Singaporean potter Kim Whye Kee and I are making small talk when a vase is unveiled before us, immediately stealing his attention away from whatever superficial question I must have been asking him.

“Oh my god!” exclaims Kim, 39, as renowned Singaporean artist Henri Chen KeZhan places the vase on the table in front of us.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

It features mountains and waves painted against a yellow backdrop, flowers descending from red rays. On top, acting as a lid, is a brown boat, riding a crashing wave.

The vase, they explain to me, was made by Kim and exhibited at a prison art show that Chen attended at the tail-end of 2007. It was the stand out artwork of the event.

It was that day, and this vase, that Kim believes “engineered” his life up till today.

Having been in and out of jail over a decade preceding that art show, the former gang leader — who had previously described for Mothership in vivid detail the pain of getting caned — has now rubbed shoulders with a (very) senior minister, attained a Bachelor degree in art, and held his own solo show exhibiting artisanal crafted tea wares, apart from helping and journeying with younger people-at-risk.

Now for the next part of his story: breaking away from his ex-convict label and becoming a fully-fledged ceramic artist in his own right.

From therapy in prison to a full-time job

That this is Kim’s latest challenge is incredible when you consider that just over 10 years ago, art was just a form of therapy for him.

“I took pottery during the last three months of my imprisonment right after my father passed away. I didn’t want to think about it (his father's death) — I just shut off.

You just want to go back home, have a simple dinner and tell your dad ‘I’m sorry. I don’t want to go back to the gang, I just want to be with my family’. But that thing will never happen again because he’s gone already. No matter what you do, how you pray, whatever sh*t — there’s no next time. ”

To distract himself from the pain of losing his father, Kim threw himself into the art form, spending every day and every hour he could in the pottery club.

While other inmates were satisfied with making basic ceramic items painted simply with one colour, Kim would painstakingly refine his work, beautifying it by painting different designs on the façade of his creations.

Inspired by his family, and eager to make amends, Kim eventually designed and crafted a vase that represented the journey his ancestors took from China to Singapore — the boat-shaped lid to the vase a visualisation of the bumboats they would have travelled on.

Made with "some thoughts and feeling"

Recalling his thoughts when the vase first caught his eye, Chen — himself an internationally acclaimed abstract ink and wash painter — says:

“I found that this person (who made the vase) isn’t just doing it for the sake of doing it. He did it with some thoughts and feeling.”

Chen then told another attendee at the prison art exhibition, Jane Ittogi — the wife of now Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam — his opinion that Kim had the potential to be an artist, before buying the vase for his personal collection.

In 2008, after he was released from prison, Kim was taking part in a Yellow Ribbon art exhibition at the Botanic Gardens when Ittogi approached him.

“One lady came to talk to me. She introduced herself as Mrs Tharman and asked me where I lived. I told her Taman Jurong. She said ‘Great! My husband is an MP (member of parliament) there. Why don’t you come and help us.’ So the following Monday I went along to the Meet-the-People Session.

I wore long-sleeves (to cover up my tattoos), of course. I was scared. But then Tharman said ‘Just be yourself’. So the following Monday I just wore a T-shirt and started to interview residents. And then (Ittogi) introduced me to (Chen).”

Chen subsequently invited Kim to his house in 2009 to help him with inspecting and restoring two antique ceramic vases. He knew that Kim was interested in pottery and wanted to get a better feel of where the former inmate stood as a potter.

“I already knew a bit of his history (of being a former gang leader), and of course I’d seen his work before,” says Chen.

“I talked to him, and I felt that he was actually quite serious about learning and doing art, so I was very happy. I asked him to try and do different techniques (on the antique vases).

Frankly, asking him to help to restore the ceramics was an excuse. I just wanted to see him, and see how he can talk about (the ceramics), and how he feels about it… Also, I wanted to understand him better.”

"What the f*ck is a portfolio?"

Unbeknownst to Kim, Chen — who has since the late 80s been helping artists through various programmes — had intentions of giving him a leg up in his budding art career by sending him to school.

It came as a complete shock to Kim when Chen then asked him if he wanted to go to LASALLE.

“No (it wasn’t on my mind), because I was poor. I mean going to art school is so expensive, I can’t even… and my angmoh is damn jialat one.”

But English wasn’t the only thing Kim would need help with. One week before his LASALLE admissions interview, Chen called Kim to check-in on how his preparations were going.

“He asked me ‘How’s your portfolio?’ I said ‘What the f*ck is a portfolio?’ I didn’t understand the term ‘portfolio.’”

