“We Built This City” is a new series of feature interviews on Mothership, tracking the contributions and efforts of the pioneers of modern Singapore. In these, we sit down with people who had key roles to play in the foundations of our fledgling nation, and tell their stories of the very grown-up decisions they had to make for the country at very young ages, some known, and some kept hidden till now.

This week, we talk to Liu Thai-Ker, the man who literally built this city in various roles that he held at the Housing Development Board and the Urban Redevelopment Authority. This interview was done in two parts, of which this is the second.

You can read the first part of our interview with him here.

You would think after 14 years spent overseas honing his craft, a 23-year civil service career, and 27 award-winning years in the private sector that Liu Thai-Ker, Singapore's former master planner, would have acquired a vast wealth of knowledge.

Not so, apparently.

"I don’t want to pretend to know everything. I know only two things: architecture and planning," the 81-year-old says good-naturedly.

Still, over the course of the few hours that Liu spared us for our conversation, it was pretty clear to us that he was selling himself a little short.

After all, you can't spearhead the modernisation of a nation without picking up some wisdom along the way, and fortunately, Liu was more than willing to share some of his opinions and anecdotes on a variety of topics that ranged from working with the late Lee Kuan Yew to revisiting his controversial position that Singapore needed to plan its infrastructure for a population size of as large as 10 million.

The requirements of the heart, brain, and eye

As Singapore's master planner and chief architect, Liu was tasked with building a city that was functional, providing its citizens with world-class living standards.

At the same time, as the son of the late renowned painter Liu Kang, the junior Liu had artistic instincts to sate.

In fact, he has been known to describe the role of architect and planner as requiring "a heart of a humanist, a brain of a scientist, and the eye of an artist".

"When you plan a city, the most important thing is that the city must function well. If you compare with a human being the most important thing is not the dress that she wears or the makeup she puts on. No, it's how well the organs are put together to make her function well and therefore healthy."

Hence the need for "a brain of a scientist".

But it can't just be utility without attention to form; plonking a functioning city on the ground would never do for a man of Liu's artistic pedigree.

"You have to romance the land, with an artist's eye. You don't just bulldoze the land flat. That's why in Singapore, despite the smallness, you still see hills, rivers, creeks, jungles in their original form."

He points to the example of Xiao Guilin, a quarry that the government originally wanted to fill in to use for public housing.

"I said 'No way. This is too beautiful to be wasted!'"

Xiao Guilin. Image by Jnzl via Flickr

Xiao Guilin. Image by Jnzl via Flickr

Lastly, for Liu, before a spade breaches the earth, a planner must have a "heart of the humanist".

"The ultimate goal for a planner is for people and for land. Only two words. If you care for the people, if you care for the land, you are a good planner.

People: to help them have a liveable life, and to make society resilient.

Land: to be functional and also sustainable. That means you don't destroy the ecology."

The best buildings "show respect to their neighbours"

So what makes an aesthetically-pleasing city then?

"Personally, I feel that the beauty of a city depends not so much on variety, but in it's own harmony. The modern aesthetic sense to me is very unhealthy.

For example, why do you think Paris is so beautiful? The old one, not the new one. It's because most of the buildings are boringly similar. Same height, same coloured stone, same kind of roof. And then occasionally because everything is boringly the same you have a few Eiffel Towers that stand out."

Liu thus decries the modern desire for every building to stand out — "what you get is a plate of chap chye".

While refusing to tell us what his favourite building is ("it's too controversial," he says), Liu tells us that he finds buildings that "show respect to their neighbours" to be the "better buildings".

"The buildings that want to show off themselves, they're not good buildings."

