SNIPPET: Singapore served as a key transit hub for pilgrims in Southeast Asia during the days of British rule, and early years of independence. Prior to the advent of air travel, Muslims in Singapore and Malaysia would travel to Saudi Arabia by ship for the Hajj, a journey which took many days.

We reproduce an excerpt from Kapal Haji: Singapore and the Hajj Journey, about how funerals and births were conducted onboard the ship, how the non-Muslim crew and the pilgrims perceived each other, as well as how passengers could be subjected to a 14-day quarantine in the event of a disease outbreak.

Kapal Haji: Singapore and the Hajj Journey, which is written by Anthony Green and Mohd Raman Daud, is published by World Scientific.

You can get a copy here.

Prior to the compulsory provision of meals, pilgrims often fell sick from their own food

By the end of the pilgrimage many of those who had taken part were exhausted and in the days before 1929/1930, when it became compulsory to provide meals on board British ships, this was not helped by the food that they would have been eating.

In his recollection of the voyage from Jeddah to Java, Capt. J. H. Brown said that once the pilgrims had boarded and firewood had been issued, cooking began:

"The food was rice, dried fish, etc., which had been brought from Java and stored in cellars and godowns in Jeddah while the pilgrimage was underway. By this time it was pretty ripe and smelly; doubtless being the cause of dysentery which nearly always occurred with

resultant mortality."

But, he adds that, “in sickness, rarely was the ship’s surgeon called upon, not even by the elderly people.”

In addition to the surgeon, the ships carried “restoratives” for anyone who was weak, though these now seem strange, as they may well have done even then to the pilgrims.

Guinness would be given to pregnant women as well

For women in confinement before giving birth, “a bottle of Guinness was given to the mother.”

If they did drink it thinking it was medicine one wonders if they knew it was alcohol. Something more Islamically acceptable but still from a different culture appeared on the S.S. Tyndareus in the 1960s. John Spain remembers Marmite:

"The doctor was European – quite an old, senior doctor. But the main problem always coming back from the pilgrimage was Beri-beri. They’d just not eaten the right foods, and some of them were in a pretty bad state. But, as he said, two or three days on Marmite, and they regained all the strength they’d ever lost. Just to replace all the vitamin B, which they’d lost. For an old person the hajj was quite an onerous task."

Funerals were a near-daily occurrence

Captain Gwilym Owen had joined Blue Funnel as a deck boy in 1945 and was an Able Seaman on the ship Atreus in October 1948:

These pilgrims had been for several weeks in the intense heat of Saudi Arabia and most of them were elderly people, and therefore very sad to say we had a funeral almost every day. The ship was stopped at noon for the funeral, which was carried out over the stern of the ship. The ship’s carpenter had made a wooden base to lay the body on and the bosun had rigged a tackle from a small davit right over the stern of the ship with a rope rigged to one end of the wood base to tilt it so that the body would slide off into the sea after it had been lowered down to the water’s edge via the tackle.

But a sense of respect comes through in Captain Owen’s account:

One day I was the 10am to noon helmsman on the 8am to 12pm watch. When I was relieved at noon there was a funeral taking place. I left the bridge and proceeded aft to the accommodation and went to wash my hands before having lunch. I could hear some commotion on the deck above where the funeral was taking place and when I lifted my head to look through the porthole directly astern – I could see the corpse swinging around in the moderate breeze with the shroud being blown off the corpse to expose the bare feet and legs.

The rope tackle had got twisted with the moderate breeze to cause this ugly incident. One morning we had to carry a very sick pilgrim up on deck from number three hatch and tried to find a sheltered spot to lay him down on the main deck. This was about 8:30am and he died at 3:30pm that afternoon.

We carried a ship’s doctor and two or three male nurses as extra hands to look after the pilgrims. They all did their very best, but sad to say, many of the pilgrims were very sick when they boarded for their homeward passage. I remember another sad incident when the ship’s doctor was pulling large worms from the veins of the legs and feet of a pilgrim on the main deck abreast of number six hatch.

Both births and deaths on the ship also had to be tracked

The ship’s master was required to register any births or deaths that took place on a voyage.

In the case of births, the date, name (if any) of the child and the details of the parents. In the case of deaths, the date of the death, full name, age, occupation, nationality and cause of death.

Under “Burial at sea” in the Medical Guide it was stated that the captain should “Record the event in the official log book with the exact time and position of burial.”

Ralph Kennett was a CNCo master of the hajj ship, Anshun. Writing of the years 1966 to 1968 he recalled that,

... we had an average of six deaths outward and six deaths home and since two voyages were needed each Hadj season, this added up to 24 burials at sea per Hadj. Death at sea requires the Master to fill in 34 forms and all in all prevention is preferable, and we all worked toward this end.