The next day, Kim went over to Chen’s house where he spent four hours learning how to sketch. He would continue sketching incessantly over the next few days, getting good enough that when he submitted his portfolio, the interviewer thought that Kim was a “laojiao” (an old hand) at drawing.

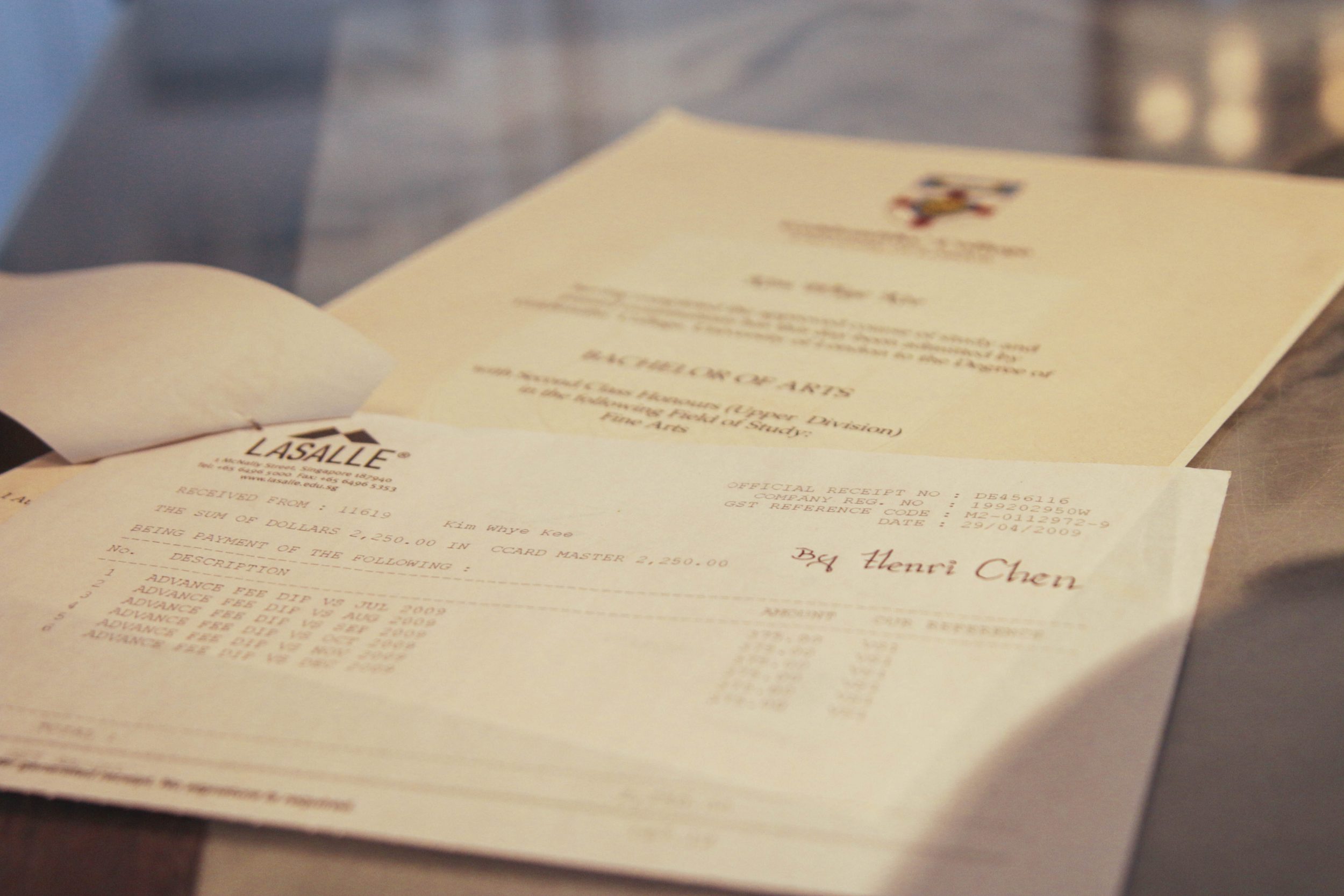

“I passed the interview, but the next thing was the school fees. Woah, it was like too expensive. One semester is already S$2,000 plus and I didn’t know what to do. So I called (Chen) again. He said ‘Just go to the office now’. So I go to the office and (Chen) came, just took out his credit card and that’s it.”

The receipt from Chen's payment of Kim's first semester of tuition fees. Photo by Andrew Koay

The receipt from Chen's payment of Kim's first semester of tuition fees. Photo by Andrew Koay

And so less than six months after first meeting Ittogi at Botanic Gardens, Kim found himself taking classes at LASALLE College of the Arts.

