Alaric Tan's first taste of meth was surreal.

"It hit my brain like a bomb. I just immediately perked up. I was extremely alert, just... incredibly aware of everything that was happening around me. It gave me a sense of confidence and assurance that was extremely unreal."

"I felt like I could do anything in the world," says the 41-year-old, who today runs The Greenhouse, a substance recovery centre for marginalised communities.

Operational for close to three years now, the recovery centre occupies a nondescript two-storey brick house in central Singapore.

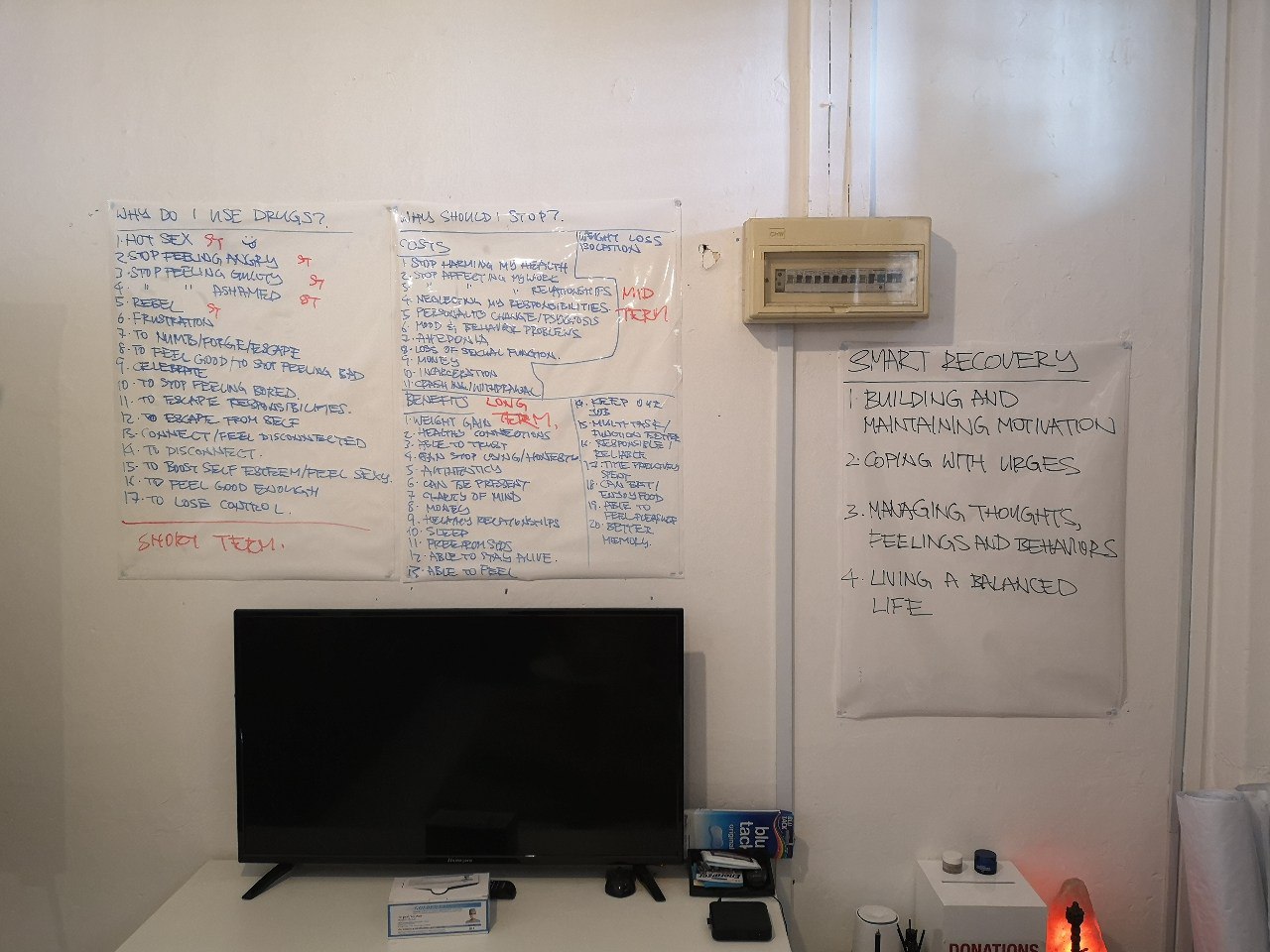

Its spartan interiors are furnished with just the barest essentials — a couch and a television occupy the room we're in. A poster exhorts the dangers of drugs — health problems, relationship breakdowns, and a huge drain on finances, just to name a few.

