On the morning of February 9, 1992, many Singaporeans woke up to the following headline in their newspapers:

"Reject liberal social, economic policies: Mr Lee"

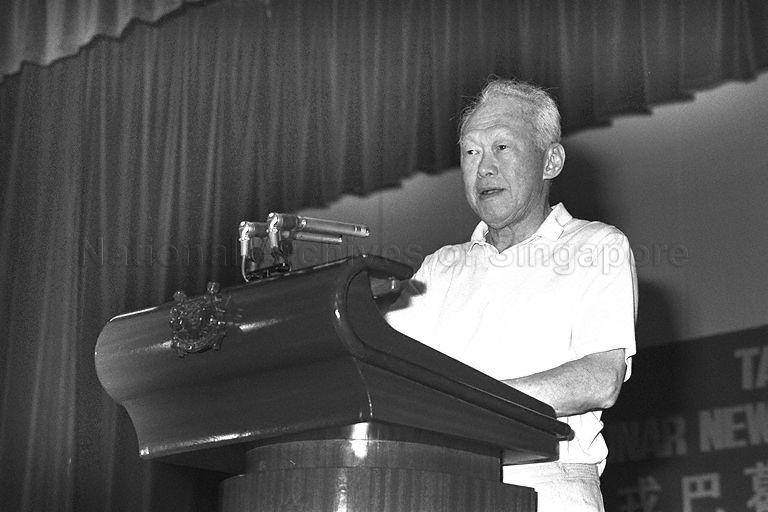

The story was straightforward enough, covering Singapore's founding father and former prime minister's (at that time two years out of the job) Chinese New Year speech.

Lee Kuan Yew speaking at the Tanjong Pagar GRC Lunar New Year get-together, circa 1992. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Lee Kuan Yew speaking at the Tanjong Pagar GRC Lunar New Year get-together, circa 1992. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Nestled within the late Lee Kuan Yew's speech, and in the printed words of The Sunday Times, was a public chastisement of a "young liberal sociologist in NUS (National University of Singapore)".

