As I arrive at an east-side HDB void deck on a late Wednesday afternoon, I feel heightened apprehension at the task before me.

It's not because I am interviewing someone prominent, or someone controversial — I am here to meet a fairly normal Singaporean lady in her 60s, who wishes to be known by the fairly normal moniker of Ms Lim.

My unease stems instead from my first meeting with her a few weeks prior, where we discussed the possibility of an interview, which, in turn, made me realise that interviewing Lim is likely to be harder than I originally anticipated.

This is because Lim has Alzheimer’s disease, a form of dementia that sees symptoms of progressive intellectual decline over the years.

A person who has dementia often faces problems with memory, confusion, and changes in mood, behaviour and personality.

Talking in circles

And while her dementia is only in its early stages, the symptoms of Lim’s condition were quite apparent from that first meeting we had.

As we made polite small talk in the quiet cafe we’d met at, I noticed that our conversation was moving in circles.

Her responses to my queries about how her week was going would slowly spiral towards something she had told me a few minutes earlier, and send her back into a looped dialogue that I ended up hearing a few times in those 45 minutes.

The first few times it happened, I thought she was just reiterating a point she was making. But slowly it became more and more apparent, with each repeated anecdote, that Lim had no inkling of the conversational spiral she'd found herself in.

Fast forward two weeks, and I find myself standing at the door of Lim’s flat, wondering how exactly the next hour or so of my life will go.

Will I be able to get through my questions? Will Lim be lucid enough for us to hold a conversation? What's the most polite way to handle her repetition?

When a harsh conversation made her realise something was wrong

My trepidation is slightly eased by the presentation of packet drinks and snacks Lim prepared and laid out on a small coffee table beside the chairs we are sitting on. They were bought specifically for the occasion; a gesture Lim insists on despite my protests.

Real sweet aunty vibes.

At the beginning of our interview, conversing with Lim is just like talking to any aunty.

She tells me about what it’s like to grow up in a large family, her work across different companies, and her compulsion to buy muffins for her friends' children whenever they invite her over to their houses.

It seems Lim lived quite an uneventful life up until the day she found herself on the end of a berating from a friend.

“When I talk to this friend, she will tell me: ‘You say it already you still ask me again?’ You know that kind of (scolding) tone?

‘Huh, you mean just now I just say?’

‘You just say and then you repeated’

But I didn’t know. The problem is that I didn’t even know.”

In this rather coarse fashion, Lim’s friend had made it known to her that she had repeated herself multiple times throughout their conversation.

Living alone may have brought it on — and Alzheimer's in turn increases isolation

Feeling shocked and worried after the incident, Lim consulted a doctor who diagnosed her as being in the early stages of dementia.

“I was shocked actually. My mom just left when she was 94 years old, her memory was super… All my family none of them have the problem, only me.

It could be because I stay on my own.”

I didn’t think much about that last bit at the time. I later learned that one of the risk factors for dementia was social isolation and loneliness, though, and it was then that her words hit home more strongly.

It’s sad to think that at least for Lim, a condition that might have been brought on by loneliness has served to increase her isolation from family and some friends — at this juncture it's worth sharing that a common behavioural trait of someone with dementia is to withdraw from social activities.

She tells me about how she finds going out with her siblings “meaningless”, and that they do not seem interested in knowing about her struggles.

Lim says she also cut off contact with friends whom she fears might have used her mental condition to take advantage of her in the past.

