There's a museum in London where the official specimen for the cream-coloured giant squirrel is allegedly kept.

One of the largest squirrels in the world, it's found in parts of Malaysia and Indonesia, dwelling in the upper canopies of dense rainforest.

But it was first discovered in Singapore, by none other than Stamford Raffles.

The founder of modern Singapore was passionate about zoology. Upon coming across the strange creature in 1821, he shot it, named it, and shipped it across the Indian Ocean, where it has resided ever since in the dusty drawers of the London Natural History Museum.

Or so it was told. In 2022, a team of researchers from the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum (LKCNHM) flew to London in hopes of searching for this specimen, which has not been seen in Singapore since 1995.

As the original specimen (or holotype, in natural history terms), that squirrel had been the exemplar of the then-newly-discovered species — not to mention collected by Raffles himself in Singapore.

A 14-hour flight and 10,000km later, the LKCNHM team arrived at the museum to photograph this precious piece of local heritage.

But in its place, they found only a common plantain squirrel.

The original specimen was gone.

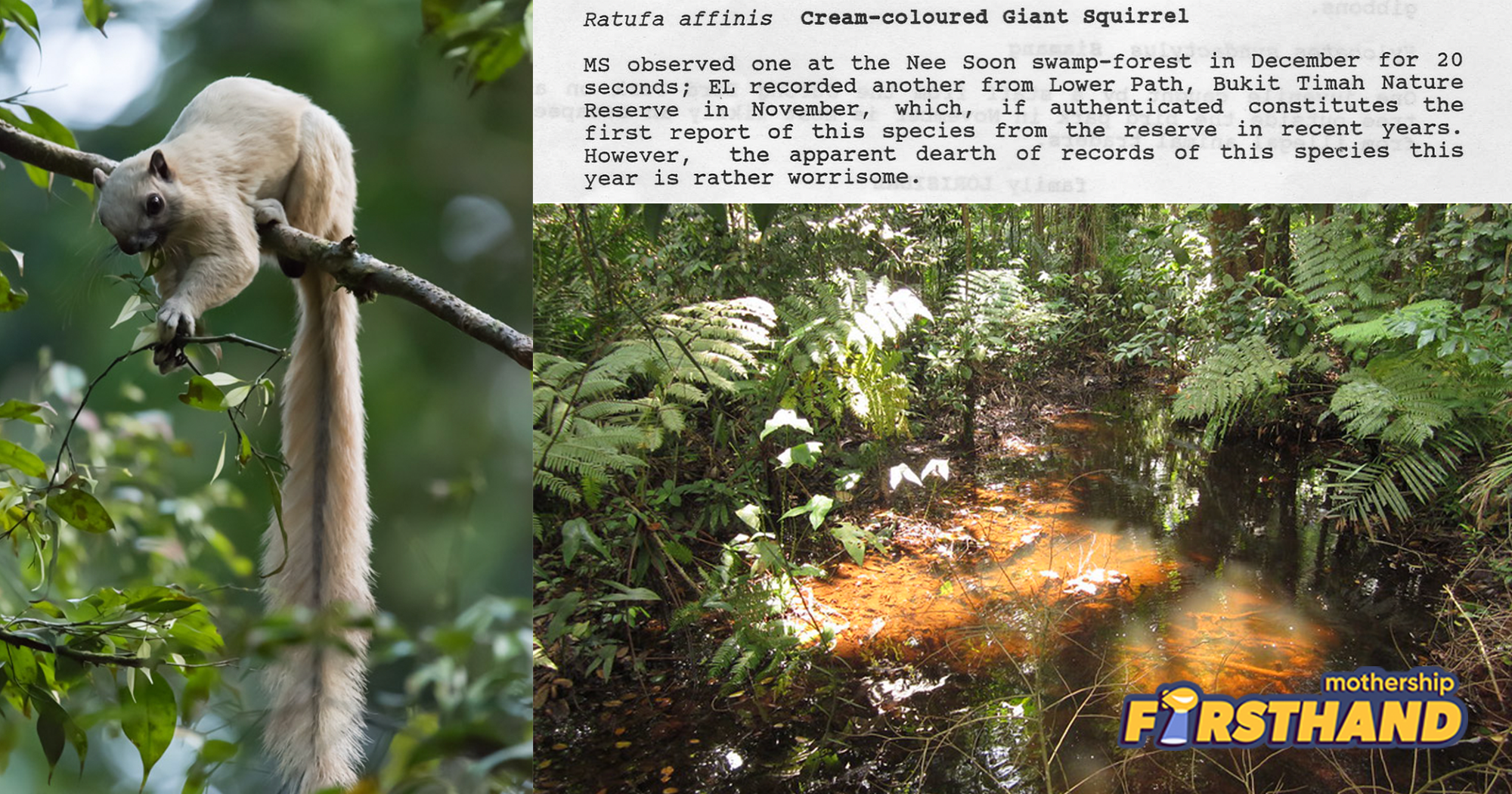

A cream-coloured giant squirrel in Panti Forest, Malaysia. Photo courtesy of Mike Hooper/Viator Photography

A cream-coloured giant squirrel in Panti Forest, Malaysia. Photo courtesy of Mike Hooper/Viator Photography

A plantain squirrel. Photo from NParks' website

A plantain squirrel. Photo from NParks' website

A legendary Pokémon

In Singapore's wildlife-spotting circle, the cream-coloured giant squirrel is a legendary Pokémon of sorts.

Reaching a length of 82cm, it holds the distinction of being one of the largest squirrels in the world.

In Singapore, it is undoubtedly one of the most charismatic squirrels, even once appearing on a stamp.

Photo from Roots.sg

Photo from Roots.sg

The squirrel was once fairly common. It thrived in the lush plantations of colonial Singapore, and Raffles described it as "abundant in the woods". As recently as in the 1960s, people trapped it as game or shot it as a pest.