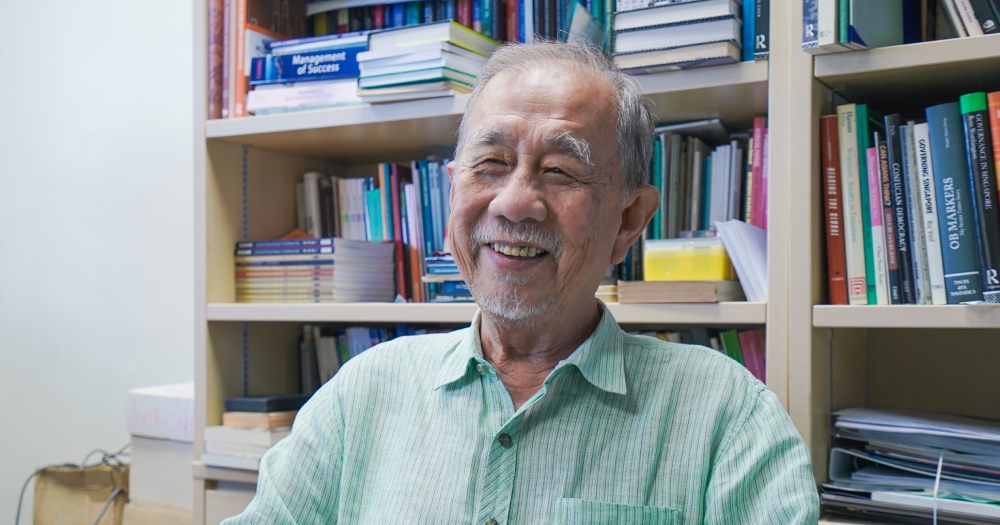

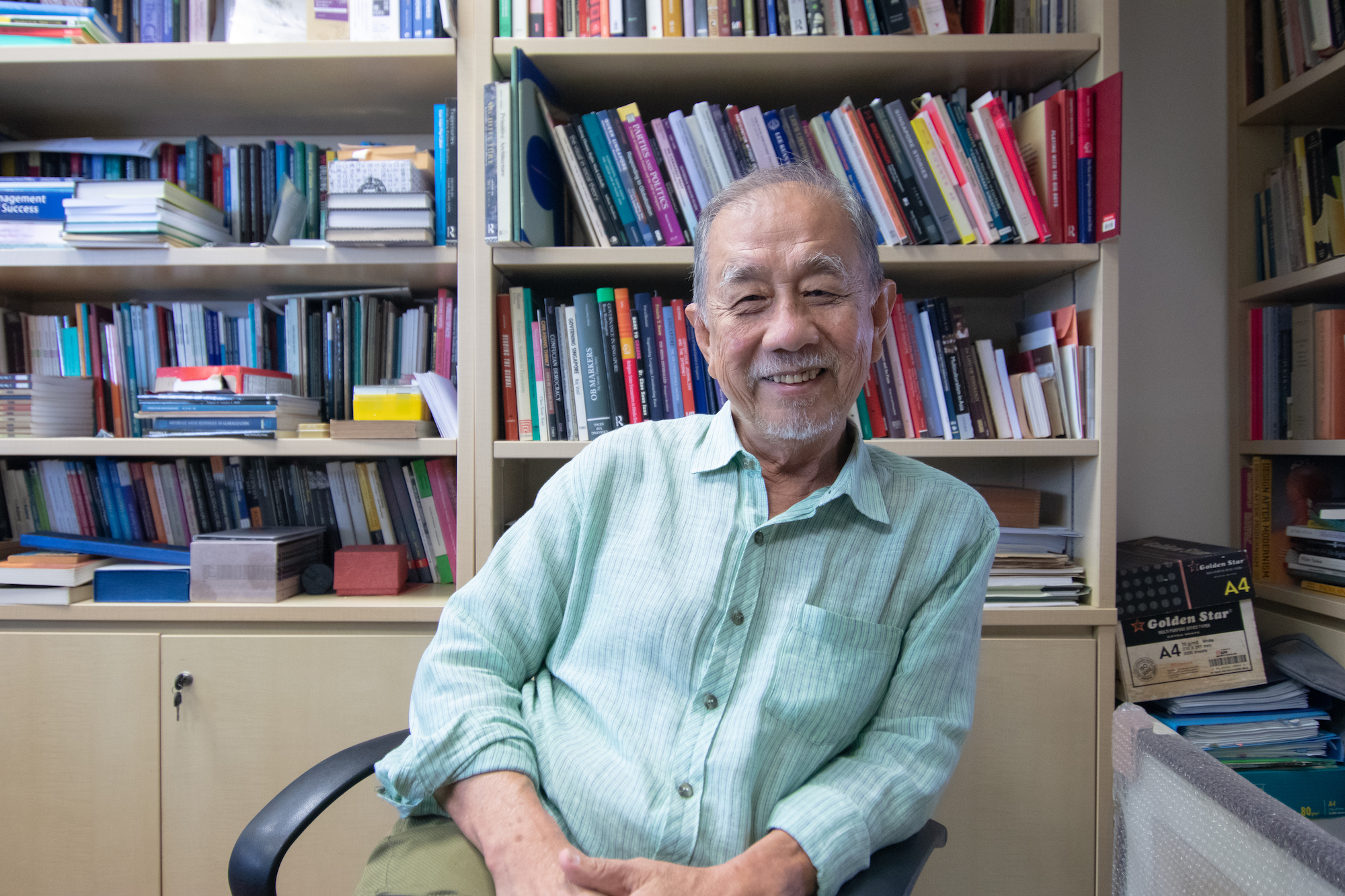

28 years on, I find myself sitting across from Professor Chua Beng Huat, the man widely believed to have been the target of Lee's scolding.

Recounting that episode to me, the now-73-year-old Chua says it stemmed from a column he wrote that was published in The Straits Times in the year preceding Lee's Chinese new year speech.

Chua had been presented with data that showed about 65 per cent of university students in Singapore came from public housing.

"That's actually good data because it shows that there's upward mobility. But it's only half the table.

So I said, yeah I could see (the upward mobility), but the point is that 35 per cent of the university students come from private housing, right? There was only 10 or 12 per cent of people living in private housing, which means that the family circumstance is contributing greatly to upward mobility."

"Lee Kuan Yew got very upset with what I said," speculates Chua. "I was showing a class difference that was denied, that was kind of not talked about."

Evident from the fact that Chua is telling me all this from the confines of his office in NUS's Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, he survived that encounter with his career intact.

It was, however, one of a few incidents that gave rise to an academic bestowing Chua the title of "most publicly scolded sociologist in the country" — incidentally the most badass appellation a professor in Singapore can attain.

These days, Chua is known mostly by university students majoring in the social sciences as a veteran academic whose journal articles are sure to be part of any reading list for a class on Singapore.

Yet there was a time gone by when he was known more widely by Singaporeans as a newspaper columnist, whose appearances in The Straits Times demonstrated analysis that was penetrative, insightful, and often critical.

"The funniest joke is when my brother's accountant was one day having breakfast with him. He said: 'Do you read this guy Chua Beng Huat?' and my brother just said: 'Yeah, so what about him?' (The accountant) says 'one day he's going to be arrested for what he says in the papers!'"

