Always a commando, published in 2019 by Marshall Cavendish, tells the story of Singapore army pioneer Clarence Tan.

The book, which you can buy a copy of here, is written by Thomas A. Squire, Tan's son-in-law.

The book tells the story of Tan's experience joining the Singapore Volunteer Corps in 1959, eventually becoming the first commanding officer of the Commandos in the newly-formed Singapore Armed Forces.

We reproduce an excerpt from the book recounting Tan's experience in recruiting and training the first batch of commandos.

***

By Thomas A. Squire

How do you recruit people for commandos when the armour division can flash their tanks?

It was hardly an impressive beginning. A small office in a quiet corner of SAFTI was to be the unit’s first home.

And while four officers had been formally posted to the unit from day one, this first home was initially occupied by just one man (who was therefore the acting commanding officer for a few weeks).

The other three were finishing off existing commitments – one was on a course a few buildings away at SAFTI’s School of Advanced Training for Officers, while two had been sent overseas to attend commando and paratrooper courses.

Clarence himself was not a part of this initial four. While he was still very much involved with the new unit’s development at a management level, he remained at 4 SIR for a while longer before ultimately being posted to the commando unit as its first commanding officer.

The first priority for Clarence and his four colleagues was to build up a sizeable force. But recruitment was going to be a tough job. How were they going to make it attractive for people to join?

This was not a job that could be undertaken by newbies off the street, so their target audience was restricted to existing soldiers in the Singapore army, which immediately narrowed down the pool of people from whom they could recruit.

At the same time, the armour divisions were also recruiting, and they had some impressive toys to show off.

They could bring tanks along to their recruitment drives, even to recruitment roadshows in the civilian heartlands. “Come and drive a tank,” they said. “Have a look inside one.” Armour had videos too, which were a very new thing in those days, and quite an attraction in themselves.

What kind of draw cards did the new commandos have to show off? A few foreign weapons. Some camouflage gear. An explosion might attract some attention, but one could hardly go around blowing things up at a recruitment drive.

There were also no major perks or incentives they could offer. The unit’s only real selling point was that this job would offer adventure and excitement. “Come and join us if you want an adventurous kind of life.”

Training the first batch of commandos

So just like that, Clarence had his first company of regular commandos.

However, they weren’t trained yet. The first thing he did was to put them through basic training. Not all of them made the grade, and some were transferred to other units.

But a good number made the cut. At the recommendation of a US advisor, this group of survivors were then sent straight off to the U.S. Ranger and Airborne courses. This would be the fastest way to train them up, was the advice. Throw them in the deep end. So off they all went.

Being a brand new unit, another big task for Clarence and his colleagues was putting together the training and exercise syllabus for the commandos.

One of the advisors called in to provide assistance felt strongly that marksmanship must be a key focus. “You must be able to shoot. One shot, one hit,” he would say. Needless to say, the men spent a lot of time at the shooting range.

Clarence’s specialty area, demolitions, was another important focus. A key skill for a commando is to be able to infiltrate an enemy position to sabotage and disable their equipment, whether that be large guns, ammunition stores, aircraft sitting on an airfield, or ships in port.

Given that regular bombs and explosives would be too heavy and cumbersome to carry on such missions, the training was focused on improvised demolitions.

Lighter options such as plastic explosives were not commonplace at this time. The men would still need to carry detonators and explosive charges with them, but they learnt how to use what they found in the field to make an effective weapon.

Unarmed combat was an interesting area of their training. Given the stealthy nature of their work, they needed to learn how to quickly and quietly disable an enemy combatant with their bare hands, before that enemy had time to reach for their weapon or arouse the attention of others nearby.

So the men worked on this intensely, and did so for the entirety of their time with the unit. At the time, the South Koreans were renowned for their expertise in martial arts – they had an entire unit focused solely on the skill.

So two instructors from there were engaged to train the Singaporeans: one from their special forces and another from their famous White Horse division.

These men introduced the Singaporeans to a military style of Tae Kwan Do in which fighting with rifles and bayonets was included with unarmed techniques. The South Koreans were heavily involved in the Vietnam War as allies of America, and one of these instructors would relate to them his experiences of real-life hand-to-hand combat in that war.

