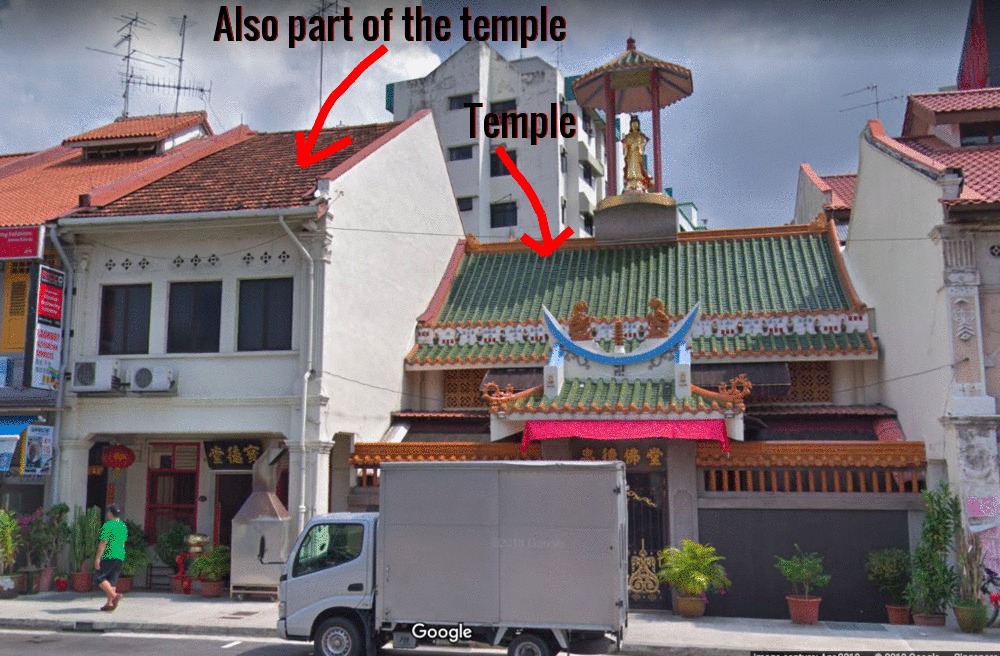

If you stood across the street from a certain stretch of Geylang Road, you would notice something interesting about unit number 475:

Screenshot via Google Street View

Screenshot via Google Street View

It happens to be the temple tucked some way in from the rest of the shophouses lining the road — notice in particular how its façade starts further in than the others.

(By the way, specifically these two buildings constitute what the Chong Tuck Tong Temple is today:

Yep, that brick-roofed, white-painted house to the left of the temple is also part of the temple now. It's called Bao De Tang. (Screenshot via Google Street View)

Yep, that brick-roofed, white-painted house to the left of the temple is also part of the temple now. It's called Bao De Tang. (Screenshot via Google Street View)

But we digress.)

Interestingly, it's the same story in the alley behind the temple:

Notice the "depression" in the double yellow lines drawn along the road demarcating government land vs private property. Photo by Jeanette Tan

Notice the "depression" in the double yellow lines drawn along the road demarcating government land vs private property. Photo by Jeanette Tan

There's a reason for this, explains Alan Chong, the young man we are here to meet — we'll explain in a bit why it is here we are meeting him.

Fire, the presence of a roof, and government land

To understand this properly, it's worth relating a brief part of the history of this once Taoist-only but now both Taoist and Buddhist temple.

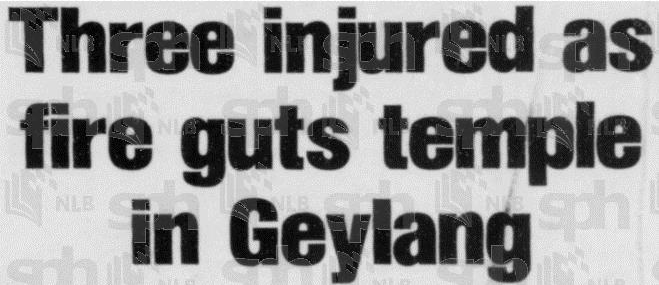

It originally was built flush with the front and rear of the rest of the shophouses along the road, but in 1989, an electric short-circuit in a toilet sparked a massive fire that burned down almost the entire original building, including part of its roof on both sides.

