As the Covid-19 pandemic in Singapore continues to rage on, our thoughts and support are with those on the frontlines fighting the outbreak.

Doctors and nurses have gotten much recognition for their important work in battling this global health crisis, and rightfully so.

However, one group of people, whose work is often less visible yet incredibly integral to the frontline response, has been more-or-less overlooked: the housekeeping staff at our hospitals.

Housekeeping staff are at the very front of the frontlines — they are frequently in contact with surfaces contaminated by suspected and confirmed Covid-19 patients in order to ensure they are properly disinfected, for the protection of other patients and healthcare staff.

To get a closer look into the lives of the important people keeping our doctors and nurses safe, I spoke with John Christopher Vega and Thinzar Aung, two of the housekeeping staff employed by ISS Facility Services who are working at the National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID), to find out more about their jobs, their motivations, and their fears.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Housekeeping staff at NCID

Vega and Thinzar, both 26, have been working in Singapore for almost two years and six years, respectively.

Vega hails from Tuguegarao City in the Philippines, a city of only 153,502 people. Thinzar, on the other hand, is from Yangon, the capital city of Myanmar.

They both received university educations in their home countries — Thinzar in computer science and Vega in business administration — but came to Singapore in search of a better life and higher wages.

Here, Vega works as a housekeeping operative in the NCID screening centre. He has been working in the NCID building for the past nine months, previously doing the daily cleaning in the wards until he was transferred to the screening centre for Covid-19 when the outbreak started earlier this year.

John Christopher Vega, 26. Photo by Jane Zhang.

John Christopher Vega, 26. Photo by Jane Zhang.

