"Every opportunity to me, it's a privilege, it's not an entitlement. And so I always show up completely for it, wholeheartedly for it."

These were enthusiastic words said to me by then-Nominated Member of Parliament (NMP) Anthea Ong over a Zoom call on a Tuesday afternoon in June.

And the more we talked, the more I could see how this mindset led to her speaking the most number of times on bills, and filing the highest number of parliamentary questions out of the nine NMPs in her cohort, according to CNA — truly showing up wholeheartedly for her role.

Many people may know her for consistently speaking up about issues surrounding mental health, migrant workers, and other marginalised communities, and — quite notably in the past few months — asking whether the government would consider apologising to the migrant workers for the Covid-19 situation in dormitories.

But she never envisioned herself sitting in Parliament, as politics was never something that she dreamt of partaking in, nor was it the place she felt she could make change. Instead, she spent decades working as a high-flying corporate woman, and then doing a full-180 degree turn to devoting her life to working directly with issues on the ground.

So, what was Ong's path to becoming an NMP like? What pushed her to accept the position and speak up for the issues that she did? And now that it's all over, what does she think?

Grew up when “being a girl was not very welcome”

Ong shared two aspects of her childhood that stood out as “big moments” in her life, which shaped her perspective on the issues she cares about deeply today.

First, being born a girl, "in a time, in a different Singapore, where being a girl was not very welcome.”

Her Chinese name — 王丽婷 — given by her grandfather, reflected this attitude; the third character 婷 (ting) sounds like the Chinese word for “stop”, as it was considered not good that the first two children of Ong’s father, the eldest son in his family, were both girls.

This contributed to Ong's involvement with women’s groups and women issues, she explained.

The second notable aspect of Ong’s childhood was growing up with an eye defect. Her family thought that she was developmentally challenged. She was also teased in school and called names such as "stupid" and "retarded".

Those two moments, she said, greatly influenced who she is now:

"For a long time now, I know why there's always this innate need to understand, but also to speak up for, those on the margin.

Because I was so wanting to be accepted, so feeling rejected, feeling so marginalised for so many years."

Achieving traditional success, followed by collapse

The teasing only stopped once she began studying especially hard and excelling in school, Ong said, culminating in her attaining a business degree at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

After graduation, Ong went into banking, and by 25, she was already the director of an international company:

"So, I did well. It was a very illustrious career I had. In the words of traditional success, I was very successful, very fast and furiously."

And she might have gone on following that path, Ong said, if not for a "major collapse" in her life when she was in her late-30s. A failed business and a painful divorce left her in a deep depression, with only S$16 in her bank account at one point.

"It was such a deep state of despair I was in, with a heart so broken, with a marriage completely in pieces, and along with that, a broken business which was really all of what I was working for...

I did see a psychiatrist who deemed that my depression was not clinical. But the pain was real. It was very dark. It was very deep. At one time I even contemplated the distance between my 18th floor apartment and the ground. That's what we call now suicide ideation.

This extremely difficult part of her life, she said, is what motivated her to speak up for those with mental health issues, those with disabilities, as well as vulnerable and marginalised groups.

"I wasn't just speaking about them because they were trendy or anything, but there was actually a personal context to that, that shaped how important these issues were for me to speak up for in Parliament, and why I have been doing work in these areas in the last 15 years, even before being an NMP."

Becoming socially involved

During that time, Ong began thinking about her values:

"In that pain, that very deep, excruciating pain and suffering, I started to question, you know, what do I want to put my strengths and my gifts to? And what really mattered?"

From there, she started down the path of being deeply involved in the "people sector" over the past 15 years — both as an active volunteer and as a social entrepreneur.

At the time, however, Ong did not have her eye on politics.

She told me:

"Never, ever in my life did I even think for a moment I would be in politics. Not at all!

I mean, people may have dreams and all that. [But] this was so far away from anything I've ever dreamt of!"

Instead, she worked close to the ground, founding and co-founding a number of community projects, including social enterprise Hush TeaBar, Singapore’s first silent teabar to bring silence and awareness to the workplace, and which employs hearing-impaired employees.

She also co-founded A Good Space in 2017, now a co-operative and a community initiative to support social changemakers to raise awareness on social challenges and then coming together to address them ground-up efforts.

At an A Good Space event. Photo via Facebook / A Good Space.

At an A Good Space event. Photo via Facebook / A Good Space.

Ong with A Good Space. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Ong with A Good Space. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Asked to be NMP candidate twice

Back in 2011, Ong was asked if she wanted to be nominated as an NMP candidate. However, Ong turned it down, because at the time she thought that politics was not the place for her to do her work.

"I remember even thinking, what change do they make even in Parliament? Especially as I was so much closer to the ground."

