“We Built This City” is a new series of feature interviews on Mothership, tracking the contributions and efforts of the pioneers of modern Singapore. In these, we sit down with people who had key roles to play in the foundations of our fledgling nation, and tell their stories of the very grown-up decisions they had to make for the country at very young ages, some known, and some kept hidden till now.

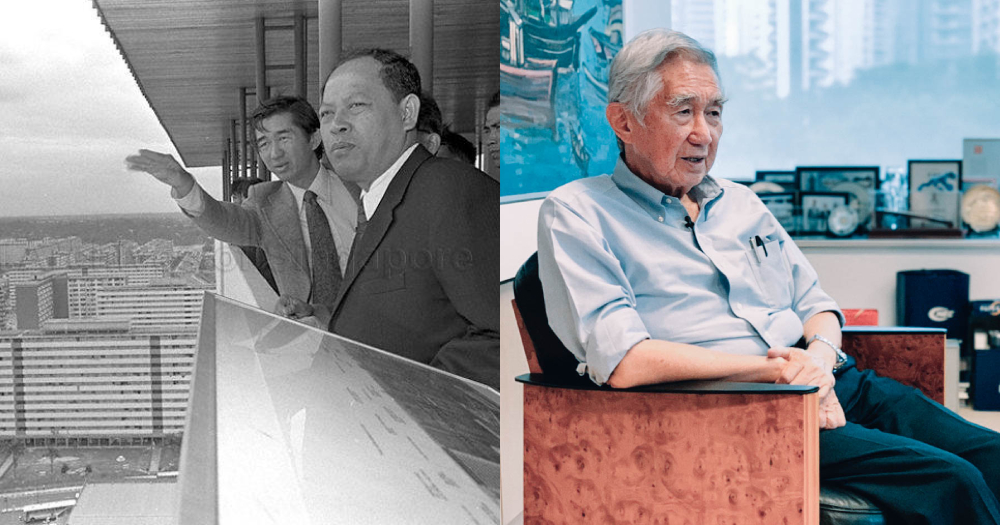

This week, we talk to Liu Thai-Ker, who was the chief executive officer at both the Housing Development Board and the Urban Redevelopment Authority. This interview was done in two parts, of which this is the first.

As Liu Thai-Ker reels off descriptions of old Singapore in vivid detail, his audience shudders.

This one anecdote from a rainy day in an undeveloped Redhill area is filled with an account of human faecal matter flowing down the streets and huts with plastic sheets for roofs.

“Water was dripping into the interior. That was the condition that people used to live in, in those days.”

Sitting down with Mothership in his office on Scotts Road, it's hard to imagine a time when Singapore was like that.

Not when nearby Orchard Road is lined with air-conditioned shopping malls and fancy hotels — all forming a steel and glass guard of honour for the flow of modern cars that pass through the area on a daily basis.

It’s an immovable testament to the lifework of the man known as the architect of modern Singapore.

Having spent 20 years working at the Housing Development Board (HDB) and then another four years at the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Liu oversaw and directed Singapore’s transformation from a third world collection of slums and squatters to world-class city.

And if you think this claim is crazy, you're right. But he really, truly, did. And we'll explain the story of how he did it as best as we can.

Growing up sleeping on cracked floorboards, cycling 6 miles to school

Liu himself grew up in what he describes as “abject poverty”.

He was born in Muar (a town in Johor) in 1938 before his father, the late prominent pioneer Singapore painter Liu Kang, moved the family to Singapore after the Japanese invasion ended

Liu recalls the family home — a rented terrace house in Dhoby Ghaut that once stood where School of the Arts is today — as being “better than most other people's, even though we were very poor”.

“Nowadays, I can sleep everywhere with no problem. Looking back I know why,” he muses.

With his parents unable to afford mattresses, his ‘bed’ consisted of timber wood floors — cracks and all — held together by wobbly galvanised iron strips and nails.

“If you can sleep in that kind of condition — can you imagine? Anything else is luxury to me.”

And as a student at Chung Cheng Junior High School, Liu would walk what he described as a one-mile (equivalent to 1.6k journey each way from Dhoby Ghaut. Later, when he was upgraded to the school’s Senior High campus at Goodman Road he had to cycle six miles (about 9.6km) each way.