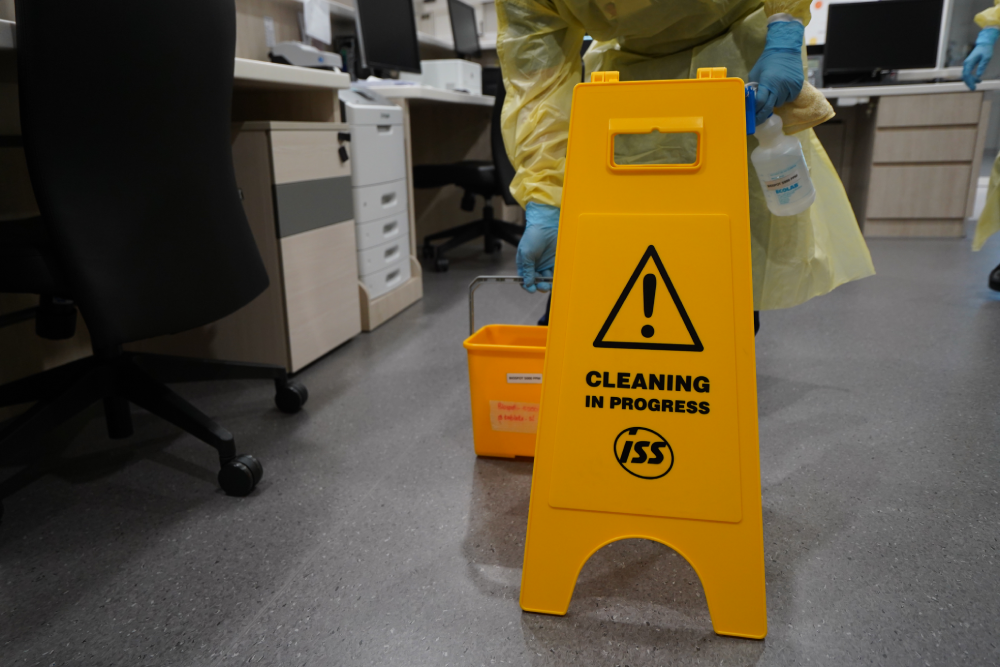

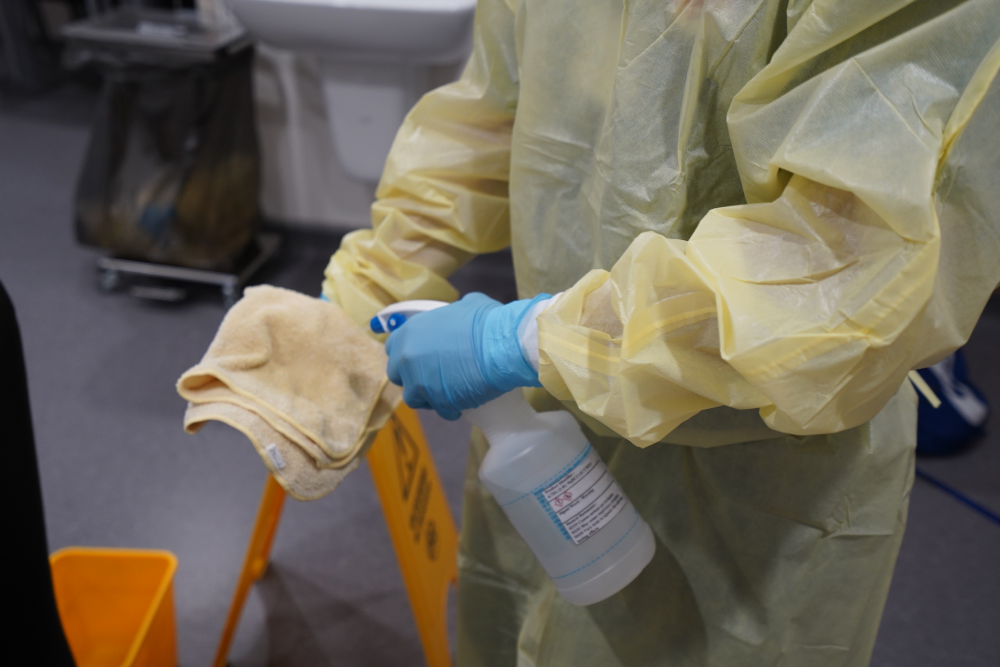

His role in the screening centre includes constantly wiping down the tables and chairs where suspected cases sit, cleaning the bathrooms after each use, sweeping and mopping the floors, and wiping down the high-touch areas of the centre five times a day.

"And of course the counter. We never forget the counter", Vega chuckles, reiterating the importance of wiping down one of the highest-touch areas in the NCID premises.

