Darren Mak is quite the rarity.

Aside from being a polyglot who understands a whopping 14 languages, the 25-year-old is also a Chinese Muslim.

Meeting him for the first time, it's hard to believe that this unassuming young man used to be an angry, suicidal teen who was openly hostile towards organised religion.

"Religion to me was like, no," says the self-professed "ex-hardcore atheist".

But perhaps that's what makes Mak's story all the more remarkable.

"I thought about death a lot"

Growing up, Mak's teenage years were particularly troubling.

Aside from doing poorly in secondary school, he was also a heavy drinker prone to bouts of self-harm. There were days when he would down bottles of vodka, which he would buy himself from convenience stores, and go to town on his thigh with a penknife.

"In the moment, you just want to hurt yourself," he says.

Only much later, at the age of 17, was Mak able to put a name to what he was going through when he was diagnosed with it: Depression.

But before that, his anger and ennui drove him to contemplate death.

"I thought about death a lot honestly, because I was thinking what is the point? I would sometimes research what is the most painless way to go and plan how to kill myself."

It led to two suicide attempts, one of which landed him in the hospital.

"One day, my mum was waking me up to go to school and then I just threw up because I swallowed like 30 Panadol pills the previous night."

Mak was lucky. At the hospital, he was told that any further delay in his admission would have resulted in irreversible liver damage.

His suicide attempts and self-harm affected his family, especially his mother.

This, sadly, didn't make him feel worse about what he did. Instead, Mak used this to add justification to his quest for death, so his family wouldn't be hurt anymore.

"It's very warped thinking, but when you're trapped in that, there's nothing else you can think about," he says.

It was against this backdrop that Mak had a dream one night that came so out of the blue, he says it changed his life.

