Beating the Odds Together, edited by Mattia Tomba, is a collection of essays which commemorates the 50 years of diplomatic relations between Singapore and Israel.

Here, we reproduce an excerpt from an essay contributed by Peter Ho, titled "A Mexican Fandango with a Poisonous Shrimp", where he described Israel's military contributions in developing Singapore as a poisonous shrimp during a time of great uncertainty.

Ho headed Singapore's civil service from 2005 to 2010, and was also Permanent Secretary (Defence) from 2000 to 2004. He is currently the Senior Advisor to the Centre for Strategic Futures.

Beating the Odds Together is published by World Scientific and you can get a copy of it here.

***

By Peter Ho

Bilateral relations between the two nations had to be discreet

The defence ties between Singapore and Israel are almost as old as independent Singapore. Arguably, this unusual partnership was the foundation upon which the larger bilateral relationship has been built.

But for many years, it was shrouded in secrecy.

To this day, little has been written about the Singapore–Israel defence relationship despite its significance. This reticence is derived from the reality of Singapore’s neighbourhood.

The state visit of then-Israeli President Chaim Herzog to Singapore in 1986 sparked demonstrations — and political remonstrations — in both Malaysia and Indonesia.

This experience would have reinforced in the minds of policymakers in Singapore that the bilateral relationship with Israel — above all, the sensitive defence relationship — had to be managed discreetly in order to preserve and protect the substance.

The Israelis were referred to as "Mexicans"

So all these years, while Singapore has not denied that it has close defence links with Israel, at the same time, it has eschewed speaking openly about them and revealed few details.

Indeed, this low-key approach was adopted when the first team of military advisers from the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) visited Singapore in 1965, soon after Singapore’s separation from Malaysia. To disguise their presence, they were famously described as “Mexicans”.

In his memoirs, Lee Kuan Yew remarked that they looked “swarthy enough”, presumably because of their tough life in training and operations under the hot Levantine sun.

Since then, Singapore’s links with the Israeli defence establishment have grown in breadth and depth. A close relationship between two very different systems emerged.

If the Israelis were “Mexicans”, then perhaps the active and lively way that Singapore engaged Israel on the defence front could be described as a Mexican fandango.

The newly independent Singapore faced an existential crisis

To understand the roots of this Mexican fandango, we need to go back to 1965, when Singapore separated from Malaysia. Few then gave Singapore much chance of surviving on its own, let alone succeeding.

With the unexpected and unwanted divorce, Singapore lost its economic hinterland in Malaysia. A communist insurgency was barely over.

President Soekarno’s Indonesia was still waging an armed confrontation — Konfrontasi— against the “neo- colonialist” creation of Malaysia, and Singapore was not spared. The Vietnam War was growing in intensity.

These were not propitious beginnings for the newly independent state of Singapore. It was a very parlous situation that convinced the Singaporean leadership of the imperative to rapidly build up a credible — and independent — defence capability.

It was an existential priority from day one.

Singapore had to become a poisonous shrimp

It did not take rocket science to figure out that Singapore’s defences were in a bad state. At independence, Singapore had only two under-strength infantry battalions, with more than half of the soldiers Malaysians.

There was an ageing wooden gunboat, and not a single aircraft — nothing that could pass for either a navy or an air force.

Although the British maintained a large military presence in Singapore and Malaysia, political pressure was growing back in London to cut its military presence east of the Suez. Singapore had to assume that the British military presence would be withdrawn at some point in time.

Singapore had to be able to defend itself.

Reflecting this determination, Lee said in 1966 that in a world where the big fish eat small fish and the small fish eat shrimp, Singapore must become a poisonous shrimp.

It may have been bravado then, but the poisonous shrimp metaphor staked out the beginnings of a defence strategy of deterrence that would eventually be embraced by Singapore. So, the task was clear-cut, yet overwhelming — to build an army virtually from scratch, and quickly.