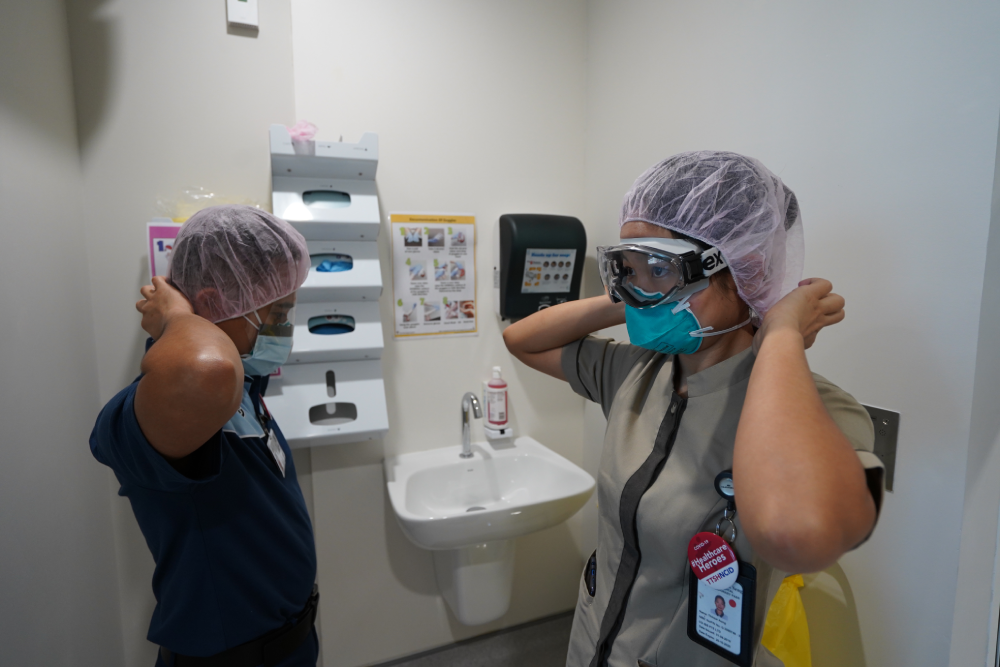

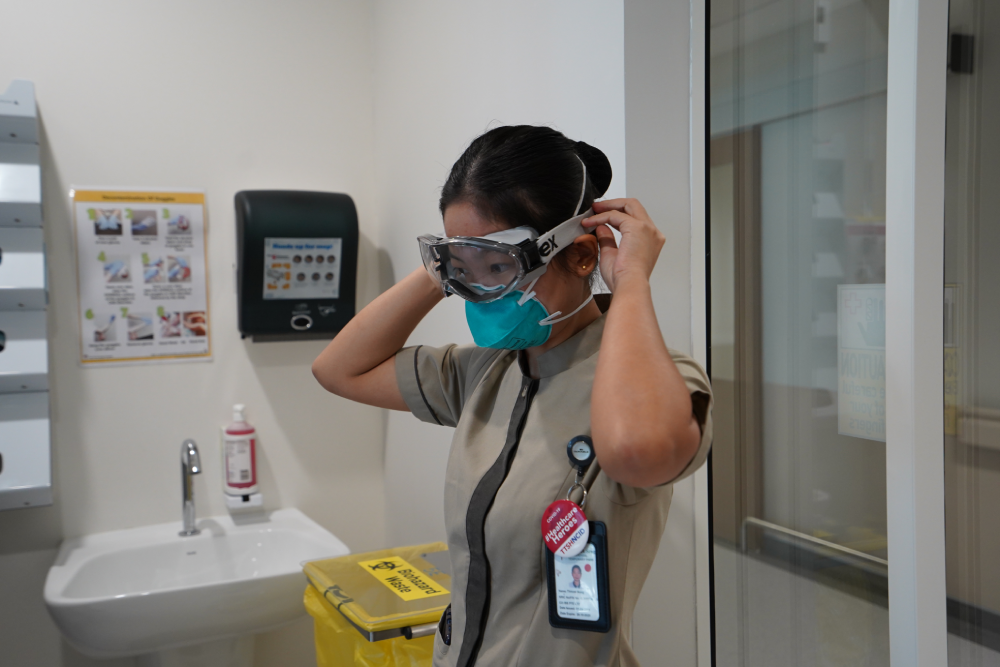

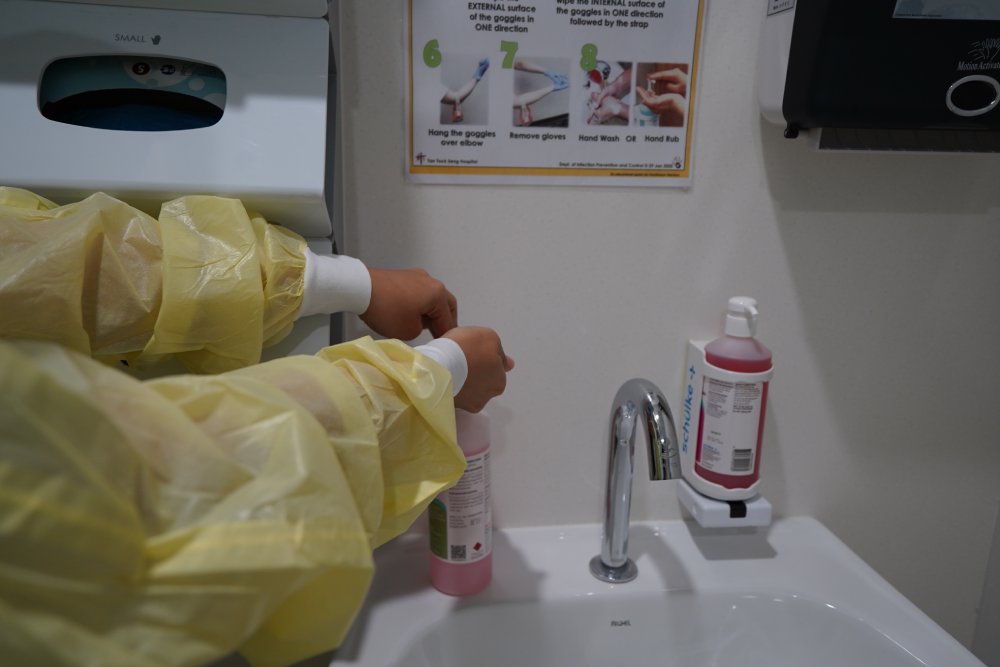

His constant close contact with suspected (and possibly later-to-be-confirmed) cases requires him to wear full personal protective equipment (PPE) at all times.

