SNIPPET: Prior to the advent of air travel during British rule and early years of independence, Muslims in Singapore and Malaysia would travel to Saudi Arabia by ship for the Hajj, a journey which took many days.

The journey would begin in Singapore before Ramadan had started, which meant that the fasting month would be spent mostly on the ship and in Mecca.

We reproduce an excerpt from Kapal Haji: Singapore and the Hajj Journey, about the experience of travelling on the ship, meeting pilgrims from other countries, and the variety of food that people would bring onto the ship.

Kapal Haji: Singapore and the Hajj Journey, which is written by Anthony Green and Mohd Raman Daud, is published by World Scientific.

You can get a copy here.

A hajj package by ship in 1973 cost about S$2,000

When Aisha Angullia sailed on the Malaysia Kita in 1973 the hajj package cost S$2,000 and was organised by the well-known company of the late Hajjah Maimunah in Singapore. That company’s connections between Southeast Asia and Saudi Arabia were well established:

Our Shaykh in Singapore was Hjh Maimunah but when we reached Mecca our Shaykh was Nafisa Nawawi. Her husband was Hj Mat Top, a Malay man, living in Mekkah.

In the Hejaz they would meet many long-term Meccan residents who had originated from Southeast Asia:

They speak Arabic very well: all the Indonesian people who are there, the Pattani people, the Thailand people who are there ... but they cannot speak their own language. The Malay is horrible. When they speak their language it’s so broken.

These meetings were like a small link with the past. Going back to the seventeenth century and earlier there has been a presence in Mecca of numbers of what came to be called “Jawah” or “Makkawi” – those who originated from the Southeast Asian lands of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula.

From the countless thousands who travelled over the centuries – first as small numbers of individuals and, in time, as part of larger groups – there were those who stayed on to study and to live: the “Jawi Meccan” connection.

One young pilgrim recounts how she attended a course before embarking on the journey

In Aisha’s case, two things at least stood out for this hajj journey. The first was her age when she formed her intention to travel. Most of those travelling for hajj were old people, “the youngsters a few only.”

Aisha was 25, going on 26 when she went but she’d already made up her mind to go when she was still at school in Secondary Four – at the age of around 15 or 16.

I’m thinking, when people go haji it’s a lot of money. Oh God, when are you going? When I get a little bit of money I keep, keep, keep. When it’s prayer time I said to my mother, I want to go to hajj.

Her desires weren’t shared by her adopted sister, Aisah Ibrahim, but intentions can be quietly contagious. (Her name was also “Aisha” but birth certificates could render different spellings).

Aisha Angullia was the one who “drove” the journey at first:

I said, come, we had no money but we learn first. I said to her that, at the moment we are still strong but we are handicapped. In future, in time, we did not know. Our energy is limited. That’s the main point and we prayed hard.

So they began attending a two-year course – a kursus haji – in a small madrasah in a road that’s now disappeared, called Jalan Labu.

Source: World Scientific. The kursus haji (hajj course); Aisah Ibrahim (centre) and Aisha Angullia (right) in the second row.

Source: World Scientific. The kursus haji (hajj course); Aisah Ibrahim (centre) and Aisha Angullia (right) in the second row.

Their teacher, their ustaz, was Ust Osman Jantan, a man who had also served as a guru kapal, and at first Aisah Ibrahim “just followed.”

I don’t have any intention to go. She said, “Come follow me.” I said, “I’m not going hajji,” but she said, “Never mind, just follow. One day who knows?”

One year into the course, and somewhat like the change in Maamor bin Sutan Nordin, those feelings altered and she too wanted to perform the hajj.

A range of people, including those with disabilities

But a second issue stood out – the handicap that Aisha had spoken of. Both of them had had polio when younger.

The doctor always told me, “You’re handicapped people, your energy is like 60-year old people.” And I’m thinking Oh God; I’m always thinking God will be helping us. But when we went there, there were people worse than us – without legs; without hands; with one leg; with no legs. But the men can mengaji, they can read the Qur’an. I made tawaf with one stick. She got callipers plus crutches. I’m without callipers so I always say, Alhamdulillah. It’s only for the sa’i I take a wheelchair.

