"People think that Gordon Ramsay is putting on a show but it's real," quips Pamelia Chia as she sips her kopi.

We're sitting together at Heap Seng Leong coffee shop on North Bridge Road in the early morning on a recent Tuesday.

Here, time seems to pass as slowly as the lazy ceiling fan above, the air thick with the scent of coffee and condensed milk. It helps also that our fellow clientele consist chiefly of elderly men quietly perusing their newspapers.

Even though she doesn't live here anymore (Chia is now based in Melbourne, having moved there with her husband), she makes it a point to come here whenever she's back — it is, she confesses, the only place where the coffee does not give her anxiety.

Having worked in three kitchens at the homegrown Michelin-starred Peranakan restaurant Candlenut and the now-defunct Lollapalooza, the 28-year-old is very familiar with what goes on behind the scenes at restaurants.

Working in a restaurant sucks, she says candidly, because in an ironic way, the sense of hospitality one gets from feeding people is not translated into the kitchen.

Pamelia Chia. Image by Rachel Ng.

Pamelia Chia. Image by Rachel Ng.

A "crushing" industry

"It's not what you think it is and sometimes I feel a bit jaded and disillusioned about it and I feel like getting out, to be honest," she says, who currently works at a restaurant called Carlton Wine Room in Melbourne.

Scarfing down canned curry with rice within a five-minute lunch break, a fully-grown man breaking down in the kitchen, and the sound of kitchen machinery triggering heart palpitations in a young cook — these are just a few of many experiences Chia shares with me from her friends about how brutal restaurant kitchen work can be.

Chia counts herself fortunate enough never to have experienced horror stories as bad as these, but she says she certainly struggled in the first six months at Candlenut as a line cook trying to get used to the rigour and high standards there.

A food sciences graduate from the National University of Singapore, Chia was a pastry chef at Lollapalooza before it closed, and so counts her "real training" as having begun in Candlenut's garde manger (cold kitchen), charcoal grill and curries section.

She shares one of her tasks early on was to cut kaffir lime leaves "thinner than a hair" for garnishes:

"I couldn’t get it, and the thing was that I would only have two or three hours to cut everything to expectations. I was doing it again and again — thank God my husband had a kaffir lime tree and I could practise but I felt like dying. It was so difficult."

On another occasion, a mentor held up a can of crab meat for Chia to smell. She gave it a sniff and thought it smelled fine. The mentor told her, however, that it had just the slightest hint of going bad.

"I was like, how do they even know? Holy sh*t, these people are scary, man!" laughs Chia.

Despite the intimidating work environment, Chia stresses how blessed she was for the opportunity to work at Candlenut.

Apart from the opportunity to really cut her teeth in the F&B industry, Candlenut was one of the rare places that treats its staff like, well, humans, thanks to its chef-owner Malcolm Lee.

"Even though the restaurant industry is so crushing, he knows first hand what it means to lose loved ones because of this obsession (with Michelin stars). It pushed him to realise, ok I need my staff to spend time with their families. They can't just sell their souls to my business."

It is one of a few restaurants to implement a four-day work week for its staff, as well as a mandated 30-minute long staff meal every day, says Chia.

And that's why even though she doesn't work there anymore, Chia's launch for a new book, Wet Market to Table, was held at the celebrated restaurant up the hill on Dempsey Road.

