Why are Singapore’s electoral boundaries not intuitive?

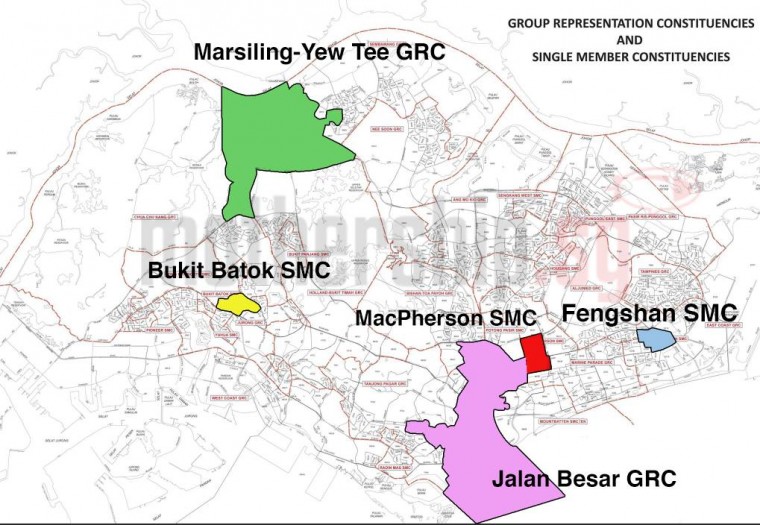

Over the past fifty years, Singapore’s electoral boundaries have been chopped and changed regularly before elections.

This is partly the result of regular, necessary redistricting—and alleged gerrymandering—but also a symptom of major ideological shifts in electoral politics, including the 1988 introduction of Group Representation Constituencies (GRCs) and the more recent push for more single-member constituencies (SMCs) and smaller GRCs.

Check out these trivia questions on which GRC some landmarks belong to:

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Question 4

Question 5

Question 6

Question 7

Question 8

Question 9

Question 10

(Scroll to the bottom for the right answers)

What is the rationale for redistricting?

The basic rationale for redistricting is to ensure “proportionality”: each parliamentarian representing a somewhat equal number of voters. Electoral boundaries therefore have to be periodically reassessed and possibly redrawn to account for population changes. In Singapore, this is the only stated purpose for redistricting.

In other countries, there are potentially other considerations as well: for instance, the need to achieve some desired ethnic mix in districts; the compactness or contiguity of areas; or the need to preserve specific communities of interest.

When does redistricting become gerrymandering?

The word gerrymander has its roots in another inchoate democracy: early 19th century United States. In 1812 then Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry oversaw the redrawing of state senate election districts to the benefit of his Democratic-Republican Party. This redrawing resulted in an electoral map that looked like a salamander. And thus “Gerry-mander” was born.