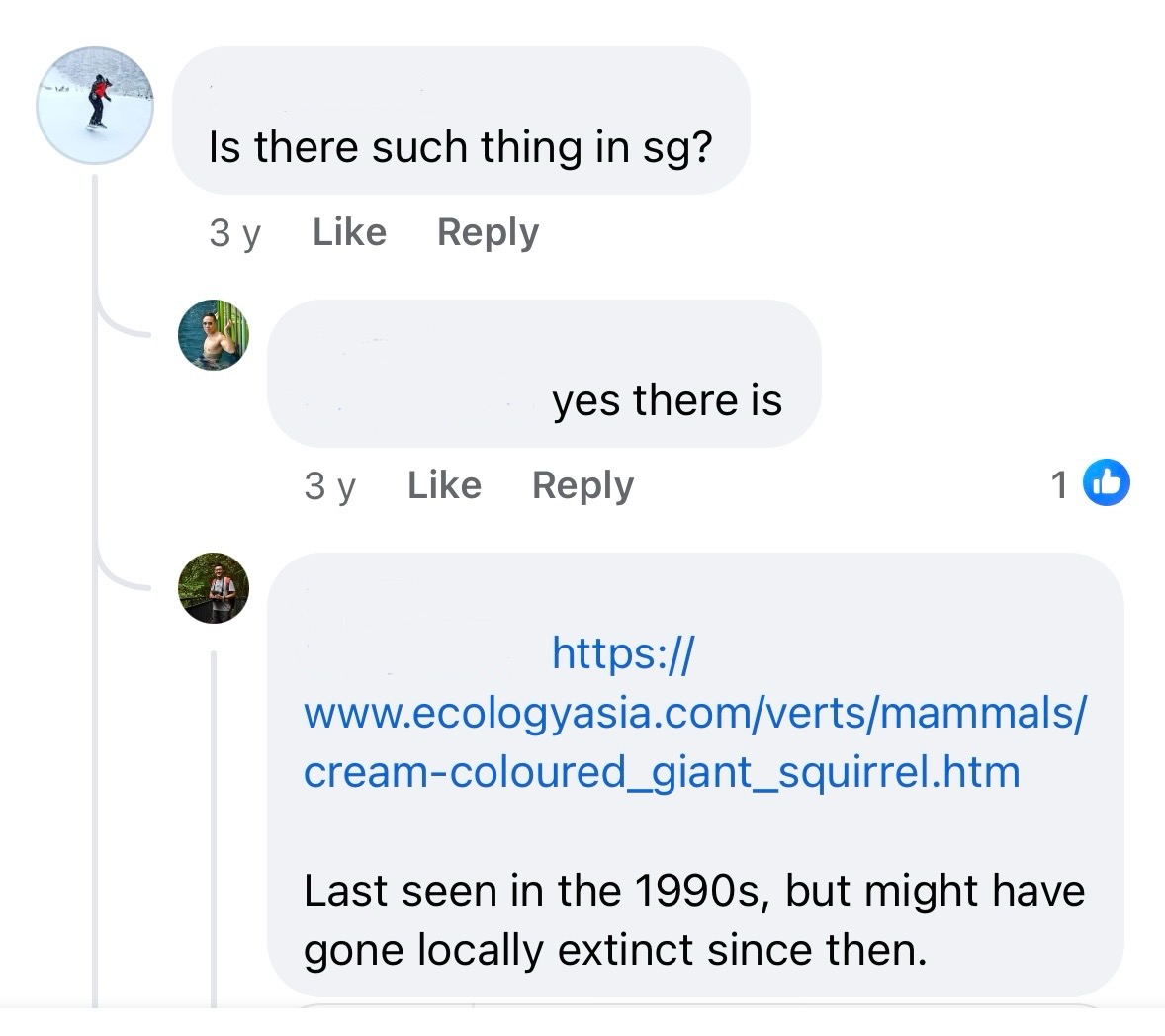

But it hasn't been seen since 1995.

Its disappearance seems to have been breathtakingly sudden. Older nature-lovers have vivid memories of it, while others seem uncertain about whether it's actually extinct.

Image from Singapore Wildlife Sightings/Facebook

Image from Singapore Wildlife Sightings/Facebook

It was only in 2023 that NParks finally pounded the gavel. The squirrel, it declared, was gone — if not as good as.

Still I questioned. Its extinction is contentious; many seemed to regard the squirrel as rare rather than nonexistent.

Besides, hadn't we seen examples of animals who went locally extinct, but made miraculous comebacks — like the smooth-coated otter?

Could the elusive critter still be out there, hiding in the less-accessible parts of Singapore's rainforest?

And if not, could it ever come back?

The search for the squirrel