A book that teaches you how to shop at the wet market

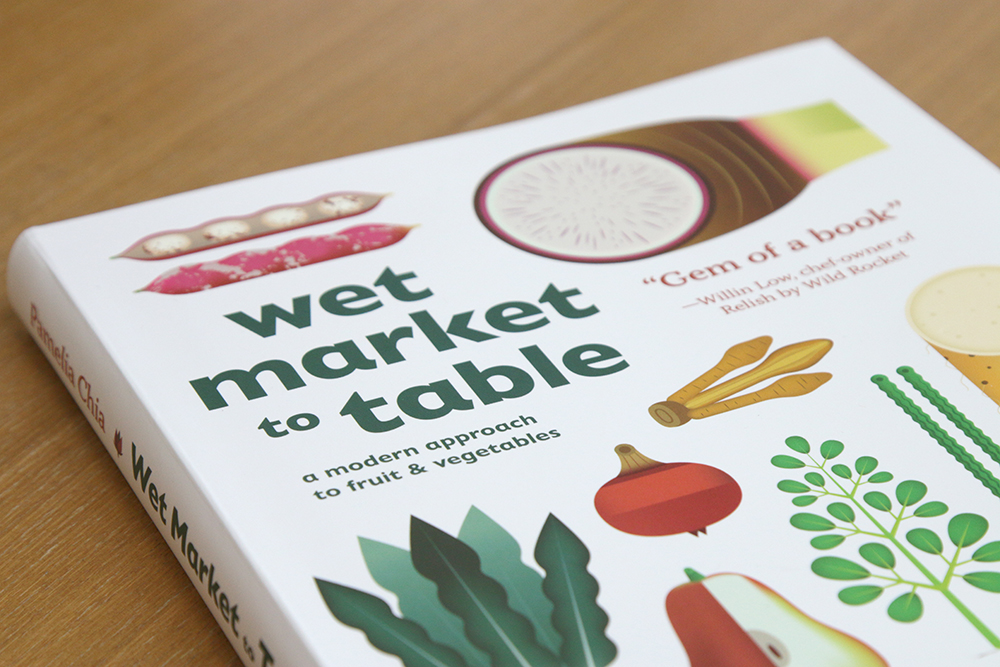

Chia's book is a modern approach to the ingredients you can find in the wet market. Image by Joshua Lee.

Chia's book is a modern approach to the ingredients you can find in the wet market. Image by Joshua Lee.

So yes, what's a chef doing writing a book? Wet Market to Table is a cookbook that teaches readers how to buy and cook with uncommon ingredients that are surprisingly commonly found at local wet markets.

Chia saw this as a creative reprieve from the demands of restaurant work, and in some ways, a story of her twin loves of home cooking and the wet market.

From tatsoi (also known as fu gui cai) to fingerroot (also known as temu kunci), the book, which she first dreamed up about two years ago, offers ideas on how to use these unfamiliar yet readily-available fruits and vegetables from our wet markets.

Chia shows us a large piece of mountain yam in the wet market. Image by Rachel Ng.

Chia shows us a large piece of mountain yam in the wet market. Image by Rachel Ng.

Take mountain yam, one of her 25 featured ingredients, for instance. Chia says it is used by yakitori chefs as it has the amazing ability to imbue minced chicken meat with a silky texture.

And here's another little known fact: Jiro (of Jiro Dreams of Sushi) uses a bit of mountain yam in his famed tamagoyaki.

Chia observed that there was a dearth of information on these local and regional ingredients for the modern home cook.

"When I was at the market I wanted to know what to do with belimbing or buah keluak. There is nothing modern. You just go to Popular, pick up a S$2 book catered to aunties and in the recipes you have things like MSG and chicken stock powder and immediately you're like turned off. I saw a gap in the market. I felt that someone has to write the book and I didn't want to wait for someone else to write it."

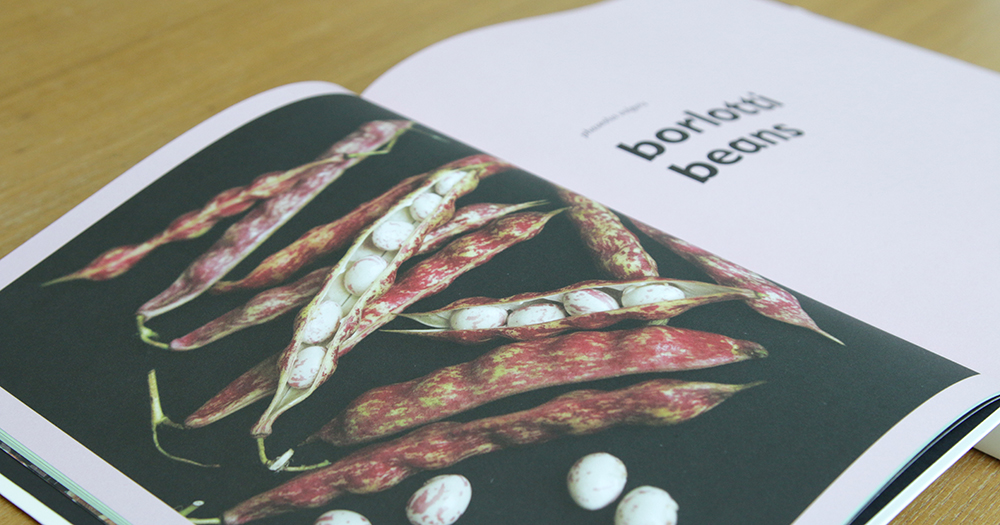

Borlotti beans or 珍珠豆 is one of the ingredients featured. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Borlotti beans or 珍珠豆 is one of the ingredients featured. Photo by Joshua Lee.