Understanding how to use a variety of foreign weapons, those likely to be used by an enemy, was another important skill the new commandos needed to learn.

Operating behind enemy lines very likely meant the soldiers needed to use weapons picked up along the way.

While most rifles and guns are fired in a similar manner, it paid to have some familiarity with different types of weapons, as during battle split-second responses could mean the difference between life and death. Hence, the men were introduced to a variety of foreign arms.

The commandos had to be good at all things: even signals and communications, Morse code, and first aid. They needed to become a self-reliant group of men.

The aim was to become masters of all trades

This was not about becoming a jack of all trades and master of none, but becoming masters of all trades. Although, in reality, they tended to focus the training so that each man became a true expert in two skill sets: Jack of all trades and master of two.

The diverse nature of the skills meant that much of the training had to be conducted by the other army units who were specialists in the specific tasks.

Some of this could be conducted in Singapore. Training for operating the 81 and 106RG mortars, for example, was conducted by the regular mortar unit. Some training had to be conducted overseas.

Men were sent in batches to places like the US for Ranger and Airborne, as well as Pathfinder courses, or to the UK for Basic Marine Commando and Airborne courses. Others were sent for advanced specialist courses such as Parachute Rigger and Special Forces training.

It was an adventurous and exciting start for the new recruits. The SAF Commando Unit was most certainly living up to its promise of adventure. And they were seeing the world. This was not a time when people travelled overseas a great deal so this perk was pretty special.

Training for infiltration was perhaps the most fun part

Given that they were to be a covert force, a lot of their training exercises involved the commandos being discretely inserted into the exercises of other divisions, such as the infantry or artillery.

This was good training for both sides. For the commandos, it provided opportunities to hone their stealthiness by conducting raids on “enemy” positions.

For the other divisions, it provided reminders that, in addition to the more obvious combatants in front of them, an enemy might also be conducting covert operations behind their own lines.

To keep the element of surprise, often the commandos were included in the exercises without the express knowledge of the other divisions.

Clarence and his men especially enjoyed this part of their training.

Much of the enjoyment came from the challenge of trying to outwit their opponents. With the fruits of their success being a chance to surprise their targeted division in sometimes – what was for them – humourous ways, their drive to succeed was real.

Though in doing so, they made a lot of enemies among their colleagues from other divisions of the army. But that was their job.

Successful "infiltrations" were a great embarrassment for other divisions

Once a year the infantry brigades would conduct a large combined exercise. During one such exercise the commandos were tasked with conducting a raid on one of the battalion headquarters.

The exercise took place on the island of Pulau Tekong, off the north eastern tip of Singapore, and the 2nd Singapore Infantry Brigade had set up their headquarters in one of the buildings there.

On the way to the target, Clarence and a small patrol of his men had to pass through a swamp. Now, a swamp might not be a piece of terrain that a commander would normally send an infantry regiment through.

Chances are that a large group like that would just get bogged down by it, putting them at great risk of being slaughtered in the water. But it could prove a very useful avenue for a small commando unit looking for a discreet route, under the cover of darkness, to approach a target.

It also turns out to be a great location to stock up on some unusual ammunition. Clarence and his men crossed the swamp, and then managed to slip unnoticed past the brigade headquarter’s security.

Then came time for the assault on the building itself. Upon storming the office, instead of simply yelling out “we’ve got you”, Clarence and his men threw mud bombs all over the place, using mud they had picked up in the swamp.

On the walls, on the desks, on the paperwork, and at the people themselves. Naturally, the brigade commander was not very happy. But the commandos had done their job.

And then there was the commanding officer of 3 SIB who was so proud of the below-ground headquarters that he had ordered dug out using excavators at the beginning of another exercise.

The temptation to undermine his efforts was too great for Clarence’s chaps. During that exercise, the “enemy” officers and NCOs operating in that subterranean bunker were seen running out onto open ground to escape the smoke from the smoke-grenades thrown inside by the raiding commandos.

Yes, Clarence and his men had a lot of fun during these exercises. They certainly got up to a lot of mischief and made a lot of “enemies”.

The recruitment of NSFs began when growth was not as fast as expected

By 1973, the recruitment of soldiers into the commandos was not as fast as Clarence and his colleagues wanted. Their policy to recruit only from within the army was impeding their growth. They needed a boost.

