Jeremy Lim wears many hats.

Aside from being the co-director of global health at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health at NUS, Lim is also a partner at a global management consulting firm and the co-founder of a gut microbiome startup.

Somehow, on top of this all, Lim makes time to dedicate himself to serving a community that tends to be marginalised and forgotten in society, particularly so in the current climate of Covid-19: migrant workers.

And he does so through his work with HealthServe, a local NGO that offers medical care, counselling, case work, social assistance, and other support to migrant workers in the community.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

When I ask Lim how he manages to find time to volunteer with HealthServe, which he has been working with for the past seven years, he says frankly, "Well, I would say that we never find time; we make time. And it's really about prioritising the things that are important to you, you then find the time to do so."

Volunteering with HealthServe

HealthServe operates three clinics in Singapore, located at their main office in Geylang, at Jurong, and at Mandai.

They are almost fully volunteer-run, and where migrant workers are able to access medical care for only S$8.

Back in 2013, Lim joined as a regular volunteer general practitioner (GP) at HealthServe’s clinics, which he continued for a number of years before transitioning over into his current role as the chair of the medical services committee.

In fact, on the day of our meeting, he has just returned from a trip to Dhaka, Bangladesh with HealthServe, where he sought to develop partnerships to better support workers' mental wellness and establish care networks for workers once they go home.

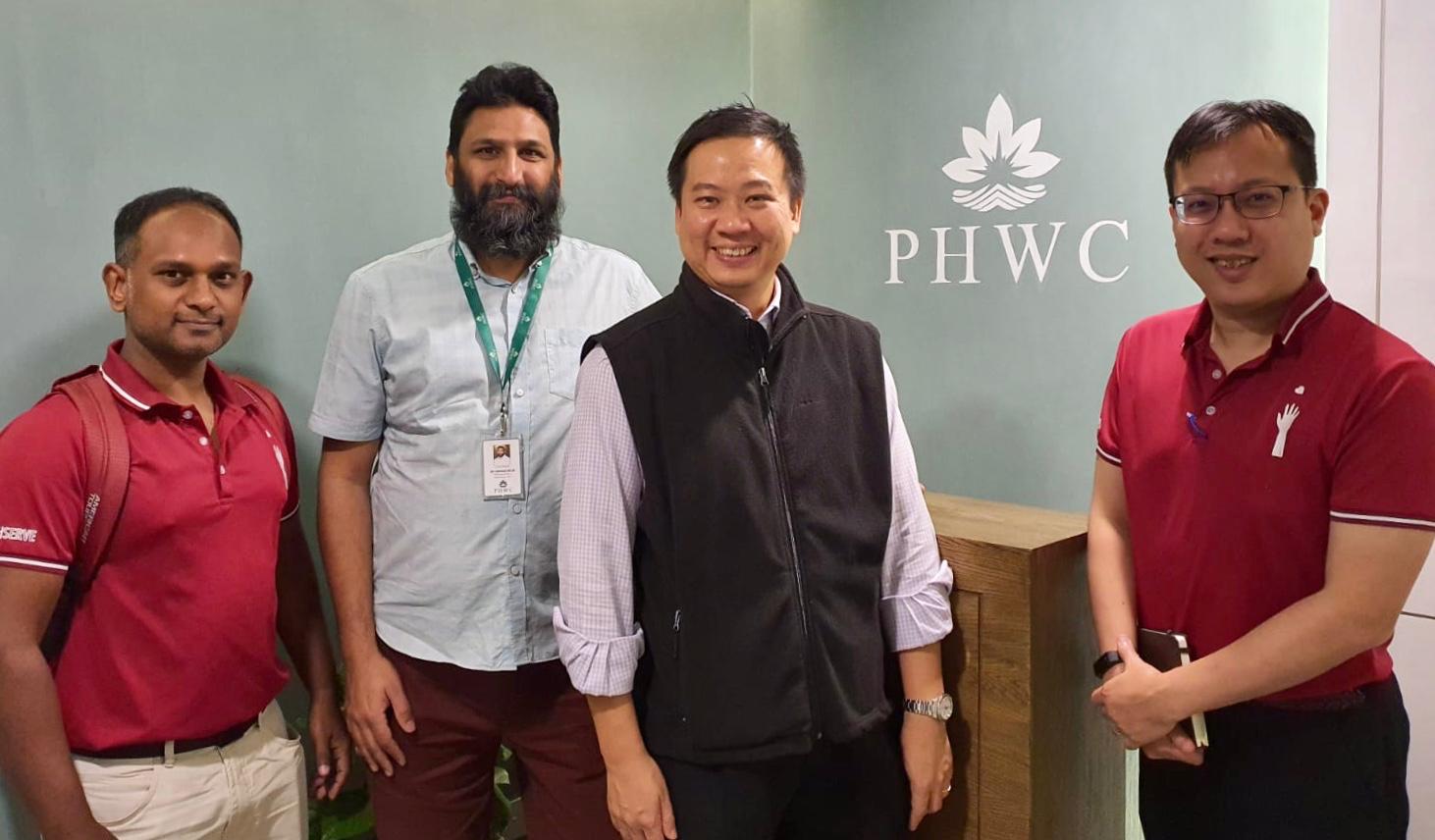

Lim (second from right) in Bangladesh to set up partnerships for HealthServe. Photo courtesy of Jeremy Lim.