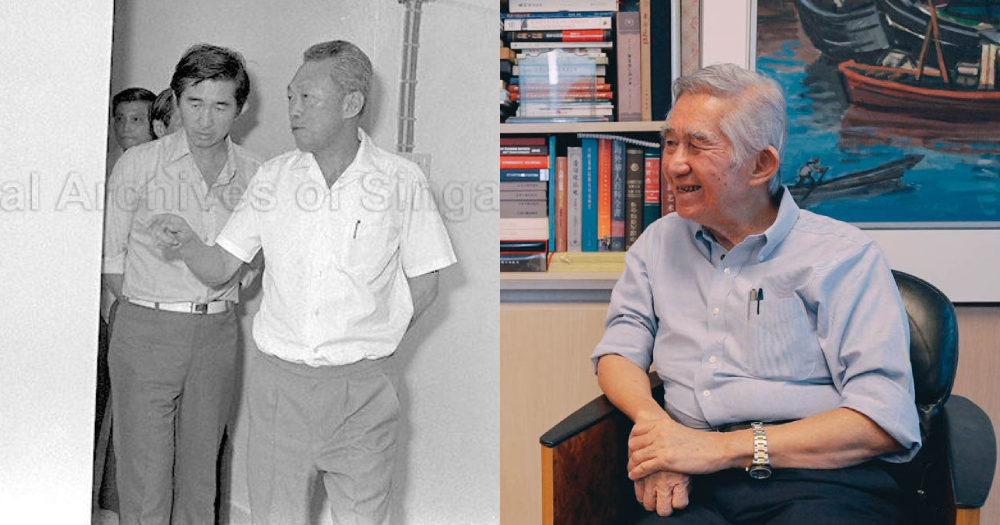

Working and having lunch with Lee Kuan Yew...

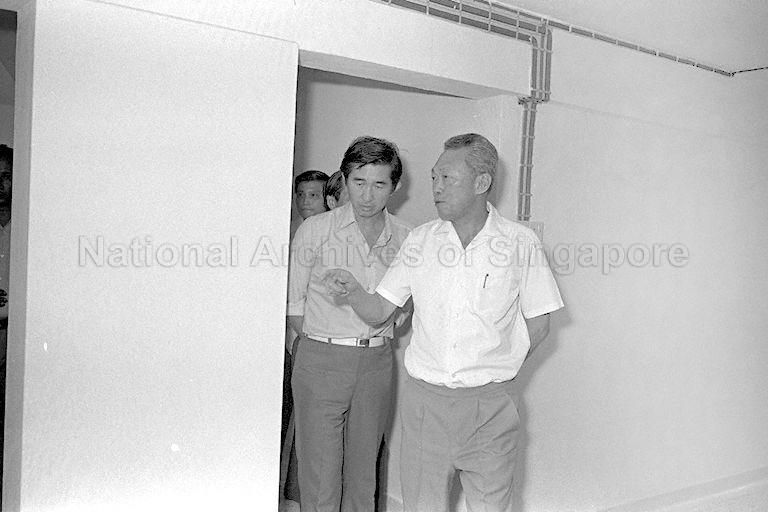

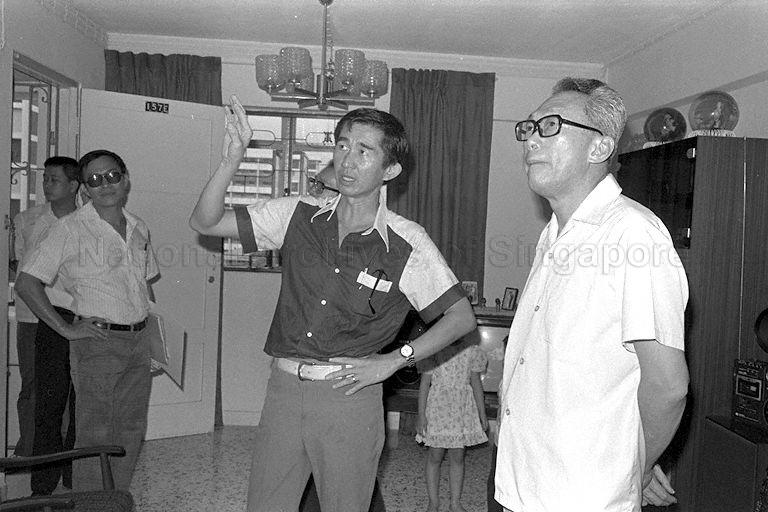

Photo by Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Photo by Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

It would have been impossible for Liu to spend a combined 24 years as head of HDB and URA without coming into contact with Singapore's founding father Lee Kuan Yew.

