Tucked away in a corner of the second floor of Middle Road’s Fortune Centre is Kappou Japanese Sushi Tapas Bar.

Despite its unassuming surroundings — neighboured by various vegetarian eateries and sharing a thin partition with a Korean restaurant — going through a glass door brings you into a tiny world of high-quality authentic Japanese cuisine.

The restaurant’s interior is sparse. 12 seats face the kitchen, separated only by a counter, giving diners front row seats to the preparation of their food.

Choo blowtorches a piece of fish, charring it, while allowing the fat to drip down into a dish. Photo by Nigel Chua.

Choo blowtorches a piece of fish, charring it, while allowing the fat to drip down into a dish. Photo by Nigel Chua.

Spectating would be an appropriate analogy for anyone who eats at the restaurant. On the other side of the counter, 26-year-old owner and chef Aeron Choo dazzles her customers with both her cooking and her showmanship.

"Kappou", the first word in the restaurant’s name, literally translates from Japanese to mean “to cut and to cook”. It is a style of omakase dining, where the chef decides the various courses and cooks the food in front of his or her diners.

According to the Michelin Guide, this style of dining emphasises the close proximity between customer and chef. That’s exactly what you’ll get at Kappou Japanese Sushi Tapas Bar, where dining is very much an interactive and often fun experience.

One course that Choo serves us involves a fist bump, the plating of caviar on the back of our hands, a spritz of “caviar perfume”, and then an encouragement to lap it up dog-style.

Choo dishes out a serving of caviar onto a fist. Photo by Nigel Chua.

Choo dishes out a serving of caviar onto a fist. Photo by Nigel Chua.

However, the fun Choo seems to have serving up Japanese cuisine wouldn’t be possible without the elbow grease and hard work she put in over the last decade.

But all that toil has earned her the unofficial accolade of Singapore’s first female chef-owner to open a Kappou-style restaurant in 2016, which continues to enjoy brisk business four years on.

“I really feel very lucky that we are still full every day,” she tells us. “I believe it's the consistency of effort and hard work that has been put in every single day.”

Without a doubt — as a female chef in a male-dominated scene, Choo has had to put in twice as much effort and hard work just to succeed.

It’s traditional thinking — that females should stay on the diners’ side of sushi counters — which relies heavily on dated stereotypes as justification and little else, really, Choo explains.

Take for example, she says, the issue of women on their periods.

“In the old school way, the consistency (of the food is down to) the chef. Therefore the prejudice of like ‘oh woman, when you’re having your period you cannot taste well.’”

Besides her, there are other females who are doing well as sushi chefs, she counters.

“I mean, as a man you also can have a bad day right? So does that mean that if you have a bad day, you’re gonna have bad taste buds? That’s not professional.”

Choo is also entirely unconvinced by another gender stereotype: hand warmth.

“They say that [women] have warmer hands. Well, I do hold some guys’ hands and they're quite warm also,” she chuckles incredulously, dismissing it as “not legit”.

The obvious remedy for this, she points out, is something already done by chefs, whether they are male or female: dipping hands in ice water before making sushi.

“I always make sure that there’s ice in the bowl,” she says dryly.

Choo shapes rice for sushi. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Choo shapes rice for sushi. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Choo dishes out these lines with playful, almost teasing confidence and snark.

And after hearing her story, we are convinced she is completely entitled to it, having struggled and succeeded as a young woman in a man’s world, over the past 12 years.

Falling in love with Japanese culture... and breaking it down

Choo’s journey began when she started developing a love for Japanese culture, through J-rock and sushi, at the tender age of nine.

Just five years later, she started working as a dishwasher. From here, she would go on to work her way into the kitchens of various “true” Japanese restaurants and eateries owned and operated by Japanese owners and chefs.

After all, her ultimate goal was to be able to open an omakase restaurant, so as to pass on sushi culture to future generations.

“A lot of old places are actually closing now, and think about it, like 20 years down the road, the culture might just die off.”

It is both apt and ironic that in her mission to preserve Japanese culture, Choo had to first break down one aspect of it — the favouring of men over women in the kitchen.

Women aren’t expected to step behind the sushi counter, says Choo. Even the lady boss doesn’t do so.