Lim (second from right) in Bangladesh to set up partnerships for HealthServe. Photo courtesy of Jeremy Lim.

As a result of his switch to the administrative side, Lim hadn't volunteered as often at the clinics themselves in the more recent years.

However, that all changed nearly a month back, thanks to the Covid-19 situation.

Effect of Covid-19 situation at HealthServe clinics

After the announcement of DORSCON Orange in early February, the directive was given that doctors working in public institutions should not cross from one healthcare institution to another, in order to avoid cross-infection.

As a result, HealthServe was hit by a sharp decrease in volunteers, says Lim, with numbers dropping by 90 per cent. It had to close down its clinics in Jurong and Mandai.

HealthServe's Geylang clinic, which continues to operate three evenings a week, is facing extremely high demand.

HealthServe's Geylang clinic. Photo via Facebook / HealthServe.

HealthServe's Geylang clinic. Photo via Facebook / HealthServe.

Lim explains that the standard procedure at HealthServe's clinics is that patients are given queue numbers, and once the queue numbers run out, the rest of the workers must seek help elsewhere or come back another day.

On an average day, workers would start lining up for queue numbers between 30 minutes to an hour before the clinic opens.

However, in the current situation, Lim says that he has felt a little concerned seeing patients arrive five to six hours before the opening time in order to wait for queue numbers.

He emphasises that having more volunteers during this time would help ensure that workers who need medical support would be able to receive it, a sentiment echoed by HealthServe in a Facebook post about an urgent need for volunteer GPs and dentists.

Volunteers because it's the right thing to do

Unlike many of HealthServe's regular volunteer doctors, Lim is able to see patients at HealthServe's clinics during DORSCON Orange because his other roles are not patient-facing.

Thus, HealthServe is his one and only practice site, which satisfies the DORSCON Orange recommendations.

He finds contributing his time to HealthServe important because it is his way of trying to "meet unmet needs".

He tells me candidly that until fairly recently, migrant workers' issues were not the most popular cause, and developments in the Covid-19 outbreak — a cluster involving five Bangladeshi migrant workers and the raging epidemic in China — have made it even more challenging.

When I ask him where his willingness to work with people who others might be turning away from in the current climate comes from, Lim says, not skipping a beat, "If we who can don't do it, then who will?"

"It is the right thing to do. I mean, surely, those of us who have been very privileged, in that we are not lacking for anything materially, right, and we see the needs, and it's hard for others to essentially plug this gap, and so we basically step up in whatever little ways that we can."

He adds,

"I think we do have to recognise that these migrant workers that we are afraid of at the train stations, these are the guys who work with us Singaporeans to help build this country.

And so, there is a certain, I guess, duty that we as a country owe to the people who help us to make Singapore successful."

