When the BKE opened in December 1985, it brought much sought after convenience for motorists.

The 11km-long, six-lane expressway connected Woodlands to the Pan-Island Expressway (PIE), near the Singapore Turf Club.

Before the BKE was built, anyone trying to get to Woodlands from central Singapore would have to travel the length of Upper Bukit Timah Road, passing through Bukit Timah, Bukit Panjang and Choa Chu Kang.

This journey would take around 30 minutes.

The BKE offered an alternative, cutting the travel time by 20 minutes and providing a more scenic drive through the rainforests that dominated the centre of Singapore.

However, this shortcut came at a cost beyond the S$155 million spent to build it.

Cut off

In an article in The Straits Times (ST) poignantly entitled "Is the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve slowly dying?" and published in March 1985, seven months before the BKE opened, conservationist conveyed their concerns about the primary forest.

Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (BTNR) appeared to be drying up, they said.

For some reason, large trees that provided shade to the forest were falling, resulting in gaping holes in the canopy through which sunlight pierces.

With more sunlight peering through, conditions in the forest become drier.

Bit by bit, Bukit Timah's flora was being replaced by weedy plants that thrived in such conditions, and the forest patch may be too small to regenerate itself.

The BKE only served to make things worse, further isolating the reserve from the main water catchment area, the newspaper wrote.

Ivan Polunin, a British medical doctor and documentary filmmaker, told ST then that while there was an existing pipeline which cut off BTNR from the general catchment area, smaller creatures like the Flying Lemur could still cross it.

According to maps from 1983, a 'motorable' track also run between BTNR and CCNR.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

"Now, with a big, broad highway, it's just not possible," Polunin told the paper.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Though Bukit Timah had already been bounded by urban areas, quarries and roads since as early as 1860, BKE sealed the forest in.

Plans to build the BKE was first put forth in 1980. It was suggested then that the expressway would, on paper, remove 86 hectares of forest land.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Image via NLB SpatialDiscovery.

Representations to seek alternatives to the planned route were rejected.

The construction of the BKE and the isolation of BTNR was a "major event in the biological history of the BTNR", National Parks Board (NParks) researchers noted in 2019.

With the forest patch isolated, it was near impossible for wildlife populations from other habitats to reach it.

This impeded the flow of not just natural resources, but also genetic material, risking the genetic health of wildlife populations in BTNR.

"[This] was followed by demonstrable local extirpations, for example of the monkey Presbytis melalophos; though not causing the loss, when the last individuals died there was no source population available to supply recruitment and no route for recolonization of the reserve."

Wildlife which attempted to cross the expressway found themselves at a lethal crossroad.

Screenshot of The Pangolin 1988 edition, volume 4.

Screenshot of The Pangolin 1988 edition, volume 4.

Between 1994 and 2014, there were two Sunda Pangolin deaths recorded each year on the major roads surrounding the nature reserves.

Reconnection?

For nine years after BKE, the BTNR was left boxed in.

In 1994, an effort to formally inventorise the flora and fauna of Singapore was undertaken by the National Council on the Environment (now called the Singapore Environment Council).

It was in this biodiversity catalogue that the thought of reconnecting BTNR with CCNR surfaced, though with a tinge of pessimism.

In a contribution to the publication, botanist Ian Mark Turner noted at length the impact of human activities on the forestlands of Singapore.

Turner was then a staff at the Department of Botany at the National University of Singapore, as attributed in the publication.

At the end, Turner suggested an idea for mitigation:

"A final possibility worth considering is the development of corridors linking the important forested areas

....

Bukit Timah Nature Reserve was severed from the Catchment Area by the development of the Bukit Timah Expressway. The highway makes it impossible for many animals to move between the two areas of forest. In theory some sort of link between the two could be made, though it would be difficult to guarantee that the animals would use it."

In 2001, National Park Board's then-deputy chief executive officer Leong Chee Chiew highlighted the ecological impact of BKE.

"Dispersal of seeds and animal migration is disrupted, resulting in a faster rate of extinction of species," Leong was quoted as saying in now-defunct publication Project Eyeball.

"However, NParks officials are here to mitigate the problem by being pro-active and helping nature along," Leong commented.

Indeed, both Turner's and Leong's comments foreshadowed a grand project.

Bridge

In 2005, Turner's suggestion to bridge the divide between forest lands surfaced again, this time more publicly.

That same year, Nature Society President and Nominated Member of Parliament Geh Min asked the Minister for Transport in parliament if there were plans to restore the continuity between BTNR and CCNR.

The response? "No plans," then Minister for Transport Yeow Chee Tong replied.

However, behind the scenes, the wheels for reconnection were already turning.

Ideas for an infrastructure to facilitate wildlife movement across the BKE was put forth during public consultations for the Singapore Green Plan 2012.

Feasibility studies were carried out, and possible locations and designs were identified.

20 years after BTNR was boxed in, the time was now ripe to reconnect it with its hinterland to the east.

“With the awakening of a fresh generation of Singaporeans towards environmental issues, I felt that it was the right time in 2005 to suggest making restitution for the broken link," former Chief Executive of NParks, Kiat W. Tan, told ST in 2015.

