In the midst of a global pandemic, there are few usual comforts to be had.

We can’t meet and console ourselves in the company of friends and loved ones (of the non-immediate family kind) in the way we’d prefer, and our favourite haunts have been deemed non-essential and shut down.

Even the once ever-glowing lights of the golden arches have been dimmed as McDonald’s closed their fast-food restaurants island-wide.

That’s why I am thankful that so far, I’ve still been able to enjoy the simple and familiar pau.

Yep, you didn’t read wrong or misunderstand, I’m talking about the pau — the soft, warm white steamed bun that comes with a wide range of fillings; just to name a few: tau sar pau, leng yong pau, big pau, veggie pau, salted-egg pau, and my personal favourite, the char siew pau.

There’s something about biting into a pau that makes me feel better about this whole pandemic. As my teeth rip through the fibres of the white husk before sinking deep into the bun’s warm centre, just for a brief moment, life doesn’t feel all topsy-turvy.

Lest you think I’m putting on a clinic in melodrama, allow me to take you on a walk through history (where else do you need to be, anyway?) to explain why I think the humble pau is the thinking man’s comfort food of choice in this age of uncertainty.

Plague-healing origins

This stroll begins in imperial China, in the Three Kingdoms period (circa 220-280AD). That’s when the pau, or baozi as it is known on the mainland, was said to have been invented.

As the legend goes, according to China Daily, the pau wasn’t created by a masterchef in the kitchen but rather a military strategist on the battlefield.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Fabled Chinese hero Zhuge Liang was leading his army on an expedition in the far south of China when a plague started to spread among his soldiers.

Seeing his men struggling under the cloud of this mysterious illness, the wise Zhuge Liang conceived a solution that would both placate powerful deities and soothe the sick.

He cooked up the first pau — an object that was purposefully shaped like a human’s head — as what he hoped would be an acceptable sacrifice to the gods. At the same time, the steamed meat-filled bun would nourish the weakened bodies of those infected by the plague.

Imagine what it must have been like for the strategist’s debilitated men to receive a hot steaming pau in their cupped hands on that very first day. They no doubt would’ve felt the strength and vigour return to their bones each time the fluffy bread and finely roasted meat slid from mouth to belly.

Kongming Lanterns. Image by Jirka Matousek via Flickr

Kongming Lanterns. Image by Jirka Matousek via Flickr

According to Vision Times, Zhuge Liang was quite a prolific inventor. He is credited as the originator of a semi-automatic crossbow, a type of rock formation with supernatural powers called the Stone Sentinel Maze, and the Kongming Lantern, which was used for sending military signals to allies at a distance.

However, none of these creations can hold a candle to the enduring popularity and persisting utility enjoyed by the pau.

Brought to Singapore on Cantonese junks

Needless to say, the pau took-off in imperial China after word spread of its battlefield heroics. Many different versions were spawned, with each city in the kingdom coming up with their own twist to the steamed bun.

Xiaolongbaos. Image by Yusuke Kawasaki via Flickr

Xiaolongbaos. Image by Yusuke Kawasaki via Flickr

In Shanghai, a popular variant was the xiaolongbao, which utilised minced pork and hot soup as fillings.

Yet, it is the Guangzhou variety of the pau that I love the most — the char siew pau.

The Cantonese combination of a doughy exterior with richly flavoured barbecued pork took two already existing and perfectly adequate foods and brought them together in a well-balanced union, a beautiful marriage far more significant than a mere sum of its parts.

