Sometime in September 2015, Fatin Nuwairah, 14, returned home from school and turned on her smartphone to see a notification.

To her excitement, she’d received a picture of some sort from a friend on Kik Messenger, an instant messaging application.

“Chris sent you a picture,” the notification read.

Connecting over a mutual love of anime

Fatin had met Chris about a month prior, on a public Facebook interest group where over a thousand fans of Japanese animation (or anime) gather to discuss their mutual admiration for the art form.

Describing herself as an active member of the group, Fatin would often ‘like’ or ‘comment’ on posts that piqued her interest.

One post in particular called for group members to leave a comment naming their favourite anime series.

“Hey, I like this anime too!” said a stranger named Chris in reply to Fatin’s comment.

And from there they hit it off.

A few replies in the comments later, Chris and Fatin were messaging each other privately over Facebook messenger.

“He personally messaged me on Facebook, but he said that he didn't use it regularly. So he recommended using Kik instead,” said Fatin.

“So like, I happily obliged cause we were getting acquainted with each other at that point in time.”

Online friends

Chris, it turned out, was 24 and European — though Fatin can’t remember the exact country he was from.Over the next week, they would exchange experiences of what it was like to live in Asia as opposed to Europe, while also chatting about their favourite anime.

Never mind that he was a whole 10 years older than her and someone she’d met online — Fatin was used to making “online friends” who were significantly older than her.

“I made my first online friends when I was like 11; I got Facebook when I was 9. It was from an online writing community on Facebook. So most of (my online friends) were actually in their 20s.”

A precocious fiction writer, Fatin had no problems holding her own in conversations with adults whom she saw as genuine friends.

Chris was no different.

Every evening after school, Fatin would be on Kik Messenger chatting away with him.

“Like I felt like a sense of trust with him,” she told me.

“I tend to trust people until they give me a reason not to. Once I start talking to them and I can tell that it’s very fun to chat with them, I immediately — I kind of make myself vulnerable already, in that sense.”

"It seemed like a very 'jokey' question"

That trust persevered even when Chris started getting weird, about a week after they first started talking.

“He asked me if I watched any NSFW (not-safe-for-work) anime genres,” she recalled.

While the question came as a shock, Fatin didn’t think much of it — “it seemed like a very 'jokey' question”.

Yet as the days and weeks went by and their texting persisted, Chris started to get more suggestive, more explicit in some of the areas he steered the conversation to.

Eventually, many of their conversations became unambiguously sexual in nature.

“He even asked if we could exchange nudes. I told him no, because it didn’t feel right. And he said ‘I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it cause I’m not going to share it with anyone else, it’s just for my own pleasure’.”

On one occasion, Chris even subjected the 14-year-old Fatin to an excruciatingly detailed description of “what he would want to do to me if I was in his bed”.

“I was very hesitant about how to respond. It’s like I’m trying to hint that I’m not very comfortable with it and attempt to change topic. I didn’t say it directly that I wasn’t okay with it.

He wasn’t doing it all the time, I guess, that’s why I was still able to tolerate him. And I guess I considered him a friend because of our common interests.”

The picture

Weeks of awkwardly tip-toeing around topics that unsettled her finally came to a head in September 2015, when Fatin opened Kik Messenger to see that Chris had sent her a picture of his genitals.

“I felt very violated,” she said.

“The photo came off as a shock. My first instinct was to just block him. I didn’t really want to talk to him anymore, it felt very scary suddenly seeing something like that.”

Fatin subsequently deleted the application before erasing any correspondence she’d had with Chris.

Digital natives

Fatin Nuwairah, five years after a stranger attempted to groom her online. Image by Andrew Koay

Fatin Nuwairah, five years after a stranger attempted to groom her online. Image by Andrew Koay

These days, Fatin comes across as any 19-year-old digital native would.

When we spoke, she told me of the different social media platforms she uses; WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram, Reddit, Tik Tok — she runs the gamut of applications frequently used by any young person in her generation.

Somewhat surprisingly, given her previous experience, she has not shied away from the romantic socialising tools of this age either — dating apps.

The eldest of three children, she also encourages her siblings to embrace social media:

“My siblings will watch TikTok with me,” she told me of her brother, 12, and her eight-year-old sister.

“I’m the one dragging them to the table to watch TikTok.”

But perhaps more than others, she’s very aware of the dangers facing users of technology — who are only getting younger with each passing generation.

“I need to protect my siblings online also, cause they like to play Roblox (an online game that describes itself as a ‘global platform that brings people together through play), they like to use YouTube.

