This is a continuation of the Secrets of the early triads in Singapore: Part 1

The Riotous 1850s

It was more than a decade ago since you arrived as a sin kheh (new immigrant) from Fujian and met Ah Kow. The mid 1850s threw the secret societies into the public spotlight as turf wars and economic discontent prompted them to resort to violence.

Anti-Catholics riot (1851)

February 1851. The past 5 days have been a bloody mess.

For quite awhile now, many secret society members have been converting to Catholicism, resulting in a greatly reduced membership in the kongsis.

The hardest hit was the Ghee Hin Hoe (义兴会). Their leaders were furious. Additionally, there were rumours that the Catholic plantation owners were smuggling opium into their plantations – a direct threat to the opium businesses operated by secret societies.

The discontent resulted in a 5-day massacre that killed 500 and saw 28 pepper and gambier plantations razed to the ground

In the end, thanks to mediation, both parties agreed on a settlement amount of $1,500 and some rioters were jailed.

Pepper plantation in 1890s

Pepper plantation in 1890s

Hokkien-Teochew Riots (1854)

As the immigrant population continued to swell, the different dialect groups (especially the Hokkiens and the Teochews) in your kongsi began to splinter into different factions. Tension rose between both groups as each saw the other as a direct economic threat, especially over the control of pepper and gambier plantations.

May 1854. You were having your lunch on the street when suddenly an outburst across the street caught your attention. A Teochew coolie was arguing with a Hokkien rice merchant over the price of several katis (斤) of rice.

Bystanders began to take the sides of their dialect compatriots and without warning, the mini shouting incident escalated into physical blows.

You did not notice someone coming up behind you with a knife in hand.

Over the next 10 days, about 500 people were killed and 300 homes destroyed.

The Road To A Split Head Is Paved With Good Intentions

As secret societies gained infamy with their riots and unrest, William Pickering, with his knowledge of Chinese customs and language, was appointed the Chinese Protector in 1877. Essentially, Pickering was a bridge between the British government and the Chinese immigrant community. His good relationship with the Chinese meant that their problems were brought to the government, thus avoiding the bloodbaths that occured when secret societies handled matters.

William Pickering, Protector of the Chinese

William Pickering, Protector of the Chinese

Additionally, Pickering’s job scope included protecting new coolies from becoming coolie trafficking victims, as well as freeing prostitutes from brothels. While that was all good, his actions inevitably angered the secret societies who saw his good intentions as interference in their money-making businesses.

In 1887, a purported triad member attempted to kill Pickering by flinging an axe to his head. The assassination attempt was unsuccessful but it forced him into early retirement in 1888.

A fight to bring down secret societies

The violent nature of secret societies in the 1800s alarmed the British government. In a bid to control them, the government enacted several acts which slowly but surely dealt fatal blows to secret societies.

The Peace Preservation Act (1867) gave the colonial government the power to detain and deport convicted Chinese immigrants. The fear of deportation was a major tool in slashing society membership.

The Ordinance for the Suppression of Dangerous Societies (1869) made it compulsory for all societies with more than 10 members to be registered with the Police Commissioner, allowing the government to keep a close eye on them.

In 1890, the Societies Ordinance was enacted, outlawing all societies that engage in triad rituals, hence forcing secret societies underground. Some disbanded in the process while others evolved at the turn of the century to become present day street gangs.

New century with old problems

It is 1940. You’re a Chinese immigrant from Fujian, China and it has been a month since you arrived at Nanyang (or Singapore as the people here call it). So far, the reality of Singapore The Tropical Paradise has taken a huge dump on your expectations.

The work is crazy hard, there isn’t enough to eat, and you live in a room the size of a coffin with 10 other guys. To give you strength, you boil leftover pork bones in a broth and season it with pepper. Your room mates love the dish but you wonder who would ever pay for water flavoured with leftover bones.

Thankfully, you met an old neighbour, Ah Huat, who inducted you into his association. Life is a tiny bit better being in an association. The monthly membership fee of 40 cents is a little steep but at least you’re not kidnapped, mutilated or drowned.

In return for the welfare afforded by the association, you have been working hard for them. Recently, you’ve been informed that the Headman (大哥) is pleased with your work and a promotion is possibly on the way.

Of Vice & Men

To celebrate, Ah Huat decides to take you out for a surprise. He leads you out into the bustling streets of Gu Jia Zui (牛车水 – Chinatown) and turn round the corner into an alley before stopping in front of a house with dark red doors.

The sweet, pungent smell hits you in the face as the Ah Huat pushes the door open.