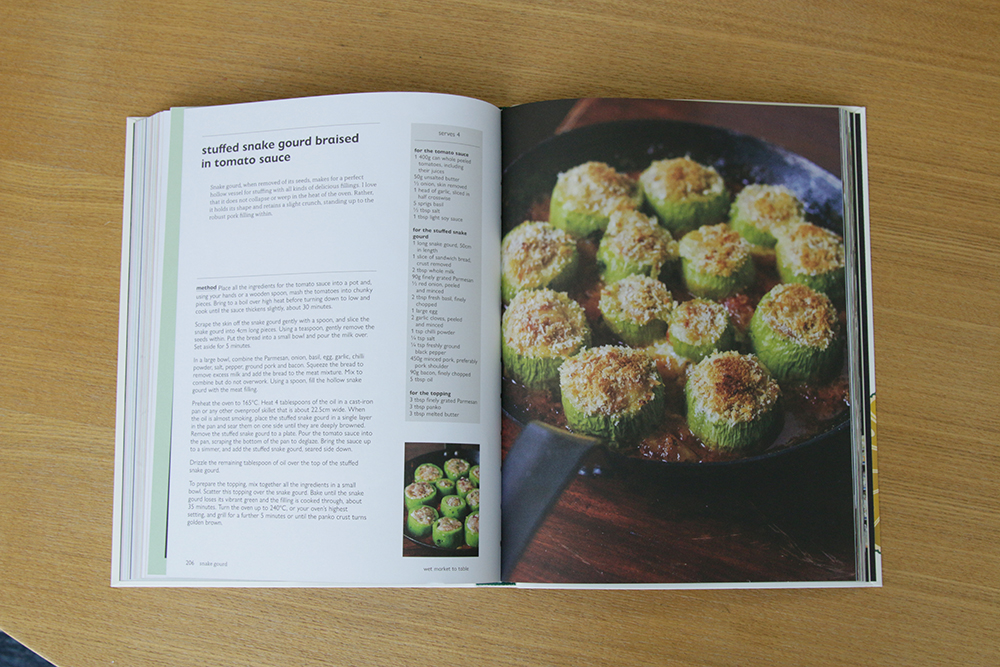

Chia's recipes are modern indeed.

Flipping through her book, you will find a smooth hummus made with borlotti beans, a buttery croissant loaf infused with laksa leaf pesto, and a very tantalising-looking smoked salmon pasta flecked with green dragon vegetable — definitely not your usual home recipes.

For each of the ingredients, Chia covers their various names, their availability and tips on selecting, storing, and preparing them.

Chia's recipes are certainly not common house recipes. Image by Joshua Lee.

Chia's recipes are certainly not common house recipes. Image by Joshua Lee.

Here's where she offers us a pro-tip for shopping at a wet market: Know what you're entitled to.

"When I went to the wet market at first, I didn't know my privileges as a buying customer and I would just say can I get that and they would just bag it up," she says with a slight grin.

That's completely different from what market regulars do.

"They will ask to butcher this, debone that or skin this, so they really get their money's worth," she says.

At the fishmonger's stall, for example, you can ask for a fish to be filleted or butterfly-ed. There is a great deal of versatility and knowledge available in a wet market, which Chia says is one reason why people shop there.

A humiliating experience

And here's another: Don't be a snob.

"When I first went back to the wet markets, I remember it was so humiliating," says Chia with a laugh.

She recounts one of her early trips as a rookie chef to a wet market to buy ingredients for a bouillabaisse (a French fish stew). Armed with a precise list of ingredients down to the last gram, Chia asked for 600g of mussels from the fish stall.

"No 600g. Only 1kg!" said the fishmonger before dumping a kilogram worth of mussels in a bag and demanding S$10.

The first time Chia visited the wet market was a humiliating experience. Image by Rachel Ng.

The first time Chia visited the wet market was a humiliating experience. Image by Rachel Ng.

"I was very affronted! I was like oh my God, so brash. I was not used to it. Growing up, everyone was so civil and then you go to the market and it's very raw and just in-your-face. The uncle was like '小妹第一次煮饭啊 (is this your first time cooking, little girl)?'. Is it inexperience that you don't know that we sell one kilo of mussels??"

It was a stinging experience for the professional cook and for a very long time, Chia did not dare to step back into in a wet market.

But equally embarrassing was her complete lack of knowledge about local ingredients like the roselle and moringa, which her husband, an urban farmer, would bring home:

"To not have your roots as a cook, I find that it's a bit humiliating. If you're unable to be as comfortable with those ingredients as you are with ingredients from the West, then what does that make you as a chef?"

Discovering casual wet market camaraderie & relationships as a child

Chia's experience with wet markets actually goes back to her younger days, when she tagged along with her mother on marketing trips to the now-defunct Lakeview Market at Marymount.