Photo via NewspaperSG. Click image to read article

Photo via NewspaperSG. Click image to read article

And when roof area was burnt or damaged, as it turned out, a private landowner would lose the land the damaged roof covered to the government — a old clause from the 1960s under the Land Acquisition Act, mentioned by the late Lee Kuan Yew in a parliamentary speech on a reading of a bill, that is little-known because it so rarely happens to anyone.

A subsequent reproduction of a 2007 Straits Times article appears to show that this clause has since been removed from the Act, previously imposed to penalise landowners who burnt property to get rid of tenants.

Grassroots leaders at that point helped by submitting an appeal for the temple to retain and redevelop its original area, but according to Chong, regulations at that time meant that the redeveloped temple's space was reduced — which explains the alley behind.

Chong tells us his parents then worked hard to raise the money to rebuild the temple — after realising there weren't any government-recognised Taoist associations that could lend support, they decided to morph the original temple into a Buddhist one.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

The house next door, which was part of the temple since it was acquired in 1957, retained a smaller Taoist altar, hence making it what it is today — both a Taoist and a Buddhist temple.

The Taoist altar that remains in the extension of the temple. (Photo by Jeanette Tan)

The Taoist altar that remains in the extension of the temple. (Photo by Jeanette Tan)

It's quite quiet on most regular days, Chong says, receiving just a few visitors who stop by to pray or seek answers to questions through 求签 (qiú qiān, or fortune telling in Chinese), or the occasional curious tourist.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

This is arguably a reflection of how things have changed in Geylang in recent years — since it was demarcated as a liquor control zone in 2015 alongside Little India, and saw an escalation of law enforcement presence and raids.

Indeed, says Chong, Geylang (even at night) has mellowed greatly, save for "occasional fights at the bar next door".

A heritage of adopted chaste grandmothers... and one rebellious girl, his mom

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Clad in a loose T-shirt and equally-loose blue pants, Chong welcomes us into the temple grounds, where we also walk barefoot, like he's right at home — and that's because he is.

And he knows so much about this temple because he's lived here for 24 of the 30 years of his life.

How this came to be is a fascinating story too — the original owner of the plot of land was a Chinese merchant who built a holiday villa, but when he discerned he wasn't going to be returning to Singapore he bequeathed it to a niece of his, who became a Taoist nun when she grew up.

Taoist nuns, Chong explains, are chaste and remain single all their lives, working in the temple, and the merchant's niece went on to adopt young girls whose families couldn't keep them and raised them as nuns too — hence kicking off an unusual matriarchal tradition there (temples are usually owned and/or run by men). Chong's great-grandmother, grandmother and mother were all adopted in turn through the generations.

This is Chong's grandma, one of a number of generational matriarchs who handed down management of the temple to eventually his mother, who was also adopted. (Photo by Zheng Zhangxin)

This is Chong's grandma, one of a number of generational matriarchs who handed down management of the temple to eventually his mother, who was also adopted. (Photo by Zheng Zhangxin)

Now of course, his great-grandma and grandma were not his real grandmothers because they never got married or had children until his mother came along.

Chong's mother had a rebellious streak, and like a Singaporean Romeo-and-Juliet story, met a man who volunteered at another temple — much to the outrage of their elders working and volunteering at both temples, they got close, went out, romanced and got married.

After the fire, however, his parents found themselves abandoned with the temple by his mother's adoptive sisters and other people helping out and working there, and that's how his family moved in from their original flat in Tampines when he was six years old, and they lived there ever since.