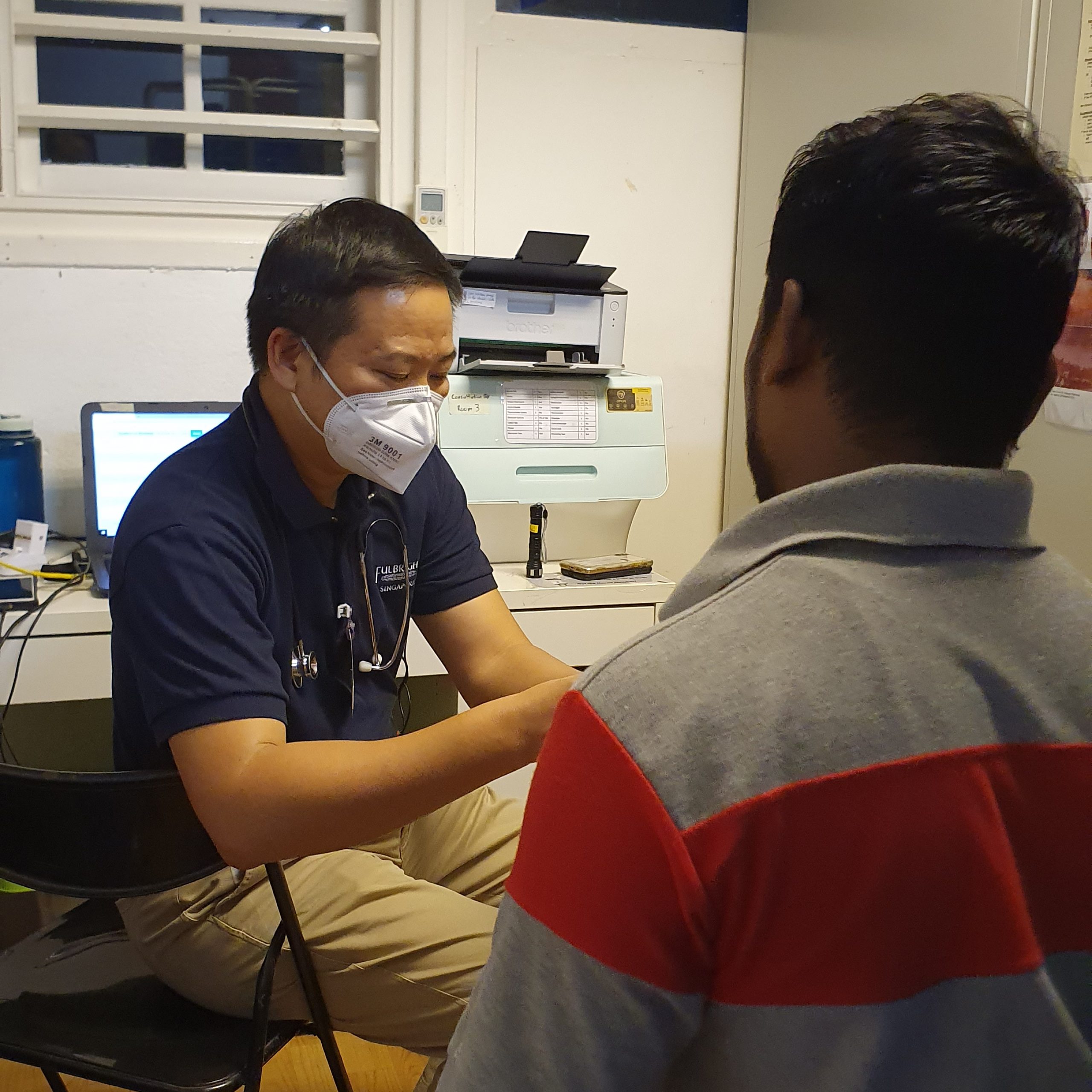

Lim volunteering at the HealthServe clinic. Photo courtesy of HealthServe.

Lim volunteering at the HealthServe clinic. Photo courtesy of HealthServe.

Migrant workers at higher risk during public health crises

Low-wage workers, such as migrant workers, are at higher risk when it comes to public health crises, as pointed out in a commentary by researcher Qiyan Ong and Nominated MP Walter Theseira, local academics in social services and economics.

Lim refers to this, noting that when the government announced the distribution of free masks to every household in Singapore, migrant workers were not included in those measures.

"They tend to be omitted when we think about public health planning in terms of resource allocation, because they are just a less visible population", says Lim.

In addition, the fact that the workers have less financial capabilities means the societal resources they are able to mobilise are far smaller, making them as a group more vulnerable.

If the companies that employ migrant workers collapse during these economically difficult times, he says, then the workers will be "left out in the lurch".

And while the general advice during this time has been to avoid congregating in crowded places, Lim points out that many migrant workers do not have the option to do so, due to the fact that many of them live in dormitories.

"This is home for them. And there's no alternative to disperse, to reduce risk of these clusters forming within the dormitories", he says.

And taking care of the most vulnerable groups amongst us is of utmost importance, says Lim.

“Frankly, if they are at higher risk, then all of us become at higher risk also, because in managing outbreaks and epidemics, the chain is only as strong as the weakest link.

And if we don't proactively look after the weakest link, then collectively, we will all pay the price.”

Migrant worker community worried and scared, keeping themselves away from locals

Lim emphasises that migrant workers do not pose any higher of a risk to the Singaporean public than anyone else, and that people should not be scared of them.

"The migrant worker community is equally concerned about Covid-19 disease as the rest of Singapore society, and rest assured that the migrant worker community is likewise very, very proactive with hand-washing, with use of sanitisers."

He also adds that, based on his conversations with patients at the HealthServe clinic, many of the workers themselves are afraid.

In particular, the Bangladeshi workers feel afraid knowing that one of the five Bangladeshi workers who have been infected with Covid-19 virus is critically ill.

Sadly, the foreign workers he has spoken to are also mindful of the Singaporean public's reactions to the virus to the point where they consciously segregate themselves from locals:

"They're also aware that the Singapore public is, I guess, of heightened awareness.

So what some of the patients have shared during the consult is that they try to, like what all of us should do, they stay away from really crowded areas, and I think that they've been especially mindful to not go to where many Singaporeans hang out.