I have a cousin the same age as my sister, like 8 years old, and she uses TikTok. The way she dresses up, even like wearing the school uniform, sometimes it concerns me.”

“I actually tried to report her account in the hopes that TikTok would like take it down,” she said between laughter. “But it didn’t work.”

Online child grooming

She’s not wrong to be cautious either.

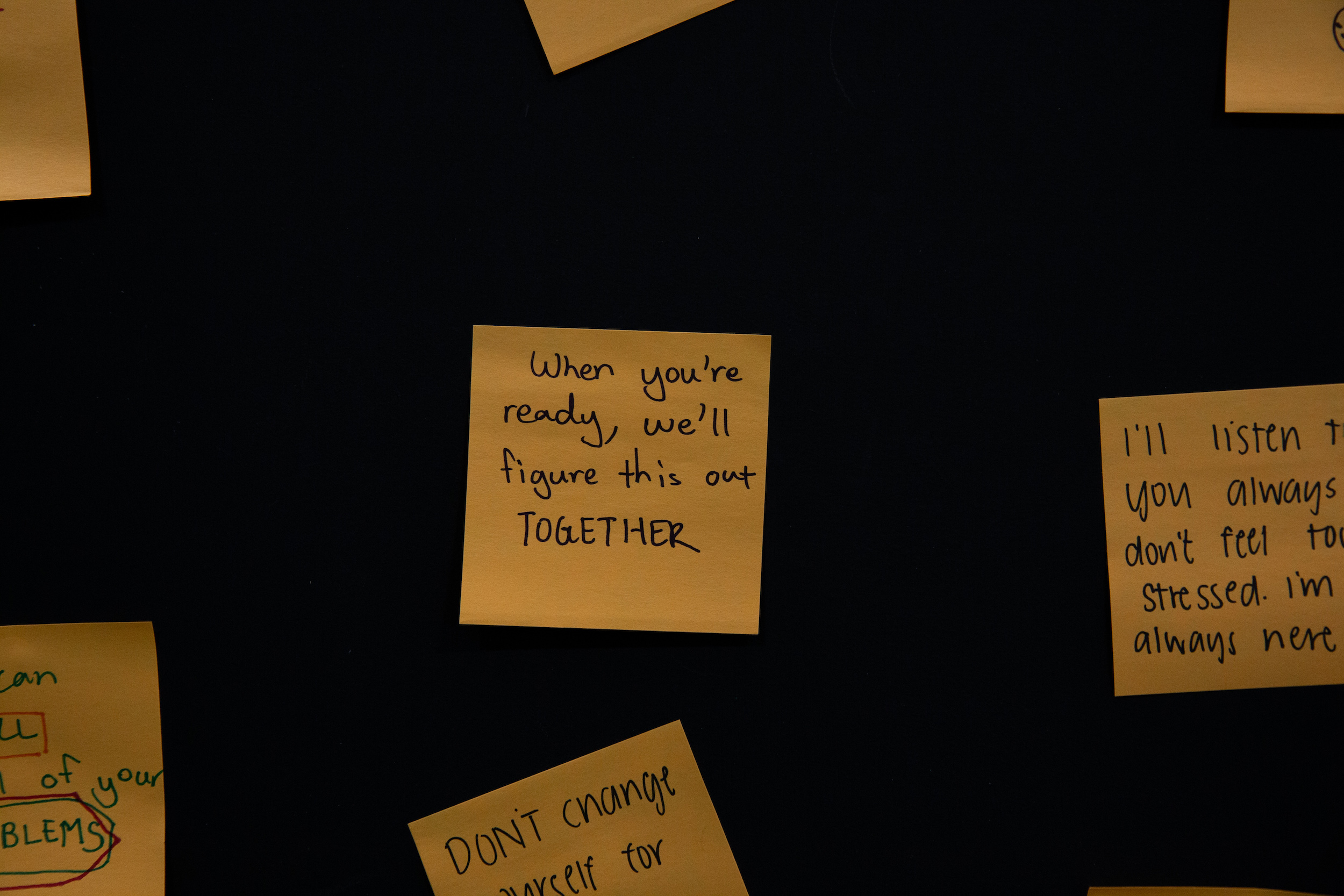

In fact, Fatin and I were talking at an exhibition put on by Flag, You’re It — an initiative focused on bringing awareness of and educating the public on the growing threat of online child grooming.

This is where online platforms are used by predators for the purposes of forming a trusting and emotional relationship with the goal of exploiting a child for sexual benefits.

