe, my parents. It has been, all this while, that way. You know, I couldn't give that care to my parents, but here is someone who needs it."

This is a lesson that she passes on to the nurses she supervises as well:

"They are not nobody. They are somebody's loved ones. And when they are in your care, take them as your loved ones. Treat them how you would treat your loved ones."

A lifetime of growth and learning

Narin’s journey as a nurse at SGH lasted 27 years, and during that time, she went back to school — not once, not twice, but five times — to continue improving her skills and qualifications.

In her first few years, Narin first took courses to become an enrolled nurse, and then continued her studies to reach the next tier: a registered nurse.

In 1991, she went back to school to study oncology — the branch of medicine that deals with cancer, the disease that claimed the life of her mother.

Why did she keep going back to her studies? Narin explains simply that she wanted to develop herself. In addition, she understood that doing so would give her more authority in her work:

"You know, when you have a paper, you become an expert. So nobody argues with you, nobody fights.

Because the one thing that I always used to hear is, 'Is that your expertise?' 'Are you an expert?'"

In 2004, Narin heard about the Advanced Diploma In Health Science (Palliative Care) at Nanyang Polytechnic (NYP) — the first of its kind offered in Singapore — and signed up to be part of its first batch. She graduated with her diploma in 2005.

Then, in 2015, 35 years after she became a nurse, Narin took her biggest education step yet — with the encouragement of her family, she enrolled at Kaplan to earn her Bachelor of Nursing from Griffith University.

One of the reasons, she says, is that she wanted to make her parents proud.

"Even though they are no longer around after so many years, wherever my parents are, they will be so happy seeing their daughter wearing the graduation [gown] and everything."

Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin also wanted to be a role model to her children, and they in turn were extremely supportive of her. In fact, it was her children who pushed her to enrol in the programme, as they knew that she had always dreamt of being a graduate, but had never gotten a chance:

"My whole life, I was actually just concentrating on my children, at the same time doing all my small, small studies."

Still, she wondered whether she was too old to go back to school.

"And then I said, 'Okay, but at this age?' I was about 54. Then [my children] said, 'Ma, you are never too old to study."

She jokes that now she can use her degree to her advantage when talking to her children:

“So now I can very confidently tell them, ‘Mum is a graduate. You want to talk to me, be a graduate!”

A couple years after earning her degree, Narin realised that she wanted to shift back into an acute care hospital environment, which is when she joined Mount Elizabeth Hospital in 2019 as a nurse manager in the oncology ward.

Passion for palliative care

And while all of Narin's courses enriched her work one way or another, it was the Nanyang Polytechnic course that provided the groundwork for her passion for palliative care.

Prior to starting the course, Narin had already been doing end-of-life care with patients as part of her job scope in the oncology ward. And while the the hospital offered some small courses in palliative care, Narin wanted to do more:

"So I went for that course, then I felt not enough. I need to specialise further. And I think that was, maybe, a calling."

Then, in 2007, two years after getting her diploma from NYP, Narin switched from the acute care hospital setting of SGH to Dover Park Hospice.

Her time there, she tells me, was "a very, very beautiful moment" for her.

Narin’s passion and tenderness for palliative care, and the patients she works with, shines through clearly from the way that she speaks about her work.

"People always have this concept that hospice is a place to die. It's a 'death house'. But that's not the case.

There are a lot of things that are being done in the hospice that people are not aware of. Like how to live life till the very end, when cure is not something that can be achieved? ...What else can you do?"

While acute care focuses on finding a cure for ailments, palliative care focuses instead on comfort, she explains.

She and the other staff would put together activities for patients, in order to allow them to live their lives in as meaningful a way as possible. These activities — including birthday celebrations, art and music therapy, or even a viewing of the sunrise and sunset — create meaningful moments and memories for patients.

Narin even recalls bringing in the Registry of Marriages (ROM) at the request of patients who wished to be married, and hosting the marriage of a long-time couple in the hospice’s auditorium in front of their families.

The philosophy of hospice work, Narin explains, is that “instead of adding days into your life, you add life into your days.”

This personal, heartfelt approach is something that she tries to encourage other nurses to apply to their work with patients, whether or not they work in palliative care.