Goh Keng Swee was tasked to build the SAF from scratch

Dr Goh Keng Swee, then Finance Minister, volunteered to lead the effort, although Lee wryly noted that all Goh knew of military matters had been learnt as a corporal in the British-led Singapore Volunteer Corps until it surrendered to the Japanese in February 1942.

A small team under the leadership of Goh was hastily assembled to form the new Ministry of Interior and Defence, combining into one ministry what is today divided into the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Home Affairs.

With a small population and limited resources, Singapore could not afford a large professional army. Initially, the government tried to get round the problem of cost by establishing a part-time volunteer “territorial” army.

It created the People’s Defence Force (PDF) soon after independence.

But, truth be told, the government was not confident of getting enough volunteers,especially as the majority Chinese population had a cultural aversion to service in the military. It was not a sustainable model.

The Brown Book

Goh had already been impressed by Israel’s defence system during his first visit to the country in January 1959, when he was Minister for Finance.

Israel is a small country like Singapore, but located in a hostile region. It had been among the first to recognise Singapore.

Ze’evi was then the IDF’s Deputy Head of the Operations Directorate. He had the intriguing nickname “Gandhi”. Ze’evi was despatched to Singapore in October 1965 to meet Goh under conditions of great secrecy.

During his visit to Singapore, ever the military professional, Ze’evi travelled incognito by taxi around Singapore to familiarise himself with the terrain and the ground conditions.

Upon his return to Tel Aviv, he assembled his team, which included Meir Amit, then director of Mossad. They developed a masterplan for the build-up of the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF).

This masterplan was called The Brown Book. Ze’evi had it ready within a month, and translated it into English two months later.

The Brown Book was broad in scope. It covered strategy and doctrine. But at its core was the fundamental assessment that the only viable solution for Singapore was to build a citizen army of conscripts, trained and led by a small regular force.

To this end, it proposed the establishment of an “Officer Training School” to produce this corps of professional leaders. Citizen-soldiers would form the backbone of the citizen army, so that in an emergency, the entire nation could be mobilised under arms.

Israeli advisors were here to advise, not to command

The Brown Book detailed a masterplan to put this concept into effect. It envisaged, among other things,the army’s expansion to 12 battalions within a decade, an objective that could only be achieved through conscription

Soon after, the Singapore and Israeli governments signed a one-page agreement, which stated simply that Israel would provide defence advisers to Singapore. They would be given their equivalent Israeli salaries, plus board and lodging.

Indeed, these terms proved to be very generous on Israel’s part, as Singapore benefited enormously from the priceless advice of the Israelis.

A small group of seven Israeli advisers — or “Mexicans”, if you will — led by Colonel Yaakov “Jack” Elazari arrived in Singapore in November 1965. Prior to their departure, they had met Rabin, who told the team:

“I want you to remember several things. One, we are not going to turn Singapore into an Israeli colony. Your task is to teach them the military profession, to put them on their legs so they can run their own army. Your success will be if at a certain stage they will be able to take the wheel and run the army by themselves. Second, you are not going there in order to command them but to advise them. And third, you are not arms merchants. When you recommend items to procure, use the purest professional military judgment. I want total disregard of their decision as to whether to buy here or elsewhere.”

Pasir Laba was selected as the site for the first Officer Training School

When Elazari landed in Singapore, like Ze’evi before him, he too familiarised himself with the terrain. Driving himself around the island, he kept an eye out for potential sites for the Officer Training School that had been proposed in The Brown Book.

He eventually selected Pasir Laba, having earlier ruled out two islands north-east of the main island: Pulau Ubin and Pulau Tekong.

Elazari made his recommendations to Goh. They were accepted, and led to the establishment of the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute, or SAFTI.

The bulldozers quickly moved into Pasir Laba. Within a year, the construction of SAFTI was completed, based on plans from the Israeli Engineering Corps. It was an impressive feat, even if SAFTI was very basic in design and facilities, driven by the urgency to get the SAF up and running.

With SAFTI, the Israeli advisers were truly ready for business. Their first priority was to build up a pool of Singaporean instructors and commanders. In the parlance, they “trained the trainers”.

