Editor's note: Information about the year which St. Nicholas Girls' School was awarded SAP status, former principal Sister Francoise Lee, and the name of the school have been updated for accuracy.

As a Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) Secondary (Toa Payoh) girl who spent a decade in a white blouse, blue pleated pinafore and a shiny flat metal badge, I always viewed myself as an "original" IJ girl.

For those not acquainted with the IJ family of convent schools, the CHIJ Town Convent on Victoria Street (where the CHIJmes building and campus is now — bars and pubs) was moved to Lorong 1 Toa Payoh, where it still is now.

Before or roughly around that time, more primary and secondary schools run by the IJ sisters came up around various parts of Singapore, and we've now got 11.

But I must admit, as an alumna of the "OG" IJ school (founded in 1854), I've always felt an unspoken pride over the other IJ schools.

Of course, this was silly. I find identity with every IJ girl I meet or work with, whether she's from IJTP or Katong Convent or St Joseph's Convent or St Theresa's Convent.

It was only when I was asked to attend a screening of a documentary film on the history of CHIJ St. Nicholas Girls' School (SNGS), though, that I truly realised how this little unreasonable arrogance I had extended institutionally, and all the way into our past — although certainly, language had a big part to play in it.

I'll explain.

The English school & the Chinese school

Even though I have friends from SNGS, I actually never knew it was once one of Singapore's OG Chinese-language schools.

Like the English-language CHIJ Town Convent, SNGS was a home for orphaned baby girls, and gave aid and education to those who were from poor families, but also accommodated daughters of wealthy Chinese merchants.

But what I didn't realise was the second-class treatment the SNGS girls had in the early years of the convent's founding.

I, and likely most people, always knew that CHIJ was located at the Victoria Street campus.

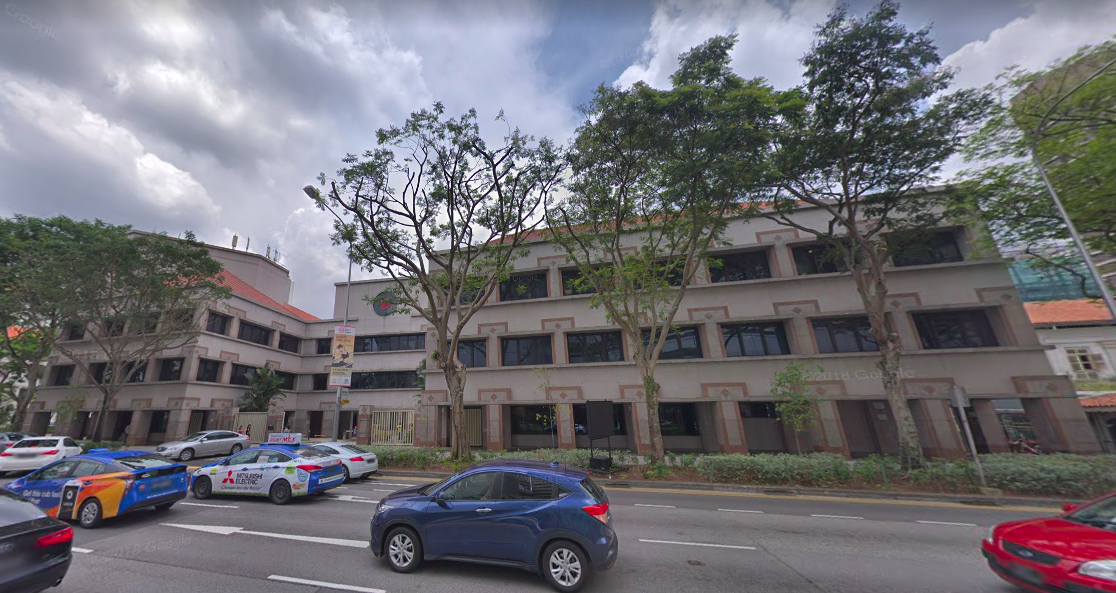

What less people may know, though, is that what was for a time known as the "Victoria Girls' School", two classes of a total of 40 pupils were opened (one for Primary One and one for Primary Two) nearby in 1933, at the older version of this building on 251 North Bridge Road formerly occupied by SMRT and managed by the Land Transport Authority:

Google Street View screenshot circa March 2018.

Google Street View screenshot circa March 2018.

The change in name came during the Japanese occupation when some schools in Singapore had their names changed to reflect the streets on which they were located.