Of course, as neither Chong nor his mum have been ordained as monks, the temple runs with the aid of a resident monk who carries out the main rituals and ceremonies.

The Chong family serves as facilitators, aiding the monk in accordance with Buddhist traditions.

Rebelling against the temple life, even considering converting to Christianity

You'd imagine Chong to have been a fully devoted temple worker from a tender age, since Taoism (and later Buddhism) is all he knew for the majority of his life, but it was quite the contrary.

"When I said I lived here all my life, I actually rebelled against it," Chong quips cheekily.

And if you think about it, living in a Buddhist temple is no walk in the park for a child growing up in food haven Singapore.

Besides having to help his parents with saikang (menial tasks) at temple events he simply couldn't (and he admits, wasn't really bothered to) understand, his diet was extremely restricted — meals in the temple were always strictly vegetarian (in some cases, plain rice with soya sauce), meaning no eggs, onion or garlic either, not just meat.

Going to Geylang Methodist Secondary School only worsened his disdain for life in the temple, even at various points contemplating converting to Christianity — after all, the fun praise & worship songs, air-conditioned rooms and even the simple fact that they could eat meat anytime made him green with envy.

"Imagine this huge gap between two religions, between two major religions in Singapore. I sort of almost became Christian after I thought how fun they were... it's a bit of a bummer and therefore during then I was like, 'Why was I born here?'"

Growing older, & rediscovering meaning

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

University changed all that, though.

In 2015, when he was working on his final-year project in his Master's in Fine Arts degree course at Nanyang Technological University, he realised he should take a step back to re-examine his roots, and to rediscover the faith that brought him to where he was.

His research into fengshui, his chosen topic, made him discover connections to and a newfound appreciation for elements of his mum's divination practices for the temple's devotees.

Seeing it as a signal to reconnect with his roots, after some time doing graphic design work for a studio after graduating, Chong now devotes himself fully to work in the temple.

He's also a (recently) happily married man — his wife, whom he met in NTU in his second year, was actually a Christian before her whole family became free-thinkers.

Furthermore, her family spoke mostly English, so you can imagine how different they were in terms of background.

"Her parents was a bit sceptical [about me], because her family was English-speaking, and my family is Chinese-speaking, so obviously there's a communication problem that was bound to happen."

Chong shares with amusement that she was suspicious of him when he told her he lives in a temple (in Geylang, to boot), but of course, would come to learn that he wasn't lying — why would anyone want to lie about living in a temple, right?

And eventually, much like the story of Chong's parents, love conquers all obstacles. His wife, he says, has been supportive and accepting, and recently moved into the temple to live with him too — even if she doesn't actively assist him in his work there.

He adds that she's even started to learn Mandarin properly for him despite having skipped junior college just to avoid it.

That, we have to say, is true love.

Praying for the spirits of aborted and miscarried children

Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

Now as someone who lives and works in a temple in Geylang, Chong has seen his fair share of interesting things and people — fights, gambling dens and sex workers were part and parcel of daily life for him.

And naturally, the temple's unique location also makes it a place of prayer for vice workers — in particular prostitutes who come by to pray for the babies they abort or lose when they accidentally conceive.

These ladies would buy "a space" in the temple for the miscarried or aborted child, and present prayers to appease the child, as well as offerings such as filled milk bottles.

He relates a story he learned from the resident monks and older volunteers: there was one particular prostitute who came into the temple many years ago behaving like a child.

She wouldn't eat anything except for sweets like chocolates. A temple medium then determined that she was possessed by the spirit of her aborted child, whom she had failed to pray for.

Over the years, Chong has noticed strange occurrences with his own eyes too, such as milk within milk bottle offerings separating out into two layers within a day, with the milk-coloured liquid floating above the clear liquid.