And what was the man like as a boss?

"He was an excellent leader, an excellent person because of his great concern for housing Singaporeans and his success in housing everyone."

As early as in 1975, when Liu assumed the role of Singapore's chief architect, he recalls Lee would request that he accompany him on walks around new housing estates.

These walks, which happened two or three times a year, would come with a barrage of "searching questions" from Singapore's then-prime minister.

To top it off, Lee often called for one-on-one lunches with Liu where the conversation would centre on the following:

- An update on what Liu was up to

- Liu responding to any questions Lee would have, and

- A discussion of Lee's new policy thinking

"Some MPs asked me, 'are you not scared of having lunch with him?' I said 'no, I look forward to it all the time!'

Because if you have a leader who’s highly rational, how can Singapore fail if you have a leader like this? Highly, highly rational.

In fact, I often tell people, our highest authority is not the prime minister nor the president. Our highest authority is rationality."

... and even disagreeing with him and changing his mind

Lee's commitment to rationality was good for Liu — the latter shares it helped empower him to disagree with Lee when it was necessary.

He even managed to change his mind on a few occasions.

"If he told me to do something that I disagreed with, I would just tell him straight to his face. And he would just immediately withdraw. But you must give him good reason. If you don’t know your stuff and just bullsh*t your way through he will just counter-attack you. I’ve seen him do that to other people, severely.

Around 1981, he gave HDB an instruction to clear up all the remaining squatters in three years. So I discussed with my colleagues, and we decided that if we cleared up in three years, we would have to bring our annual building programme sharply up. If you bring it sharply up, cost goes up. And after there will be unemployment.

So I wrote back to him and said 'for these reasons, it’s better to clear in five years instead of three years'. It was accepted just like that."

Liu and Lee visiting a resident's home during PM Lee's tour of Clementi HDB estate, circa 1979. Image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Liu and Lee visiting a resident's home during PM Lee's tour of Clementi HDB estate, circa 1979. Image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

According to Liu, part of what made Lee a leader who was great to work for was the autonomy he gave his subordinates.

"He will never tell me 'how', only the 'what'. He was so disciplined, he would just tell me what he wanted, and then leave it to you to figure out the 'how'."

Yet, with the autonomy came a heightened pressure to perform.

"It was good in the sense that I had the freedom to devise the best method. But bad because in the event that I did not deliver, I’d probably get the sack.

Thank goodness I did not get the sack. I certainly was very much aware of the fact, that if I could not deliver I would get the sack. Because this man was totally rational. He does not allow the clarity of his mind to be swayed by emotion."

On the outsourcing of government projects

Liu believes that the same level of robust back-and-forth between civil servants and their political office holder bosses might be missing today.

"Before the government introduced the outsourcing of contracts to the private sector, we had to deliver everything ourselves and therefore we had hands-on experience. And therefore when Lee Kuan Yew gave us instructions, given our experience we knew what could be done, what could not be done. So by disagreeing with him, it was really to help him formulate better policy.

But now, a lot of the government projects, including public housing, is outsourced. So the in-house technical professional competency is not as strong as before. And its a bit harder to advise the minister. I'm a little bit sad that the competency level has dropped because of outsourcing."

Clarifying that he is "not totally against outsourcing", Liu says that while having it allows the government access to a diversity of designs and approaches, keeping some things in-house would be beneficial.

"My wish is that they outsource half of the projects but keep half of it in-house competency."

