All of the following things about Singaporean hotel tycoon Ho Kwon Ping are true:

1. He was jailed twice — once in California and once in Singapore;

2. He was a fiery journalist with a now-defunct publication that was renowned for its hard-hitting pieces on corporate and financial scandal, business and politics;

3. He was at one point so poor he lived for three years with his wife Claire Chiang (now a very successful career woman in her own right) in a fishing village on an island off Hong Kong;

4. He and Chiang founded the luxurious and successful Banyan Tree Hotels & Resorts group of businesses (which you might not have heard of because you don't have enough money to stay there) while living in a two-room rental flat; and

5. He helped start up the Singapore Management University (SMU).

With all these experiences beneath his belt, it's interesting that Ho, now 63 (the same age as Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, by the way), not only continues to run a multimillion-dollar hotel group, but also sits on numerous government boards like (previously) that of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC), while also chairing the board of trustees at SMU.

Photo courtesy of the Institute of Policy Studies

Photo courtesy of the Institute of Policy Studies

And the latest item added to this lengthy list: his completion of a stint as the first S R Nathan Fellow for the Study of Singapore. During his stint, Ho conducted five gruelling lectures (the IPS-Nathan Lectures) on all kinds of hard questions that keep Singapore's political leaders awake at night.

So how does one manage to cooperate with the government, while at the same time voicing the renegade-sounding opinions about governance in Singapore that he is known for? And actually, what's a successful businessman doing talking so frequently and so publicly about politics?

He did have answers to these questions, but we think delving into his past may also shed some light.

Born and raised in Hong Kong and Thailand

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

Despite his years spent in considerable poverty, Ho was born into a well-off family. His father, Ho Rih Hwa, apart from being a former Ambassador to Thailand, also for a time ran the family business — a manufacturing company. And his mother: well-respected bilingual writer and chemist Li Lienfung.

Thanks to his father's diplomatic appointments, Ho and his siblings (one of whom was his younger sister Ho Minfong — Sing to the Dawn, anyone?) spent some of their earliest years growing up in Thailand. That period, the 1960s, saw the Vietnam war in full swing, and these experiences (if you haven't heard of Agent Orange) did not go ignored.

His time in school, and behind bars

Ho went to Taiwan for his university studies — after a year at Tunghai, he spent three years at Stanford, where his protesting against the U.S.'s involvement in the Vietnam War landed him a night's stay in California jail with "lots of other people, drunks and others".

Well, not exactly — the official reason he was in the lock-up overnight was apparently burglary: Ho was accused of stealing the book Madame Bovary from the Stanford bookshop. That, said campus police, made him a felon, and so he had to appear before a judge, who wouldn't be available till the next day.

"I was supposed to be a Marxist, right?... (Yet the book was) about a super bourgeois woman, so it's totally ironical," he said. But he knew campus police wanted him for what we would today call his 'shit-stirring' activism, and so found the perfect excuse in this accusation, which he maintains wasn't even true.