The realisation came that the hajj brings together an extraordinary range of people, and their own physical condition would work in unexpected ways while they were there. Aisah Ibrahim used crutches and was wearing black most of the time.

Waiting for her sister she would fall asleep in a corner of the mosque and it seemed to prompt certain responses in those who passed by.

I have two crutches; I lie down; I would wait in one corner for my friend to come out from the mosque but when I wake up there’s a lot of money. And I asked the Shaykh, Mat Top, what I should do with this, he said, “Never mind, if you don’t want you just give to other people."

If the cost of the hajj had seemed a real obstacle this was overcome in the second year into the hajj course when Aisha’s father asked where they were going.

I said, “I go kursus haji.” “You want to go to haji?” he asked. I said, “I want but I’ve got no money.” “If you really want, I give,” so my father gave.

Met fellow pilgrims who shared her name

Boarding the ship brought a new challenge.

Their brother had taken their luggage down to the lower decks where they were booked to sleep and he realised that they’d have to climb up to an upper deck to eat so he was firm: “You can’t stay in this place. You are both handicapped.”

Negotiations followed with a very good friend on board, Mr Awab.

The “A” class cabins were all for the Malaysian staff from Tabung Haji, he was told, but one room was available.

After Port Klang the medical staff from Malaysia came on board the ship and a nurse from Penang joined them in their room. Her name?

Aisha also! Three Aishas in the room. We called her sister because she’s a nurse.

And in Saudi Arabia there’d be “another Aisha” when they met and made friends with a lady from South Africa, a lady they kept in touch with for some time afterwards.

Meeting others from different parts of the world, interacting, sharing experiences, seems a strong element in their memory of this journey.

We meet a lot of people in the ship and in the mosque; we share together. This ship carried jemaah [community] from Singapore and Malaysia. So we met a lot of Malaysians there.

That sharing included knowledge of the hajj rituals themselves:

Some of them they don’t know anything. They see us sitting down reading so they come and join us, because we took a two-year course. They didn’t know the proper way to do some things. They know about tawaf but some don’t take the course. When they know us they like us both because we’re friendly to them; because we cannot keep quiet.

One more advantage the sisters had was linguistic.

Speaking Malay and English was a start but the Angullia family name originates in the north-west of India and the extended family has trading links around the Indian Ocean so Urdu and Hindi were part of the capabilities and with a father from Mauritius, Aisha was able to speak a bit of Creole.

One lesson they had been taught: Don't judge what you see

Aside from the teaching of rituals the hajj course had laid stress on attitude. They’d been reminded that, on the hajj they would see all kinds of things.

Our ustaz always reminded us, don’t say anything about this is strange; don’t think you’re better than others or laugh at them; you can always help. If anyone is struggling that all belongs to what they do before they go. We cannot laugh at them; cannot say “you have a lot of sin.” I think if you don’t go to the kursus you can always get lost there; maybe you cannot control your anger; you always want to be right.

These were qualities that were emphasised by the older ladies that they spoke to on the ship. “Be patient,” they were told. “They were older, so we respected them.”

Some of their fellow pilgrims on the ship were unable to read the Qur’an but Aisha Angullia’s response was to say to them,

Makcik, [Auntie] no need to read. Just say Subhannallah, Alhamdulillah, la illa ha illallah, Allahu akhbar. Allah will accept. Don’t worry. I see you all can recite this. We don’t know how our haji will be, correct. I said, it’s from the heart. If your niyah is good and your money is clean, then sure you will be ok.

And it wasn’t just an inability to read the Qur’an. There were everyday issues on board – some that you can get a feel for when looking at the “exploded” view of the ship TSMS Kuala Lumpur in chapter 7.

Bunks on the ship were labelled with pictures of fruits for the illiterate

Each bunk on the ship had a number but finding your way through the different decks to your own berth could be perplexing, especially for older village folk, probably on a ship or in such a space for the first time.

Shipping companies tackled this by painting symbols instead of writing words: in this case, buah manggis, buah durian, buah rambutan – mangoes, durians and rambutans.

You follow the picture to find your way to your berth. If you were stuck and lost, a Malay-speaking crew member would lead you around and ask, “Does anyone recognise this person?”