I'd first heard of the squirrel through Facebook group Singapore Wildlife Sightings.

While a handful of people had reported possible sightings over the years, each glimmer of possibility had been quickly and flatly snuffed out as a case of misidentification.

One was identified as a leucistic plantain squirrel; another, a particularly pale variable squirrel (aka Finlayson's squirrel).

I was left to investigate the only lead I had left: that last sighting, all the way back in 1995.

Not a cream-coloured giant squirrel. Photo from Brandie Li/Facebook

Not a cream-coloured giant squirrel. Photo from Brandie Li/Facebook

After some asking around, I was connected to Yeo Suay Hwee. In addition to chairing the Nature Society’s Vertebrate Study Group, he was also the last person to see the animal.

Or rather, animals.

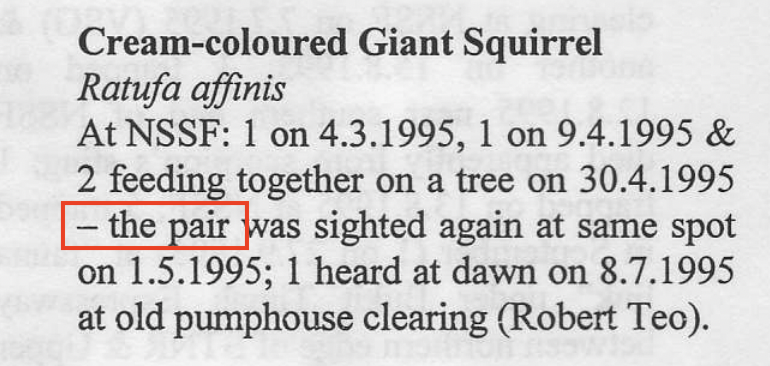

Screenshot from a 1995 issue of "The Pangolin", a now-defunct bulletin by the Nature Society Singapore.