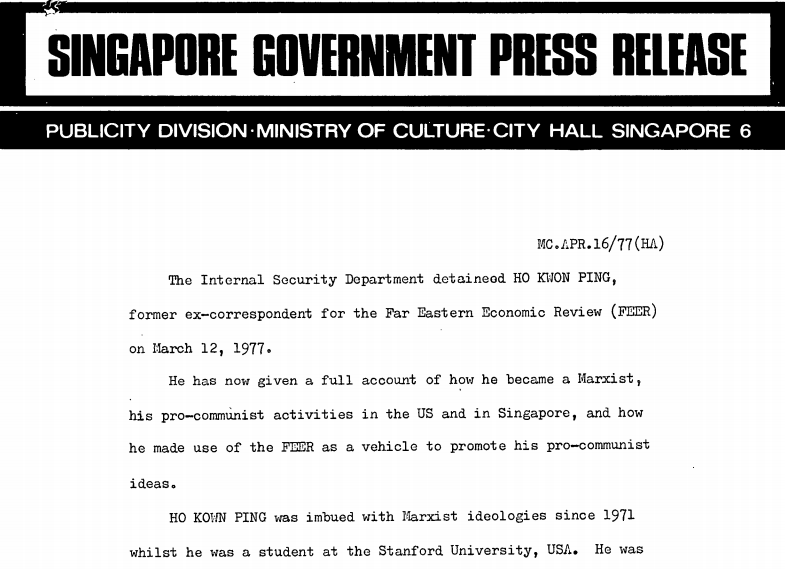

Needless to say, the next day, the judge threw out his case, even declaring it "stupid". But all this, Ho says, was "no big deal" after getting arrested under Singapore's Internal Security Act (ISA), while writing for the Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER).

Click image for full statement

Click image for full statement

Detention in Singapore, for Ho, was a solitary affair — taken in at age 24, Ho spent two months in a windowless room with the lights permanently on, not knowing night from day, when mealtimes were supposed to be, or if he was feeling hungry at the right times.

"And I remember breaking into cold sweats because you have no sensation of time. You just... you try to be in an environment with absolutely no stimuli, and your mind starts to roam, and you start to think about different things. And you know how when you're waiting for somebody even? Half an hour you look at your watch, one hour you look at your watch, two hours you look at your watch — imagine that going on endlessly, and you're going crazy. There's no watch, there's no book, there's no stimulus, there's no sensation of time. You sometimes are given a meal when you think you're not hungry at all, and sometimes you're given a meal when you're starving, so you're totally disoriented."

Ho saw no one for almost a month, until he did a televised confession, which he only got to watch about 30 years later upon (and chiefly because of) his appointment as chairman of MediaCorp. After that, his parents were permitted to see him "once every I don't remember how long".

This experience inspired his proposal to Chiang, saying to her in a movie theatre, "You know, if I'm going to be arrested again, I don't want to be not allowed to see you. So why don't we get married?"

Thankfully for him, she agreed, albeit retorting sharply, "You should never get arrested again!" And off they went to Hong Kong, after he went to NUS to complete one more year of his very-long-drawn-out Economics degree studies.

Living in a fishing village

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Wikipedia

As if he hadn't gotten himself into enough trouble already, Ho rejoined the FEER — this time, in Hong Kong. His three-year stint was spent shuttling in and out of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon from a fishing village in a place called Lamma Island — also known as the only place near enough to his office where he could afford to live.

"They're all three-storey buildings out in the farms and fishing villages, pretty much the standard size. And normally the owner will stay on the ground floor and rent out two floors. The wealthier tenant will have the top floor with the sundeck, and the lower one will be in the middle. And all the journalists will take the middle ones because the only other non-islanders that would be staying on Lamma would be hairdressers from Vidal Sassoon. And they made more money than journalists. I was quite irritated."

That said, Ho says his time there with Chiang were "the most idyllic years of our lives before we had children". The northern village where they lived was called Yung Shue Wan, which means "Banyan Tree Bay" — and that's where the name of his hotel group came from.

From there, he and Chiang moved back to Singapore to take over the family business, after his father suffered a stroke. His years of work and success with the Banyan Tree group now places him in "a very nice house on a very big piece of land", but he attributes his handsome property to "luck" more than his own effort, oddly.

"I think if we didn't have either the luck of taking Banyan Tree public, or the luck of my father owning a piece of land which he bought in 1969 after the riots in Malaysia when Singapore's land prices just plummeted... if not for that I would probably be staying in a semi-D (semi-detached) or terrace (house) right now. Because property prices now are so ridiculous. How could you ever hope to live in a bungalow in Singapore?"

Working with the government

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

How did Ho go from journalist to jailbird to islander to businessman, and then go on to work with the Singapore government on so many things?

Bar labelling him a sell-out, it wouldn't be a stretch to think he has mellowed out significantly over the years.