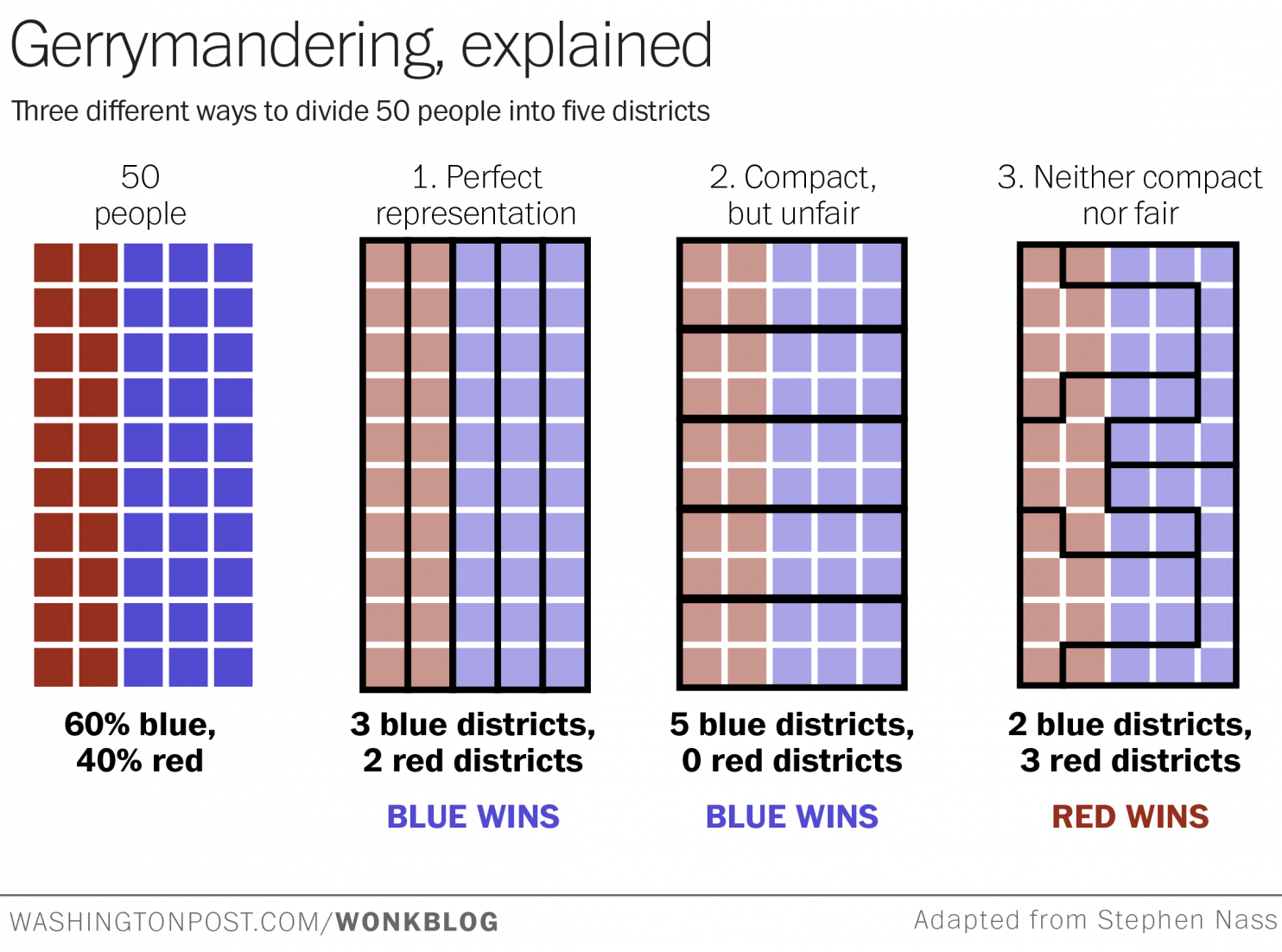

Redistricting is particularly prone to abuse in first-past-the-post voting systems where voting records or political preferences are tracked. With that knowledge, a gerrymanderer has the ability to manipulate electoral boundaries in order to further particular political agendas.

Source: The Washington Post

Source: The Washington Post

“Contrary to one popular misconception about the practice, the point of gerrymandering isn't to draw yourself a collection of overwhelmingly safe seats,” writes Christopher Ingraham in the Washington Post, which has published extensively on the topic. “Rather, it's to give your opponents a small number of safe seats, while drawing yourself a larger number of seats that are not quite as safe, but that you can expect to win comfortably.”

Perhaps every incumbent in every democracy in the world has faced accusations of gerrymandering. Many countries and constituent states are still trying to strike the right balance between incumbent rights and the need for independent oversight.

How do democracies protect themselves against the risk of gerrymandering?

Traditional checks are provided by assertive media channels—Elbridge Gerry’s salamander was first depicted in a political cartoon.

More recently, some places are taking redistricting powers out of incumbents’ hands. In the US, for instance, four states—Arizona, California, Idaho and Washington—have created independent commissions to oversee electoral redistricting.

But at a larger level, not everybody is convinced that gerrymandering is that big of a problem.

There are three common myths about gerrymandering in the US, according to John Sides, an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, and Eric McGhee, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, writing in Politico.

Myth No. 1: Gerrymandering a district always makes it safe for incumbents.

Myth No. 2: Partisan gerrymanders are ubiquitous.

Myth No. 3: Strangely-shaped districts are bad.

In debunking these myths, Messrs McGhee and Sides cast doubt on the extent of the problem in the US.

Is gerrymandering a problem in Singapore?

Although gerrymandering has been studied extensively in the US, its lessons for Singapore may be limited given the huge differences between the two democracies and respective polities.

But here too, given the non-intuitive evolution of Singapore’s parliamentary districts, frequent gerrymandering accusations are made against the establishment.

The Elections Department in Singapore is not an independent agency, but a department in the Prime Minister’s Office. There are concerns that the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee relies on block-level polling data in its boundary analysis.

Compounding this institutional conflict of interest is a lack of transparency. Before each election, the committee issues a white paper—The Report Of The Electoral Boundaries Review Committee—detailing its redistricting proposal. This is arguably the most threadbare document in the history of government, starved of any explanation behind boundary and district changes, putting all of them down blithely to “population shifts and housing developments”.

In light of the most recent report, Mothership.sg has compiled a table that ranks constituencies in descending order of voters per representative:

| Constituency | Number of voters | Voters per Representative |

| Punggol East SMC | 34,410 | 34,410 |

| Bukit Panjang SMC | 34,299 | 34,299 |

| Ang Mo Kio GRC (6) | 187,652 | 31,275 |

| Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC (6) | 187,252 | 31,209 |

| Sengkang West SMC | 30,097 | 30,097 |

| Chua Chu Kang GRC (4) | 119,848 | 29,962 |

| Aljunied GRC (5) | 148,024 | 29,605 |

| Marine Parade GRC (5) | 146,087 | 29,217 |

| Sembawang GRC (5) | 144,604 | 28,921 |

| Radin Mas SMC | 28,885 | 28,885 |

| Tampines GRC (5) | 143,426 | 28,685 |

| Macpherson SMC | 28,481 | 28,481 |

| Hong Kah North SMC | 28,131 | 28,131 |

| Bukit Batok SMC | 27,068 | 27,068 |

| Marsiling-Yew Tee GRC (4) | 107,527 | 26,882 |

| Nee Soon GRC (5) | 132,200 | 26,440 |

| Tanjong Pagar GRC (5) | 130,601 | 26,120 |

| Holland-Bukit T GRC (4) | 104,397 | 26,099 |

| Jurong GRC (5) | 130,428 | 26,086 |

| Bishan Toa Payoh GRC (5) | 129,850 | 25,970 |

| Jalan Besar GRC (4) | 102,454 | 25,614 |

| Pioneer SMC | 25,453 | 25,453 |

| West Coast GRC (4) | 99,236 | 24,809 |

| East Coast GRC (5) | 99,015 | 24,754 |

| Mountbatten SMC | 24,096 | 24,096 |

| Hougang SMC | 24,064 | 24,064 |

| Fengshan SMC | 23,404 | 23,404 |

| Yuhua SMC | 22,599 | 22,599 |

| Potong Pasir SMC | 17,389 | 17,389 |

Here are just three issues that stump us. Thorough explanations by the Elections Department would go some way toward fending off gerrymandering accusations.

1. Why is Potong Pasir so small?

Potong Pasir SMC, the constituency at the bottom of this ranking, has just half the number of voters as Punggol East SMC, the one at the top.

Why, over all these years, has the boundary of Potong Pasir, opposition controlled from 1984 till 2011, not been enlarged?

The most obvious district from which to carve off territory is Marine Parade GRC. As per earlier photograph, it seems odd that Lorong Chuan and a good chunk of the Macpherson/Aljunied area, which are many kilometres away from the nearest coastline, are part of Marine Parade rather than Potong Pasir.

Incidentally, the recent white paper (The Report Of The Electoral Boundaries Review Committee, 2015), states that the voter range for single-member constituencies is 20,000-37,000. Potong Pasir has only 17,389.

2) Why is Holland Village a part of Tanjong Pagar?

Ahead of the 2011 elections, the Elections Department decided to slice off Holland Village from its own eponymous district, Holland-Bukit Timah GRC. It is a wonder the department didn’t just rename the constituency as Bukit Timah.

There was no “proportionality” justification here. Tanjong Pagar GRC, with 27,954 voters per candidate, had one of the largest voter bases. Holland-Bukit Timah GRC, with 22,901, one of the smallest. If anything, a few Tanjong Pagarans should have been pushed out. (Note: These are elector numbers at the 2011 election.)

All things considered, this is the main gerrymandering conspiracy theory: with the late Lee Kuan Yew at its helm, Tanjong Pagar had always been the PAP’s safest bet. Holland-Bukit Timah, by contrast, was looking particularly risky given that its team leader, Vivian Balakrishnan, had publicly born the brunt of the blame for the Youth Olympic Games fiasco in 2010—when the government exceeded its budget by more than three times.

Therefore, in order to bolster the Holland-Bukit Timah team’s chances of re-election, the Elections Department moved Holland Village—and all its artsy, counter-cultural, presumably non-establishment inhabitants—to Tanjong Pagar.

That is, to reiterate, the main conspiracy theory.

3) Why has Moulmein-Kallang just been dissolved?

While gerrymandering is universally practised, Singapore may have perfected the art of constituency obliteration. Remarkably, the Moulmein-Kallang GRC was around for only one electoral cycle: formed before GE2011, dissolved in 2015.

Why? Again, there seems no logical explanation grounded in electoral dynamics. Instead, the main conspiracy theory is that the Elections Department got rid of the district in order to smoothen the retirement from politics of Lui Tuck Yew, the PAP team’s leader and under-fire transport minister.

If true, this is an astonishing feat. It would mean that not only is the Elections Department prone to gerrymandering, but it sees itself as a facilitator of PAP leadership transitions. It is a worrying instance of mission creep.

(The recent boundaries white paper was published on July 24th 2015. Lui Tuck Yew resigned on August 11th 2015, although he had first informed the prime minister of his intention to leave in early 2015.)

Summary

Without more granular data on voter patterns, it is impossible to assess the significance of any possible gerrymandering on electoral outcomes in Singapore. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to expect that Singaporean voters, like their counterparts in other developed democracies, will clamour for greater independence and transparency in the redistricting process.

Note: Mothership.sg attempted to contact the Elections Department four times for an interview in order to clarify many of these issues of importance to Singaporeans. The Elections Department responded after eight days of our initial request. Unfortunately, our editorial deadline for this piece had by then passed. Nevertheless, we have sent the department our questions, and will publish their responses here if and when we receive them.

Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh is the author of Floating on a Malayan Breeze and co-author of Hard Choices: Challenging the Singapore Consensus. He blogs at sudhirtv.com. He sits on the board of Mothership.sg.

Answers:

Q1: Ang Mo Kio GRC

Q2: Marine Parade GRC

Q3: Marine Parade GRC

Q4: Bukit Batok SMC

Q5: Holland-Bukit Timah GRC

Q6: Tanjong Pagar GRC

Q7: Jurong GRC

Q8: West Coast GRC

Q9: Jalan Besar GRC

Q10: Nee Soon GRC

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.