Chia describes herself as a "passive buyer" who watched as her mother bantered and chatted with the various stall owners.

Nonetheless it was an experience that she remembers well, involving the usual slab of char siew she would buy to nibble on and the fishmonger who would call her "Assam Fish" affectionately because she loves eating assam pomfret.

"It's very interesting because it's a very casual relationship," Chia adds.

"They might never know your name in real life but they just know you by your face, by what you like to eat, and I think there's that 人情味 (human touch) that you can't replicate in a sterile setting like the supermarket. It's a very natural thing."

But wet markets are disappearing

There are 83 wet markets in hawker centres operated by the National Environment Agency (NEA) or NEA-appointed operators at the moment.

Sadly, though, the number of customers who visit wet markets has been dwindling. A 2018 NEA survey found that only 39 per cent of Singaporeans visited a wet market in the preceding 12 months.

And this isn't surprising, to be fair — wet markets just don't appeal to the young because of the better sanitation, air-conditioning and clearer pricing that supermarkets bring.

While Chia understands this phenomenon, she cannot come to terms with it. She tells me about a time she went online to find out what Singaporeans think about wet markets:

"There was this person from RJC (Raffles Junior College) who wrote something that was quite shocking: the government should abolish wet markets because they don't fit into our clean and green image. I was so angry! Why is it that we put on this sanitised image and eradicate parts of ourselves that seemingly don't fit?"

The unfortunate thing is, though, it does seem like wet markets are destined to disappear eventually.

"Sometimes it's the physical thing that remains and the spirit that disappears. We really have to think about what is important about wet markets and what exactly we want to retain," says Chia.

Can wet markets appeal to a generation of supermarket shoppers?

The wet market way of life, like the habit produce sellers have of hanging their drinks by the side of their stalls, is a product of its time. But other things like the vast knowledge, the casual, longtime human interaction and relationship-building should be retained.

Chia also believes that the Singaporean wet market should also keep up with technology to appeal to a new generation of local grocery shoppers.

And in some ways, that's already happening.

Chia says her mother, for instance, noticed that some supermarkets like Sheng Siong have in-house fishmongers.

She also tells me about 34-year-old Jeffrey Tan, who runs a place called Dish The Fish at Beo Crescent Market.

At his stall, the young fishmonger vacuum packs his fish for customers so it's easy to handle, offers a WhatsApp subscription service that updates regular customers on the latest catch, and also conducts cooking classes to teach people how to prepare certain types of fish.

Singaporeans should be proud of our regional produce

There are many reasons why people might cook with ingredients from the wet market.

Many do it because it is cheaper. Others do it in the name of sustainability (if you think about it, buying at the wet market is the OG way of buying only what you need).

For Chia, it is a pride in the rich produce our region has to offer — a feeling unfortunately not shared by many.

"A lot of the restaurants that have this talk on 'local' are fake. Sorry to burst your bubble," she says with a laugh. "A lot of these restaurants that say that they support regional or local ingredients — when you look at their menu, there’s a lot of imported produce, and then for garnish, a few local flowers. It's not coherent."

However, there are a few that do do so with aplomb.

For Chia, cooking with local ingredients stems from her pride in them. Image by Rachel Ng.

For Chia, cooking with local ingredients stems from her pride in them. Image by Rachel Ng.

Her eyes brighten at the mention of Mustard Seed, a fusion restaurant at Serangoon Gardens.

She rattles off a series of dishes: Prawn hor fun with a sauce inspired by the famous Kok Seng Restaurant sauce, nasi ulam ochazuke which features nasi ulam in yong tau fu broth, a market vegetable salad inspired by gado gado.

Chia says it is her responsibility as a writer and cook to help broaden people's imagination on our local ingredients and inspire pride in what we have in our wet markets.

She relates an anecdote she heard from her former boss at Candlenut to illustrate this point.

"Malcolm was doing a food festival alongside other restaurants. His dish was very simple, crab curry and steamed rice. The other restaurants were doing things like espuma (foam), sculptures, molecular gastronomy, bak chor mee that is not a bak chor mee, things like that.

And at the end of the night, all the chefs finished their day's work and they were all starving, they didn't go eat at the espuma or whatever. Malcolm told me that all of them came to his stall and they were just stuffing their faces like little boys they were like, wah rice ah shiok! They started like pouring the curry and stuffing their face and everything was gone.

And he was like, that moment really cemented what he is as a chef. It's being very quietly proud of what you have as a nation, as a region and being confident."

Almost made me want to hightail it to my neighbourhood wet market to start seeing what I could learn too.

You can get a copy of Wet Market to Table from Epigram here.

Top photo by Rachel Ng.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.