During her time at Dover Park Hospice, she would pass on her mantra to nurses who were on attachment. Similarly, now at Mount Elizabeth, she also conducts lessons for other nurses in how to provide this kind of care.

Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Most memorable patient

Narin’s approach to her work has inevitably allowed her to form close relationships with her patients.

One of her most memorable patients was an 11-year-old boy with cancer, with whom she developed a close emotional bond while caring for him in the oncology ward at SGH.

“I don’t know how… [but] to him, I was his mother or I was his saviour, I don’t know. But this boy really affected me so much.”

The boy was terminally ill, and there was nothing else that could be done for him, so he was moved out of the hospital and into hospice care.

Narin recounts how he would stretch out his arms to be held by her when she walked into the room to visit him.

She explains that after hearing that he was not happy at the hospice centre, she knew he needed to be brought back to the hospital to be better cared for.

She called up the doctor to explain the situation, and received his approval to have the boy move back to SGH.

The night that the boy returned to the hospital, Narin cared for him. However, the next day, the boy passed away.

“[His death] had a very big impact on me,” Narin says, her voice breaking and her eyes tearing up. “It was like a part of me that was living.”

Support for families of palliative patients

In addition to treating her patients like her own family members, Narin also explains the importance of providing support to the families of her patients.

Families need to be validated that they made the right decision and did their best with their loved ones’ treatment, she says, adding that when a patient passes, it is usually the family who is left behind with the grief.

Reminding the families that they have done a good job, and that they have done their best can help them through the grieving process, says Narin.

Prior to a patient's death, Narin would sit down with their family to have an honest conversation about what is to come.

“I’m quite brave, enough to tell them that the next 48 hours or 72 hours is not looking very good.”

She also gives the families advice on how they can make their loved one's last days more comfortable:

“Just be there, instead of just all sitting and looking. So I gave them small, small tasks to do: hold hands, pray, if there is a Buddhist chanting, do that. They can always put music. Small things like cleaning the mouth, cleaning the eyes.”

Narin’s relationship with the family also doesn’t end with the death of the patient, as she makes the effort to attend patients' wakes in her free time, and is still in contact with many of her patients' families.

Meaningful job, but has its challenges

Narin’s nursing work extends even past her job, as, prior to Covid-19, she was volunteering her time regularly with her past workplace, Dover Park Hospice.

In addition, she and a number of other medical professionals also provide medical support to the Sikh community through the Singapore Khalsa Association, holding health screenings at community events.

Narin (second from right) and other volunteers. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin (second from right) and other volunteers. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

These ways of spending her spare time — including attending her patients' wakes and calling patients — give her job satisfaction and a sense of achievement.

Still, Narin admits that, as rewarding as she has found nursing to be, there can be very tough moments, such as the late nights and the missed family holidays, which at times come with no "thank you's" in return.

"Sometimes in your busy day, you say, 'What the heck am I doing in this line?! Do I deserve this?'

Then you go to the back, and you cry. You cry a lot."

And while she has certainly seen more appreciation for nurses during this Covid-19 season, particularly when compared to her early years in nursing, Narin feels that there can be more appreciation for the work that nurses do.

"We nurses are humans as well. And we have a heart. We actually sacrifice a lot for people that we take care of.

[...]

So I think, sometimes, we deserve a little bit more. Sometimes it doesn't hurt too much to just say thank you.

[...]

Just a little bit of appreciation, a little bit of smile, a little bit of thank you, makes our day. That's all we need."

Still, Narin reiterates her love for her job, as well as the gratitude that she has for the constant support from her family — her husband, two sons, and one daughter.

Narin with her family. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

Narin with her family. Photo courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur.

And she doesn’t plan on stopping her good work anytime soon, as she continues to train the next generation of nurses.