That 10 million population recommendation

While he's largely been out of the spotlight in recent years, Liu occasionally pops up in discussions about his now-quite-infamous projection of Singapore's population eventually growing to 10 million.

Almost a decade ago, Liu had suggested that Singapore should work towards accommodating a population of 10 million, a stance he has reiterated multiple times over the past few years, most recently in a The New Paper interview two years ago.

Earlier this year, Heng Swee Keat was quoted by The Straits Times citing Liu's projection and encouraging Singapore to remain open to immigration.

When we asked Liu about this, we weren't so surprised to learn that he continues to stand by it.

"Let me explain the urgency of the matter. In 1960, we had 1.6 million people. In 2018, our population grew by 4.2 million to reach 5.8 million. What's 10 million? It's to add another 4.2 million.

So in 50 years, we grew 4.2 million, I add another 4.2 million, even if we grow at half the speed, that projection will only last 100 years. Is that excessive?"

For Liu, the issue of increasing our population is tied very much with the country's ability to sustain its economic growth — something that Liu believes needs to be maintained if the island nation is to maintain its sovereignty.

That's why he believes that plans for a population of 10 million must be made now so that Singapore can develop and allocate its land prudently accordingly.

"I did a rough calculation — if we decide that we are going to plan for 10 million, and assuming that we keep all the landed properties, all the green areas, all the bungalows and so on — we can accommodate 10 million but we have to increase the density of our new developments by 30 per cent.

But the longer we wait, the longer we don't face this problem, the higher the density will have to be in the future. The longer we don't face this, the less land that will be available."

The greatest danger to Singapore

In Liu's mind, while Singapore today is established and recognised as a developed nation, maintaining the sovereignty of our nation-state remains as crucial a task for this generation as it was for his.

But while generations past had to weather hardship, Liu reckons that it is ironically the comforts of modern Singapore that they worked so hard for that pose the biggest threats to our future.

"Historically there are many cities that used to be at the peak of the world, but yet now they are nothing. Complacency does not help Singapore to stay ahead.

When you were poor, of course, you fear for survival — you have to work. You have to aim for excellence. When you were not poor, you still have to fear for survival, still have to aim for excellence."

He cites the difference in national rhetoric between today and the early days of Singapore's nationhood.

"Certainly throughout the entire '70s, if you look at newspapers, the word 'survival' appeared in many ministers' speeches. Now we don't talk about it, but in my view, we still have to worry about our survival.

You see our problem is that we are a small country; we have totally no resources. The only resource we have — these are Mr Lee Kuan Yew's words, not mine — are our humans. So if we do not shape ourselves very highly, then I think we're going to be in trouble. Our survival and our staying among the higher ranking countries of the world was because in those days, the words on everyone's lips were 'in search of excellence'."