And is it because they feel uncomfortable or they don't want to make the Singaporeans feel uncomfortable, we didn't probe so much.

But I think that that at this point in time, many of the workers are really keeping a very low profile."

S'pore is generous enough to help every group

In a recent Straits Times commentary Lim wrote, he said that all decisions about public health measures have tangible human consequences to consider, adding, "We should impose controls with a heavy heart and with full appreciation of those who will suffer from our decisions".

Therefore, he opines that the government's decision to reject all new work pass applications by workers from Hubei province is "fully understandable" from a public health and containment point of view.

However, while decisions like quarantine measures and closing borders might technically be the right things to do, from a public health standpoint, we have to recognise that they have "very real human consequences".

Lim believes that every sovereign government's first duty is to its own citizens, but points out that we are all also part of a global community:

"I would not see this as a zero sum game, that if we help Singaporeans, we cannot help migrant workers. Surely, as a country, as a society, we are big enough, we are generous enough, to do what we can for every group."

And while it's important to sympathise with the very real fear that comes with unknown infections, Lim says he finds any expression of xenophobia to be very unfortunate and disappointing.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

"Do we have xenophobes here in Singapore? Yes, of course we do. Should we give them platforms to amplify, and to, in a sense, agitate the ground? The answer is no."

Thus, we need to be proactive about avoiding these xenophobic sentiments, and Lim hopes that various social media platforms can "help to curb these basal instincts and help bring our better angels out" in order to rise above them.

How Singapore's handling the Covid-19 outbreak: "Everyone is very sincere and trying to do the right thing"

In terms of Singapore's efforts on the Covid-19 front in general, Lim's perspective of seeing things on the policy side as well as on-the-ground has enabled him to find empathy with everyone involved:

"This entire situation is not like a bad D-grade cowboy western, where there are good cops and bad cops and so on.

Everyone is very sincere and trying to do the right thing. We are, as a system, under tremendous constraints.

I think people are doing a phenomenal job, whether at the individual level or at the collective level, in the Ministry of Health or the multi-agency taskforce."

However, he notes the importance of the country ensuring there are enough supplies, especially for our frontline healthcare workers, depending on how long the situation is expected to last — therefore to his mind, Singapore has done well in being conservative where needed.

"Because if if our GPs and all feel that they're no longer safe, or they're no longer adequately protected and they close their clinics, then I think Minister Chan is right that the system will just collapse", he said, alluding to the leaked audio of Minister for Trade and Industry Chan Chun Sing, which Lim says he felt "painted the stark realities very well".

"I'm glad we have a lot of toilet paper in the country now," he quips, referring to the mass panic-buying the occurred in supermarkets after DORSCON Orange was announced.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

"Plausible" that Covid-19 is here to stay

Nonetheless, Lim cautions that Singapore must be prepared to accept that the coronavirus might be here to stay for a long time.

One "very plausible scenario", says Lim, is that Covid-19 becomes endemic.

This means that it would be a global issue, and that living with coronaviruses and other novel infections would just become "part of the new normal", similar to the common flu and hand, foot, and mouth disease.

This will also require the changing of mindsets and the development of new norms of social etiquette and sensible hygiene measures, such as carrying around hand sanitiser and not shaking hands with one another.

I cringe and apologise for having initiated a handshake with him when I first arrived for the interview, to which Lim offers a good-natured "no worries".

"Keep calm and carry on," he says, adding that the important thing to focus on is not the absolute number of cases as numbers are just a function of case definitions and of how thorough surveillance and contact tracing are.

And when it comes to contact tracing, Singapore is "unrivalled in the world", he notes.

Rather than numbers, what we need to watch out for is the emergence of multiple cases that are unlinked to any cluster.

"If that happens", says Lim, "then we can safely conclude that there's widespread community transmission, which also signals that the period of containment should rapidly close, and we then move to a different phase, which is mitigation".

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

Photo by Rexanne Yap.

Through it all, though, life must still go on, he says.

It doesn't make sense to not go to school and to cancel events such as weddings due to the virus, because we don't know how long it will stretch on for.

He asks, "If this carries on for two years, does it mean we're just going to stop everything for the next two years? Surely the answer has to be no."

We should be careful and concerned, but not paranoid, for the safety of ourselves, our families, and our fellow Singaporeans, Lim says.

"Let's take sensible precautions and trust that the authorities are doing everything that they can, guided by good science."

And this trust must extend to each other as well:

"We should trust that that we have tackled rough times before, and that we will figure out, not just individually but as a society.

And I think ultimately we have to trust that as fellow Singaporeans, we'll look after each other; whether those who are affected by the disease directly, whether those who are economically worsened by some of the containment measures, and so on."

After all, he says, "It's these epochal periods that really define — are we a great nation, or are we not?"

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or making the world a better place in their own small way, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top photos via Rexanne Yap and Facebook / HealthServe.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.