It took about nine months for his father to save up to purchase a bicycle that would make his journey less arduous.

“Hardship yes, but in looking back, it laid a good foundation for my health today,” he says with a laugh.

A grand plan to ship himself to China to learn art

Despite performing well academically, a 17-year-old Liu graduated from secondary school knowing that his parents could not afford to send him to university.

He soon started work as a substitute teacher at Kong Hwa School, but always kept one eye on a different career.

“I was very sure that when I grew up I would be an artist.”

Not surprising, though, considering who his dad was — prominent calligrapher Chen Jen Hao also happened to be his uncle on his mother’s side.

After working for a few months, Liu saved up enough money to fund an ambitious plan.

At the family home, he announced to his parents that in two weeks time he would be on his way to China, having purchased himself a ticket on a freighter and had a plan to try his luck in enrolling in an art school over there.

Photo by Jane Stephanie

Photo by Jane Stephanie

A motherly intervention that compelled him to change his shipping destination

Perhaps knowing he could not offer his determined son a better alternative, Liu Kang seemed to accept his decision. His wife, however, was having none of it.

“No way! No way! If you go there I know that I’ll never see you again,” Liu recalls his mother howling.

Besides, he says, she had other aspirations for him.

“My mother — see this is the greatness of maternal love — not knowing a word of English herself, within two days found out that there was a part-time school of architecture in the University of New South Wales. She asked me if I would like to go.”

“Look, architecture is still related to art,” he remembers her reasoning. “But I hope you can earn more money and pull our family out of this abject poverty.”

“I was so moved… I said sure. Of course in my heart I felt that I certainly had to do something to comfort and please my mother. But after architecture I (had already decided I) will still become a painter.”

And so a mother with her weapons of mass persuasion — one part nagging, one part loving — convinced Liu to board a freighter, not to China, but to Australia instead.

Academic level: Asian

A S$10,000 donation from Lee Kong Chian’s Lee Foundation helped pay for Liu’s passage and education overseas where the plucky young man immediately set about building a reputation of overachieving.

“In those days Singapore was so backward, so I told myself, I must stand tall amongst the advanced country people.”

And by standing tall, Liu meant he had personally decided to "always be the top student". And somehow, just like that, he was.

As he had attended a Chinese school in Singapore, Liu had to first sit for a 'leaving certificate', which was essentially the last two years of the New South Wales high school curriculum combined into one year.

"I knew that my weak point was English — Math and Science I was very strong — so I spent a year mainly upgrading my English and I told myself that I wanted to speak and write as well as the Australians."

He ended up being one of three students from a cohort of 140 — of which Liu estimates half were Aussie — to receive a credit for his results in the English exam.

At the University of New South Wales, he attained first-class honours, of course, and at the same time picked up a university medal for being the tertiary institution’s best student in 11 years.

All the more impressive when you consider the fact that for four of his six years in New South Wales, Liu also studied art part-time at the East Sydney Technical College.

Yet, while he still harboured plans to be an artist after making money as an architect, Liu decided that it made more sense to focus his efforts.

“I felt that for me to contribute to Singapore, architecture was more useful. I was hoping that I could contribute to the landscape of Singapore. So I dropped art school.”

By the time he’d graduated in 1962, the transformation was complete — Liu had abandoned all his aspirations of being a painter and was now fully absorbed in being the best architect he could be. For him, this meant that he also needed to study urban planning, and to do this, he, you know, enrolled at Yale University in the United States. On a scholarship of course.

And naturally, two years later, Liu also received a medal while at Yale for being the faculty’s best student in three years.

But instrumentally, he formed close relationships with professors who would come to mentor him — one of these eventually introduced Liu to the late I.M. Pei, world-renowned architect-extraordinaire, who offered Liu a job at his firm in New York (because you know, it's that easy).

The experience of working under Pei’s tutelage proved invaluable, both from a technical and philosophical point of view.

Working at the legendary firm meant that Liu’s designs would constantly have to be reworked and refined until they reached the best standards.

Pei would also, on occasion, call Liu into his office for a private chat — “like a mentor,” says Liu. “I learnt a lot of his architectural thinking at that time.”

