Singapore consistently ranks highly on Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which assesses the ability of 15-year-old students from the participating countries to apply knowledge and skills in three areas: Reading, Mathematics and Science.

However, 2018 PISA results announced this year also revealed that 15-year-old students in Singapore expressed a greater fear of failure compared to their peers overseas.

Referencing this finding, Joanne Lim contributed an opinion piece exploring suggestions on how to conquer this by rethinking how we define failure, success, as well as education.

Lim is the Founder and Creative Director of The Right Perspective – a consultancy specializing in writing, strategic communications, branding initiatives, and creative services for businesses, institutions, and individuals.

We have published her opinion piece here.

By Joanne Lim

The latest PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) survey by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) revealed that Singapore students are more afraid of failure than their 15-year-old international counterparts.

Young students in Singapore indicated that they are concerned about how others thought of them when they “failed”; failure also made them doubt they had enough talent, and called their plans for the future into question.

This fear of failure is of grave concern if Singaporeans believe that our country’s future success lies in a strong spirit of innovation, creativity, and enterprise. We need to understand this as a deep challenge for Singapore’s society, and not simplistically as a problem with the education system.

As love is the opposite of fear, I believe that the only way we can conquer the fear of failure is with love.

To conquer the fear of failing, we need to inculcate within ourselves and our young a love of learning (instead of a fear of results), a love of doing good for others (instead of a fear of losing out to others), and a love for humanity (instead of a focus on grades).

We also have to rethink how we define failure, success, as well as education.

The ultimate mistake is to not do anything

Young children learn so much and so fast. For them, “failure” does not exist. They discover “failure” only when parents, friends, and relatives use the words “fail”, “stupid,” and “lazy”.

The late Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s first Deputy Prime Minister, was a master at thinking out of the box.

Source: Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA).

Source: Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA).

When he was Minister of Defence and had to quickly build up a credible Singapore Armed Forces, he steeled his people to do what had never been done before by declaring: “The only way to avoid making mistakes is to not do anything. And that will be the ultimate mistake.”

Failure lies in not thinking and not trying.

Failures are often unavoidable despite our best efforts, because we simply cannot know everything when we work on something new, and mistakes are the way to discover what we do not know.

We need to love trying and value effort over results

“Learning by doing”, a theory of education that involves learning through building up knowledge and experience on the go, rather than separating practice from theory, is the only way to learn quickly and to understand deeply.

As Confucius is reputed to have said: “If I hear, I forget; if I see, I remember; if I do, I understand.”

And success upon the first attempt is extremely rare. In fact, we often learn more from failures than from successes.

Thomas Edison, often described as America's greatest inventor, was very well acquainted with “failure”. In his quest to invent a ground-breaking storage battery, Edison conducted more than 9,000 experiments without any breakthroughs.

When his close friend, Walter Mallory, pointed to his lack of results, Edison profoundly responded: “Results! Why, man, I have gotten lots of results! I know several thousand things that won’t work!”

We fail only when we do not try and when we do not do our best.

To conquer the fear of failing, we need to love learning and love trying.

Parents need to love their children for trying their best, teachers need to value their students on effort, and society needs to value best efforts over achievement.

Success in life is about being better human beings, and not better robots

While it is important to redefine and rethink failure, it is equally important to redefine and rethink success. As we are not robots, we should see success in terms of humanity and not productivity.