Dream of the Kaaba

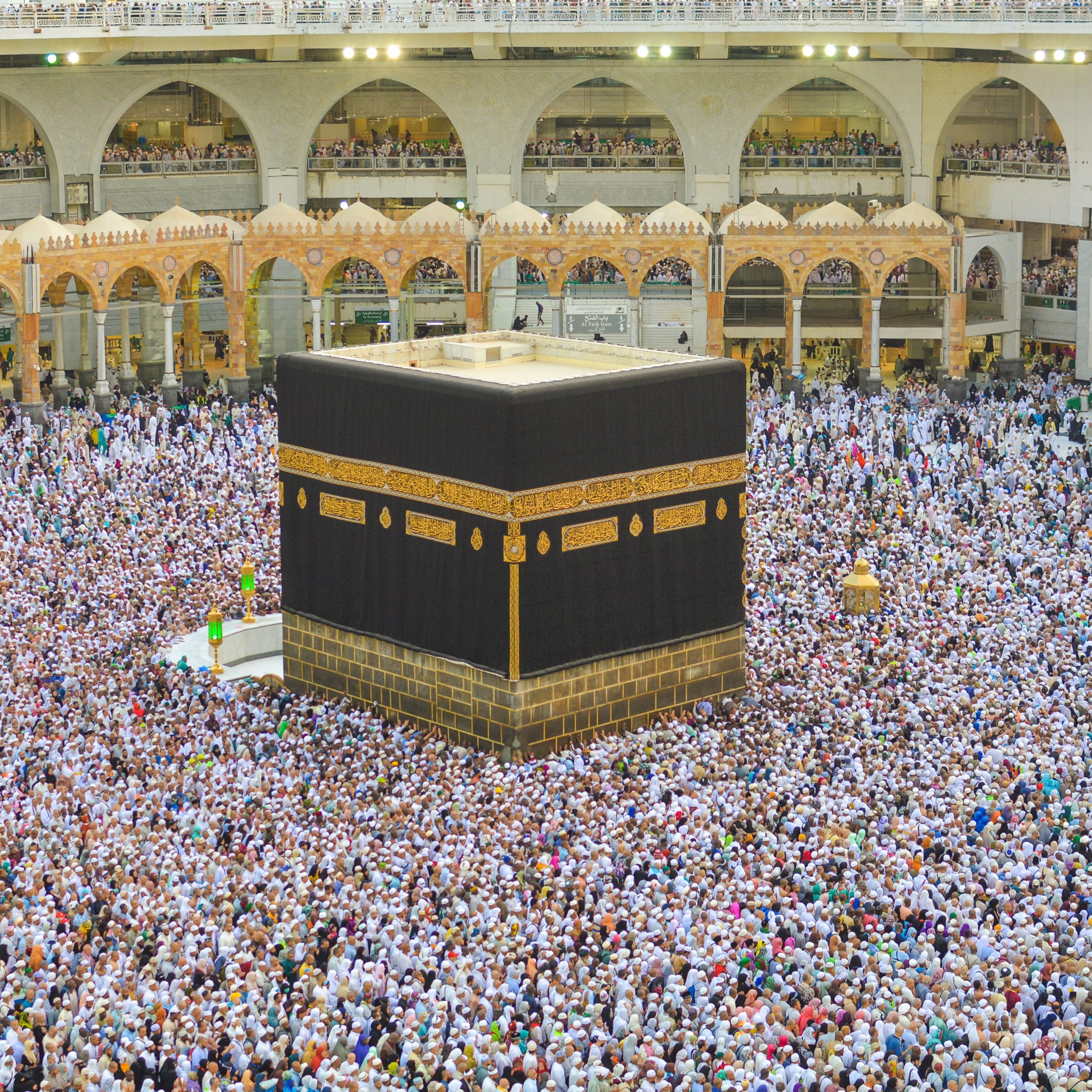

Around the time he was diagnosed with depression, Mak dreamed about — of all things — Islam's most holy site.

In his dream, he saw the Kaaba, and distinctively felt the instruction to:

"Lay down your burdens and face Mecca."

The Kaaba in Mecca, Islam's most holy site. Photo by Adli Wahid on Unsplash

The Kaaba in Mecca, Islam's most holy site. Photo by Adli Wahid on Unsplash

Having had no prior knowledge of Islam or the Kaaba, Mak was bewildered that he would dream of something so specific. But as someone who believes in fate, he took this as a sign.

"I was really spooked," he says with a slight chuckle.

He slowly explored Islam and did his own research for about two years before deciding to take the plunge and sign up for a conversion course when he was 19.

Being a polyglot did come in handy.

"Some of the languages (I know) are a little helpful when studying Islam, but my main materials are still in English," he says.

When Mak announced his conversion on Facebook, people thought he was pranking them.

"Somebody actually texted me, 'this is a joke right?'"

Others could tell that Mak was a changed man, though.

Once, following his conversion, Mak was catching up with a secondary school friend over dinner.

Five minutes into their meal, he recalls his friend suddenly saying to him, "Hey Darren, I just realised you haven't said a single swear word yet."

It was an amusing revelation for Mak, who admits he used to swear a lot ("I was a very angry person").

Mak's mother was quite happy with the change in her son.

"You have a sense of meaning; you are a better person, happier," she said to him.

His father though, was a bit more cautious since Mak's conversion happened during the height of the ISIS scare.

"He was so scared that I was turning into a terrorist. He was legit scared. To this day, that seed of doubt still manifests. Like when I say I'm going to Indonesia, for example, he will be like, 'doing what?'"

Darren Mak says he has become a better, happier person after converting to Islam. Photo by Rachel Ng.

Darren Mak says he has become a better, happier person after converting to Islam. Photo by Rachel Ng.

To eat or not to eat?

A large part of adjusting to his new life as a Muslim had to do with food, of course.

Adjusting to a new convert's dietary restrictions is a common area of concern for members of one's family who do not share the same faith. Should they stop cooking pork? Must all the kitchen utensils be replaced? Can the whole family still eat together?

"How do I cook for you now?" Mak's mother asked him.

"I was like, you can still cook what you usually cook. I just won't eat the pork lah," Mak said quite matter-of-factly.

"It doesn't make sense that my family stops eating pork because of me. I don't expect them to change their eating habits because of me."

Mealtimes can be, as Mak puts it, one of the areas that can cause friction between Islamic and non-Islamic family members.

Mak shares a piece of advice he received from a fellow convert who recently became a mother:

"She was like please ah, don't ask your mum to buy new kitchen, buy new stove, buy new everything just so that you can eat stuff that is untainted by pork. Don't need to make your mum's life difficult."

A little give-and-take from both sides when it comes to matters like this can help to prevent strains in relationships with family and friends, he says.

"At home, my kitchen got no halal certification but it's fine!"

This notwithstanding, however, Mak says he was particularly touched by how an aunt went out of her way to accommodate his new dietary requirements.

"She would specifically prepare a different thing for me. I didn't even have to ask her, but she did it willingly."

Similarly, his grandmother now always makes sure there are at least two dishes on the dinner table Mak can eat at family meals, and point out to him the ones that are not suitable.

When it comes to Muslim festivities, Mak doesn't celebrate them on the day itself, because he would be alone:

"I do celebrate Hari Raya Puasa and Haji, but typically not on the day itself as most people are busy with their own families. I might just spend it myself or with the few friends here and there who happen to not be spending it with family."