Patriotic yearnings

But after four and a half years, success at the very top of the private sector proved unfulfilling for the young architect whose sense of duty to his home longed to be sated.

From afar, Liu had watched as Singapore was expelled from the Malaysian Federation — the tiny island, that many at the time felt would not survive, left to fend for itself.

The contrast between Singapore’s precarious nationhood and the established unquestionable sovereignty of a country like the U.S. would not have been missed by Liu.

“My great desire was to change the fate of Singaporeans so that we could stand tall among the western countries. Because of that great desire, that’s why I told myself I must be the top student in every institution.”

As fate would have it, just as these patriotic yearnings began to boil over, HDB chief executive officer Teh Cheang Wan visited New York and asked to meet with Liu.

Over coffee, Teh offered him a chance to come back home, to contribute to the nation-building project.

“Looking back, he created that job for me, even though that position was not in HDB, to be the head of the Design and Research Unit.”

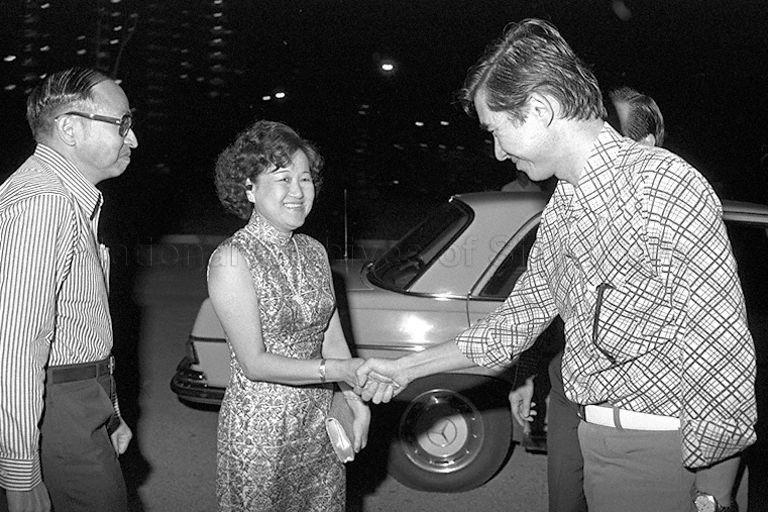

Liu (right) greets Teh and his wife at the opening a new HDB Clubhouse in Toa Payoh, circa 1980. Image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Liu (right) greets Teh and his wife at the opening a new HDB Clubhouse in Toa Payoh, circa 1980. Image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

That desire to contribute to Singapore is almost jarring, especially when many Singaporeans today dream of going in the opposite direction — moving overseas in search of a more glamorous lifestyle.

Liu said his sense of responsibility for Singapore stemmed from the tribulation he experienced and witnessed, something largely unheard of among the generation of today.

“If you haven’t seen the indignity of your existence the desire (to contribute to Singapore) might not be so strong. Under the British, I didn’t have citizenship. I was just a British subject, I didn’t have a country. Under the Japanese, I did not personally experience it, but I heard all the horrible things that they did.”

Part of the indignity he felt also originated from the living conditions he saw in Singapore's slums and squatters.

Inspiring pride in Singaporeans would require world-class homes, something Liu aspired to deliver throughout his 20-year stint at HDB, which also saw him rise to the position of CEO by 1979.

Engineering Singapore's way of living

Under his purview, the localised concepts of precinct, neighbourhoods, and new towns were developed and realised.

And with Liu planning 23 of the 26 new towns and estates that exist in Singapore today, it is no exaggeration to say that he literally designed and engineered the way of life many Singaporeans experience today.

Together with a team of experts from different fields — architecture, engineering, and sociology to name a few — Liu meticulously set about planning the little details of life most of us don't even think about.

One example is the optimal distance that Singaporeans have to walk from the outer reaches of a neighbourhood to the neighbourhood centre.

“A study showed that in a temperate climate, people would be happy to walk 600m. But in a tropical climate, people would only walk 400m. I couldn’t afford to have a neighbourhood centre with just a 400m radius because we wouldn’t have enough people there to support the neighbourhood centre. So I had to extend it to around 500m.”

There’s also the matter of creating a sense of community in these high-rise homes that replaced kampongs famed for their interconnected social networks.