"Nothing in my early life has any inclination that I would be a university professor"

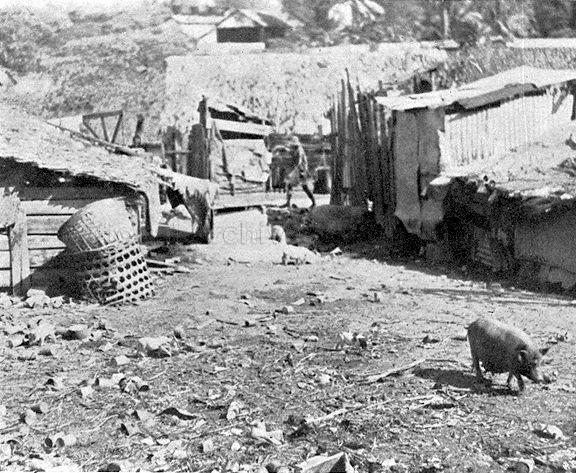

Chua grew up the second-youngest of eight siblings amongst attap houses in what he describes as the "urban kampong" of Bukit Ho Swee.

"Every time you see picture of those places it's always horrible. But actually we were the business family in Bukit Ho Swee. My father had his own lorry business so our income comes from that side. But also my mother had a very big provision shop. So we were not your typical sort of your imagined poor Bukit Ho Swee family. Actually we had a huge house."

Bukit Ho Swee Estate and the attap houses typical of the area, circa 1947. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Bukit Ho Swee Estate and the attap houses typical of the area, circa 1947. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

That relative financial security also afforded Chua the privilege of attending two different primary schools at the same time — one in the morning and one in the afternoon.

It might sound like every child's nightmare, but not so for Chua the primary school student:

"My parents never forced me; I sort of did it partly out of ego, partly out of pride that I could do it."

You might think that going to school twice a day would make one a good student, but once again Chua bucked this trend.

He describes his pre-university self as being distinctly average in academic endeavours — at least one of his teachers, he recalls, predicted he would not pass his O-Levels.

"Nothing in my early life has any inclination that I would be a university professor. Absolutely nothing.

In A-Levels, my grades were miserable enough. But more importantly, by the time I'd finished my A-Levels, at that time, 1967, the PAP government was actually targeting left-wing students a lot."

Back then, students who wanted to receive tertiary education needed to apply for a Certificate of Suitability — a policy introduced in 1964 to prevent suspected communists from infiltrating institutions of higher learning.

The policy regime was eventually abolished in 1978, but not before it had deemed Chua unsuitable for local university education.

Going to Canada and getting political

While it would have been easy for Chua to end his education at that point (none of his older siblings had gone onto university and instead worked in their parents' businesses anyway), he started applying for universities overseas because he "kind of liked learning".

By September 1966, he found himself in the small Canadian town of Wolfville, Nova Scotia, pursuing a degree in Biology and Chemistry at Acadia University.

Chua completed it in 1969, cramming what was originally a four-year programme into three years (how very Singaporean of him), but wasn't sure what to do with himself afterwards.

"Towards the end, I actually applied to the University of British Columbia, in bio-sciences. I actually lined up a PhD scholarship to do neurophysiology. But by then I had decided I wasn't going to be a scientist."

He eventually drifted into a Masters programme in Environmental Studies at Toronto's York University.

However, apart from his studies in science, university education gave Chua more and more exposure to issues surrounding social causes and politics. It was a period of his life that in his own words firmed up his "sense of post-colonial sentiments".

"The late '60s were the years where there was a global student revolution right? So throughout the '60s, on campus I was fairly politically-active in terms of student activism, organising forums and stuff like that, going to a lot of anti-Vietnam sit-ins and stuff like that."

His burgeoning interest in the arts and social sciences resulted in Chua quitting his environmental studies Masters after a year and switching disciplines to work on a PhD in Sociology.

"My first job came quite serendipitously. I was finishing my PhD and another friend who had gone two or three years ahead of me was already teaching at this undergrad college called Trent University. We met at a conference and I said: 'I guess I should start looking for work'. He said: 'Yeah, we're looking for somebody'."

That seemingly casual conversation turned into a seven-year teaching job at Trent University, with Chua describing the process with a chuckle — "I ended up being an academic without looking for it".

"I was very uncomfortable all the time"

Perhaps it was these years of meandering through life in Canada — from university to university — that helped solidify Chua's conviction that he needed to return home.

"This is funny to say, but (Canada) is too easy and you lack motivation. It's very easy to do the minimum and have a decent life. It's hard to push yourself.