Tuesdays with Henri

It wasn’t an easy ride, though, of course.

Kim tells me how as a former drug addict it was tough being around other students who would take drugs. More than that, he found the rigour of studying tough to adjust to.

“My English was damn bad. It's like every time they asked me to do a presentation for 15 minutes, I cannot one. Open one slide, ah, and I will be like ‘This artist hor… Last time hor…’

So I nearly failed my first semester. I had to resubmit my work. And slowly the lecturer and even Tharman told me not to be worried. Because I was helping him in his constituency doing a lot of follow-up cases, he told me to just keep writing, and they would help me to correct my grammar. And I can learn from there.”

Chen and Kim, with Kim holding his graduation certificate. (Photo by Andrew Koay)

Chen and Kim, with Kim holding his graduation certificate. (Photo by Andrew Koay)

Chen would also continue to help Kim, guiding him through his time at LASALLE until graduation.

“Whenever I face a lot of art projects that I didn’t know how to do, I would just call (Chen), and he would say ‘just come up’. We’ll drink tea and just discuss it.

We would meet up quite often. Every time I felt like I cannot already ah, I would just find any excuse to come and talk to him. And he would say ‘just come up and talk.’ And after that, when I feel better, I would leave.”

From shunning to discovering a passion for tea

These tea sessions with Chen provided more than just advice for Kim to get through school. They eventually brewed an interest in Kim that would come to influence his professional career greatly.

“Last time when he sipped the tea, he would say ‘ugh I don’t want, I want a beer’,” said Chen. “But I said ’Try!’ You know, and he would keep drinking. Now he’s an expert on tea!”

Kim can’t help but laugh and corroborate Chen’s account:

“It's like every time I come (to Chen’s house), he’ll serve tea, serve tea, serve tea, until I dulan already ah. No choice, have to start to learn how to drink tea.”

He tells me that his work as an artist today — which consists mainly of crafting artisan tea wares — is inspired by “how tea brings people together”.

“I think alcohol or drugs or whatever — we take to forget about something. But when we drink tea, it's about remembering. People drink tea to get a clear mind so we remember… so slowly I start to appreciate tea through (Chen).”

A range of teacups and pots made by Kim. (Photo by Andrew Koay)

A range of teacups and pots made by Kim. (Photo by Andrew Koay)

"Art is really for sharing"

Yet, when I ask Kim to describe the most important thing he’s learned from Chen, neither tea expertise nor artistic nous seems to be at the top of his mind.

Instead, he describes a recent trip he took to Penang to find rare wood and gas firing kilns utilised in the crafting process some of his tea wares go through.

“I noticed that (the locals) have the facility, they have the skills. But they just don’t know what to do with the skills… A lot of people in Penang drink tea, but they just don’t know how to make tea ware. So I go there, and did firing, and I shared with them (how to make tea ware). And they were grateful.

Then I started to understand, that what (Chen) did for me, actually, I can carry on one… Art is really for sharing. Whatever we learned from other people or the world, belongs to the world. It’s not meant for ourselves.”

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

The sharing doesn’t stop there.

At his next solo show on September 1, Kim is donating his tea wares to Chen’s private non-profit organisation, Temenggong Artists-In-Residence (Temenggong). The proceeds from the sale of the tea sets will go toward funding the organisation's programmes.

Shedding the "ex-convict" label

It's a gesture — moving from beneficiary to benefactor — that perhaps brings Kim another step closer to finally shaking the ex-convict label that’s followed him through his career thus far as an artist.

“It’s actually been a benefit to me. It's like I’m an ex-con, I’ve been to prison for 10 years — it’s the super best marketing story anybody ever has. I can just keep using that story to sell my work.”

But now Kim is ready to shed what may have previously been a crutch. In fact, he’s been ready since last year.

“My partner kept nagging at me. She said ‘What ex, ex, ex? No need to use the ex already. You want people to buy your work because your work is good. Not because you’re an ex-offender.”

Chen can’t help but nod in agreement.

As all eyes in the room return to Kim’s vase — the one that kickstarted Kim's journey — it's impossible to miss the contrast it has with his latest tea ware.

They were all created by Kim; yet if you ask Chen, it was two very different people who made them.

“In short, this vase is an inmate's art therapy piece, and this tea ware is an artist’s work,” says Chen.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Kim's tea wares will be on show as part of "A Tea Journal", an exhibition organised by the Temenggong Artists-in-Residence.

Date: September 3 - 8, 2019

Opening hours: 12 - 6pm

Location: 22, 24, 28 Temenggong Road

Top photo by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.