It was May 24, 1994.

After sending his girlfriend home having just had a dinner date together, 24-year-old Tan Kok Liang continued on his journey on his Honda Hurricane.

Things were going well for Tan.

The new NUS mechanical engineering graduate had just returned from a vacation in New Zealand and Australia, and was set to start work at American multinational company Proctor & Gamble in a week.

As his bike sped towards the expressway, Tan remembered the six gruelling interviews that he had to sit through just to get the coveted job.

He had beat out 7,000 applicants to get the spot.

It was tough but worth it.

He didn't see the police car stationed just round the bend of the expressway until the very last minute.

Speeding at 100km/h, Tan tried to veer his bike to the right but he heard a screech as his handlebar came into contact with the car door.

His front wheel jerked to the side, the bike careened over the car.

In the split second that Tan was suspended mid-air, he realised that his helmet was not properly secured but it was too late.

His helmet flew off, leaving him exposed to the full brunt of impact when he landed head first on the shoulder curb, 70m away.

His motorbike broke into two but the damage to his body was even more extreme.

Tan suffered dislocated eyeballs, a torn nose, a broken leg (his right shin was shortened by 1.5 inches), a punctured lung, three broken ribs, a broken spine, and a dislocated shoulder.

His face was smashed in until it resembled, in his words, "a porcelain plate that was dropped on the floor, but held together by my flesh".

Tan also lost half of his brain's capacity when his synapses and brain vessels were damaged.

The doctors gave him less than 1 per cent chance of surviving.

He shouldn't have lived.

Takalah Tan in the hospital after his accident.

Takalah Tan in the hospital after his accident.

Readers might be familiar with Tan, who now goes by the name Takalah.

The now 50-year-old became internet-famous in June 2019 after a Twitter user posted about his chance encounter with the brain-injury survivor.

Aside from a dent on his head and a thin hairless line encircling his scalp, it's hard to tell that Tan had lost half of his brain's capacity.

Image by Andrew Koay.

Image by Andrew Koay.

He is eloquent, active, and speaks just like any other regular person, at times with more gusto.

In fact, Tan seems to be better than most in connecting with people.

Twice during our interview at a HDB estate in Pioneer, Tan managed to strike up conversations with complete strangers, speaking to them as if they were old friends.

Became like a new born baby

Tan tells me that, ironically, his situation might have been worse if his helmet had stayed on 26 years ago.

If he had had it on, his skull might not have fractured and subsequently released the build up of fluid in it, causing even more brain damage.

In total, Tan had seven surgeries performed on his brain and another nine reconstructive surgeries to fix his face and body.

What wasn't cured, however, was Tan's permanent amnesia.

His case was so special that a huge chunk of his hospital bill for the surgery which reshaped his head was foot by the hospital because they used him as a research subject.

He was like a new born baby after the accident, with no "database" to refer to people and no ability to retain memories.

Even with the three months spent in the hospital recuperating, Tan still suffers from short term memory retention deficit.

Takalah suffered from permanent amnesia after his accident. Image by Andrew Koay.

Takalah suffered from permanent amnesia after his accident. Image by Andrew Koay.

It is challenging for Tan who has to resort to recording important things in a notebook.

It works for things like meeting dates and tasks, but not so much for conversations when people throw about random bits of information.

"That's why in a group, people think I'm like an alien. And that's why it's very difficult for me to work in the real world," says Tan who currently does physical therapy for elderly people at Tzu Chi Senior Day Activity Centre in Jurong.

At the centre, Tan finds that he can be imaginative and free to plan his exercises and therapy sessions.

"Old people are interested because they don't want mundane repetitions so it's a good match," he quips.

Tan works at a senior citizen's activity centre today. Image by Andrew Koay.

Tan works at a senior citizen's activity centre today. Image by Andrew Koay.

The loss of his father

Tan's cheerfulness now belies the pain that he and his family went through during darker days.

"When I met with the accident, the police called my home and my mum answered the call. When she heard about my traumatic accident, she collapsed and cried. My dad collapsed on the chair and cried, 'Why must it be my son?!"

Tan's father took the accident hard because the high-achieving Tan was his favourite son.

When Tan was hospitalised, his father gave up drinking to care for him.

Tan senior wanted so much to stay by his son's side that he chose not to go for a much-needed heart bypass.

"He did not want his family to run between two hospitals," says Tan. "That would have been too heavy on them. That was why he called off his own surgery."

Unfortunately, without the surgery, Tan's father passed away from a heart attack in his sleep during the three months that Tan was hospitalised.