It's a litany of difficulties Tan is acutely familiar with, having been through a 20-year journey of drug abuse, addiction, devastation, and finally, redemption.

Inside The Greenhouse: Posters like these line the walls, reminding clients that the long term consequences of drugs far outweigh the short term gains. Image by Joshua Lee.

Inside The Greenhouse: Posters like these line the walls, reminding clients that the long term consequences of drugs far outweigh the short term gains. Image by Joshua Lee.

First introduced to Ecstasy when he was 21

Tan was first introduced to drugs, specifically half an Ecstasy (MDMA) tablet, on his 21st birthday in a Bangkok gay club.

If it wasn't for a close friend who assured him that half a tablet wasn't a big deal, the self-professed "prim and proper" young man wouldn't have even given it a second look.

The effects, he says, were life-changing.

"I've always walked around with the sense that there's something wrong with me, that I should be ashamed of myself, that I was never good enough. All those feelings just completely melted away the moment the effects hit me."

The effects of Ecstasy — an overwhelming surge in confidence and empathy — were extremely intoxicating, even more so for someone who had been beating himself up for years over his sexuality.

Tan cannot recall when he started identifying as a homosexual, but remembers his parents — a civil servant and a secretary — sending him for a 12-month-long Christian conversion therapy programme (a mix of pseudoscience, prayer, and worship, he says) when he was 16.

Subsequently, he had to attend weekly sessions with a psychologist for his severe social anxiety and depression which, ironically, was brought on by the attempt to "pray the gay away".

And while Tan's conversion therapy was a spectacular failure, it taught him something:

"Unless I was exactly what (my parents) wanted me to be, it's not okay. I felt very rejected."

A dog that had been beaten — that's what Tan likens his past self to, crippled by anxiety and self-loathing.

"When people try to get close to them, they will run away because they're afraid that they're going to be hit with a stick. I did not feel safe," he says, as he fidgets with his fingers.

It's clear that Tan's anxiety still sticks with him, but he recognises and acknowledges it — a shadow that he has learned to live with and embrace ("I think that it makes me relatable.").

From "successful user" to addiction

At first, Tan's drug use was restricted to the occasional Ecstasy, Marijuana and Ketamine, which he would only indulge in when he was in Bangkok.

He was, by his definition, a "successful user" who was very particular about how much and how often he used.

"I could party all weekend and still drive to work on Monday and chair meetings. I could run into roadblocks and have a chat with the police officer who suspected nothing."

But as with all addictions, his usage grew steadily from four times a year to once a month, and then twice a week.

A drug user builds tolerance to the drugs over time so he would require more and more just to reach the same high, explains Tan.

Even then, it was a "manageable" habit, he says, right up to the point he started taking methamphetamine ("a totally different kettle of fish altogether").

Even before he started using meth, Tan says he was well aware of the dangers associated with this incredibly addictive drug.

But in 2008, he was in between jobs and, overwhelmed by uncertainty, he took the opportunity offered by a close friend to give meth a try.

"I got hooked on it really, really fast. I went from being an occasional user to a daily user within a matter of months."

Aside from meth, Tan was also addicted to GHB (Gamma-hydroxybutyrate) and had to depend on an hourly dosage of 1ml just to go about his day.

"I physically could not get out of bed unless I took the drugs. So when I woke up I had to smoke meth and take GHB. It took me like, an hour to put myself in the right frame of mind to crawl out of bed."

Tan's addiction was so severe that he was compelled to bring his drugs around with him. It was dangerous — drug possession can earn you a 10-year jail sentence in Singapore — but Tan didn't care.

Without his regular doses, his mood would crash and he would quickly find himself overwhelmed by paranoia, fear, and anxiety.

"I would think people were watching me, following me. I would think that people were out to harm me," he says. Once, he passed out from a GHB overdose in public and had to be sent home by (thankfully) his partner.

What was once a silver bullet for his shame and anxiety became a crutch that he hated.

Despite multiple attempts to quit — through counselling and even a detox programme in Chiang Mai — years of addiction made it near impossible. He even managed to convinced himself that he didn't really want to kick the habit.