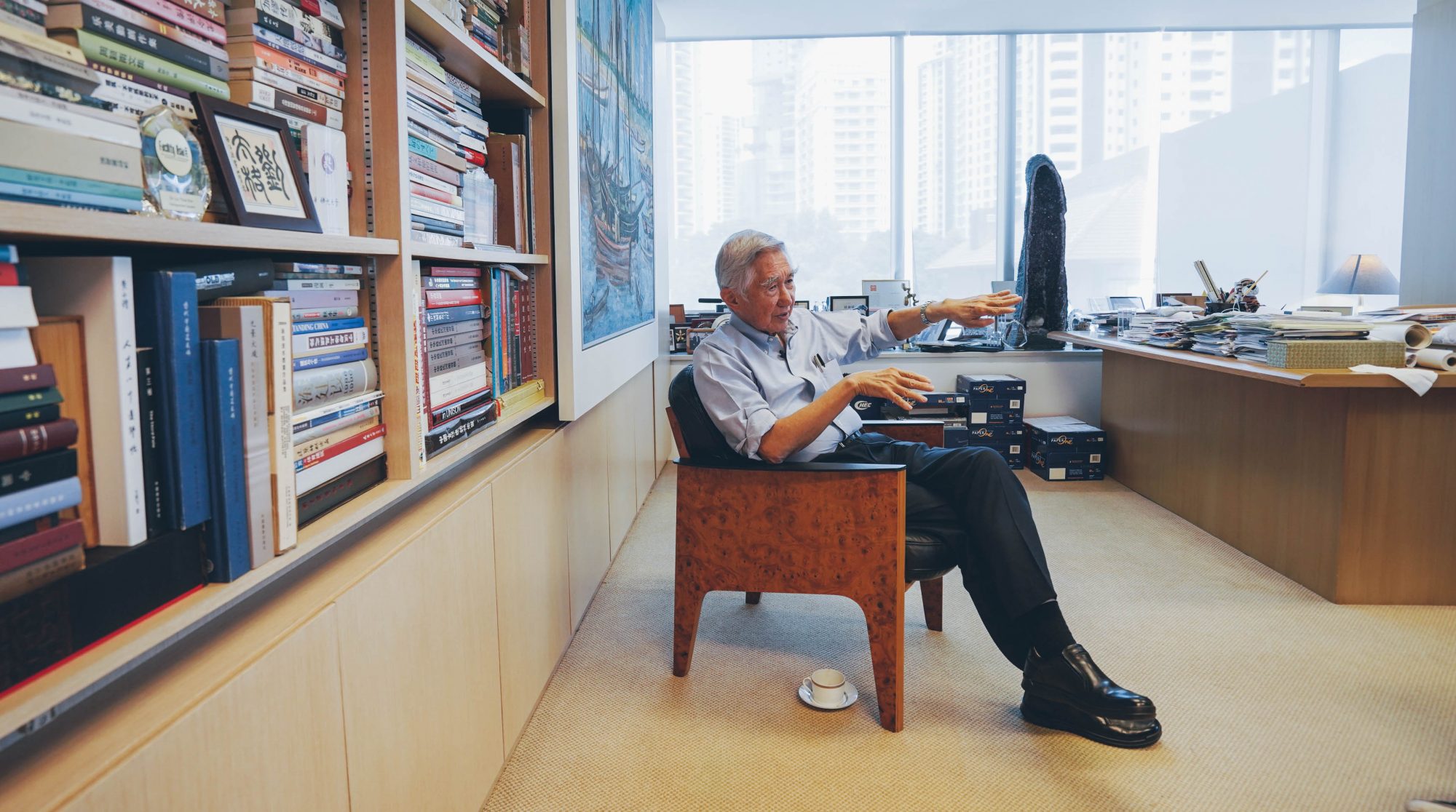

Photo by Jane Stephanie

Photo by Jane Stephanie

And lastly, why immigrants are important to Singapore

However, Liu feels Singapore faces yet another challenge in our efforts to excel.

"We are unique in the sense that we are a one-city country," he explains.

And while coupled with a single-tiered government that brings about great efficiency, Liu believes that it comes at the cost of innovation and creativity.

"In bigger countries where you have different cities, the people who live in different cities are somewhat different from each other. So when they meet, they don’t automatically agree with each other. Therefore they argue and good ideas emerge. But here we are a single-city country. Everybody is educated under the same ministry of education. So, of course, the tendency for people to think alike is extremely high.

Therefore I think we should really appreciate having foreigners here to bring in different perspectives and different ideas, and help us find the best solution for the jobs that we're doing."

"I feel that Singaporeans should look at the positive side of having immigrants," he says, a wry smile beginning to form on his face.

In this global political zeitgeist, it's the kind of statement that opens the former chief architect up for another wave of criticism, though he can hardly be blamed for holding this point of view.

After all, Liu himself is a testament to the great impact foreigners can have in Singapore.

"I say it for a personal reason because I am an immigrant. I was born in Malaysia (laughs)!"

Read the first of our two-parter interview with Liu here:

Top image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore and Jane Stephanie

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.