Screenshot from a 1995 issue of "The Pangolin", a now-defunct bulletin by the Nature Society Singapore.

Yeo, 67, is one of those who believe the squirrel is still extant in Singapore, and it's not hard to tell why; he's seen the animal on no less than eight occasions.

But the last stands out. It was a rainy morning with bad lighting in May 1995, he recalls, when he saw a pair of cream-coloured giant squirrels together in a tree.

“I presume it was a male and female pair, as they are territorial and [members of] the same sex normally can’t tolerate each other,” he explains.

Perhaps because of this experience, Yeo staunchly believes that the critter still exists in the wild here.

He cites how in Malaysia, this species have been observed making use of the oil palm to supplement their diet.

“I think being rodents, their reproduction cycle is fast,” he says. That pair could have survived, multiplied, and recovered — perhaps even faster than other endangered species like the sambar deer.

“And with limited predators compared to Malaysia’s lowland rain forest, I don’t see why it should go extinct.”

Photo from David Fur/Facebook

Photo from David Fur/Facebook

Extant or not?

Yeo's last sighting was in the Nee Soon Swamp Forest, nestled deep in the Central Catchment Nature Reserve.

If that doesn’t sound familiar, it’s because it’s now a restricted area. That meant that I wasn’t going to be able to just head down and start poking around.

But it didn’t stop me from theorising.

Could that pair that Yeo saw all those years ago have survived and reproduced, like he hoped?

Was it even possible for such a large animal to have remained hidden from sight after over two decades?

I needed expert advice. For this, I wrote to Peter Ng.

Now semi-retired, he spent seven years as the pioneering head of the LKCNHM, and 18 years before that as the director of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, the LKCNHM’s forerunner.

He’s also had the fortune of having extensive close-up experience with the squirrel — which, unbelievably, was among his boyhood pets.

“This squirrel…a tragedy of our own making,” the professor writes in an email reply to my query. “Sad…can talk a bit on the phone on it if you wish.”

Johore Forest, Malaysia. Photo from William Ko/Facebook

Johore Forest, Malaysia. Photo from William Ko/Facebook

I end up making my way down to the museum to talk to him in person.

Candid and opinionated, Ng cuts a figure nearly as charismatic as the squirrel. "I realise I may be the last person to see the cream-coloured giant squirrel up close," is the first thing he tells me (after striding into the meeting room thirty minutes late).

The professor is open about his special fondness for the squirrel. As a child in the 70s, he kept a cream-coloured giant squirrel — very briefly — as a pet, courtesy of one of his mother's employees.

"Very cute…but very fierce," he recalls. It loved eggs and had an extremely soft tail, which he would stroke through its cage.

Yet for all his affection for the squirrel, Ng has no qualms about deeming it extinct.

“We are scientists, we deal with facts. A squirrel that large is unlikely to be missed… and it’s not exactly quiet. When it jumps, it’s noisy. Hard to miss," he explains.

The squirrel's population began to diminish in the 70s — but the death knell, he believes, took place in the 50s to 60s. Back then, Singapore was urbanising at an astonishing rate.

"Rubber plantations were chopped down. Our forests retreated. And we started building, building, building.”

At the same time, hunting was unregulated. People would poach the squirrel as pets or kill it as game. Ng recalls the markets of Chinatown in the old days: "You’ll see people selling everything under the sun. Flying fox, pangolins, civet cats, turtles. Strange animals… and squirrels, by the hundreds.”

Hawkers selling fresh pangolin meat. Image courtesy of Theo A. Strijker.