“It's just like it's a man’s territory.”

Choo explains that the traditional thinking in Japan was that “if you’re non-Japanese, or Chinese, or you’re a woman, then maybe you should do something else. Not this.”

Which is why, when Choo first tried to find a job in the kitchens of sushi restaurants, she was rejected “10 times out of 10”.

Worked her way into the kitchen

When looking for work, many restaurants preferred that Choo took up a job as part of their service staff. However, after insisting that she be allowed to work in the kitchen, she was eventually employed as a dishwasher and a server in one of her first jobs.

Being in the kitchen allowed her to secretly help the chef with simple tasks like chopping. “That’s how I actually got to learn how to hold a knife”, she recounts.

Initially, the restaurant didn’t acknowledge that she was doing work in the kitchen, meaning that she would be doing kitchen work while dressed in the service staff’s uniform, an arrangement she describes as “very funny”.

Choo pressed on in spite of this.

“Once I got started in the Japanese cuisine, I cannot get out of it anymore because it’s so attractive... you’re feeling it with your heart, you’re cooking it with your heart.”

“You get trapped inside”, she grins, describing how she fell in love with it in the first place.

“I guess… I love it so much to not be able to give up. I gave up every other thing. Every other thing. Just to do this one thing.”

Choo seems to have broken down the barriers to entry by slowly chipping away at them in this way. “I work hard towards that goal. Can be slow can be fast. I don't know but I just do it,” she says.

And, having done this, she was then able to immerse herself fully into sushi culture.

"We don't talk about money, we don't talk about off days, we don't talk about working hours"

A day in the life of an apprentice in a sushi restaurant starts as early as 5am.

The workday can extend more than 14 hours till the end of dinner service, after which apprentices have to allocate three to four hours for their personal training.

Choo describes how leftover rice would be used for practice in making sushi rolls. Instead of seaweed, apprentices would use newspaper, which helps with practice as it is harder to cut. Instead of fish, apprentices would practise slicing konnyaku jelly made from yam starch.

Choo demonstrates delicate knife work by carving a leaf. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Choo demonstrates delicate knife work by carving a leaf. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

It’s an unforgiving culture of self-abasement, one Choo describes as both “professional” and “perfectionist”.

“You're always practising, practising just for that one moment when you are needed to perform, and you can do it, and you get acknowledgement in that sense. So the chance is always saved for the one who is prepared.”

Thus, she sought to prove herself by showing sincerity in learning.

This meant that Choo had to forgo things many would take for granted as basic employment rights, such as salary, leave days, and overtime.

“We don't talk about money. We don't talk about off days, we don't talk about working hours. Nothing. It’s just pure, ‘do you want to teach me?’”

This is why, when Choo playfully asks her mentors ‘why did you pick me in the first place?’”, their reply is that “we are sharing with you, and we love you so much, because your ‘eyes’ is right”, referring to a Japanese expression that, Choo explains, has the same meaning as the Mandarin word 眼神, which describes the expression or emotion shown in one’s eyes.

Choo carefully plates a dish over the counter. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Choo carefully plates a dish over the counter. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

“I’m a chef from my heart”

“I’m a chef from my heart. I have always been”, she said, adding that she even puts her whole heart into dishwashing.

“Maybe you think that it's ridiculous. Or maybe you wouldn't notice it if nobody pointed out to you, but when the plate is cleared, let's say there is a bit more green pea sauce. [...] Is it because this customer did not like peas? And then you can see the subsequent dish — if, let's say, there are sky beans also left over. So this means that it's just that the customer's preference is not beans.”

For Choo, the little things that are often overlooked trained her to become a better chef.

Learning how to conduct a traditional tea ceremony, or make a flower arrangement, helped her “to be balanced in pace, and in plating, and develop a good sense of space.”

Picking up shoes for customers also trained her patience, discipline and humility.

Because of this attitude, Choo was able to see learning opportunities in experiences others might deem undesirable.

Choo dishes out sushi rice from a wooden tub. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Choo dishes out sushi rice from a wooden tub. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

This humility is demonstrated in an episode she recounts to us: Once, Choo had a pot of hot sushi rice dumped on her head as punishment for allowing it to dry up from not being covered after use.

