Most of my knowledge of Singapore’s early years comes from my grandfather. His stories helped me imagine an old Singapore that had already disappeared from the urban landscape by the time I was born in the late 1980s.

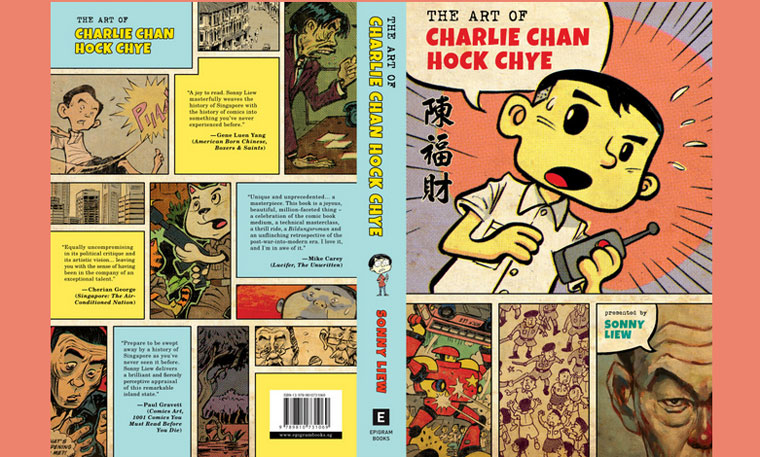

Reading Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye echoed this experience. Like my Peranakan grandfather, the graphic novel’s protagonist – the comics artist Charlie Chan Hock Chye – is a Singaporean Chinese who went to English schools, never learning Mandarin.

From this, the subtleties of language and communication in Singapore’s hodge-podge population thread their way through the entire narrative of Chan’s life and his observations of tumultuous periods like the Chinese students’ protests and Operation Spectrum (depicted as a plot to convert everyone in a stationery company to fans of Richard Marx).

I ordered this book online once I heard of the National Arts Council’s decision to revoke the book's grant. I admit I would probably not have heard of this book otherwise, or given much thought to it even if I had.

Apart from Doraemon and a minor episode in my teenage years where I struggled through Japanese manga translated into traditional Chinese, I have read a grand total of one other graphic novel in my life, of which I remember very little.

[quip float="pqright"] This, my second ever English-language graphic novel, was a revelation not just in the art of visual storytelling, but in the art of telling Singapore’s story. [/quip]

This, my second ever English-language graphic novel, was a revelation not just in the art of visual storytelling, but in the art of telling Singapore’s story.

The narrative is presented as a mix of interviews (supposedly done by writer and artist Sonny Liew) with Charlie Chan Hock Chye and excerpts of Chan’s work, covering Singapore from the post-war years up to the present day. A passionate artist with deep interest in social and political issues, Chan’s commentary on society is channelled through his comic strips. It is mostly through them that the reader gets taken on a journey through modern Singapore’s formative years.

Lee Kuan Yew and Lim Chin Siong appear often throughout the book: as the two heavy-hitters of Singapore’s early political scene, Chan – and by extension, Liew – is fascinated by their manoeuvrings and uneasy relationship.

[quip float="pqleft"] But politicians aren’t the only voices Chan and Liew are interested in: changes in language, landscape and culture are examined through their impact on society at ground level. [/quip]

But politicians aren’t the only voices Chan and Liew are interested in: changes in language, landscape and culture are examined through their impact on society at ground level.

Flipping through the pages gave me a sense of actually travelling through the rapidly-changing city, seeing and feeling the transformation in people’s lifestyles and mindsets. The only other time I felt this journey so strongly and emotionally was when I was reading Balli Kaur Jaswal’s Inheritance.

[quip float="pqright"] Although the book certainly can’t be described as a “neutral” telling of Singapore’s history, Liew generally keeps his own voice out of the story; just like his protagonist, he prefers to let the art speak for him. [/quip]

Although the book certainly can’t be described as a “neutral” telling of Singapore’s history – and I don’t think any piece of art should aspire to that adjective – Liew generally keeps his own voice out of the story; just like his protagonist, he prefers to let the art speak for him. This helps the reader get close to Charlie Chan, a character so recognisable that by the end you feel like you should call him “uncle” and bring him kopi o.

The only time Liew really “breaks character” comes in a small strip bemoaning the insidious ways in which Singapore’s government extended control and influence over the media. Coming after NAC’s withdrawal of its grant, this outburst simply gains new significance.

Liew clearly did plenty of research for this masterful piece of work; there are short notes sprinkled across the pages, as well as more detailed background information provided at the back of the book. Singaporeans with an average grasp of our history and politics probably won’t need these notes. I wonder, though, if this graphic novel will do as well outside of Singapore – I can see someone not familiar with Singapore getting a little lost or annoyed by the need to refer to notes.

Singaporeans don’t often get the chance to really examine the official “swamp to skyscraper, multicultural, fragile-yet-successful, Asian values” Singapore Story.

In most situations – from exhibitions to books and National Day Parades – we’re simply invited to imbibe without question; alternative takes are usually only found in academic articles (too long for the average smartphone obsessed Singaporean’s attention span) and political commentaries (often seen as divisive and strident).

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye is a rare experience to see ourselves in a beautiful piece of work. It’s a chance to think about the stories we tell ourselves, while wondering, “If Richard Marx had written a song entitled The Politburo Only Knows, what would it sound like?”

You can purchase the book online at Epigram Books.

Related articles:

Government authority helps graphic novel “The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye” achieve cult following

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.