Notice the separation of milk sediments and clear liquid in the bottle. Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

Notice the separation of milk sediments and clear liquid in the bottle. Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

He'd also see the tit of a few bottles compressed or dented as if a child had sucked on it.

Taking the temple into the next generation — and dragging his reluctant mother along

Other than learning how to carry out the necessary rituals, and strengthening his own faith over the years, Chong now plays a vital role in modernising processes within the temple.

One instance of this is the ancestral slip, designed for writing the names of ancestors and details such as dates, which he used his graphic design skills to improve.

The original template used (the smaller slip of paper below) has a narrow space, which made writing details on it challenging especially as Chong's parents grow older and their eyesight poorer.

Chong made a much bigger sheet design, which allows more space to write, along with a modern, simplified design that still borrows inspiration from the graphics of the original slip.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

For Seventh month preparations, he also assisted with a transition from bulky paper ancestral tablets used during the month of the Hungry Ghosts Festival into slips stored within reusable aluminium frames.

Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

Photo courtesy of Alan Chong

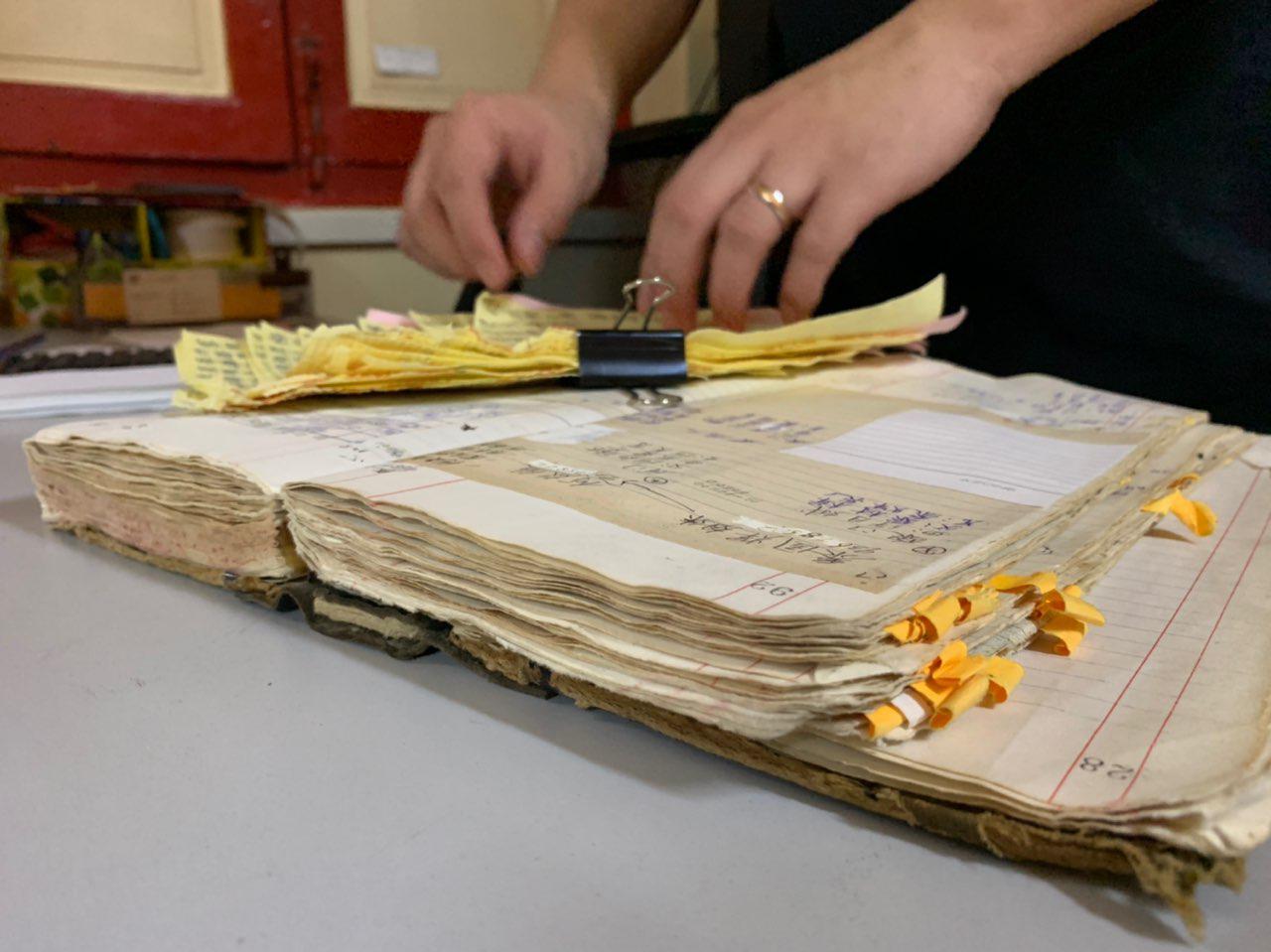

Right now, he's working toward transitioning to a proper digital database of temple devotees — an endeavour that he has found a certain extent of success in so far.

Previously, his mother would record information on paper without much organisation, in accordance to each occasion that happened within the temple, and in books that are now rotting with age.

Chong has helped her to kickstart the process of logging the names of the dead and their next-of-kin in a proper database, with numbers, addresses, family members alive as of now and family members dead as of now for the temple to pray for and to.

Photo by Jeanette Tan

Photo by Jeanette Tan

He readily shares with us that this process, even if it is supposed to help his mum work better, has not been easy. Clashes are inevitable, and he says she is far from ready to hand over the overall organisation and running of operations at the temple to him.

"I'm trying to improve the way she's working [and] her work processes. Sometimes I'll get into a fight with my mum — 'why you always like that, so messy, I can't take it!'