It wasn’t just the physical pain that hurt her, she says.

“It hurts my heart that because of my mistake, two kilograms of rice was wasted. I wasted the farmer’s harvest.”

Choo has continued in this vein to this day. She explains that respect for ingredients can come out of empathy for “the fishermen who don't get to eat dinner with their families just because he or she is out there fishing your fish.”

Reluctant to recognise her own achievements

Choo is, at first, reluctant to concede that she has anything to celebrate as an achievement or milestone, insisting that she will only be satisfied with her progress “when I’m being put into my grave”.

“My philosophy is that I will only reach the most perfect peak of me, when I’m being put into the grave. That's the best because when I die I cannot be better anymore — that's the best that I will be.”

She relents, however, when asked for advice for females who want to enter a male-dominated industry: “Don't give up. Persevere, [...] and be strong. And I'm sure they will make it too, just like I did.”

Choo getting ready to welcome diners into her restaurant. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Choo getting ready to welcome diners into her restaurant. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Today, Choo has the freedom to spend time travelling and learning, thanks to the fact that she can simply close the restaurant while she is away, as she has no full-time employees.

When she is around though, the restaurant is fully-booked — and it has been for years. In busy periods, Choo tells us that a prospective customer could be waiting for a month to get a seat at Kappou.

Pricing for accessibility

The price for omakase meals at Kappou starts at S$128, which comes across as pretty good value for money when you consider that each diner is served 14 to 16 dishes made from quality ingredients.

Choo has accepted requests from customers for higher-priced meals, with more premium ingredients, with one notable customer requesting that she prepare a S$500 meal. However, she has chosen to keep her prices as low as possible, explaining that “If I price it so high, people can’t try my food. Why not be flexible and make customers happy rather than putting customers on the spot to have an easier life for myself?”

Choo finds joy in making the cuisine affordable for a wider range of customers.

“It's really sweet to see young people who just started working really want to have good omakase, and they can enjoy it.”

This is surely one reason why, even without any marketing or advertising, Choo has built up a solid base of loyal customers, who make up around 80 per cent of her clientele. There are some who come as regularly as two to three times a week, and have lost count of the number of dishes they have tried.

She can also count on her regulars to refer their friends to her. Some international customers have even made bookings for their family members and flown them over for special occasions like birthdays.