Newborn babies could be named after the ships themselves

And, too, there were births. And on occasions – J.H. Brown wrote that this was “invariably” – the child might end up with a name unusual in the Malay world with the ship’s name included in their own. On the ship Tyndareus in 1951,

There were ten deaths during the 18-days voyage home. But there was an addition to the group, when, 14 days ago, Mohamed Tyndareus was born at sea. He was named after the ship.

And in June 1966, on the Anshun 1,127 pilgrims arrived: for Penang, Port Swettenham, Singapore, Kuching, Labuan and Jesselton.

That number included a baby. “He was named Abdullah Anshun, after the ship. His parents are from Langgar, Kedah.”

Dutch ship records indicate that for the “place of birth” the ship’s captain would enter the coordinates of latitude and longitude: we all must be born somewhere!

Whether those ship names stuck as personal names once these infant pilgrims were home is another interesting question.

Some of the ruling colonial powers saw the pilgrims through bigoted lens

Earlier chapters cited some dismissive, even contemptuous, nineteenth-century references to hajj pilgrims and there were enough people in colonial times who often saw little dignity in the faith of those they ruled over:

Texts taken from several royal libraries that were taken as trophies of war, from Selangor (1784), Yogyakarta (1812), Bone (1814), and Palembang (1812 and 1821)... failed to convince some Europeans of the commitment of Southeast Asia’s Muslims to their faith.

When the Indian Passenger Act 2 of 1860, was passed it was said to be,

... with the laudable design of preventing the overcrowding of passenger ships, by emigrant coolies in search of employment, and by fanatic Hadjees in search of Mahomet’s paradise.

[emphasis added]

And when the abandonment of the Alsagoff ship Jeddah was first reported the Singapore newspaper identified that it carried “planks and 950 pilgrims,” the wood seeming to take priority in importance over the people.

But the non-Muslim crew of the ship was generally respectful

But in many twentieth century accounts or recollections of those non-Muslim crew members who interacted with them or at least observed them, a different tone comes across.

A report from 1936 was of a young man who had sailed as “an apprentice” – a midshipman. Looking back on that experience he wrote:

I was young then, and the carriage of pilgrims at certain times of the year was just part of the job I had chosen to do, but with hindsight I realise I was very fortunate to have had the experience of another culture, even though I was only an observer.

Capt. Paddy Gorman was master of the Kuala Lumpur in the 1960s.

He was recorded as having carried 40,000 Malaysian hajj pilgrims over five years and in the 1969 “Merdeka Honours” he was awarded the Johan Setia Makhota Award (JSM), together with a standing invitation from Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Tengku Abdul Rahman, to stay in his Penang house “anytime Captain and Mrs. Gorman visit the island.”

Capt. Gorman’s comment was that, “The pilgrims are very gentle people. They have never given the crew any trouble. They spend most of their time praying, or getting to know one another.”

It’s a response well remembered by Darrell Daish. He sailed with Paddy Gorman and recalls him looking at the pilgrims, shaking his head slowly, and saying, “Ah, they’re lovely people, Darrell, lovely people.”

If a disease broke out in Saudi Arabia, pilgrims had to be quarantined for 14 days

There were times when that long hajj journey did not end with the return of the passengers to their home port.