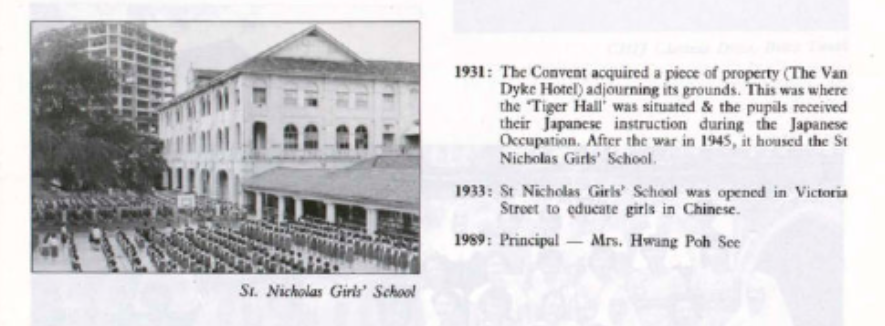

According to SNGS alumna Eva Tang (remember her, she'll be important later), this was the site of the Hotel van Wijk (although in a CHIJ publication it's referred to as the Hotel Van Dyke), which was bought over by the IJ sisters.

It was Sister Francoise Lee, the longest-serving principal, who pushed for an extension of the IJ school to cater to Chinese Catholic girls, and so it was started in the building left behind, formerly apparently a hotbed for prostitution and vice, a risk for moral corruption among the young impressionable girls.

The girls who attended the SNGS/Victoria Street Girls' School (VGS) were from Chinese-speaking families, both disadvantaged and wealthy.

Screenshot via CHIJ publication

Screenshot via CHIJ publication

The war threw things out of whack, but after it ended, the SNGS girls went back to school there. But because the original hotel's buildings were fragile and unstable, and also not enough room for the students — who started spilling over into the corridors of the Victoria Street campus — Sr Francoise led fundraising for it to be torn down and a new school campus to be built in its place.

This effort was successful, and in 1951 it was built. But in 1952, a decision was made to give the new campus to the English school instead, because their population was larger.

The SNGS girls were heartbroken, and relegated to the old Victoria Street campus vacated by the English school.

Unbeknownst to them, though, more challenges lay ahead.

The Communist infiltration

Sr Francoise Lee, played in a documentary-film by an actress. Screenshot via "From Victoria Street to Ang Mo Kio"

Sr Francoise Lee, played in a documentary-film by an actress. Screenshot via "From Victoria Street to Ang Mo Kio"

Singapore then entered a time of political volatility, during the Cold War period.

