Singapore's streets are known to be quite safe, by and large. Singapore's cyberspace, however, is not.

Even as the number of physical crimes here saw a decrease in 2019, the overwhelming increase in the number of scams that racked up victims in Singapore culminated in more overall crime compared to 2018.

This uptick is mainly due to scam cases, particularly e-commerce scams, loan scams and credit-for-sex scams.

And so Carolyn Misir, a Principal Psychologist from Singapore's Police Psychological Division, spoke to local media on Monday (Feb. 3) to give her insights on how scammers "brainwash" victims, and also shared a few techniques a victim can use to break free from the deceit.

Today's scammers employ psychological tactics

Misir found that most scam victims have an optimism bias, which means they overestimate positive events and underestimate negative events in daily life.

Therefore, if you think you're not susceptible to scams, you have already disadvantaged yourself.

Most likely, scammers will prey on this optimism bias, Misir said.

Coupled with the fact that Singapore really does have low crime, a lot of scammers take advantage of their victims' bias to make themselves look as legitimate as possible.

Forget the unsolicited text message full of grammatical errors or the scam caller with a heavy foreign accent.

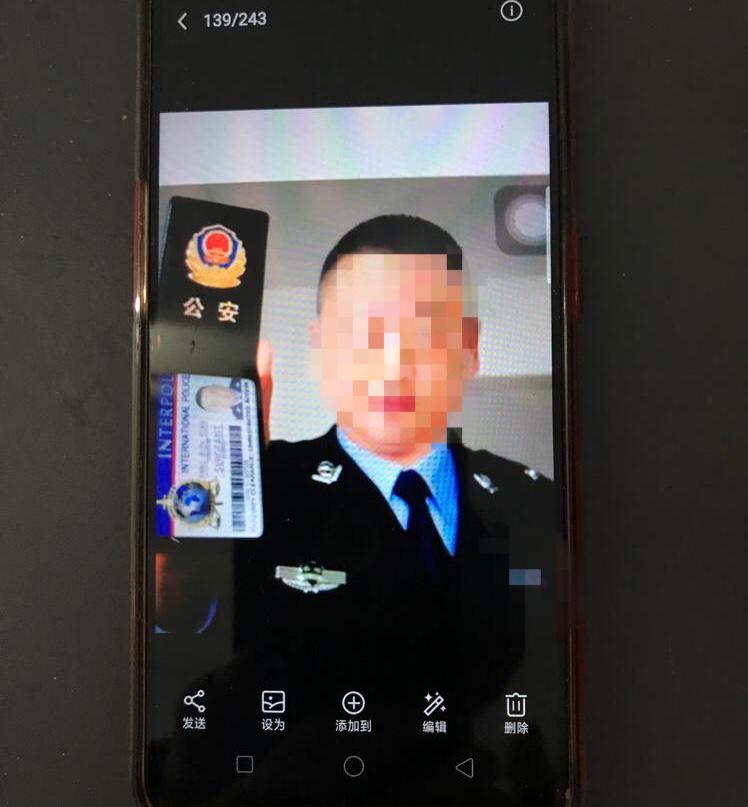

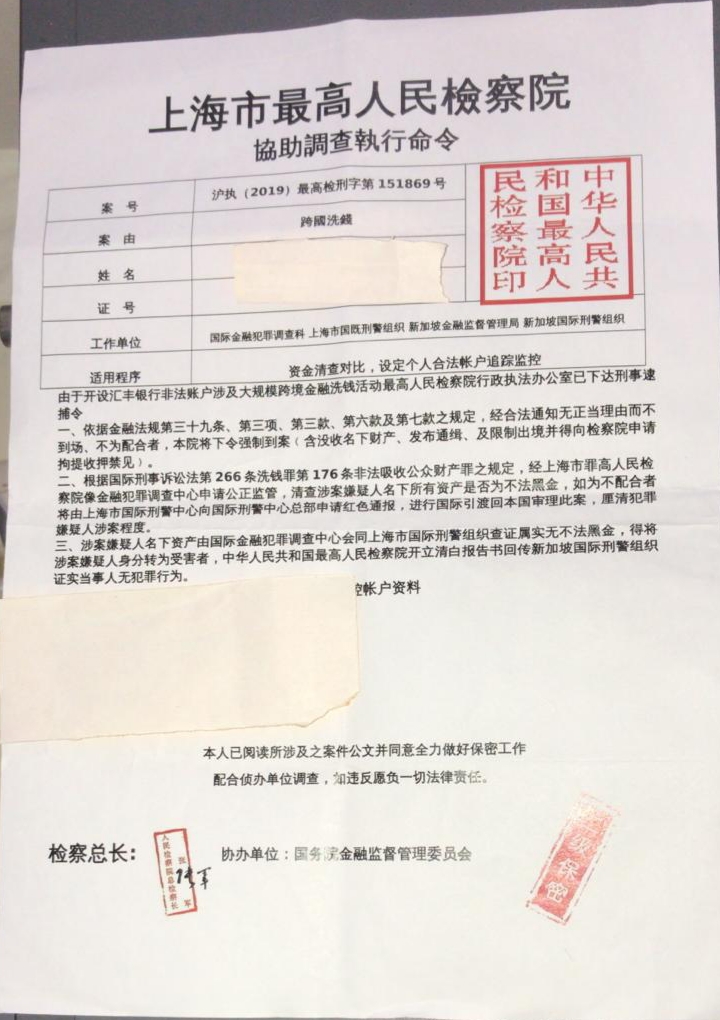

Granted, those aren't all gone, but today's scammers are large syndicates that recruit local-looking runners, set up sophisticated websites, and provide tangible-looking "evidence".