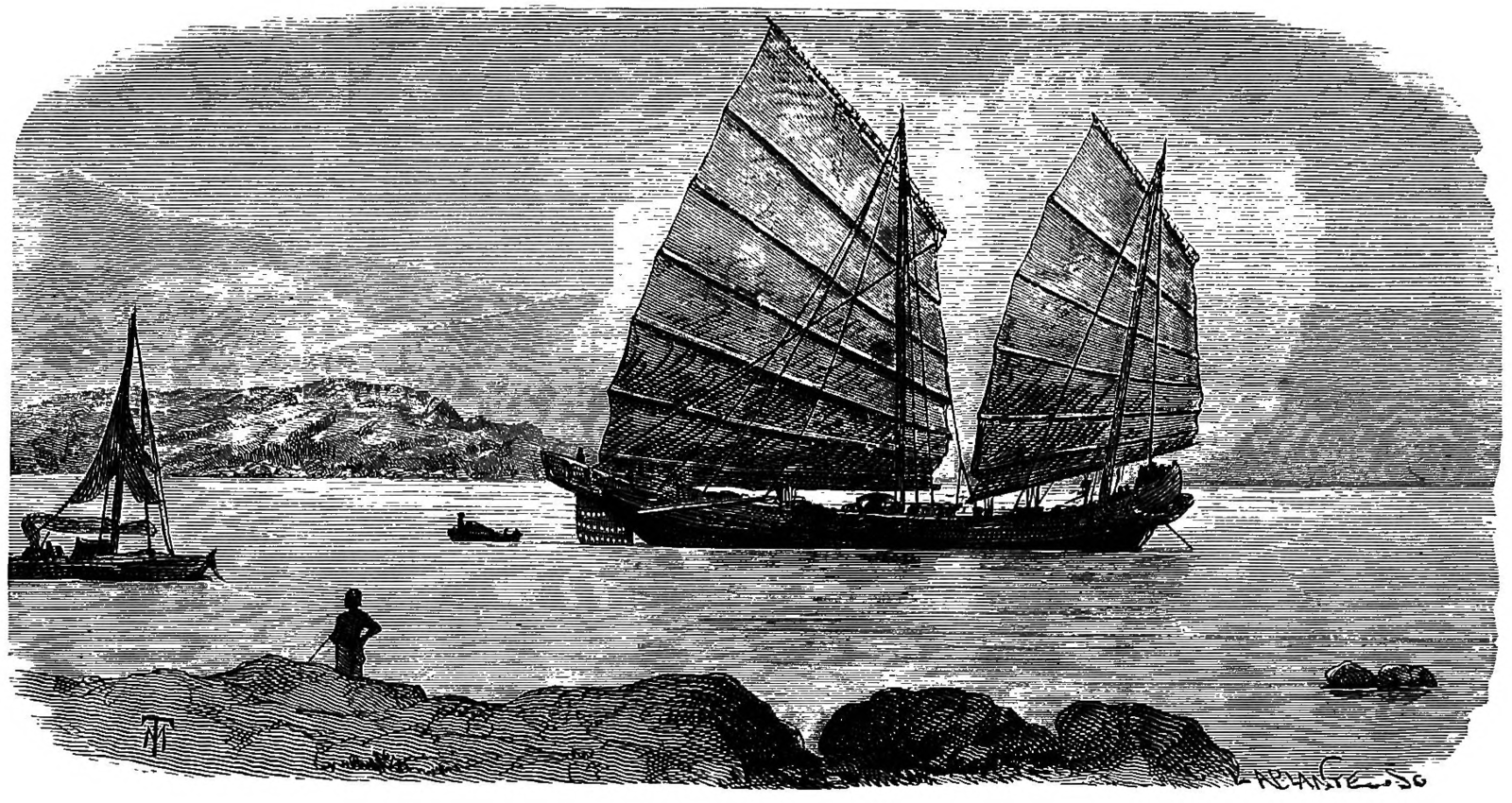

These pau-erful (heh) buns probably made their way to Singapore along with the waves of Cantonese migrants seeking a better life outside China.

Our very own Infopedia lists 1821 as the first recorded arrival of junk from Macao — the port of choice for Cantonese travellers leaving Guangdong. Records from two years prior — when Stamford Raffles founded Singapore — indicate that there were only around 30 ethnic Chinese on the island at the time.

Illustration of a Cantonese junk. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration of a Cantonese junk. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Feelings of loneliness and isolation would surely have littered the psyche of those early settlers back in 1821.

And without question, the comforts of enjoying the char siew pau would have provided some reprieve.

With each bite into the milky bun filled with sweet and savoury pork, the minds of Singapore’s early Cantonese pioneers would’ve been flooded with memories of the friends and family they left behind.

The simple act of gathering with other Cantonese settlers over a few paus might also have been the perfect antidote to homesickness.

Eventually, the popularity of paus required their production to be scaled-up.

Local family-run business Bee Sim was amongst the first to adopt pau-making machinery after moving their operations from a village home into a commercial kitchen in 1978. This allowed the mass production of the pau and its success is part of the reason the steamed bun is so widely available in Singapore today.

These days, some Singaporeans might be suffering from a different type of homesickness — the variant where we’re sick of being cooped up at home and isolated.

But if you ask me, there’s nothing like a hot pau to ward off the nasty vibes of cabin fever.

And with it being all the more important to stay at home as much as possible during this pandemic, Bee Sim’s factory-to-doorstep delivery services have made this simple delight, a convenient one too. During this time, they are committed to serving Singaporeans in-store quality dim sum — like loh mai gai and paus — that can be enjoyed with minimal effort and time.

Image by Bee Sim

Image by Bee Sim

Perhaps you think that I’ve been over the top in my praise for the humble pau.

But for me, the pau is a simple symbol of hope, that as a society we can overcome the pandemic.

In a time when humankind has once again been confronted by illness, the pau is a culinary reminder of wisdom and ingenuity in adverse health conditions. Its widespread enjoyment in Singapore is also a testament to the grit and determination of Singapore’s first Chinese migrants.

Maybe, some 1,800 years after Zhuge Liang, we too will find a solution to the challenges of today and emerge all the better from it.

Bee Sim has been at the heart of Singapore’s pau and dim sum scene for nearly 50 years. You can still get your pau fix from them here. They’re giving Mothership readers free delivery on orders over $40. Just enter the promo-code MOTHERSHIP to access this special offer.

This sponsored article by Bee Sim has made the writer hungry. Very hungry.

Top image by Bee Sim

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.