Habib Hassan Al-Attas, Imam of Ba’alwie mosque in Singapore experienced that, returning from Jeddah as a young man with his father in the Malaysia Kita in early 1972.

Boarding the ship, he too saw pictures of tropical fruit painted up around the ship – rambutan, mangosteen, duku and others – with arrows directing clearly where they could be found.

These were favourites and after spending many months in Saudi Arabia he was keen to make their acquaintance once again.

So, after assisting his father to his cabin, he went out and followed the arrows. He went deck to deck but all that he found were just beds full of pilgrims.

Tired and after searching for more than half an hour, he met the Chief Purser, Mr Osnain, and asked where he could get these fruits.

Osnain just laughed. “Fruits? Sorry there are no fruits! These are names of ‘kampungs.’” [like villages] With more than one thousand pilgrims on board and so many being illiterate, the familiar was the easiest way to guide them to their sleeping places.

The ship was not very comfortable in general

To add to any discomfort in finding your way around, Aisha Angullia remembered it being, “very dark, and hot” inside the ship.

Daytime they would go up on deck and rest and sleep there. Sometimes the captain would come and say it can be dangerous, you never know how the ship will move. But, Alhamdulillah, our journey was very smooth. We went during fasting month, Ramadan. From Singapore it was not yet Ramadan. We reached there in Ramadan. The whole month of Ramadan was in Mecca.

There is a gap of more than three months between Ramadan and the time of the hajj and this, too, made the journey different from modern days when the time spent on hajj is far shorter.

Pilgrims brought their own food and cuisine onto the ship

And if we trace back to the nineteenth century, and especially in the time of sail, pilgrims would likely be away on hajj for at least a year and always when people travelled from Southeast Asia they took with them supplies of food.

During our time we had to cook for ourselves. We bring our own food, our own rice in a big box; everything inside; our ingredients, our pots and pans, our masalah. We had to bring batu lesong [pestle and mortar], dried chillies, dried fish, all our ingredients, lah! But when we reached there we see everything already there. We see spices, and a lot of dried fish there. Our box was very heavy but there in Mecca one man picked it up by himself and carried it!

The makcik from Kelantan, they take ikan bilis, they make like a pickle, it looked like ulat, like worms.

They make like a salted durian and they bring that. I bring pickle; I bring salted fish, serunding [floss] – in a big tin; to eat there for the three months.

In times past when there was no food provided on board, one comment of ships’ crews was that by the time the pilgrims were ready to return home, food such as the rice that they’d brought with them from home was often riddled with weevils and unfit for consumption.

There was little or no nutritional value left in it for bodies – often, old bodies – that were exhausted after the rigours of the hajj.

Performing the hajj is a deeply emotional and spiritual experience

Whatever hardships there were on the outward journey seemed far outweighed by the joy of arrival. For the two sisters there was Mecca and the sight of the Kaaba for the first time.

When we saw the Kaaba we just can’t control our tears. It was very nice to see Arafah; when you see you can’t imagine what this place is; really meaningful for me.

Ust Hj Ali Hj Mohamed remembers the same kind of reaction; tears that cannot be explained in words.

Your inner feelings change (approaching the Kaaba), and you don’t know how but you start crying. It’s different, depending on whether you are nearer or farther away. But of course you forget everything when you see the Kaaba. The only words from you are “Labbayk Allah.” [Here I am, O Allah] – meaning here I am, to serve.

From Jeddah to Mecca and Medinah the sisters travelled in a group; something that added the pleasant experience of community into what is an individual’s undertaking.

During the three months we were together we were like a family there. It was a bit cramped where we stayed in Mecca but we never mind as long as we are together. We were in the downstairs because the stairs were so big. They all can manage up and down but we two cannot. Upstairs were Afghans.

And then, after the culmination of the hajj at Arafah where Muslims accept that the last sermon of the Prophet Muhammad was given, and in leaving Mecca and boarding the ship to leave Jeddah, the feelings were clear.

Just like the tears on arrival, they are feelings that have been echoed by thousands who have made the hajj.

Very, very sad. You don’t know where your tears come from. We always pray that one day we can come back again but we don’t know when we can. We’d stayed there three months. We know a lot of people. We meet friends from all over the world.