After all, one would expect that being wrongfully detained without opportunity for trial, denied the right to see one's loved ones and then having to do a televised confession for something he didn't even agree with, would leave a person bitter at best, vengeful at worst.

Yet, Ho went on to chair Singapore Power, and apart from starting up SMU, also served on the board of the GIC, the Civil Service College, MediaCorp, Singapore Airlines and the Singapore Tourism Board, among a host of other organisations.

He, too, admits he is an anomaly among people who were arrested under the ISA — after all, how many former detainees do you see working so prominently and openly in Singapore?

His views on Lee Kuan Yew

Ho also maintains his position that he was arrested wrongfully, but here's what he has to say about it:

"With all due respect to the government and to (the late) Mr Lee Kuan Yew, who I deeply respect and admire... I do not believe Mr Lee Kuan Yew was correct. I was not a communist, but what I do believe was that he honestly believed that I and other persons that he arrested were a threat to Singapore, for whatever reasons. I do not believe he detained me for his own personal gain, because he was corrupt and I was going to expose him, like 1MDB. He detained me because he thought he had to do it."

Also, consciously or unwittingly, Ho believes the manner in which the late Lee engaged him in the decades that followed sent him a message of reconciliation, in his own indirect, strategic manner:

"In retrospect now I think he... well, he would never admit it, he's not the kind of person that would ever admit it, but the fact that after that he was quite nice to me, the fact that he asked me for dinner, for lunch many times, the fact that we had a lot of discussions, the fact that he asked me to join the board of GIC and all these other things, is a man who's basically said, 'I'm never going to say sorry but look, would you like to help us out?' and so on.

Again, I would do the same thing too. We all have our own face and so on. And I think to his mind, quite frankly, his mind would be 'Why do I have to say I'm sorry? I did what I had to do. And you're not what I thought, so okay, I come back to you now and ask you would you like to serve the country.'

So I only have the utmost respect for him as a person, not necessarily if you look back now that he's dead, but I got to know him much better in the later years. He was never a man who ever did a single thing for himself. He could be really excessive, he could be paranoid, a lot of things, and that's why a lot of young Singaporeans I think realise when he died that he never did anything for himself. And so that's why I bear absolutely no bitterness."

Ho then went all Sigmund Freud with the late founding prime minister:

"Somebody said it quite correctly that Lee Kuan Yew was never corrupt because he was too intellectually arrogant. Corruption was below him. Only lesser mortals would be corrupt. And I think that's partly true. To him, corruption was never a temptation. He never cared about material things. He wanted power, and he had almost absolute power, but lesser mortals would want absolute power to create wealth. He wanted absolute power to create the Singapore that he wanted to create."

Ho also touched on Lee's legacy:

"In terms of his legacy I think to me the main legacy is not about, well of course there's the obvious legacy of creating the country and all that kind of stuff... But what he has left behind is if you look at Southeast Asia and the rest of the world, Singapore is a true exception — is this culture of incorruptibility...

And this is where I kind of think the Western media in some way is somewhat insulting to Singaporeans when they say that we Singaporeans are so stupid, we've tolerated this authoritarian government. I think Singaporeans have made a social contract. They basically have said 'yeah, we know you're authoritarian, we know you're this sort of stuff, but you're doing it for us and we can see you're not corrupt.' I think Singaporeans are very strong-minded, and the minute the PAP is corrupt they'll throw it out. So this culture of incorruptibility is probably his strongest legacy. And he demonstrated it in incredible ways."

The next question I had, then, naturally, was — was Ho ever invited to tea? The answer, to our surprise, was an honest yes.

In the '80s, he said, stressing it was "way back", while cheekily adding he would not be able to sell copies of his memoirs if he told me more, should he ever opt to pen one.

On politics and running for the Presidency

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

Since we were on the topic of politics and entering it, I revisited a question we asked him last year: does standing for the Singapore presidency figure in his future?