Then, in 2018, calls for nominations for NMP candidates opened up again.

The National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre (NVPC), who also nominated former NMP Kuik Shiao Yin, came to Ong, initially asking her whether she had suitable candidates in mind, but later asking if she would like to be fielded instead.

Ong realised that this time, she felt different about the ask:

"At that moment, even though I said, 'What?! I thought I was coming up with candidates for you'...

... then it started to sort of settle in, and I said, 'Oh, okay. Let me think about it'."

The first time she was asked to be a candidate for NMP, Ong had felt that she didn't have deep experience on the ground, nor that her community leadership experience "was really essential or significant".

Ong recalls how the NVPC told her that she would be perfect for the role, given her dual experience working in the corporate sector and being extremely immersed in the social sector.

"I think everything has a ripening moment, that season for everything," Ong told me.

Her previous mindset — about politics not being the place she wanted to make change — had also shifted:

"I think because I'd worked so deeply on the ground, I also saw that many social issues, as much as we can come in from the ground-up to try to make some changes, I also saw that many of these issues — particularly like mental health disability and lower income households — they are so perpetual, they are so eternal.

... It's just very obvious that it's because it needs a more structural shift, which means that it needs to be a policy change. The change has to be at the highest level."

Ong shared how she found out she had been chosen as one of the nine NMPs, out of 48 candidates:

"It was excitement. It was feeling a lot of exhilaration, a lot of excitement, a lot of enthusiasm. And, you know, maybe also a bit of shock, because I wasn't expecting it."

Maiden speech and mindfulness exercise

Ong and eight other NMPs were appointed into Parliament by President Halimah Yacob on Sep. 26, 2018.

Photo via Facebook / Halimah Yacob (MCI Photo by LH Goh).

Photo via Facebook / Halimah Yacob (MCI Photo by LH Goh).

Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

The NMPs attended their first Parliament on Oct. 1, 2018.

Ong at her first sitting of Parliament, before the sitting convened. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Ong at her first sitting of Parliament, before the sitting convened. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

While Ong didn’t speak in her first sitting, the bill being discussed during the second sitting was right up Ong's alley: an Employment (Amendment) Bill.

"Voilà! It's meant to be!" She said of the coincidence.

In that debate, Ong spoke about mental well being at the workplace, and pushed for changes to the Workplace Health and Safety Act, advocating for the inclusion of psychosocial health and safety on top of the physical aspects — including for our migrant workers.

The most momentous part of that speech, which Ong says will "always go down in history" for her, was when she opened her maiden speech by asking the entire Parliament to do a mindfulness breathing exercise with her.

"It was something I was so, so worried [about] if I was out of line, but I was so compelled to. There was something in me that said we should, and it was so powerful, because you could literally hear, for that 10 seconds or so, complete silence in the chamber and just the sounds of breathing."

On one hand, she said, the exercise was helpful to herself, given that it was her first speech in Parliament. On the other hand, Ong, who has been practising twice-daily meditation for 15 years, wanted to bring her true self into her role:

"I really wanted, you know, to bring my most authentic self to the hallowed chamber, which is [that] we must be here with the fullest presence, because what we do in this chamber affects every Singaporean, as well as the planet."

Ong meditating by a waterfall. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Ong meditating by a waterfall. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Purpose is to give voice to others

As NMPs are non-partisan and not worried about votes, they play an incredibly important role in democracy, said Ong:

"It's really important to really take advantage of this non-partisanship position, to really bring up issues that are deemed to be sensitive by the elected MPs — and I mean opposition and ruling party alike, because they have to watch the majority on the ground."

She also realised, after talking to some of the MPs, that they didn't seem to have as much capacity to look at "national issues" and non-voting constituents — such as mental health, climate change, and migrant workers' issues — since they have so many residents and local issues within their constituencies to look after.

"So I felt also that there is this heavy responsibility that I hold to address national issues, that's more about the future and systemic challenges that we have."

Instead of constituents, Ong has community groups that she lends her voice to, she explained.

"Every bill that I speak up for, every issue, every parliamentary question, they have been either from the community groups that I work with — they'll reach out to me, or I know because I've been working with them for years and years — none of them are really just my own voice."

And Ong did a great deal of lending her voice.

Between Oct. 2018 and Feb. 2020, Ong spoke up at every single Parliament sitting; she filed 92 parliamentary questions and spoke on 23 bills.