Scammers would send pictures of 'themselves' in uniform, holding up a warrant card, to look like an actual Chinese official. (Photo courtesy of Singapore Police Force)

Scammers would send pictures of 'themselves' in uniform, holding up a warrant card, to look like an actual Chinese official. (Photo courtesy of Singapore Police Force)

This document supposedly is designed to make a potential victim think they are indeed wanted criminals by Chinese police. (Photo courtesy of Singapore Police Force)

This document supposedly is designed to make a potential victim think they are indeed wanted criminals by Chinese police. (Photo courtesy of Singapore Police Force)

These scammers also keep their victims in a highly stressed state, dismantle their trust in close companions, and "brainwash" them to comply with their every demand.

Misir describes these techniques were "more intensive than advertising" — a normal smartphone advertisement might have one or two persuasive techniques to convince a buy; in comparison, "in one scam call, there are already five or six different compliance techniques that are being played out," she said.

That is how some victims could be cheated of their life savings in the span of nine minutes, over a roughly half-hour phone call.

Misir laid out the stages of the scam process, using a China official impersonation scam as an example.

The scam process

1. Introduction

An unsolicited call comes in, and an automated voice prompts a potential victim to press a number on their keypad.

"This is already a filtering process for the scammers because when you press the number, you're already vulnerable," said Misir.

The scammer would say that the victim had committed a criminal offence, and needed to assist in investigations.

This is when scammers would use social proof to make themselves seem as legitimate as possible. The caller would switch to speaker mode and there might be noises or voices in the background that make the situation seem authentic. This makes the victim feel, "If someone else is doing it, it must be real".

The scammers would then offer "help" to the victim, sometimes telling them not to cry, and feigning empathy to persuade victims into trusting them.

2. Threat

Victims would then be threatened with the consequences of their "illegal involvement", such as having their bank accounts frozen or citizenship revoked, which heighten their anxiety.

"The burden of proof is never on the scammer's part. It is always on the victim's part," said Misir.

The scammers would ask for the victim's personal details to prove their innocence and even demand that they report their movements over the following days.

3. Demand

Having obeyed the scammers' previous requests, "victims would have already been set up in many ways to comply with the scammer's demands," said Misir.

Scammers would send out local-looking runners to retrieve banking tokens, give out SIM cards, and provide up-to-date websites that legitimise and intensify the threat.

Because these tactics look authoritative, victims are inclined to give money, as they believe that their situation is real.

4. Realisation

Later on, victims would check their bank account to suddenly find large sums of their money — or all their money — gone.

This is when they finally tell their close friends or loved ones and realise that they might have fallen prey to a scam.

Some may feel a sense of shame or denial, which makes them reluctant to tell anyone else or even to lodge a police report.

However, the longer a victim delays reporting, the less likely they are to be able to recover their money lost, as time is critical for police investigations to be done.

Transfers to foreign banks usually cannot be recovered — the recovery rate for cases where funds were stolen and sent overseas was just 35 per cent last year.

So, how does one avoid falling victim to a scam?

1. Expect there to be scams. Verify, verify, verify.

The first way to avoid being scammed is to anticipate potential scams and to exercise a heightened sense of vigilance when transacting online.

"When you are online, doing any sort of banking, you make yourself vulnerable," said Misir.

To protect yourself, Misir advises to always verify any information you are given.

Doing a quick online search, calling someone else to clarify doubts or inform others of potential transactions could reveal the scammer's lies.

2. Take cognitive breaks from the situation.

Another method, she says, is to "take cognitive breaks". That means to separate yourself from the tense situation and give yourself some breathing space to think. Call someone else to discuss the situation.

Contradictions in the scammer's story can often emerge more clearly when you do this, allowing you, a potential victim, to see through the ruse.

3. Be around or close to your family.

The police also stressed the importance of having vigilant family members. Family and close friends who notice unusual behaviour could be crucial in identifying a scam.

In fact, some victims were so brainwashed that they would not believe actual police in uniform visiting them in their homes, informing them that they have been scammed. In the end, they only realised something was amiss when their family members intervened.

Post-scam trauma

Being scammed of large sums of money can be very traumatic, too, notes Misir, who shares that in some severe cases, victims need counselling, seek psychological treatment, and in one case she is aware of, become suicidal:

"So it is actually very real. It's as real as being attacked in person. You are being attacked online and you lost a lot of money, you've lost your sense of self esteem, your sense of justice, your sense of being safe."

As scammers become smarter and more sophisticated, our police continue to remind the public that the nature of today's scams requires us to be more alert, for both ourselves and our loved ones.

Top photos by Rexanne Yap and NCPC/FB

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.