So Dr Goh Keng Swee and the Ministry of Defence stepped in, making a policy decision to allow the commandos to start taking in National Servicemen.

To enable them to get these fresh recruits up to the fitness and skill levels they required more quickly, the commandos became the first unit in the Singapore army to independently handle their own basic military training.

Up until then all new recruits, regardless of which division they would eventually serve with, underwent the same basic training course.

Given the nature of their job, commandos needed to be trained to a more rigorous and exacting standard.

So if they were going to take in men straight from civilian life then it was key that they had control over this training from the very beginning.

In fact, Clarence and his colleagues also gained control of the recruitment and selection of their new recruits, further ensuring that they had the right men for the job.

While it was not as ideal as having a unit that was made up completely of regulars, at least they had these NSmen for two and a half years, which was plenty of time to train them up and mould them.

With the advent of recruitment via the National Service route, the numbers in the unit began to grow significantly.

The advisor assigned to help the commandos in the early days of their formation was an interesting guy, and a key ally for the commandos in these early days. A hard and strict man who pushed them accordingly, he was an older guy who had seen fighting, and had been toughened by it.

And he was a man that Clarence would come to respect immensely. Not the type of advisor who would sit back and watch his soldiers training from a distance, he was always with them in the thick of action.

Up the hills, in the jungles, and everywhere else around Singapore. Wherever their training took them, he followed.

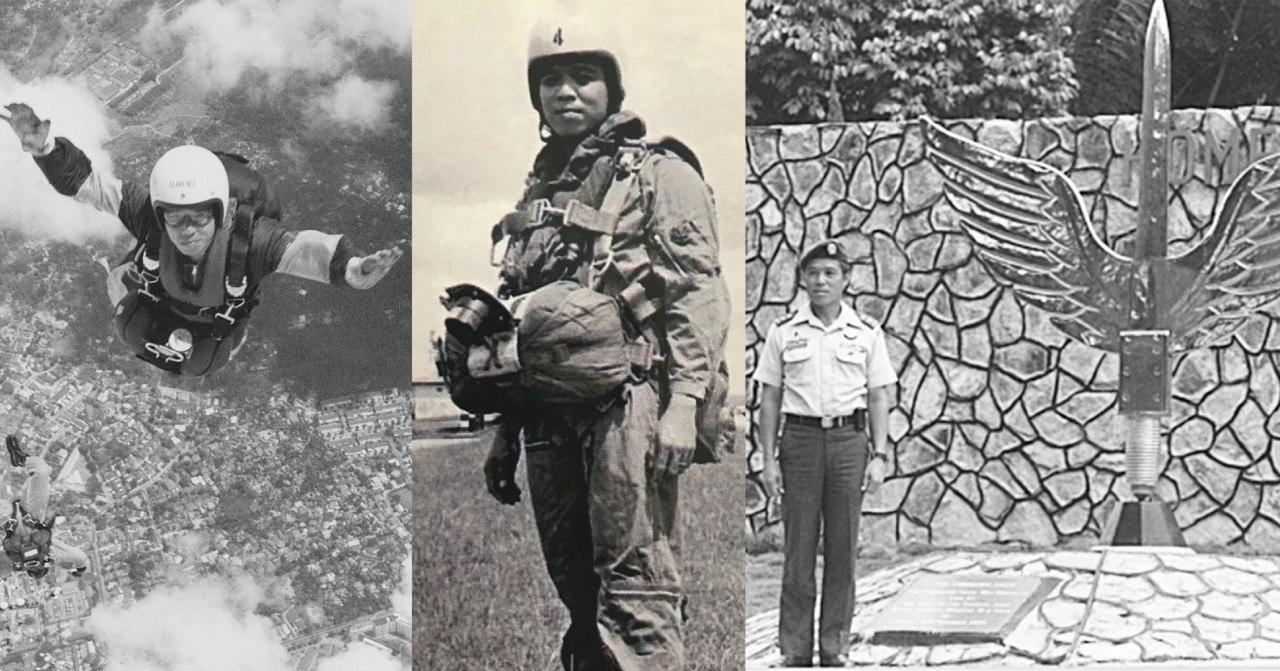

Top photos courtesy of the author Thomas Squire and family

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.