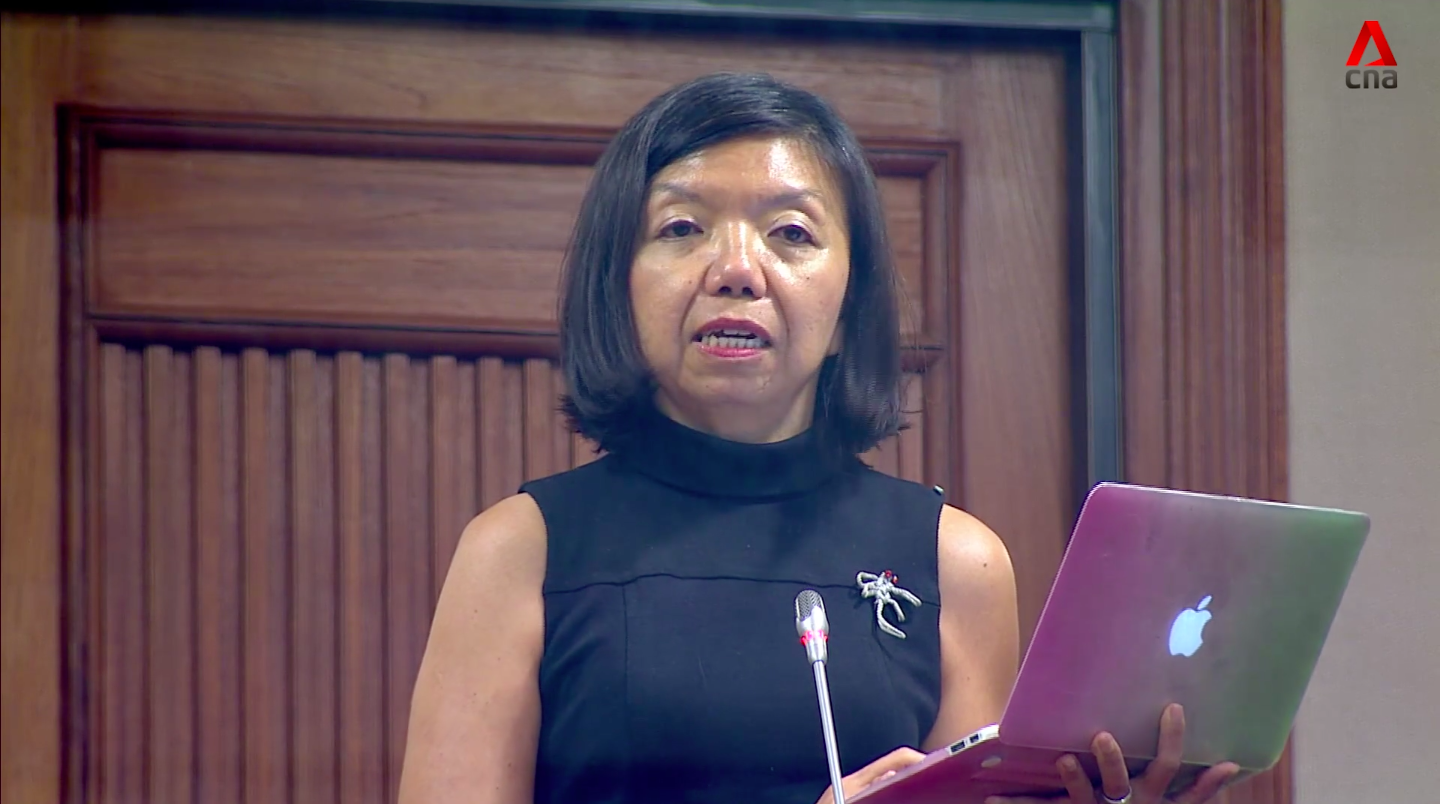

Ong speaking in Parliament. Photo via CNA.

Ong speaking in Parliament. Photo via CNA.

Supported by "angels"

As there were sittings where Ong spoke on up to four separate bills, she emphasised that her many Parliamentary Questions and speeches would not have been possible without a group she affectionately called her "legislative angels", in place of the usual term, "legislative assistants".

These "angels" consisted of 38 young people from a variety of sectors who volunteered to support her.

Ong explained that she would reach out to "angels" working specifically on the topics she was addressing.

They would then help with collecting data and crafting parts of her speeches, although she would always "Anthea-ise" it.

And she also sees this as a chance for her to help the young volunteers grow as individuals:

"I feel that what I'm meant to be in this second part of my life is actually to support others to realise their potential and their purpose.

All of this is, I'm trusting the young people... So, I play the role of sort of holding the space. I see as that role of me developing, you know, this next generation of leaders — both community as well as social sector leaders."

The most memorable moment for her in Parliament was giving a speech on youth activism that was almost completely crafted by the young volunteers:

"And so, instead of filtering their voices out with mine — my words and my tonality, all of that — I kept it almost as verbatim as I could.