His response, once again: Yeah, right. He did initially give me a flat "no" when I suggested politics as something he might want to do next, but went on to say this:

"I think first of all you have to decide that you think you've got something to contribute more than others who have declared an interest in the position... I mean, if you wanted to take it seriously. If right now, nobody is running and then some joker runs and I really thought this person was going to destroy the country and assuming nobody runs, then you might feel that you have to do it."

At this point, he mentions 2011 presidential candidate Tan Cheng Bock, who came in a razor-thin second to President Tony Tan in that year's polls, noting his extensive career in public life and service.

"I'm not saying that nobody else is better, there may be other people, but if he (Tan) becomes president, is it going to ruin the country? No. So there's no compelling need, is my point. The only reason I would run would be out of ego. Right?

If you asked me quite seriously, would I do another book, I can tell you honestly I've been approached to do a collection of my essays; I've been asked whether I would like to write my memoirs — (and in) writing my memoirs, my question would be 'am I that old yet?!' (If we did a) collection of my essays, my question is, would anybody really be bothered to buy??

So you ask those questions, but those are legitimate questions. Asking whether I want to run for president, the question is, what's the compelling need? Do I really think I'm better than everybody else out there? Do I really want to have the glory of representing the country? Why you? Why me? Why you? why him? Why?"

At 63, still too young to think about legacy

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

Photo by Kelly Wong for Mothership.sg

All this leaves us with, then, is what is next for Ho — for him and for Banyan Tree, in the coming 50 years?

Ho feels he's still too young to "think about what you want to leave behind" — after all, he says he's too busy thinking about what he still wants to do: a Lego town the size of the sofa in his office that I was seated on, for instance (he was joking, I hope).

Careful to hold his cards close to his chest, he shares that "essentially everything" he's been doing in his lifetime has been a vehicle to doing something he wanted to do. Banyan Tree, for instance, isn't about owning hotels:

"It's a vehicle for me to do quite a number of the things I wanted to do — about promoting people, about creating a culture where people from local nationalities without much education can rise high, that's a theme I've always wanted to have.

Through education (like his work at SMU), I've wanted to see Singapore students — who no doubt are already more privileged than others, like Malaysian, Thai, or Indonesian, but not as privileged as what you see Western students — I've wanted to see how Singaporean young people can really take the right place in the world. I've wanted to see how Singaporeans who may not be that wealthy or privileged are able to rise within Singapore through education...

My biggest pride now in Banyan Tree is not just in building another hotel, although it's a lot of fun, but it's really creating opportunities for people who would otherwise not normally have had the opportunity to actually realise their potential."

On Banyan Tree, we managed to touch on the topic of two of his three children, whom he says with gladness are "quite keen to be involved in the management" of the business, although he says it isn't something he "can ordain or decide".

"It makes family reunions very productive — family reunions and work meetings are related. But yeah, you sometimes have to say 'stop stop! no more business'."

So, what can we expect from Ho Kwon Ping in the coming years? It's hard to say — his growing up years would have framed a fiercely liberal mind that seeks and strives for justice and the power to enact it; yet, his years running a publicly-listed business will have informed him of the subtleties of operating and thriving in Singapore.

But perhaps all this mystery of who he is and what, precisely, he stands for, is due to him being a victim of his own tendency to say yes to things: setting up a university, sitting on the GIC board, chairing a statutory board and the state broadcaster, for instance, right down to saying yes to conducting five lectures on issues he maintains he is no expert in — all these, possibly, make cynics wonder if he's going out of his way to help for visibility.

All that said, Ho could still surprise us with his next steps, surely. After all, he's too young for us to know, right?

[related_story]

Ho Kwon Ping's book, "The Ocean in a Drop", a compilation of the five lectures he gave under the S R Nathan fellowship, is available here and at all major bookstores in Singapore. Check out our Facebook page (have you liked it yet?) to win a free signed copy!

Related article:

S R Nathan Fellow Ho Kwon Ping says “Yeah, right” to running for elected president

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.