Vanessa Tan, one of the initiative’s founders, told me that among the 400 students they surveyed, about one third reported that they’d either been the victim of online child grooming or knew of a friend who was.

The 24-year-old also pointed to Microsoft’s Digital Civility Study of 2019, which found that two in three youths in Singapore had received unwanted sexual content online.

50 per cent of youths in Singapore also reported encountering unwanted contact from an online stranger, according to the study.

Couple that with a 2018 report by The Telegraph — which quoted the United Kingdom’s National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) as saying that children could be groomed online in as little as 45 minutes — and it's not hard to see why this is a growing problem for the digital generation.

However, the biggest hindrance to fighting online child grooming might actually be the lack of awareness that it even exists.

“Actually now when we talk to people with these experiences, there isn't a term — like online child grooming — that pops into their head,” said Vinice Yeo, another of Flag, You’re It’s founders, also 24.

Tan agreed, adding that all the initiative’s four founders had friends growing up who experienced online child grooming; though they were none the wiser about what was actually happening despite knowledge of the interactions.

Keeping quiet, blaming herself

For someone like Fatin, who comes from a deeply religious family, even telling others about such interactions can be hard.

Fears of stigmatisation and punishment have kept her from telling any of her friends or family about the incident.

In fact, the first time she opened up about her experience with Chris was when she chanced upon posts by Flag, You’re It about online child grooming on Instagram — five years after the fact.

“I actually reinstalled the app yesterday,” she told me.

While the conversations from what must feel like a lifetime ago were wiped clean, Chris’ profile was still there.

It brought back bittersweet feelings of nostalgia for Fatin.

“It just made me feel odd I guess. When I was looking at his profile photo and his username — it’s like even his username was still very anime-related so in a way I can still sort of recall what it was like chatting with him as a friend, before all this happened.”

Even now as she looked back on the incident, her first instinct was to shoulder some of the blame.

“I think there was a sense of confusion and betrayal, I don’t know if that’s the right word for it. Cause I trusted him, and I guess it felt like I didn’t really set any boundaries per se and that’s why it was easy for him to push it.”

It’s a cliche, but I felt compelled to reassure her that it wasn’t her fault; though in all likelihood, it was probably inadequate to undo five years of silent internalising, agonising over the incident and what must have led up to it.

The irony is that in an age where people are connected more than ever by technology, traditional relationships are as disconnected as ever.

Someone might have no problems publishing a 1000-word blog post about their experience with sexual misconduct, yet shy away from confiding in loved ones about their trauma.

It’s not hard to imagine that left to their own devices, adolescents might develop unhealthy thought patterns or fall into predatory relationships.

The Flag, You're It team (L to R) Esther Soh, Vanessa Tan, Vinice Yeo, Stephanie Wong. Image courtesy of Flag, You're It.

The Flag, You're It team (L to R) Esther Soh, Vanessa Tan, Vinice Yeo, Stephanie Wong. Image courtesy of Flag, You're It.

Looking beyond the knee jerk reaction

“That’s why their (Flag, You’re It) platform is important,” said Fatin, laughing and fully aware of how much she sounds like an informercial.

She explained that some of the materials published by the initiative have helped her to have more open conversations with her friends, especially those who are younger.

“With the platform I was comfortable enough to share, warning them that there were dangers online. With the research that they produced — like the signs of a groomer, or the signs someone is being groomed — like I also can share with my friends — since I’ve been through it before — I told them ‘hey you can refer to this, and if you’re being groomed you can just tell us in the chat group, and we’ll do our best to talk to you about it’.”

The knee-jerk reaction for anyone reading this might be a resolution to bar kids from social media or at least limit their screen time.

And while that may very well be a sensible short-term solution, it misses the larger context by which online child grooming happens.

We’re living in an age where this hyper-level of technology-aided interconnectedness is the norm; teens have grown up familiar with the vast reach of online communication, one that far outstretches that which their parents were familiar with.

The methods of conveying information vital to any young person’s social life exists online. I was told as much by Fatin — “I feel like I’ll be missing out a lot if I don’t have Instagram”.

That’s why the silver bullet — if there is one — is not to shun the topic of online child grooming, but to talk openly and honestly about it. To make the space safe for those who have encountered predators to come forward, and to help them make sense of their experiences.

Image courtesy of Flag, You're It

Image courtesy of Flag, You're It

Flag, You’re It is currently holding an interactive exhibition at the National Library Building called “45 Minutes in the Preyground” which immerses visitors in the three stages of grooming.

More information about the exhibition and online child grooming can be found here.

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or making the world a better place in their own small way, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top images by Andrew Koay, coindesk.com

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.