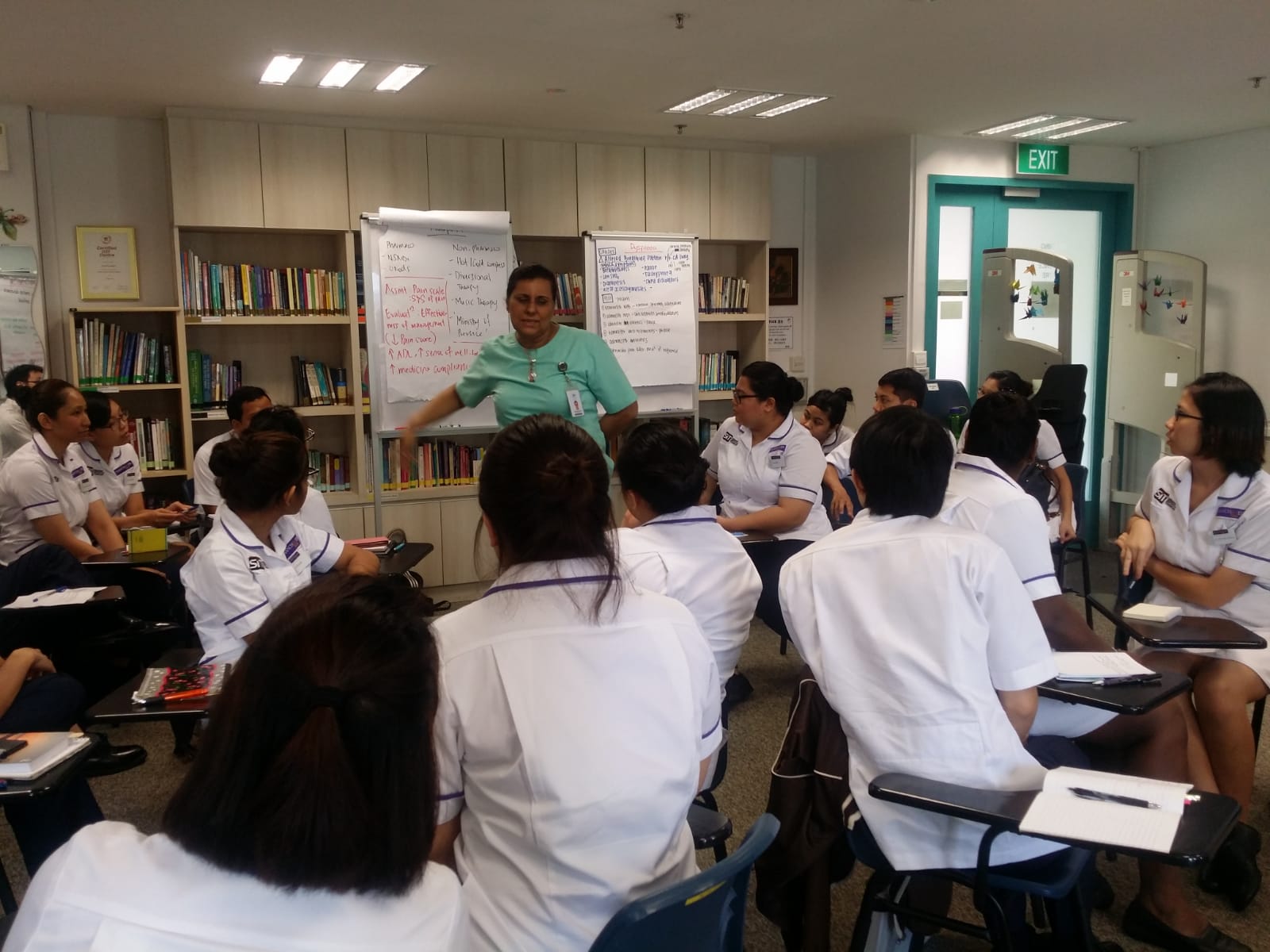

Narin (second from right) with some of her nurses. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Narin (second from right) with some of her nurses. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Laughing, she says that she is waiting for her son, who is studying medicine, to graduate and start working so that she can retire: "I don't know how long I'm going to work — maybe two years, three years?"

But she gets a bit more serious in her next sentence, and states genuinely, "but I don't think I can ever stop working."

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top photos courtesy of Narindarjeet Kaur (left) and by Jane Zhang (right). Some quotes have been edited for clarity.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.