Fresh from his accident with no concept of death or memory, Tan could not comprehend the death of his father.

His mother told him much later that when the family was gathered at his father's funeral, he blurted out, "Ma, where is daddy? Why is brother holding daddy's photograph?".

It broke his mother, who felt as if she had lost two men in her life at one go.

Tan could only understand the weight of his father's death six months after his accident. The guilt of it, he says, was a big reason for his suicidal thoughts.

Contemplated suicide

It's hard to imagine what Tan went through after the accident, having lost the first 24 years of his life, and then his father.

Suicide was often on his mind.

"I had thoughts about whether I should live on or should I not. I was glad that I still had the ability to contemplate. After my accident, I felt very lost, I felt alone. People didn't understand me. They saw me though filtered pain, bias, and a narrow mindset. If I was going to remain a handicap, I might as well go."

If he were to go, his loved ones would only feel the pain for a short while. Instead, Tan felt that he should become a dutiful provider if he were to stay on.

Standing outside his flat on the ninth floor, the engineer even calculated pressure differentials and torque in order to ensure a quick and certain death.

After all, one does not jump off a HDB block only to not die but instead become more disabled, he said.

Hard to argue with that.

Lost all memory of who he was

Left with nothing, Tan had to go through his old books and photos, to build an idea of the achiever he used to be.

He learned that he was involved in testing the air ventilation system for a civil defence bomb shelter.

He also designed a device which provided standard deviations of 1 percent when testing the strength of concrete, a huge improvement over the Windsor Probe which had standard deviations of 20 per cent.

This is how it works: The device measured the velocity of a flying bullet when it is shot into a piece of concrete. There, it provides coordinates which measure depth and strength. From this, he gets a curve which improves the standard deviation to 1 per cent.

Tan on a stallion in Australia before the accident. Image courtesy of Takalah Tan.

Tan on a stallion in Australia before the accident. Image courtesy of Takalah Tan.

Tan says that he cannot remember any of these achievements now, but he knows that they are his, by going through his own belongings -- books, poems, pictures, and diary entries.

"I felt proud of who I was. I felt what a great loss to society," he says quietly.

Tan also found out that he was born with asthma, a condition he overcame by running and swimming and in part driven by envy of his brothers who were stronger, physically.

He went on to become a school runner with National Junior College, a cross-country runner, a triathlete who took part in a 100km race to place 36th place in the whole of Singapore, and a Commando.

Tan was a triathlete before his accident. Courtesy of Takalah Tan.

Tan was a triathlete before his accident. Courtesy of Takalah Tan.

During our conversation, Tan asks if he can recite a poem.

His voice booms and ebbs with emotion, seemingly unaware of the passers-by around us:

Against the Wind

Older but not wiser

I still find myself extricably

And unavoidably

Running against the wind

Whilst it could have been easier

Rowing with the tide

Something within me beckons

Do it otherwise

Define instincts rejecting the norms

Living my life on its edge

I refuse to conform

Perhaps one day, just one fine day

When my time is done

Lay down to oblivion

My life has just BEGUN.

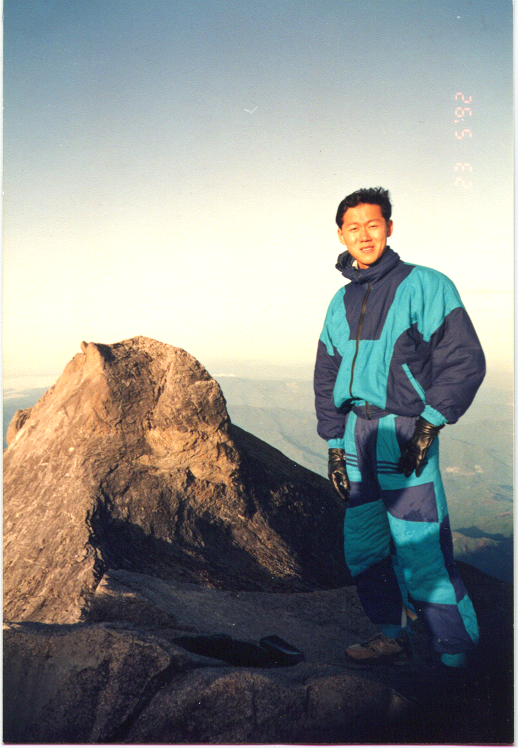

Tan scaling Mt Kinabalu. Courtesy of Takalah Tan.

Tan scaling Mt Kinabalu. Courtesy of Takalah Tan.

Tan wrote it when he was 15 but he does not remember the reason for it.