In the years after 2005, optimism for a reconnection slowly grew as anticipation for a decision simmered.

S$17 million

Then, in 2010, it happened.

The Land Transport Authority called for a tender to design and build a 50-metres wide bridge across the BKE for wildlife.

The tender was eventually awarded to local engineering firm Eng Lee Engineering, whose S$11.8 million proposal outbid six other firms.

A year later in July 2011, construction officially began following a groundbreaking ceremony.

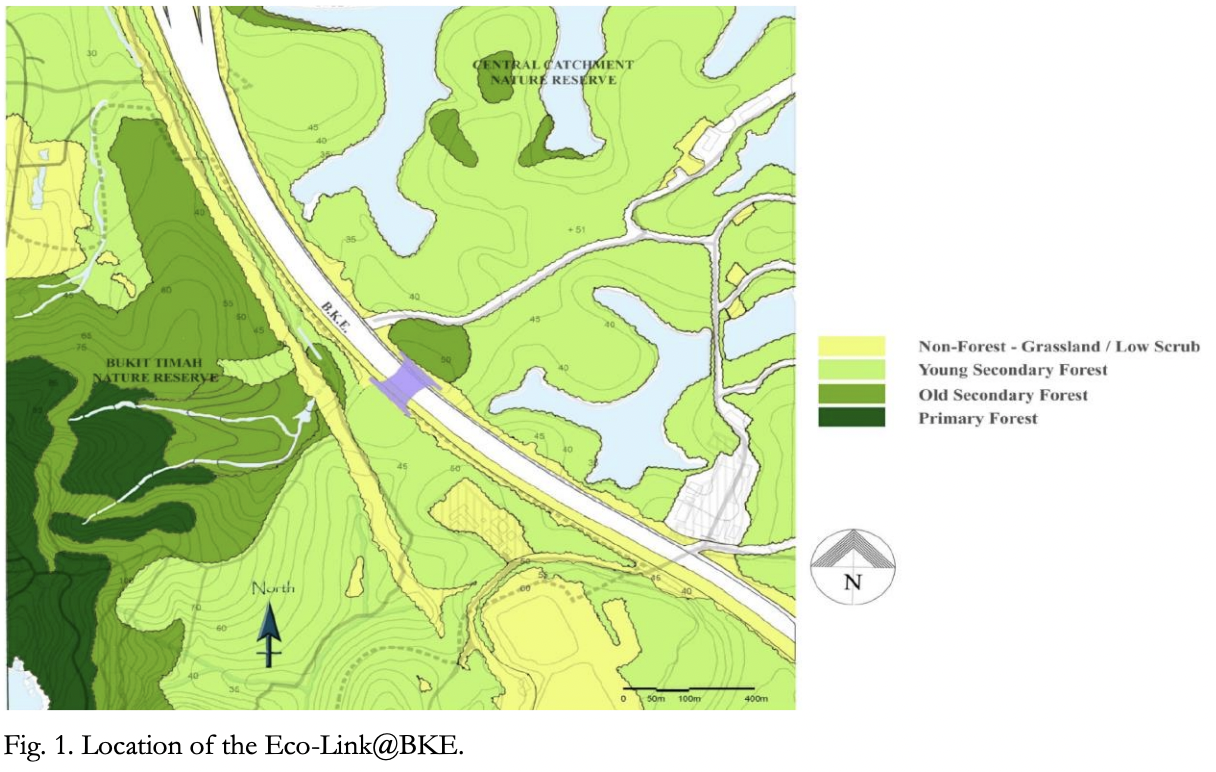

The site for the bridge was deliberately chosen due to the presence of knolls on either side of the BKE.

Screenshot via NParks' "Handbook for Habitat Restoration".

Screenshot via NParks' "Handbook for Habitat Restoration".

The bridge was to link the two high points, and was touted as the first of such ecological corridors in Southeast Asia.

"Eco-Link will be a forest habitat in itself," NParks envisioned in a press release.

"When ready in 2013, populations of native animals such as flying squirrels, monitor lizards, palm civets, pangolins, porcupines, birds, insects and snakes, will be able to travel between the nature reserves to find other food sources, homes and mates. This will also help plant species to propagate by way of pollination and dispersal by the animals.

...

Eco-Link will not only benefit wildlife, human visitors will also be able to enjoy guided walks. For the first few years, it will be restricted to the public while ecological monitoring is conducted to assess its effectiveness as a wildlife corridor. When ready, NParks will consider public access in the form of guided walks on the bridge and the areas around it."

Adding up construction, survey, research and planting works, the Eco-Link project totaled S$17 million.

Turning it green

After two years of construction, the Eco-Link was finally complete, and the link between BTNR and CCNR was restored.

However, Eco-Link's construction was only the start of reconnection.

For animals to want to use the bridge, it has to feel like a part of their home.

In 2013, efforts to realise that forest habitat vision on the Eco-Link@BKE was launched.

Representatives from various agencies and organisations gathered on the bridge to kickstart the greening effort, beginning with the planting of 50 native tree saplings.