The solution Liu and his team introduced was the concept of the precinct which was a sub-unit of a neighbourhood, and what they saw as the basic unit of a human community.

Each precinct was to have a good mix of family sizes who lived in one-to five-room flats, with a range of socioeconomic make-ups, capped at about 700 to 1,000 units per precinct.

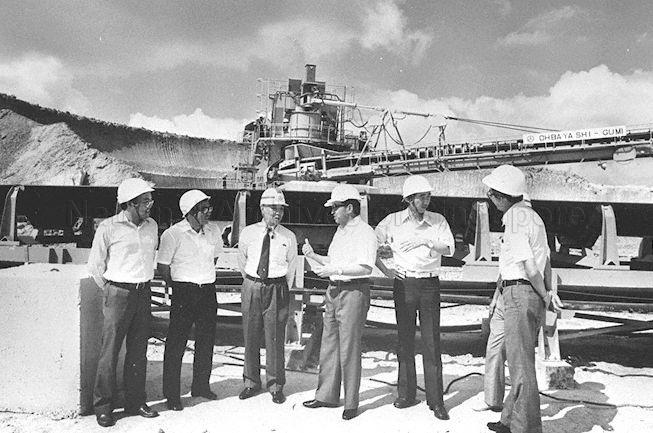

Teh (third from the right) and Liu (second from the right) touring reclaimed areas in Tampines and East Coast, circa 1980. Image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Teh (third from the right) and Liu (second from the right) touring reclaimed areas in Tampines and East Coast, circa 1980. Image from Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Even HDB corridors were designed with this purpose in mind, with Liu and his team eventually implementing a wider and shortened corridor that six to eight families could share as a community space.

“So when people now enjoy talking to neighbours and chatting with them, if they think ‘this ought to be like this lah’... well, no, it was created this way.”

Such is the attention he paid to detail at the time — and such is the power of his memory retention of all these details — that Liu was able to go deep into how he and his team designed precincts: defined as a cluster of six to eight blocks, often surrounded by bushes or trees, and including a playground (with sand pits for the younger children) and an exercise area.

"Also I'd been advised that the entrance to a precinct should be only one road," says Liu, still riffing.

In theory, this would mean that residents would be able to see anyone who came in and out of the area, creating alert should a suspicious figure with ill intentions arrive.

A world-class city

“That’s why I look very old,” jokes Liu. “I’m actually a much younger person. I look old because I put in a lot of hard work for Singaporeans.”

His favourite new town? It’s the newest one — or rather the latest one he personally planned, clarifies Liu with tongue firmly in cheek.

“Every new town, neighbourhood, and precinct is continuously improved. So the latest one is my favourite.

When people ask me which one is the best, I say the latest one — which is Bishan. And of course, a lot of people like Bishan because it has removed many of the flaws and incorporated many of the new ideas.”

By 1985, Liu and HDB’s hard work reached a climax with the last of the squatters and slums redeveloped into modern liveable spaces. It is at this point, Liu feels (even as he does say so himself), that Singapore truly became a world-class city.

Having decided that this achievement warranted an update to Singapore’s overall land concept plan — the long-term framework which guided the urban development of the nation — the government saw Liu as the perfect candidate for the job.

By 1989, he moved from HDB to URA where he assumed the role of CEO and chief planner.

The goal was no longer to make Singapore a world-class city — that had already been achieved. Instead, Liu was tasked with taking the young nation to the forefront of the developed world.

A plan that ensures we have "all the floor areas for all the activities for all citizens"

So in 1991, after what must have been an immensely tedious two-and-a-half-year translation of development projections from every government department into “drawings and space”, Singapore’s master planner unveiled his plan for how the nation’s 639.1 square-kilometre land area should be used in the coming decades.

“I often tell people that our concept plan of 1991 is a plan that ensures we have all the floor areas, for all the activities, for all citizens according to a world standard. Now how many concept plans can say that?”

For Liu, that meant achieving a goal of about 35 square metres of residential floor area per person in public housing, a world-standard that he instituted and protected in his concept plan.

“If you cannot give people landed property, we should at least give them world class floor area per person.”

By Liu’s estimations, the current floor area per person is somewhere around 27 to 28 square metres — a vast improvement on the 18 or 19 square meters per person that early Singapore offered.