Despite that, the poem resonates with his predicament and as he recites it, I couldn't help feeling that in a strange clairvoyant twist, 15-year-old Tan might have written it for future him.

"When I found this poem, I said, hey, it's not the end, it's a beginning. So I should not brood or demoralise myself," Tan says.

"The trade off was worth the while"

Tan's decision to live on was in part influenced by a chance encounter with Aleem, a neighbour from the second floor of his HDB block.

"I saw him one day, sat beside him and said, 'Hey not bad, the sun is shining bright. Today is a good day!'" Tan recounts.

"He looked at me with 'blur' eyes and then turned to the front. I saw that he was holding a walking stick, meaning he has a movement disability."

Aleem's mother told Tan that her son had an accident six years ago when he collided with a bus, fractured his spine and became paralysed. A build up of fluids in his brain caused him to become a vegetable.

On the outside, Aleem looked perfectly fine, but he wasn't functioning on the inside.

"He looked good. I looked bad. At that time, I realised the trade off was worth the while. I traded my eye, my sense of smell, my face, my looks, for my thinking ability."

Tan considers himself "fortunate" despite his extensive physical injuries. Image by Andrew Koay.

Tan considers himself "fortunate" despite his extensive physical injuries. Image by Andrew Koay.

A lesser person might have given up but Tan still considers himself "fortunate" especially when he gets to see many other brain-injured people in his support group, many of whom have greater extent of brain dysfunction.

"I'm still able to perceive, communicate, and learn but many of them couldn't. Some of them had semi-lateral paralysis, some of them had holes in their skulls, some of them could hardly talk," he adds softly. "It made me think twice about suicide."

Because of this, Tan has now devoted himself to helping other brain-injured people and takes up leadership roles by organising walks and camps for those in his brain-injury support group.

He speaks fondly of a particular girl whose family moved from Johor to Singapore just to be nearer to NUH where she receives treatment.

Once a bright and helpful girl, she suffered permanent brain damage when she fell from a second floor trying to help a teacher retrieve a lost item.

Tan sees her regularly to provide physical therapy and keep her active.

"Her condition is deteriorating but I want to do my best to help her," he says.

An uphill climb to thrive

It was an arduous journey for Tan to not only get back on his feet, but thrive in life.

Half a year after his accident, Tan found work at his family's Hong Kong dim sum stall at a Suntec City food court.

It was simple enough for him but Tan found that it did little to help rehabilitation. He quit the job after one week.

Then, Tan's friend, a vice principal with a local primary school hooked him up with a temporary job with news agency Reuters' Singapore office where he could do back store room work and earn enough for his own dental realignment and other medical bills.

For Tan, it was a huge step towards being independent.

After spending a year at Reuters, Tan quit to join his brother's courier dispatch company where he learned administrative work like invoicing, billing, and salary.

He also honed his speaking abilities with the Thomson Toastmasters Club for three months until he could articulate his story at a medical forum.

Tan managed to become a relief eacher just six years after his accident. Image by Andrew Koay.

Tan managed to become a relief eacher just six years after his accident. Image by Andrew Koay.

In 1999, Tan even managed to take a half-year teaching course at NIE and become a full-fledged relief teacher in 2000.

To build up his own muscles, Tan hobbled to a nearby swimming pool to practice the horse stance (Chinese martial arts) and exercise his limbs without overstraining them.

When his muscles became stronger, Tan graduated to swimming short lengths of the pool.

These baby steps paid off. Today, he is able to swim the butterfly style and dive the full length of the pool, he says with pride.

Tan tells me that he did receive dirty stares from others during his own rehabilitation, possibly in response to his looks and eccentric mannerisms.

However, he was never self conscious about it.

"The battle is in how I interpret feedback and what I can do about it. I know I'm not normal. No one is normal. Everyone has their form of deficit. It's about being able to make the best of every situation."

I went away from our conversation touched by Tan's tenacity. Few can bounce back with such vigour and zest to not only live, but be a beacon for people, brain injured or otherwise.

What continues to inspire him, even in his dark days, is a particular poster he saw at Peace Centre. In it, a lighthouse shines a beam of light for ships in a dark stormy sea.

He is just like this lighthouse, he says:

"Seemingly useless but serving a dutiful role to prevent ships from capsizing, to prevent people from collapsing because of psychological dilemma or emotional trauma. Whatever menial disability that I have, I can overcome them through adaptation."

I have no doubt that he will overcome and thrive whatever the circumstance.

Top image credit: Takalah Tan and Andrew Koay.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.