They insisted from the very start that the Singaporean officers were to learn from them so that they could take over as instructors as soon as possible.

Every job they did was understudied by a Singaporean counterpart, from platoon commanders to company commanders, right up to the top position of director general staff. They even had the officer cadets write the instructional material.

Lee observed that while the Americans had sent about 3,000 to 6,000 men in the first batch of military advisers to help President Ngo Dinh Diem build up the South Vietnamese army, the Israelis sent only 18 officers.

First batch of cadets completed their training in July 1967

On 16 July 1967, Ze’evi, together with the other Israeli advisers, was invited by Goh to the commissioning parade of the first batch of 117 Singapore officer cadets who had completed their training at SAFTI.

On Goh’s instruction, they came in their IDF military uniforms. Goh then explained their presence. He said:

“You have heard of the Six Day War, which commenced on 5 June. Seated here with me today are part of the Israeli mission which has been advising us on how to build an army.”

The “Mexicans” had been unmasked as Israelis. This revelation signalled that Singapore was now ready to deal with any military threat.

With this disclosure coming after the Six Day War in June 1967, the deterrence message was clear: that since the SAF had been designed and trained by the Israelis, it would be a force to be reckoned with.

Goh was staking out the parameters of the poisonous shrimp strategy.

S'pore's first tanks were unveiled on National Day in 1969

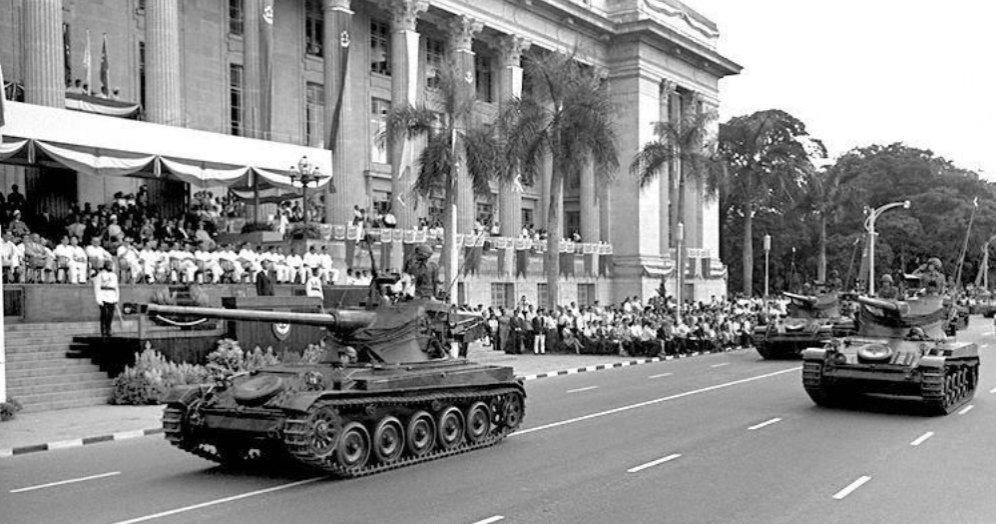

However, it was not only through training that Singapore’s poisonous shrimp strategy was being realised with the assistance of Israel. In great secrecy, Singapore purchased 72 AMX-13 light tanks from IDF surplus.

To support this acquisition, the IDF trained the pioneer team of 36 SAF armour officers in its own armour school back in Israel, just as it had also begun training other military vocationalists from Singapore.

Then the bombshell was dropped. On Singapore’s National Day on 9 August 1969, 30 of these AMX-13 tanks rolled past the reviewing stand at the Padang. With understatement, Lee wrote: “it had a dramatic effect ...”

While some may have had reservations over the relevance of Israel’s military experience to Singapore’s tropical environment, there is no doubt that the IDF has been one of the most important influences on the development of the SAF.

The “Mexicans” played a key role in the early years of the SAF, helping to establish its National Service system, its training system and its military organisation.

Top image from NAS.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.