And it was like I was actually not Anthea, but I was them, and bringing them into Parliament with me, and having them be heard in the highest hall of the land, and giving them, truly, a sense of being heard of having a place in this country."

Navigating controversial topics and dissent

But of course, being its NMP also came with its fair share of challenges.

One such challenge has been figuring out how to address controversial topics, although it got easier as time passed.

One controversy involved the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation (POFMA) Bill, for which Ong — together with Theseira and NMP Irene Quay — submitted four amendments.

"That was difficult in the sense that you are dealing with having to be intellectually so switched on and so sharp and incisive, because we had to draft an amendment ourselves, and we're not lawyers."

However, as time passed in Parliament, Ong realised that she was becoming more comfortable with talking about controversial issues:

"After POFMA, I kind of feel like this is something that I am getting more familiar with."

Ong said that she still feels less-than-comfortable with the feeling that "everyone's watching", heightened by the fact that she would often find herself "not toeing the same line as everyone else".

However, she has gotten more familiar with the feeling.

Ong saw it as her responsibility as a parliamentarian to raise these issues, and referenced minister Grace Fu's comments about how Parliament must go on through Covid-19, since Parliament holds the government to account:

"I don't see the role of parliamentarian as just to agree for agreeing's sake. If our role is to hold the government to account and to challenge the government, then we need to ask questions.

And some of those questions might be uncomfortable, some of those questions might be more comfortable, but that's our role. And that's what I think, you know, I was trying to do."

Open to different views, but won't entertain "haters"

Ong also shared about how she deals — or doesn't deal — with online comments and criticism.

For example, she received quite a bit of criticism for her question, which was answered by manpower minister Josephine Teo, on whether the government will consider issuing an apology to migrant workers.

One thing that she generally doesn't do, she said, was read the comments on news about her, as there will always be "haters":

"To say that it doesn't affect me, that's just lying. But does it affect me in a way that just cripples me or paralyses me? No, it doesn't...

... I'm not looking for votes. I'm not trying to be a celebrity. I definitely, right now, know I'm loved enough by the people who matter to me that I'm not looking for more love."

She emphasised that she is open to discussions with those who hold different views, as this makes our society more colourful, richer, and more informed.

However, she will never entertain "haters" or "smearers".

And when Ong encountered nasty comments, or felt fearful, she reminded herself about why she was doing it: "To be able to sort of speak truth to power but also to choose courage over comfort", she said.

Ong felt that speaking up on controversial issues would be a responsibility she owed, which she needed to fulfil.

"But more importantly, there's also all those voices and all the people who I know who have come forward, who have entrusted their issues and their voices with me."

Reflecting on her impact and time as an NMP

When asked about her feelings about the past 21 months of her NMP term, Ong said that it was a "privilege" and an "honour":

"It's such an opportunity of a lifetime to serve this way. What a privilege to be able to serve this way, in the country you love, with the people you love. It's really a privilege."

She also has learned a lot from the experience:

"It's been [so] phenomenal in terms of learnings. It's been so much personal growth.

I think being an NMP has tested me even more in my own practice of staying in truth, in integrity, and in humility. So it's not always been easy but there's been so much personal growth.

She also "tried [her] very best to spread the love" by sharing her NMP platform with many different community groups.

Ong spreading the love, via sign language. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Ong spreading the love, via sign language. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

While Ong acknowledged critiques of her work being too idealistic, she saw it differently:

"It doesn't come from a place of idealism at all, because I've come from 30 years in the business world, so I will tell you that I'm definitely not... at least, not a career idealist, lah.

But I do love this country. I love the people. and I think that when Tommy Koh talked about the critical lovers and the loving critics, I resonated with that. Because being a critic comes from so much love.

And that love doesn't mean that I don't recognise what's good in where we are — you know, all the good in the government and all the good in in our system and all the good in our society, in life."

What's next for Ong?

This chapter in Ong's life has ended with the election of the 14th session of Parliament.

But in terms of her work, nothing will really change — she plans to stay involved in many different projects in order to "continue to hold space and give support to others to realise their potential and their purpose".

Her goal of creating a more "human-centred" society remains:

"It's still really the same journey, this journey of being able to serve and bring about social change in a way that we can become a better society and country.

I definitely want Singapore to be a well-being economy, and a truly inclusive society, so I'll still be working on that on the ground in different roles and capacities."

And while she does that, Ong said that she'll keep her eyes peeled for the next opportunity:

"Just like I didn't expect this, I'm very sure that there will be surprises, and I will love the surprises, and I will then, again, show up for it completely and wholeheartedly.

And then, we'll see where that leads us!"

Ong is looking forward to seeing what her next adventure may be. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Ong is looking forward to seeing what her next adventure may be. Photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top photo courtesy of Anthea Ong.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.