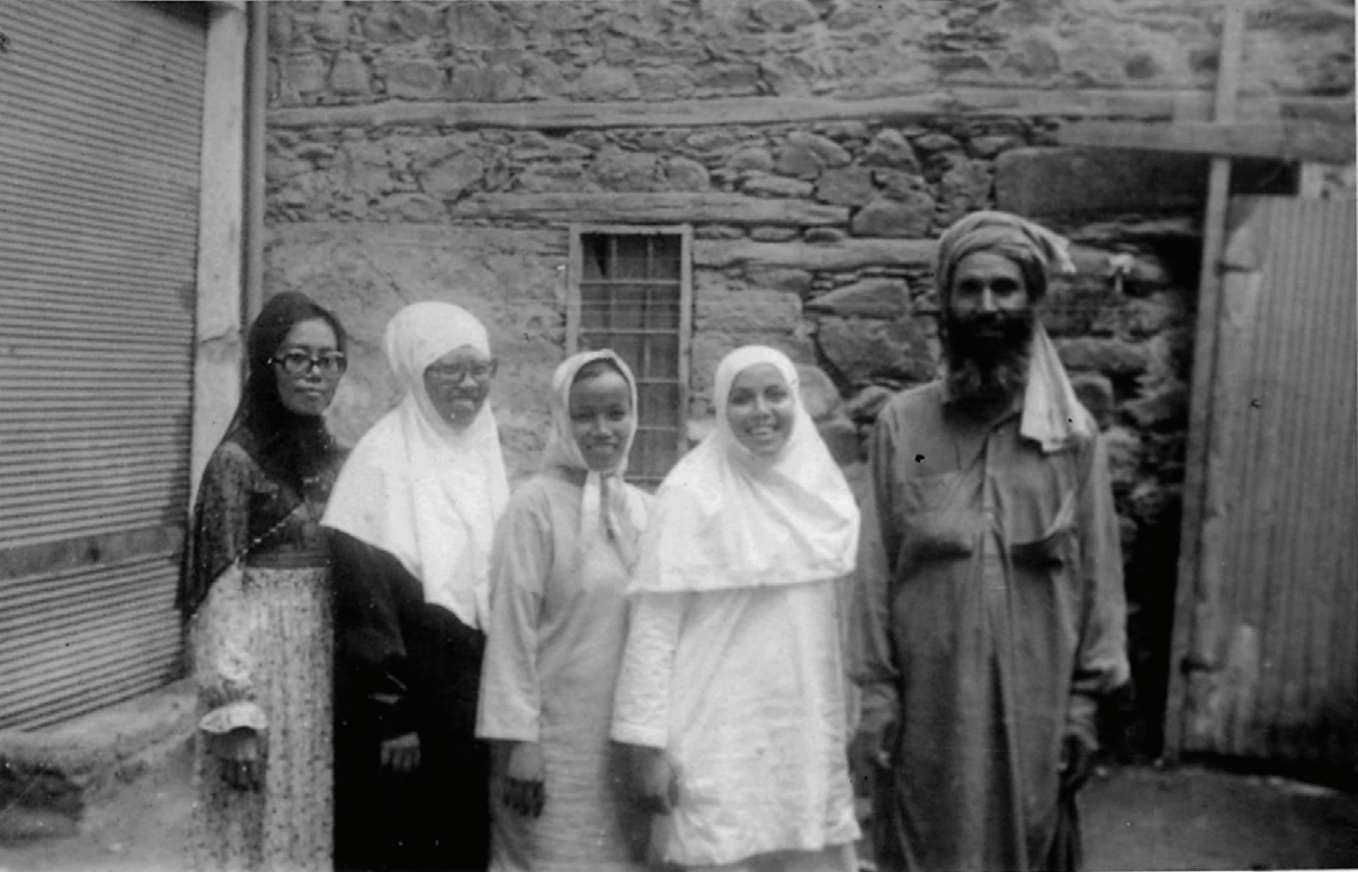

Source: World Scientific. A note in their collection of photographs says, “Photos of friendship, goodwill and fond memories. . . taken in the holy land of Mecca.”

Source: World Scientific. A note in their collection of photographs says, “Photos of friendship, goodwill and fond memories. . . taken in the holy land of Mecca.”

Top photo from World Scientific

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.