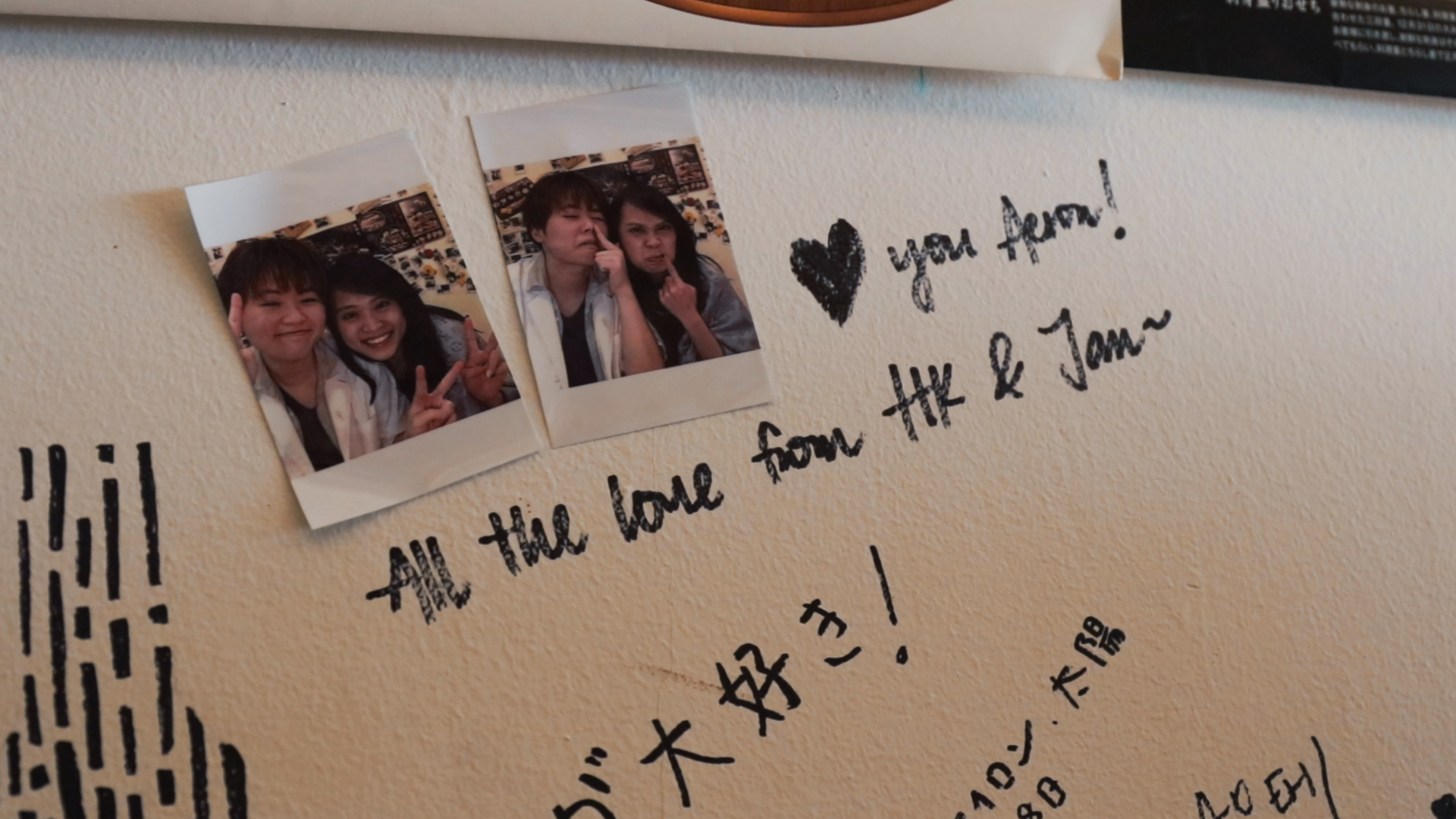

Photos of Choo and her customers adorn the walls, together with short messages left for her. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

Photos of Choo and her customers adorn the walls, together with short messages left for her. Photo by Valerie Ng and Juan Ezwan.

“It's just... big love”, she says, talking about the customers who have, over time, become her friends.

It was, in fact, her customers who brought her to the hospital, on one fateful day when she collapsed in the middle of service on Dec. 22, 2017.

“Both of my feet lost feeling and I fell flat on the floor, during a (day of) service. I could not walk. From my hip down there was no feeling.”

Choo later learned that she was suffering from a steroid cell tumour — a condition that had not been picked up despite regular health check-ups.

And it was customers who supported her on her road to recovery, writing her get-well-soon cards during her stay at the hospital, and flocking back to the restaurant as soon as she was ready to reopen.

Choo tells us how the discovery of her tumour sparked a reevaluation of life.

“Honestly, after being diagnosed with the steroid cell tumour and being somehow recovered from it, I guess now — of course — I try to strive for much better work-life balance as compared to before.”

After relearning how to walk and returning to work, Choo reduced her restaurant’s operating days from six to five, and now serves only one round of seating per day.

“I would say my passion for the food hasn’t reduced due to my health, but I'm trying to do work in a way that is more sustainable so that my customers will be able to enjoy my food for a longer run.”

She also spends more time coaching and mentoring her staff, something she considers vital to her trade — just as her mentors passed down their skills to her, Choo does her part in preserving traditional Japanese cooking and culture.

Her passion for serving up first-class cuisine and her newfound work-life balance come together in the extensive travelling Choo does every year: about a quarter of each year is spent travelling, she tells us.

On these trips, Choo isn’t just on a holiday, but rather a mission to learn and improve her skills. For instance, she would volunteer to help clean up at reputable restaurants for a chance to soak in knowledge from the establishment’s chefs.

Ever the perfectionist, Choo tells us she still has a long way to go before she’ll be satisfied with her own skills.

“I don't think I will ever (be satisfied),” she says without flinching. “I've already decided this road so I'm gonna really protect this road and really walk this road.”

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or making the world a better place in their own small way, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Andrew Koay. Some of Choo's quotes were edited for clarity.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.