The full PPE includes eye protection such as goggles, a face shield or a mask with a visor, an N95 mask, a long-sleeved plastic gown, gloves made of synthetic rubber, and a shower cap.

Thinzar, on the other hand, is a housekeeping supervisor. In her role, she manages 100 staff members, one of whom is Vega.

Her responsibilities include conducting morning briefings, overseeing the housekeeping roster, and deploying staff to the different areas of the centre, such as the wards where Covid-19 patients are held and the screening centre.

Thinzar Aung, also 26. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Thinzar Aung, also 26. Photo by Jane Zhang.

She also ensures that the housekeeping protocol and strict standard operating procedures are followed, according to the hospital’s infection control standards.

This includes making sure that the chemicals the staff use to clean are diluted and used accurately and that waste is disposed in the correct way.

These measures are also important for ensuring that her staff are safe and protected from contamination as they carry out their work.

Vega and Thinzar come into close contact with Covid-19 cases but both express that they do not feel afraid because of the extensive training (for example in wearing PPE) they go through to protect themselves.

"The first time, really, we think like that. But, we are trained in this. We are trained already in this, so we are ready for it", Vega tells me.

Thinzar adds on, "We always standby for the outbreak. In any time, outbreak may happen. That's why we always conduct training".

Longer hours, sometimes can't take breaks

Both Vega and Thinzar work unimaginably (to me, at least) long hours, six days per week and the hours have gotten especially long now that the intensity of the Covid-19 situation has risen.

Thinzar explains that prior to the virus outbreak, her role had three shifts: 7am to 3pm, 1pm to 9pm, and an overnight shift from 7pm to 7am.

Now, however, the two daytime shifts have been combined, forming only two shifts: a 14-hour shift from 7am to 9pm, and a 12-hour overnight shift from 7pm to 7am.

While Vega’s shifts haven’t necessarily gotten longer, compared to before the outbreak, he does spend more of his 12-hour workday (from 7am to 7pm) on his feet cleaning all of the different areas while donning the full PPE, which also makes his work all the more difficult.

And while they are each given a one-hour break for lunch and for dinner, they sometimes have to forgo them depending on the busyness of the day and patients' needs.

"But now, sometimes we don't have enough rest time. We just... eat also sometimes cannot eat", Thinzar shares. "Sometimes breakfast also don't have, lunch also don't have. Only in the dinner, altogether eat".

"Even sometimes cannot pass urine also!", she adds, laughing.

"It’s our duty and our responsibility"

Given the difficult manual work, long hours, and being far away from home, I ask Vega and Thinzar what keeps them going.

"It’s tiring, but it’s our duty and our responsibility, so we can do it", says Thinzar.

“Sometimes it’s tiring, but when we think about our family and all our loved one and all the patient, it really formed a big part of the motivation. Just thinking about them give us the energy to fight this virus."

Vega adds, "I just always think that it's for the community. We can, in our own way, we can help."

In addition, Thinzar says that the appreciation they receive from their superiors and patients through "appreciation goodies" and words of encouragement makes them very proud to be part of the housekeeping team.

They are also motivated when they see that their work is integral to keeping the hospital running and keeping everyone safe.

"We provide the patient and the staff the clean environment, safe environment. Seeing the patient, because of us, they can stay safe and clean, it's really help motivate us", Thinzar tells me.

Vega feels similarly, keeping in mind that the job is bigger than just himself:

"Aside from, it’s my job, I’m just thinking that in this way I can help. This is not only for us, it's also for the patient, the nurses, and the doctors here, keeping the area clean. And then all of us inside the same."

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Not just an "easy cleaning job"

When I ask Thinzar and Vega if they feel that the public sometimes forgets that housekeeping staff like themselves are also working on the frontlines, Vega answers, with some hesitation:

"I really observe that, like, sometimes just the doctors and nurses are being… are being recognised."

"But… how do I say...?" he trails off.

Thinzar jumps in with her thoughts, pointing out that the appreciation goodies and thank-you cards are proof that people do recognise housekeeping staff as frontline workers.

"So I think everybody in Singapore, they recognise our housekeeping also as a frontline".

However, she does point out that some people may have misperceptions about the scope of their jobs, and think that it’s "just an easy cleaning job":

"Some people may not know how our housekeeping job is important. Because when they hear housekeeping, they think we are just only collect rubbish, washing toilet — they may think like that.