A lightbulb moment

It all came crashing down when he was arrested in February 2016 and did a six-month stint at Singapore's Drug Rehabilitation Centre in Changi Prison. Being forced to be clean for six months gave him hope that recovery was possible.

Later in October, Tan joined a 12-step recovery programme that had a peer support component. That would turn out to be the missing piece in his recovery process.

But of course, it wasn't that easy. After his release from prison, he suffered three relapses. The third was especially severe, but he says it was a turning point for him.

"I used drugs for a week without eating or sleeping and I went to a recovery meeting and I was high, I was paranoid, I was sweating and ashamed. The strangest thing happened. I realised that not a single person in the room judged me. They understood what I was going through. I felt safe for the first time."

It was a lightbulb moment for Tan.

Being with people who who have been through the same traumas and are working through the same issues is essential for recovery, he says.

"When we can see for ourselves that others are getting better, it's living proof that recovery is possible."

Within eight months, Tan managed to stop using drugs completely. Even the cravings went away.

"No one aspires to be a drug addict"

Conventional wisdom dictates that people turn to drugs because it makes them feel good, but Tan disagrees.

"What's so not good about our lives that we want to feel good so much that we would endanger everything else? We think we want to feel good but no, we just want to stop feeling bad."

Addiction, says Tan, is a mental health issue and a coping mechanism. "No one aspires to be a drug addict."

Being in recovery has allowed him to see that his years of drug abuse was an attempt to handle (rather unsuccessfully) his deep unhappiness and pain.

Gay men, says Tan, are highly susceptible to drug use, be it for personal use or sex, because it helps them get over various inhibitions, both conscious and subconscious:

"Shame over our bodies, the fact that we're not quite okay about being gay, the fact that we feel like a failure, the fact that we don't feel that we're allowed to be authentic, that people judge us, that we are criminals, all of these things are there."

In fact, Tan says everyone who comes to him at The Greenhouse point to at least one of these triggers of their addiction: broken or dysfunctional families, physical, mental, emotional or sexual abuse, guilt and shame over sexual orientation, bullying and discrimination in schools, and internalised homophobia.

Paying it forward... for free

It was Tan's personal recovery process that prompted him to "pay it forward" by starting his own recovery centre.

In July 2017, he did just that, running substance recovery programmes for marginalised communities, including LGBT folks.

The stories he heard from his clients have reinforced his conviction that his recovery programme is all the more needed for this vulnerable community.

He shares one story of a client whose father pushed him down the stairs when he found out he — a recovering drug addict — was a homosexual.

"I don't feel that people who have never had such an experience have the right to say that we use drugs for a good time," says Tan resolutely. "I don't think they understand what they're talking about."

Inside The Greenhouse: A mini garden sits in the recovery centre, maintain by one of its clients. Image by Joshua Lee.

Inside The Greenhouse: A mini garden sits in the recovery centre, maintain by one of its clients. Image by Joshua Lee.

Clients who come to The Greenhouse are usually first assessed to establish their usage pattern, before Tan helps them explore the cause of their addiction and come up with a recovery plan.

Over its two and a half years of operations, the number of people Tan helps has grown from 10 to 150.

The number of people who are stepping forward to seek help has also grown from two to three per month to eight in January 2020. Testimonials from clients laud the centre as a safe space that helps them stay grounded and supported in their recovery journey.

What's more remarkable is that the service Tan provides is completely free — it runs on his own savings, donations from clients, as well as funds raised by the public. "We don't want to add an additional impediment to those want to seek help," he says.

Tan admits that it is difficult to raise funds from the public because his beneficiaries — substance abusers who are LGBT, HIV-positive, and even victims of sexual assault — tend to be "controversial" in many people's eyes.

But of course, he notes, it is for this very reason that this group needs support.

"It's an upward task. We put together campaigns, we spread the word, we have a lot of testimonials from people who have done very well. But it's really hard to bring in the money to keep the centre going. There's a lot of stigma and a lot of education that need to be done."

Despite this, Tan is plowing on for his cause, not just for the people he continues to help but for himself as well.

Today, he is two and a half years clean, and has a thriving relationship with his mother. It's a stage he never thought he would arrive at at just four years ago.

"I thought life would still be extremely challenging to live but I'm much less anxious, stressed, and unhappy. I heard that the third year will be different. I can't wait."

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or making the world a better place in their own small way, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Joshua Lee. Quotes were edited for clarity.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.