Opening his eyes to struggles of the Muslim community

Being a Chinese Muslim also gives Mak a unique perspective about the struggles of the Muslim community — like finding places to eat in Singapore, for example.

"Halal food is not cheap. It is at least S$2 to S$3 more expensive on average per meal and it adds up! And when I realised that I can only eat from that one store in my school for the next four years of my life, I was like... (sighs)"

Mak at Baalwie Mosque. Courtesy of Darren Mak.

Mak at Baalwie Mosque. Courtesy of Darren Mak.

And since Mak doesn't look Muslim/Malay, he is thankfully, spared from the micro-aggression that his fellow Muslims encounter, many on a day-to-day basis.

Once though, when a cab driver found out that Mak was Muslim, he warned him to be careful because "Islam always got things". He didn't elaborate, but it was clear to Mak where the conversation was heading.

"It opened my eyes to the difficulties that Muslims experience here," he says. "And these are things that non-Muslims don't have to think about."

A crisis of faith

Starting his journey in Islam, Mak devoured as many resources as he could find — from the Quran (the Holy Book) to Hadith (words of the prophet Muhammad) to even scholarly work from the 13th and 14th centuries.

He even read materials from Saudi Arabia, which tend to have stricter schools of thought.

And boy were they strict: you cannot take photos of people, cannot eat in restaurants with no halal certification, and cannot use your left hand — just a few of the more "extreme" interpretations of Islam that Mak himself tried to adopt as a new Muslim.

"These are very small things but it's the obsessive level of detail you give it," says Mak.

There are some who won't even shake hands with the opposite gender, and for a while, Mak genuinely believed that he must not either.

"But I felt so suffocated because most of my friends are ladies and we used to hug when we say goodbye and suddenly I felt like I can't be close to my friends anymore and that was honestly a big cause of upset for me."

You might think of polygamy, child marriage, and slavery as relics of the past, but there is a small group of Muslims in Singapore that still believes in them.

"It really bothered me. This is not right. You call it religion, but this doesn't sound right," Mak says, cringing.

As he read more widely, and sought the advice of other Muslims who were more learned than him, Mak came to realise that that form of Islam was not his cup of tea.

"But I believe in things being fated and I do believe that kind of journey has meaning," Mak says. And now, his understanding of Islam has evolved to become more pluralistic — accepting a more diverse range of interpretation.

Personal views of Islam do not sit well with some Muslims

Mak also acknowledges that this view does not sit well with some Muslims who see it as "shopping" for the best, or "most suitable" bits of the religion.

"Many of these anti-liberal stances, the underlying principle is that they refuse to acknowledge diversity. And so now I know that these are completely antithetical to my own personal principles."

Mak says his study of Islam and his own travels has helped to reinforce his observations — that like a lot of other faiths that exist in the world, Islam is practised differently by different people.

He found on a trip to Turkey, for example, that most Muslims there are absolutely fine with keeping and touching dogs, unlike here in Southeast Asia.

Mak at a Muslim intra-faith event. Courtesy of Darren Mak.

Mak at a Muslim intra-faith event. Courtesy of Darren Mak.

"The world is just so big. There is no way for everyone to be the same in terms of belief, action, and practices," he says. But he qualifies that differences in opinion have to ultimately come from the same foundation and value system.

Take LGBT issues for example, which Mak says is an issue that requires a very nuanced response.

"You need to be very respectful of advances in the field. Gender studies have only developed recently. You can't be going back to things from 600 years ago when the concept of gender was very different back then."

Plus the fact that slavery, child marriages, and polygamy are largely considered taboo in most modern societies today has convinced Mak that while the fundamentals of religion remain the same, the practical application of them changes over time.

"I don't believe that the essence of the religion has changed. It's still about compassion, still about mercy, still about finding justice, and development. But the form that it takes can be very different."

Differences in thinking in Islam have always existed too, he points out.

For example, some schools argue for the physical manifestation of God, while others insist that it is conceptual, says Mak.

"Religion doesn't necessarily entail blind following," says Mak. "This was a very recent realisation for me."

As we conclude our conversation, I ask Mak if he would have converted to Islam if he wasn't depressed.

"I don't think I would have, honestly," he says after giving my question pause.

"If I had been in a very comfortable position previously, there would have been no need for me to change anything."

Mak's story is one of many you can find around about the saving grace of religion.

But more importantly, I am amazed by how it has provided him with the unique ability to bridge the gap between two very distinct groups of people through his message of acceptance.

I'm pretty sure this won't be the last we hear of him.

Top image by Rachel Ng.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.