Actually, our job is also very important because we have to make sure to provide the safe and clean environment for all the patient and staff around here. We have to make sure that this patient room is 100 per cent clear for the next patient to come in safely."

Vega agrees, adding:

"They might think that we only do wiping and mopping floors, but they don't know that we are following some infection control procedures, standard operating procedures.

We are doing the terminal cleanings (an intense disinfection procedure), the high-level cleaning."

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Another thing that the public might not be as aware of, says Thinzar, is that the housekeeping staff at NCID also have to wear the PPE during their course of work.

Both gamely agree to demonstrate the donning of their PPE, a process that usually takes about three to five minutes:

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Vega and Thinzar in their full PPE. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Vega and Thinzar in their full PPE. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Instructions for putting on PPE. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Instructions for putting on PPE. Photo by Jane Zhang.

Wearing PPE for long hours can be very uncomfortable and it shows.

As Thinzar and Vega take off their PPE after wearing it for a mere 15 minutes, I see that their masks had already produced visible marks on their faces.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

And similar to the discrimination that some nurses and other healthcare professionals have faced in Singapore, Thinzar also has an experience to share.

She tells me that at the beginning of March, she moved into a new flat, as the lease of her old one had finished.

However, one day after moving in, the owners of the flat found out that she is working at Tan Tock Seng Hospital and NCID.

Even though they didn't live in the same flat with her, the owners demanded that she move out, for fear of being infected, says Thinzar.

"So within one day, I have to move house. Then I don’t know where to get the new house, it’s only one day. Luckily, my contract manager, he helped me out. He asked me to stay at the hostel for a while. So now currently I stay at the company hostel."

That was a month back and Thinzar is still in the process of looking for a place to stay.

Unfortunately, it is still a difficult process her. Many landlords are unwilling to rent her a room in their flats because of their misdirected fears.

Vega has been luckier, he says, and has not faced such backlash from those around him, as he is living with family members in Singapore who also work in the healthcare industry.

Don't want families to worry about them

Yet, despite the hardships and the long hours that come along with their work, neither Vega nor Thinzar have told their families back home that they work directly with Covid-19 patients, for fear of causing them anxiety.

Vega usually speaks to his family once a week for about an hour, but sometimes isn’t able to because the internet connection back home is quite slow.

Thinzar, on the other hand, calls her family two or three times a week, usually spending between half an hour to an hour on the phone with them.

Both their families are aware that they work at NCID. However, they do not know that Vega and Thinzar are in contact with Covid-19 cases.

Thinzar’s family is worried for her, she says:

"They ask so many question — how have I been here? Is it so many patient? Is it safe for me? They ask so many question.

I say, here in Singapore, here facility are different from our country, so no need to worry and everything is safe here."

"We don’t want our family worry for us, that’s why we didn’t talk [tell them]", she explains.

Instead, she says, she gives them advice on how to stay safe back home in Myanmar, where the healthcare system is not as robust as Singapore’s:

"I tell my parents to stay at home, drink more water, watch hands frequently. I teach them seven-step handwashing, how to wash hand also from the video call".

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Photo by Jane Zhang.

Vega also tries to encourage his family back home to be careful, as the province that he is from, Cayagon Valley, had reported its first case (and as of Apr. 1, the number of cases had risen to 20):

"It’s really crazy there [in the Philippines]. And then, they really don't have the facilities like here. That's why when I call up home, I just have them stay at home, don’t go out. You have enough food there, you just stay there."

I ask them if they might consider telling their families about the realities of their work one day, once the Covid-19 outbreak has passed and they are no longer working so closely with infected patients.

"Maybe I can, I can tell them already, after the outbreak. I will be proud for myself when I tell them, 'I've been there'", says Vega.

By then, he adds, "I think they will not be scared. I think they will be proud of me."

Thinzar shares similar thoughts:

"They may worry. First, when I talk, they may worry, but in the end, I will explain how we fight this Covid-19 — not only our housekeeping team, all the nurses and the doctors, all these people around us — how we fight this virus.

And I'm sure my parents, they will be proud for us."

And sitting here across from these two individuals who are just about my age, who left their homes in search of better jobs overseas, and who are now working more than 12 hours a day at the frontlines of this crisis in Singapore, I can say with certainty that I am sure their families will be proud too.

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or making the world a better place in their own small way, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top photos by Jane Zhang. Quotes have been edited for clarity.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.