Photo via Desmond Lee/Facebook.

Photo via Desmond Lee/Facebook.

50 grew into 3,000, forming the foundations of the forest habitat atop eco-link.

To ensure the flourishing of the greenery atop the eco-link, a strict maintenance regime was adopted by NParks with grass cutting taking place once every two weeks.

"This ensured that the fast-growing turf grass would not compete with the young native plants for nutrients," NParks detailed in its "Handbook on Habitat Restoration".

Eco-Link@BKE, 2013. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2013. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2014. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2014. Photo courtesy of NParks.

By April 2014, Sunda Pangolins and the Common Palm Civet were detected on the bridge by camera traps.

Sunda Pangolin. Image via NParks.

Sunda Pangolin. Image via NParks.

Common Palm Civet. Image via NParks.

Common Palm Civet. Image via NParks.

The bridge became somewhat of a novelty, and people had reportedly been caught trying to access the restricted area.

For awhile, NParks ran guided tours for people to visit the bridge, the first of which began in 2015.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2015. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2015. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Two years later in 2017, these tours were stopped in order to limit human impact on the bridge, a move celebrated by conservationists.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2017. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2017. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2019. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2019. Photo courtesy of NParks.

10 years since

10 years after its completion, Eco-Link@BKE now looks like a hanging garden growing above the BKE, providing wildlife with an elevated safe haven to ford the expressway.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2023. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Eco-Link@BKE, 2023. Photo courtesy of NParks.

Gif via NParks.

Gif via NParks.

Has Eco-Link@BKE prevented human-wildlife collisions along BKE? Not entirely.

Wildlife continue to be spotted crossing the BKE in recent times.

Sambar deers were sighted on the motorway in 2019, 2020, and 2022. In some instances, they became roadkill.

However, based on comments by NParks' officials, the number of incidents have gone down.

NParks' Director of Conservation Lim Liang Jim told ST that between April 2014 and April 2023, "only one pangolin was killed by road traffic".

Lim added in his comments to ST that between 2015 and 2022, NParks recorded "about one roadkill incident per year involving other wildlife in the area", like macaques and wild boars.

100 unique species of bridge users

As of 2021, around 100 species of fauna have been recorded to have used the bridge to cross the BKE.

Between 2018 and 2021 alone, 31 unique fauna species were sighted by camera traps.

These includes, butterflies, birds and mammals, such as:

- Dubios Bar Flitter

- Red-crowned Barbet

- Cream-vented Bulbul

- Horsfield's Flying Squirrel

- Malayan Colugo

- Sunda Slow Loris

Horsfield's Flying Squirrel. Gif via NParks.

Horsfield's Flying Squirrel. Gif via NParks.

Malayan Colugo. Gif via NParks.

Malayan Colugo. Gif via NParks.

The meek Lesser Mousedeer was found to be a frequent user of the bridge, with at least one camera trap record every month for eight months in 2021.

In 2018, the small creatures were only recorded in four out of 11 months of camera trap observations.

NParks also shared that the Lesser Mousedeer was captured on camera traps in BTNR for the first time in 2021, having previously been observed only in the CCNR.

Lesser Mousedeer (Tragulus kanchil) captured on a camera trap at Eco-Link@BKE. Image courtesy of NParks.

Lesser Mousedeer (Tragulus kanchil) captured on a camera trap at Eco-Link@BKE. Image courtesy of NParks.

Lesser Mousedeer (Tragulus kanchil) captured on a camera trap at BTNR. Image via NParks.

Lesser Mousedeer (Tragulus kanchil) captured on a camera trap at BTNR. Image via NParks.

"The Eco-Link@BKE is a good example of how habitat restoration has supported our native biodiversity," Minister for National Development Desmond Lee wrote in a Facebook post.

Since Eco-Link@BKE, two more wildlife bridges have and will be built here: one in Mandai and another upcoming one across Upper Bukit Timah Road.

Mandai wildlife bridge, completed in 2019. Photo via NParks.

Mandai wildlife bridge, completed in 2019. Photo via NParks.

Wildlife bridge over Upper Bukit Timah Road, to be completed in 2026. Photo via NParks.

Wildlife bridge over Upper Bukit Timah Road, to be completed in 2026. Photo via NParks.

Like a thread connecting fabric, the Eco-Link@BKE is an attempt to piece together two forest patches divided by the needs of development.

In 1994, a concluding thought in a chapter of a book left open the question of whether such a retroactive solution would be effective.

Turner left Singapore around 2004 to return to the UK, just a year before the public consultations for a wildlife bridge were launched.

He is now the Singapore Botanical Liaison Officer at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, working on the flora of Singapore and helping other contributors to the flora in obtaining information from the collections at Kew.

Reflecting on the 10th anniversary of Eco-Link@BKE, Turner shared with Mothership that when he first made the suggestion of a wildlife bridge in 1994, he did not think it would actually happen.

"But it has happened, and seems to be working. This is good news for Singapore and good news for the conservation of biodiversity in and around urban areas in the tropics."

Top image via NParks.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.