Hawkers selling fresh pangolin meat. Image courtesy of Theo A. Strijker.

With pressure on every front, the squirrel — opportunistic and hardy as it was — began to decline. Its population crashed to unsustainable numbers.

"So a bit of push here, a bit of push there... and we lose them."

I tell him about Yeo's 1995 encounter. “Couldn’t that pair have survived and reproduced?” I ask hopefully.

“Squirrels don’t live that long,” is his blunt reply. Even if the pair from 1995 did survive, it wouldn’t have been enough; they would likely have died out in, at best, another generation or so. This phenomenon is called "extinction debt", in which the last surviving members of a species are essentially the walking dead.

“So even if you see one — or two — it’s extinct.”

Photo from Bird Ecology Study Group

Photo from Bird Ecology Study Group

Rewriting the story

But that doesn’t mean that it’s the end of the story.

The squirrel is unlike the otter or wild boar, whose populations here are believed to have been replenished by refugees from neighbouring Malaysia. It can't recover.

But it can be reintroduced.

For years, the professor has pushed for the reintroduction of the cream-coloured giant squirrel.

The Singapore of today is a far cry from the wild game markets of the 1950s.

“We no longer suka-suka ("as one wishes", from the Malay word suka, meaning "like") cut forests down. The forest ecosystem has grown quite healthy… full of food, full of nice greenery, all protected. No hunting allowed. Nobody will consider eating a squirrel,” Ng quips.

“So now’s a good time to bring the squirrel back.”

There are considerations, of course. Studies to be done, risks to be calculated.

But Ng believes that it is possible, and with good cause.

“Almost like taking responsibility for our actions,” I volunteer. He shakes his head.

“It’s more like trying to repent for our sins. The sins of our fathers.”

Reintroduction

Ng isn’t an expert in reintroduction. For this, he directs me to Marcus Chua, who studies mammals in Southeast Asia.