Squatters in Seah Liang Seah Estate, along Serangoon Rd. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Squatters in Seah Liang Seah Estate, along Serangoon Rd. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

It’s also a figure likely to receive envious glances from a city often compared with Singapore — Hong Kong, which Liu notes only enjoys mostly 24 square meters per family (not per person, mind you).

Saying no, and then yes, to Xi Jinping

The following year, having achieved “not all, but most” of what he felt he had to do “to put Singapore on the map”, Liu decided that it was time to bring the curtain down on an illustrious public service career.

He had been invited to join RSP Architects Planners and Engineers as a director.

"Actually, my first love was not planning. It's architecture. So at that time, I thought 'oh good, an opportunity to say goodbye to planning forever!'"

However, Liu soon realised that the expertise and skills he had chalked up were rare and in-demand; his entry to the private sector saw Liu become a highly sought-after city planner.

The Marina Bay Cruise Centre. Photo via RSP Architects Engineers Planners

The Marina Bay Cruise Centre. Photo via RSP Architects Engineers Planners

Some of the buildings in Singapore he designed include the Marina Bay Cruise Centre and the Chinese Cultural Centre on Queen Street.

He has since had a hand in planning more than 50 cities around the world, even earning the respect of now-Chinese president Xi Jinping, who in his early-90s capacity as the party secretary of Fuzhou was so impressed by the Fuzhou city master plan Liu did as a public servant previously that he insisted that Liu also design the city's airport.

However, Liu had no experience in designing airports and initially declined Xi's proposition, prompting China's future leader to request a meeting with the city planner.

He wanted Liu to reconsider his decision.

"I explained to him why if I did it, I was being irresponsible — I had no previous experience (designing airports). Then he explained to me why he felt that I was the right person.

Because when he saw my planning for Fuzhou — first of all, I kept my timing very good, the quality was very good, the concept was clearly explained. So he felt confident — given my attitude to working professionally — he felt confident that he could trust me with creating Fuzhou airport."

The back and forth lasted somewhere between 10 to 15 minutes until finally, Liu realised that he could not change Xi's mind.

"Do I have a chance to say no to you?" he asked candidly.

"No chance," said a resolute Xi.

Fuzhou's airport, that Liu designed with help from Changi Airport's planning and design unit, went on to receive an award from China's Aviation Authority.

Fuzhou Airport. Image by SC Jiang

Fuzhou Airport. Image by SC Jiang

81 years old, and "I'll retire when I learn how to spell the word"