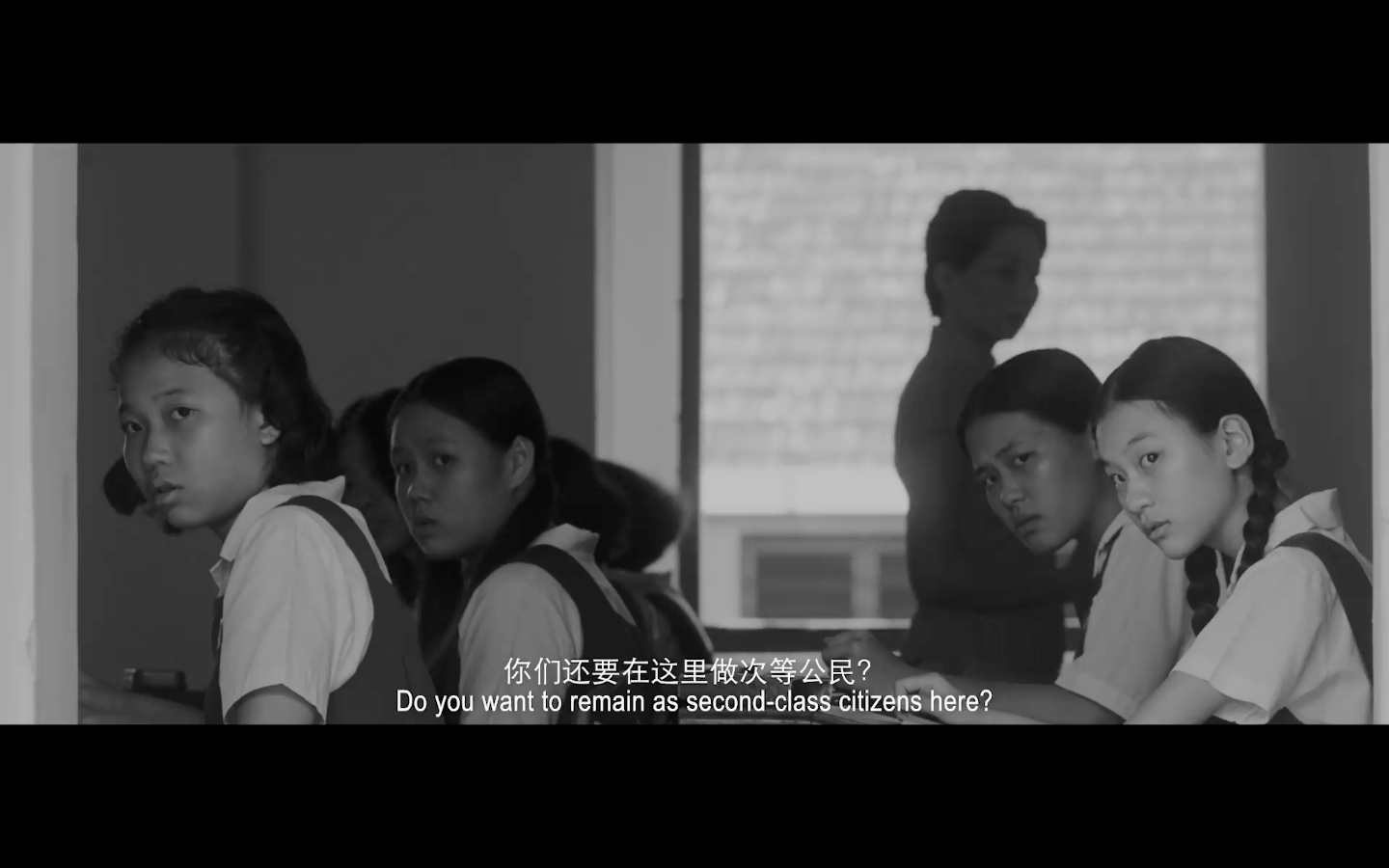

SNGS was not spared — communist female students joined the school and tried to introduce Maoist literature, attempting to convince their classmates that they should move to China and continue their education there.

But the steely Sr Francoise clamped down firmly on it and expelled the girls found to have attempted to impart these beliefs on the students.

Transitioning to an English-first education

Singapore's new leadership (under the late Lee Kuan Yew) also took a renewed focus on teaching all Singaporean students English as a first language, and this transition was very difficult for Chinese-medium schools like SNGS.

Chinese-language teachers at the school who educated students in subjects ranging from math to history and geography felt displaced, almost helpless, at their inability to speak English and convert their curricula and syllabi to a whole different language.

But through the tenacity of SNGS's initial principals — Sr Francoise as well as Hwang-Lee Poh Soh Lee, who saw the school through a combined six decades of its early existence — SNGS successfully transitioned itself into a bilingual school, and in 1979 was awarded SAP (Special Assistance Plan) status.

It is now also widely recognised as the highest-in-standard CHIJ school in Singapore, academically.I'm glossing over a lot of details here, but that's because I learned all of this and more when I watched the documentary-drama film "From Victoria Street to Ang Mo Kio" by Tang (whom I introduced to you very briefly earlier), released in conjunction with SNGS's 85th anniversary.

It tells the story of all these things I shared above, and more — the very real experiences of the girls carrying their classroom tables and chairs from corridor to corridor (in response to changing elements), hopes lifted and dashed with the new campus being taken away from them seemingly without mercy, and the fortitude the girls, their teachers and principals showed over the decades.

Screenshot via "From Victoria Street to Ang Mo Kio" film

Screenshot via "From Victoria Street to Ang Mo Kio" film

The journey SNGS took to finding their Ang Mo Kio campus is one that is told in significant detail by Tang in her film — with its past principals and alumna sharing little, meaningful details like how the girls brought bougainvillea branches to plant in pots to beautify the campus:

Photo via this SNGS publication

Photo via this SNGS publication

to really make the school their own.

But I've given too much away already. Beyond this, I learned a lot from watching the film, both about SNG but also about the IJ Family as a whole, and the experience both enlightened me and made me ashamed of my previously-held pride, also giving me a massive amount of admiration for the seniors who went before me at CHIJ.

And before you think the film will alienate non-IJ girls, I would argue that you could still relate if you went to a Chinese-language school, or a SAP school, or even are simply interested in part of Singapore schools' history.

The SNGS Alumnae Association runs periodic screenings of the film, the details of which they post on the film's website.

Top screenshot via "From Victoria Street to Ang Mo Kio" film by Eva Tang

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.