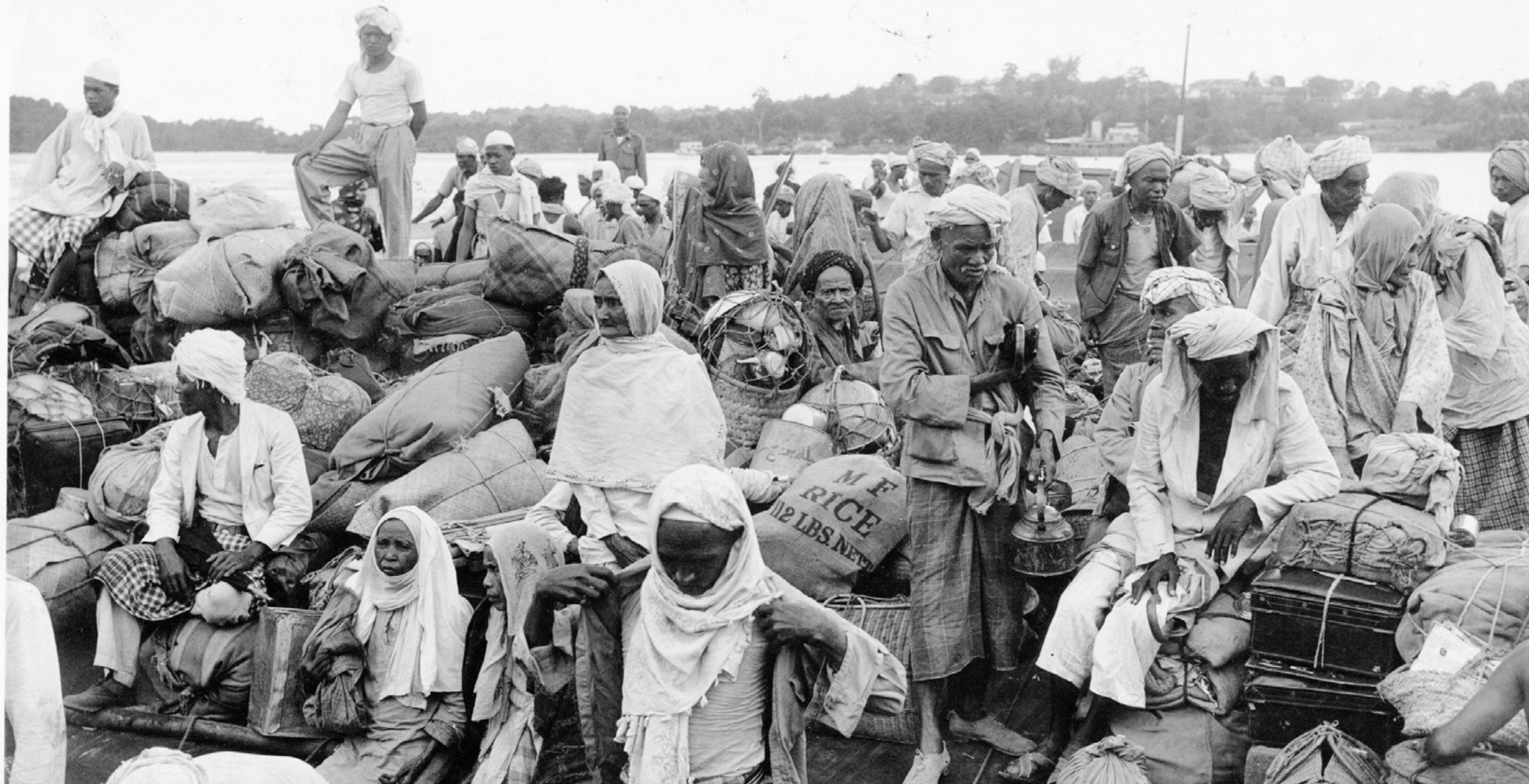

In late 1949 there was another outbreak of smallpox in Saudi Arabia and in early December of that year, a seven-year-old boy on the Tyndareus was found to have the disease.

There were 2,012 other passengers on board and, aside from a few fortunate souls who were travelling first class, 868 of them who might have expected to be disembarking at Penang had to continue straight past – one can imagine, within sight of waiting families and friends – down the Straits of Malacca to St John’s Island, just off Singapore.

Here they were quarantined for two weeks before they could finally board specially chartered trains at Tanjong Pagar Station to travel home.

Whatever their inner feelings, the photograph suggests it was a further test of stoic patience and some tiredness.

Source: World Scientific. Pilgrims disembarking at the Singapore Harbour Board wharves on 23 Dec 1949 from their two weeks’ quarantine on St John’s Island, ready to board special trains to take them back to “Johore and Northern Malaya.”

Source: World Scientific. Pilgrims disembarking at the Singapore Harbour Board wharves on 23 Dec 1949 from their two weeks’ quarantine on St John’s Island, ready to board special trains to take them back to “Johore and Northern Malaya.”

Those who returned from the Hajj had a new title and respect

But those who returned home could now assume the title Haji or Hajjah and the men could wear the white songkok, or skull cap, to denote their status, especially at “any other occasion that required [someone] to assume [their] religious persona.”

In Southeast Asia this was always treated as a special title, “a term that was important [to an individual] and his neighbours,” and even if, at times, the returning hajji was not specially versed in the teachings of the faith, they might assume a new role in their village community.

Roff’s observations in Malay villages were that,

... imams led prayers in mosques and village suraus, khatibs delivered Fridays khutbahs, returned hajjis gave elementary instruction to children in Qur’an recitation and the elements of the faith, usually in their own homes or the suraus.

In these cases it meant the continuation of a pattern of modest learning within a society shaped by respect for traditional, almost feudal structures.

It was towards the end of the nineteenth century that many of that increasing number of those who had stayed and studied in the Middle East would bring back reformist ideas of how the faith of Islam should be understood and taught – the kaum muda that we have spoken of.

In Indonesia that movement argued against the syncretic nature of the practice of Islam. These

arguments were discomforting to established understandings and established societal relationships and order.

In the Malay Peninsula – less so in urbanised Singapore – the kaum tua, the older group, might feel threatened by any number of seemingly trivial issues.

Top image collage from World Scientific and Jnzl's Photos via Flickr

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.