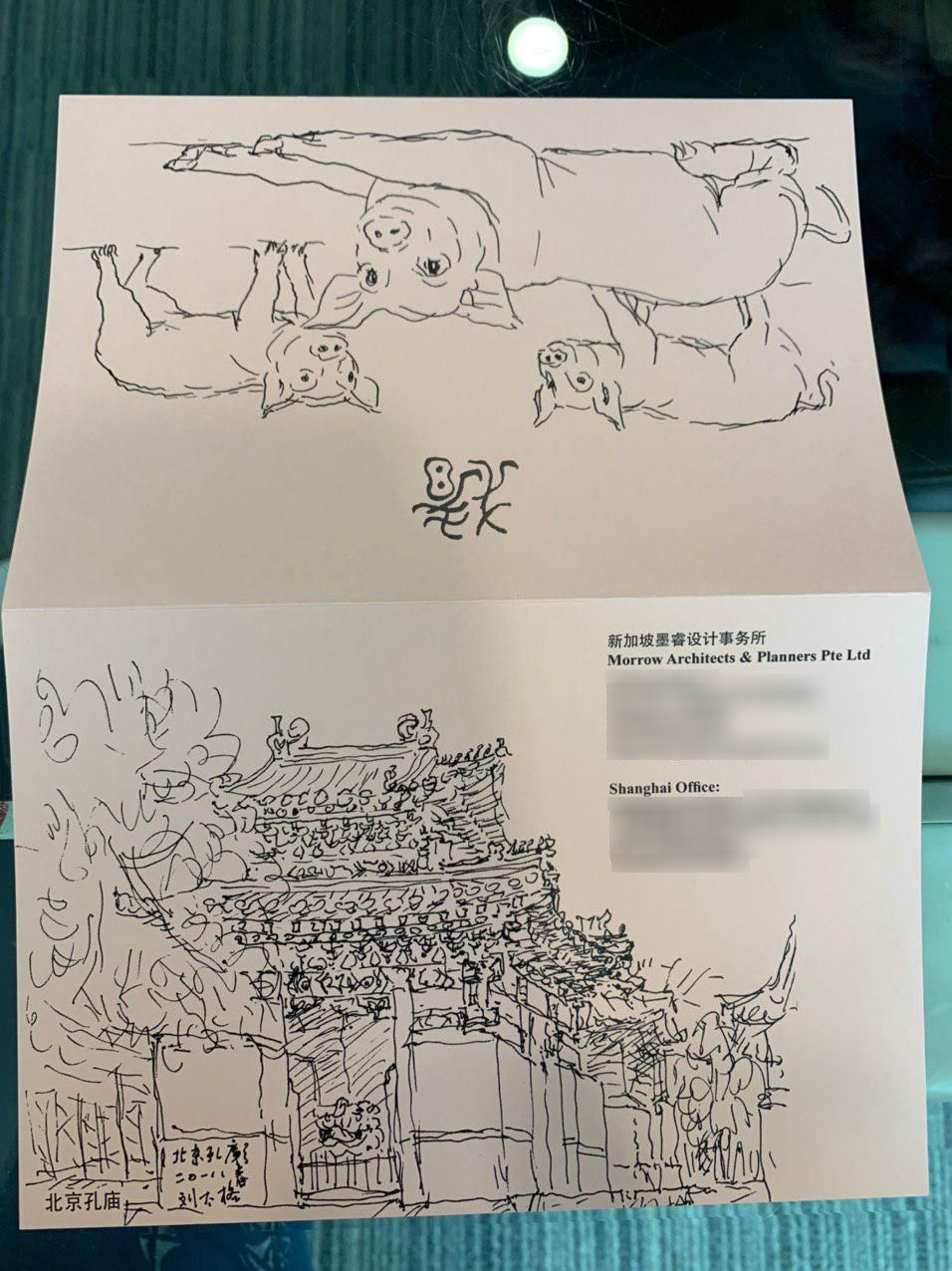

These days, Liu now heads up his own firm, named Morrow — a name taken from the studio his father used to run in the 1940s and 50s.

Now a ripe young 81, Liu is still at the office every day terrorising his employees (his words, not ours) when not travelling (which still happens very often) and, of course, continues to be very much involved in various projects around the world.

And while he never quite fulfilled his youthful ambition of being an artist, Liu makes sure to carve out time in his busy travel schedule to make sketches of scenery and architecture that catch his eye.

He then turns these sketches (done anywhere between 15 and 45 minutes either sitting or standing outside the structure or landscape, using a black gel ink pen tucked into his breast pocket) into festive season cards — often churches for Christmas, and Chinese temples for Chinese New Year — a tradition he has committed himself to annually without fail for the past 35 years.

In this year's CNY card, Liu drew pigs and the Beijing Confucius Temple on one side. (Photo by Jeanette Tan)

In this year's CNY card, Liu drew pigs and the Beijing Confucius Temple on one side. (Photo by Jeanette Tan)

The San Marco in Venice, one of his 45-minute sketches, on this Christmas card. (Photo by Jeanette Tan)

The San Marco in Venice, one of his 45-minute sketches, on this Christmas card. (Photo by Jeanette Tan)

While surely retirement must be on the horizon for the elder architect-planner, he's nought for admitting it — "I'll retire when I learn how to spell the word."

True to the spirit, when asked about what he would like to be remembered for, it seems that Liu has yet to think about life after work.

Taking a long pause to collect his thoughts, he finally replies with brevity:

"I would say that under my charge, I worked with my team of people to create a liveable environment and a sustainable environment for Singaporeans."

Over the few hours he has spent recollecting his life and expounding on his philosophies, this quote stands out to me as quite the understatement.

This might be only fitting, perhaps, because Liu's legacy is arguably best described not in words, but in every Singaporean's enjoyment (and the ability to take for granted) world-class living standards.

Top image by Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore and Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.