I was very uncomfortable all the time."

Eager to explore his options, Chua, who was in the early 1980s back in Singapore on a sabbatical, saw a job advert in The Straits Times.

The Housing Development Board (HDB) was looking for a sociologist, an opportunity unique enough to pique his interest.

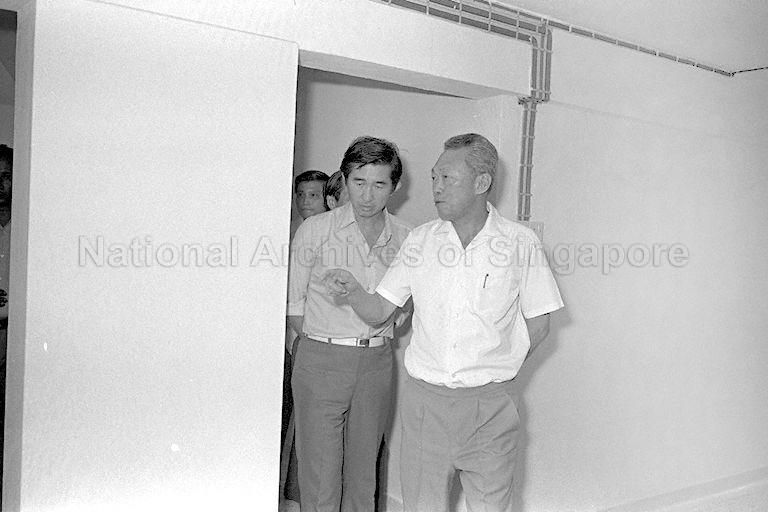

He arranged for a meeting with HDB's then-CEO Liu Thai-Ker (whose very fascinating life, by the way, you can read about here and here).

"Why don't you get some from the (local) university?" Chua remembers asking.

"I know all of them," he quotes Liu. "I know what kind of work they do. It doesn't quite fit what I want."

"So what do you want from a sociologist?" pressed Chua, curious to know if he would fit what Liu needed.

"I don't know," he recalls Liu responding, "but I know I need one."

Liu Thai Ker (L) with Lee Kuan Yew, circa 1980. Photo by Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Liu Thai Ker (L) with Lee Kuan Yew, circa 1980. Photo by Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Chua says Liu explained that he was building housing for the whole nation, and needed to know what life was like in the housing estates. Chua, should he be given the job, would be the director of the social research unit — basically the man in charge of finding out how people were living in their newly-built estates.

The sociologist left some essays with Liu, who was suitably impressed, arranging for Chua — the only candidate for the job — to be interviewed by a panel at the Public Service Commission.

Working at HDB

In 1982, Chua negotiated with Trent University to let him take another year off, so he could commence his research with HDB. By 1983, he was commuting back and forth between Canada and Singapore, before he eventually left the university to go full-time with HDB halfway through 1984.

"I was translating information into useful knowledge. Of course, you lose academic freedom because you're now working for the government inside the bureaucracy but there's a great sense of the impact of the work."

One project involved the upgrading of electrical points that residents had in the kitchen.

"This was already in the early '80s, and the HDB was still providing electrical outlets in the 1970s standards. I went to see the CEO and I said to him, 'One day HDB is going to be responsible for the blackout for the whole island.'

He said, 'What nonsense are you talking about?'

I said, 'Do you realise how many appliances are in the kitchen by now?' Because there's a freezer, electrical kettle, electrical rice cooker, you know? I said, 'Not only that, but all of those are turned on between five and seven o'clock.'"

At that time, HDB flats only had two electrical points in the kitchen, pushing residents to DIY extensions for their growing number of staple appliances.

But his boss was a man who required proof. Chua took five researchers with him to a few HDB blocks. They went into kitchens and noted how many appliances each household used.

"We came back and showed him the numbers. He immediately called in the electrical engineers and showed them what was happening and what they had to do."

"I actually liked the work a lot," says Chua. "It was quite upsetting when I got fired."

Getting scolded. Again.

Lest you forget, this isn't an interview with an obedient civil servant. No, I was talking to "most publicly scolded sociologist in the country".

According to Chua, it was an academic essay that he had written and submitted for publishing before he worked at HDB that cost him his job there.

The essay, which was critical of the government's pragmatism, was published right after Chua went full-time at HDB and within half a year, he found himself once again looking for work.

"Liu Thai-Ker asked me where do I want to work. I said I could go to the university or go to The Straits Times. He said, 'You better not be a journalist, you better go to the university.'

Because, he said, '(at The Straits Times) you'd just be another sh*t disturber writing public affairs stuff'."