The fight to remember

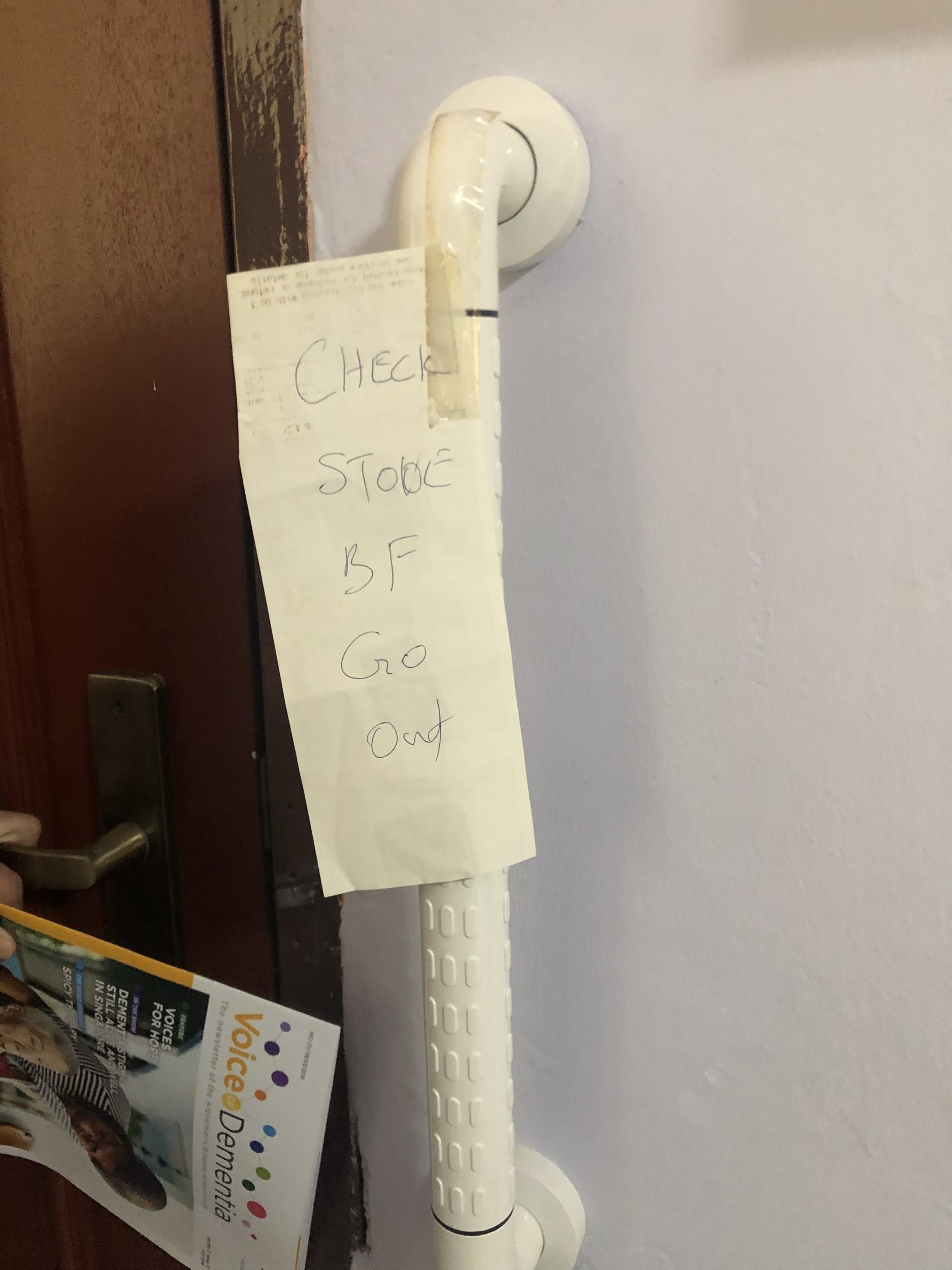

A note scrawled on an old receipt pasted right next to her front door reveals another challenge Lim faces.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

A deteriorating short-term memory can make everyday activities like leaving the house a task and a half.

What Lim calls ”memory lapses” can be as simple as her losing track of what she has done earlier in a given day, or where she is when she finds herself in less familiar places.

Then there’s the prospect of having to engage in conversations with the very real and embarrassing possibility of constantly repeating yourself and coming across as senile.

When I ask her about this, though, Lim is quite pragmatic:

“I have nice friends who will tell me 'this thing you already say'. It shocks me that I keep repeating (myself). So please tell me when I keep repeating my story, because I wouldn’t know.”