I think she's holding even tighter now... I mean, it's hard to let something go when you have built it up your entire life. It's totally understandable. And that's why [for now] I'm only on the side as an auxiliary support to improve her workflow."

But that being said, Chong is perfectly okay with her stance. As it stands now, he has managed to reach "an equilibrium" where his mum, perhaps in recognition that she isn't getting any younger, does entrust some of the work to him, and he feels it's good for him to take on tasks incrementally as he gets more involved too.

Altruism, a thread that binds all religions

Christmas tree decorations added to the altar over the year-end period. (Photo via Chong Tuck Tong Temple Facebook group, by Alan Chong)

Christmas tree decorations added to the altar over the year-end period. (Photo via Chong Tuck Tong Temple Facebook group, by Alan Chong)

In Chong's own reflections, he sees an increasing difficulty in teaching others about Buddhism or Taoism as people are "becoming more secular" or interested in new-age practices, though he feels there is still a good deal of common ground.

A lot of religions, he says, advocate being altruistic, and build a bond between people, albeit in different forms and with varying levels of faith and spirituality required.

He mentions "Pass It On", a praise and worship song he remembers singing in his Geylang Methodist days, which to him symbolises the metaphor of lighting a candle for others — which he compares to lighting a candle in the temple when someone makes a donation.

He also hopes to be one of a generation of young people who forge connections between our parents' generation and the next, understanding traditions of older religions and incorporating their meaning and significance into new practices, in his own little ways.

For many of us who barely go to temples, people like Chong form the connection between past and present, showing that even an old temple can still be relevant, applicable and modernised — all while bringing a more humane light to Geylang.

Top photo by Jeanette Tan

Content that keeps Mothership.sg going

??

Property hunting can be a chore, but we made it into a game. Sort of.

???

Pretty pastries and cheese fruit teas. Instagram-worthy cafe without breaking the bank.

??

Earn some CASHBACK right now! Don't say we never jio.

?

Find out which decade you should be born in.

??

Here's how to pair your CNY snacks with beer to look like a true blue connoisseur.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.