Chua heeded Liu's advice. Sort of.

While he worked as faculty at NUS, editors of The Straits Times often approached him for comments on an issue, or to write columns.

Apart from his public scolding from Lee Kuan Yew, one other memorable run-in with the government saw Chua mentioned by four different politicians in a 1993 sitting of Parliament.

"The government did a survey of the poor because Chee Soon Juan was complaining about poverty and all that. When the report came out, it was fairly glossy (saying) that things were not bad — blah blah. The Straits Times called me and asked me what I thought.

I basically said, 'You shouldn't be asking me because I'm in the financial position which is not affected by inflation, or (economic) downturn, or anything like that. You should go and ask the poor what they think of the report and I don't think they will agree with the report'."

That triggered a parliamentary chiding from former cabinet minister Lim Boon Heng — who happened to be in charge of the committee overseeing the report — over his supposed disagreement.

Insisting that his Cost Review Committee had an adequate understanding of "everyday realities", Lim told Parliament:

"So the question to Mr Chua really is this: Mr Chua is not poor. What role should he, as an upper-income member of the community, play to help the poor he sympathises with?"

S. Dhanabalan, then the Minister for Trade and Industry, also admonished Chua, saying that the professor's problem (and the problem of other critics) was that "you want to hold to a position and you are saying, 'Please, do not confuse my prejudices with facts'."

Lim Boon Heng (L) and S. Dhanabalan (R), circa 1993. Image from the Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Lim Boon Heng (L) and S. Dhanabalan (R), circa 1993. Image from the Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

"In Parliament, my name came up four times," Chua said with the slight twinkle of a mischievous grin.

"Dhanabalan and Lim Boon Heng were against me. Tan Cheng Bock (then still a PAP Member of Parliament) and Chiam See Tong defended me in parliament, over the same issue."

Earning respect

Though he was upset at being singled out, it's fortunate that Chua's two most public clashes with the government are as dramatic as it got — a far cry from the prediction his brother's accountant had made.

His endurance as a critical public figure is also no doubt due to his insistence on being balanced.

"If you’re a Singaporean and you’re someone who is an academic and someone who is intellectually inclined, you cannot deny the positive things that have happened in the country. And therefore, in recognition of that, the criticism must take that into account.

Foreigners writing about Singapore can always focus exclusively on authoritarianism, changing political structure but I think as a Singaporean it’s not that simple. The productivity of the nation, the way it is governed has to be taken into consideration. Then after that, where it is less than desirable becomes the point of commentary. And it can be quite critical commentary, can be quite sharp."

And sharp he is.

Instead of shying away from potential trouble, Chua feels that the role of a public intellectual demands honesty.

"Staying quiet is one thing, but if you want to make a public statement then you need to be able to live with yourself. Otherwise don't say anything.

You either actually say why there is injustice and why it is not acceptable or you don't say anything. If you say half-truths, right, you can't face yourself. Because other people don't know but you know. You know you have not said everything that needs to be said."

It's that honesty, as Chua looks back on his time in the public eye (reluctantly, I might add: "it's a little too self-aggrandising", he tells me), that brings the ageing sociologist the most pride.

"I think the most important thing was that I was seen as a critical person at the point at which being critical was deemed as dangerous.

Low Thia Khiang actually told me, he said 'Hey, you got a lot of respect from us for the fact that in the '90s you were willing to speak up when nobody was.'"

His style of fair and honest criticism has perhaps also earned Chua respect from places one might least expect as well.

"If you are balanced and pointing out things that really need fixing and don't personalise the issue but actually deal with it and are not self-interested — that's really important, that it's really not in it for yourself, you're not out to make a name for yourself so everybody knows who you are — you get a grudging respect from the government. They may not like you but they respect what you have to say."

Chua believes this is best illustrated by the fact he was promoted to full professor in 1996, a decision he says was approved by the then-Minister of Education himself.

Not done yet

These days, Chua stays mostly out the public eye, diligently working on his academic and teaching work.

When I ask him why the public hasn't heard from him much recently, he tells me:

"I don’t want to make comments if I don’t have anything radically different to say. I think that later on I will start to be more vocal about poverty issues."

That last sentence brings a bit of a sparkle to Chua's eyes, as he sinks deeper into his desk chair.

It's clearly an issue that he's passionate about, one compelling enough to bring his voice back into the public sphere.

"Inequality is not something you can solve but poverty is something you can solve. Society may be stratified, but there’s no reason why the lowest rung needs to be poor.

I think we can make poverty history; we are the one nation that can do it."

Watch this space.

Image from Lauren Choo

Image from Lauren Choo

Top image by Lauren Choo

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.