Battling the condition

Despite her saying this, though, I’m somewhat ashamed to admit that I never plucked up the courage to tell Ms Lim about any of the multiple times she had repeated herself in our entire conversation.

I did think about it at various points but it just seemed incongruous to interrupt someone who, despite her condition, still carries a relatively high level of self-regard for her own lucidness.

“I know what I’m talking. A person with dementia will be very very disorganised. And the way they speak you know it doesn’t make sense sometimes. But the friends whom I know tell me ‘you talk very sensibly — you know what you’re talking.’ I say ‘yes, I know what I’m talking’. Mine is more of a memory lapse rather than dementia. But this is probably part of the dementia lah, I don’t know.

Now I can be talking to you very logically. But then when you all leave, I cannot remember what actually I’ve said, because it’s a memory lapse.”

While Lim's dementia is still in its early stages, she says she is working hard to slow down the symptomatic progression of her condition.

She attends a weekly programme at a café hosted by the Alzheimer’s Disease Association (ADA).

Here, Lim gets to participate in making simple works of art (something she never enjoyed growing up but recently learned to love), as well as jaunts to museums and the Botanic Gardens.

One of the artworks Lim created at the ADA Cafe. Photo by Andrew Koay

One of the artworks Lim created at the ADA Cafe. Photo by Andrew Koay

Staring down the barrel of an inescapable fate

It’s at this cafe that Lim also gets to interact with others who have been diagnosed with dementia.

“You can tell some of the elderly are really the quite serious type. So when I go there I always look out for those who are worse than me, then I will bring them and say ‘come let’s talk’. You know I’m very talkative. So when I go there you sit down. Then I ask ‘did you take your breakfast?’ Sometimes they don’t remember (laughs). Poor things ah, I haven’t got to this stage yet.”

It’s hard to ignore the horror of Lim’s situation at this point. As you might already know, there is currently no cure for dementia.

And while medication and therapeutic activities can help to slow its progression and maintain cognitive functions, it's unfortunately near-inevitable that Lim’s condition will one day decline to a stage where she will lose all sense of who she is.

At its most severe stage, people with dementia experience no apparent awareness of past or present, require full assistance in activities such as dressing and showering, and can even get ‘lost’ in their own homes.

Does it scare Lim at all then? To be staring down the barrel of what is her inescapable fate?

“I am already mentally prepared. One day I will become like them like that. So I’m trying to… at least to slow it down.

This condition will get worse, it will not get better. I’ve been trying to maintain.”

Her response is accompanied by a defiant smile, carrying a sense of dignity and determination rare in even the healthiest of people.

“I won’t allow this problem to actually overcome me. Even though despite this dementia, I’m still me. And I will not allow this condition to overcome me.”

"Who are you guys ah?"

As the interview winds down to its conclusion and we say our goodbyes, Lim turns to the two people from the ADA who had helped to set up the interview and asks them, "actually, who are you guys ah?"

It's a shocking moment for me, personally, that reveals the harsh reality of Lim's condition — this must be at least the second time she would've met the people from the ADA. They were also at her house talking to her before I had arrived.

Lim also didn't remember the first meeting we had, nor did she remember that I was a writer from Mothership — I had to explain that mid-interview.

I wonder how much of this meeting she will remember, or if she even remembers that her story will be told.

Throughout the two encounters we had with each other, I felt grateful for Lim's openness to me and her willingness to talk to me about her family and her struggles.

Amidst the isolation and social withdrawal Lim is battling, I wanted her to know that I cared, that the ADA people cared, and that we were working towards bringing awareness to the challenges faced by people with dementia by telling her story.

Yet the sad irony is that the one person I want the most to feel happiest from this story is unlikely to know or remember her part in it.

In recognition of World Alzheimer's Month (WAM) 2019, ADA will be holding a carnival on Saturday, September 21 at *SCAPE, open to the public.

Date: Saturday, 21 September 2019

Time: 11am to 4pm

Venue: *SCAPE Singapore

2 Orchard Link Singapore 237978

More information about the carnival can be found here.

Cover illustration by Dan Wong

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.