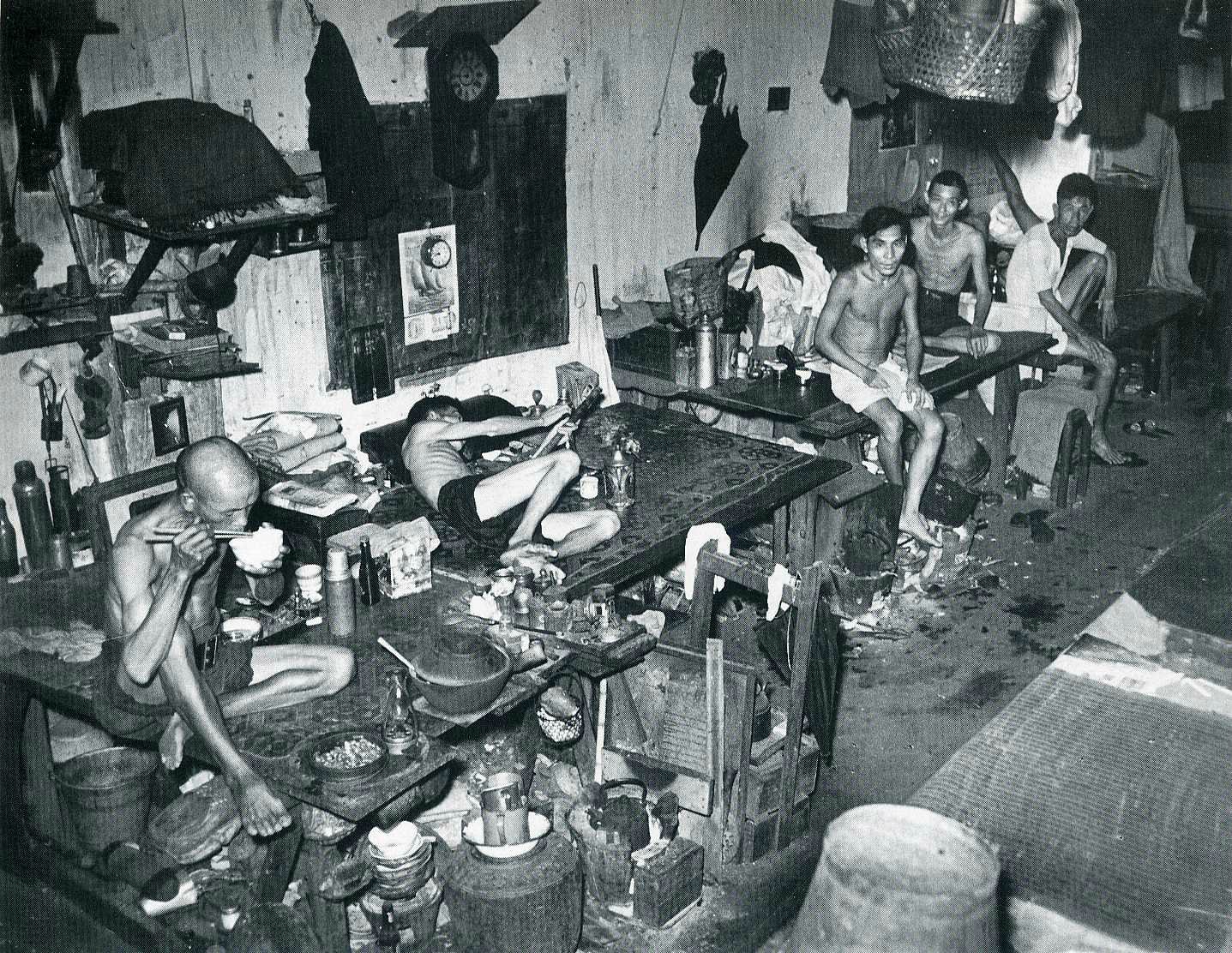

“Opium?” you ask, a little disconcerted at the sight of several dazed men sprawled on wooden benches, bamboo pipes lolling about in their hands.

Southeast Asian Opium Den

Southeast Asian Opium Den

You learn from Ah Huat that the colonial government has once again awarded your association a license for opium processing and selling.

Opium is a very lucrative business and the British administration wants a slice of the opium pie. They monopolise the sale of raw opium by importing and selling it to the highest bidding licensees.

In turn, the licensees process it into chandu (cooked opium) and sell it in their opium dens. Businesses or associations who cannot afford the expensive opium license often resort to buying smuggled opium, which is then processed and sold at a much cheaper price.

The practice of licensing opium would continue up to 1943 when the government banned it. Even then, popular opium dens existed up to the 1970s in areas such as Tanjong Pagar, Sungei Road, Beach Road and Amoy Street.

20th century opium den in Singapore

20th century opium den in Singapore

“Come! my treat!” Ah Huat grins as he hands you a pipe. You glance at the listless men in their stupor, then back at Ah Huat’s eager face.

OK. Here goes. The first puff fills your mouth with acrid sweet smoke. You mutter a little prayer as your surroundings fade into a haze ... and for the days thereafter as well.

The other businesses of the triads

19th century gambling den in Singapore

19th century gambling den in Singapore

The colonial government also awarded licenses for the operation of gambling dens in the early 19th century. However, in 1829, the Grand Jury prohibited all forms of gambling, therefore forcing gambling dens underground. Many of the gambling dens operated by secret societies were located at present day China Street which was nicknamed 赌间口 (gambling den opening).

Secret societies invested in brothels, gambling dens and opium dens because they were very lucrative sources of income that catered to the mainly young and single male immigrants.

On a darker note, these highly addictive activities kept the members of secret societies captive to their associations, ensuring the kongsi has a constant source of manpower.

Secret societies and the evolution of worker unions

The earliest forms of labour unions in Singapore were actually secret societies and clan associations. This is why older unions in Singapore have a more “Chinese” flavour to them. Many unions descended from the secret societies/village associations that were set up here when migrant labourers first came to Singapore.

Before Singapore gained independence, many of Chinese migrants were looking to one day return home to China richer. Their unions were “educated” by the norms and developments in China, which at that time was in the midst of a civil war between the KMT and the communists.

To these unions, the KMT was seen as "evil manifestations of debauchery". The unions aligned themselves to the communists who possessed very similar structure, processes and mission to the unions. So many of the earlier unions had a communist zest in them for this reason.

The unions congregated under the Singapore Trades Union Congress (STUC) up until 1961, where STUC got split into the PAP-backed National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) and the Barisan Socialis-backed Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU).

SATU collapsed in 1963 when its leaders were detained by Operation Coldstore (an operation where left-wing activists were detained). SATU was de-registered in 1963 and NTUC became Singapore's de facto union centre thereafter.

The rest as they say, is history.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.