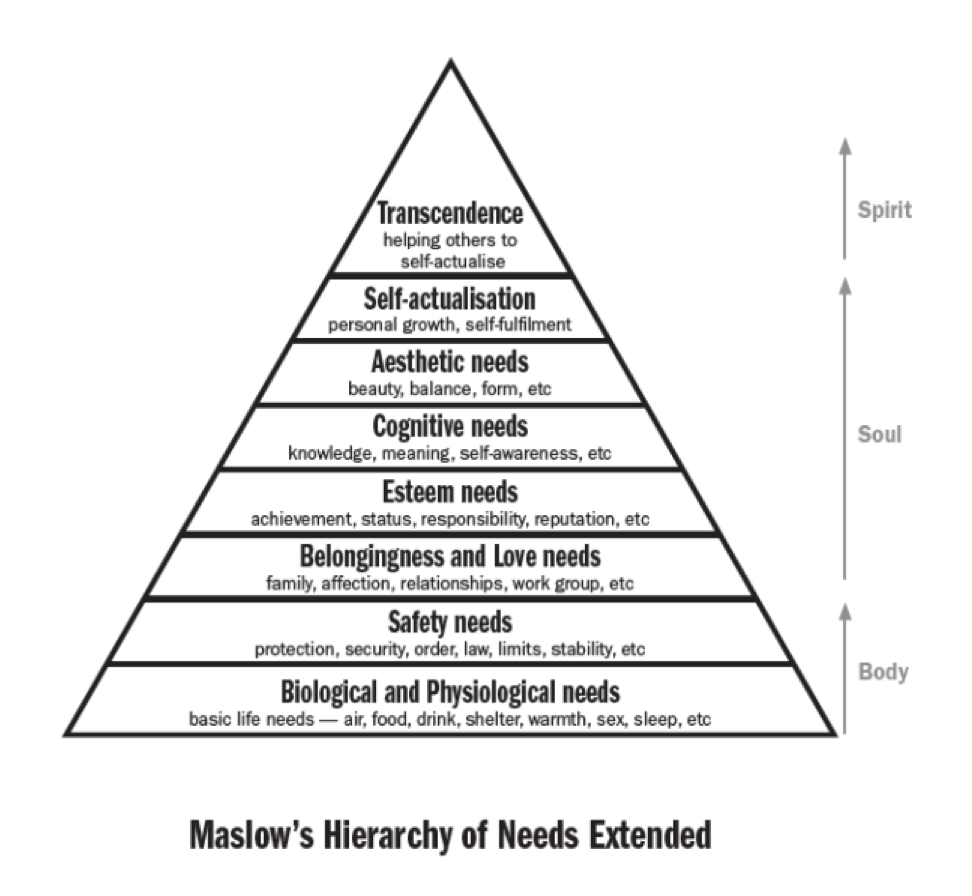

Further research into “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” has concluded that our highest need as human beings is “transcendence”.

Photo via Winning with Honour (World Scientific, 2016)

Photo via Winning with Honour (World Scientific, 2016)

Desiring the best for others and doing good beyond ourselves is in fact a higher need than “self-actualisation”, which is being the best we can be according to our talents and abilities. We best succeed as human beings when we help others be the best they can be.

In another study, Harvard University spent 75 years researching what human beings need to flourish in life. The most profound finding was: “Happiness is love. Full stop”.

The study showed that relationships with other people, not one’s grades in school or one’s wealth, mattered more than anything else.

The late Steve Jobs expressed this beautifully in this quote:

“Being the richest man in the cemetery doesn’t matter to me. Going to bed at night saying we’ve done something wonderful . . . that’s what matters to me.”

To conquer the fear of failing, we need to be clear what it means to succeed as a human being – that is to love and make life better for others, and not only for ourselves.

That which cannot be digitised will become increasingly valuable

Futurist Gerd Leonhard noted that in most of the futuristic industries, technology can take two paths that he calls “Hellven” – the technology can be “heaven” (where it is used to raise the well-being of people) or “hell” (where it brings about bad consequences).

While technology has progressed exponentially, humanity has only progressed linearly; while technology does not have ethics, people depend on it.

In addition, Leonhard believes that anything that cannot be digitised will become more valuable, and that in a world of automation and abundance, experience will become extremely valuable.

In an “experience economy”, people will be more willing to pay for bespoke services and will value more highly the human traits that include intuition, love, trust, and understanding.

Creativity, innovation, social intelligence, and customer focus will thus be very important for every business. Employees need to be skilled in creative problem-solving and constructive interaction if they still want good jobs.

What this means is that organisations and their staff must not only excel at skills and technology, but also at humanity.

Education should thus be focused on developing our children’s capacity as human beings and their skills, and not on perfecting their grades.

Young people in Japanese society have a warped view of work

In his book, A Compass to Fulfilment, Kyocera Corporation founder Kazuo Inamori opined that “education must foster a proper understanding of the meaning of work”.

He observed that in Japanese society, a person’s educational background determines his or her worth, and that children who excel at their studies are given preferential treatment and are separated from those who do not.

This leads to young people having a warped view of work — good grades and a job with a well-regarded organisation are idealised, while “non-academic skills such as dexterity and the ability to get along with others are neglected”.

He suggested that children need to be taught there is a “tremendous diversity of occupations and that it is the dedicated efforts of each individual in [one’s] particular job that make daily life and progress possible”.

We should be valuing contribution to humanity

Education should therefore be a means to empower children with not only the practical knowledge and skills, but more importantly, the wisdom that they need for their occupations.

It should also not matter what their occupations are, as long as they contribute to the common good of society.

This means that we need to be a society that honours the cleaner who does his best to keep the toilets in good condition as much as we honour the founder of a unicorn start-up.

To conquer the fear of failing, we need to value one’s contribution to humanity over grades.

We need to appreciate and honour everyone who is doing his or her best to contribute to society according to their varied talents and abilities, no matter how much money they might earn or how visible or invisible they might be in society.

And if we think that this is too difficult to achieve and thus we should not even try, let us recall the late Dr Goh’s words: “The only way to avoid making mistakes is to not do anything. And that will be the ultimate mistake.”

Top photo via Unsplash.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.