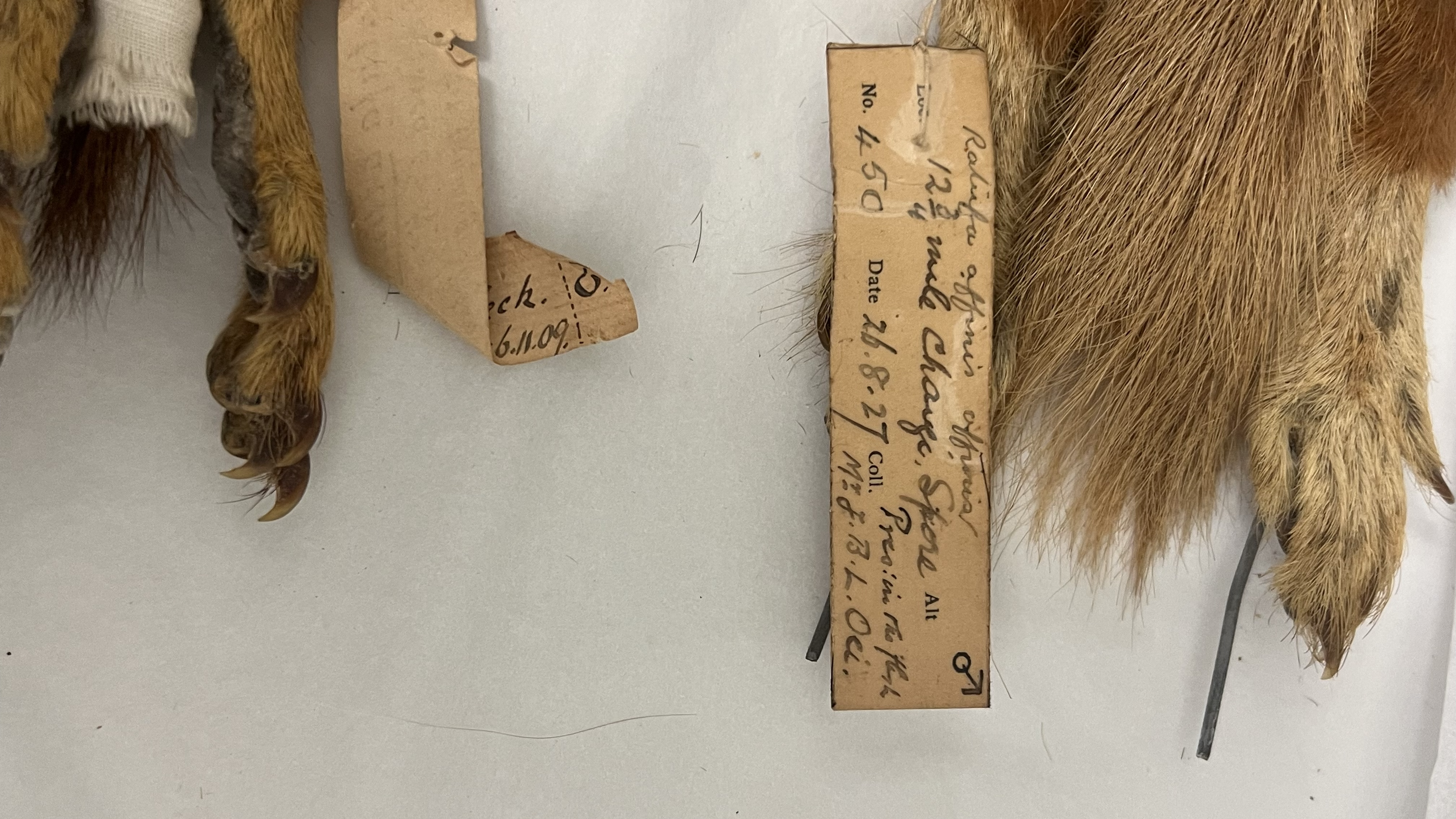

I head down to the dry collections room to meet him. Chua asks if I’d like to see the specimens.

In my infinite ignorance, I'm expecting something propped up and posed, behind a thick sheet of glass.

Instead, he opens a metal drawer that reminds me of a filing cabinet. Inside are four squirrels, laid out on thin creased paper — their fur still soft, their tiny paws outstretched. Some are over a hundred years old.

Chua is more reserved than the professor. Nonetheless, when I ask him about the possibility of reintroduction, his answer is a careful affirmative: "It's certainly a candidate for reintroduction."

The biggest concern is whether Singapore has the right habitat for the wild squirrel to thrive in. The Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Singapore's biggest continuous forest, is about 16 square kilometres large.

But this might not be enough for the squirrel. A plantain squirrel can survive at a population density of 20 individuals per square kilometre. The admittedly few studies of the cream-coloured giant squirrel suggest that it needs much lower densities of around five per square kilometre.

That translates to Singapore's biggest forest having room for about 80 cream-coloured giant squirrels.

Typically, a sustainable population would number at 500.

Photo by Ilyda Chua

Photo by Ilyda Chua

Of course there are exceptions. A smaller area could work, particularly if it's managed by humans; it could be supplemented by a captive breeding population. And the Raffles' banded langur, for instance, has been growing unaided despite its population numbering at only around 70.

Still, this would be a big step. Singapore has never deliberately reintroduced an animal before. It's unclear if we're ready.

Chua is less sentimental than Ng. He doesn't say anything about repentance or turning back the clock.

"Its place in the ecosystem would be restored," he says simply. "Now it's missing... we'd have it back in Singapore."

I think about the official specimen, Raffles' specimen, that was lost — likely hundreds of years ago. Lydia Gan, a member of the research team, had told me that the team was going to try to replace it with a specimen of their own.

"Because this squirrel is such an important part of the Singapore natural heritage," she explained.

What is broken cannot become whole again. But it can be fixed.

Revisiting the site

Despite the unlikeliness of the squirrel's continued existence, I can't resist asking if I can actually go down to the Nee Soon Swamp Forest to see it for myself.

After all, even if there's only one or two left — it could still be out there.

Chua explains that it's now restricted for military purposes; however, there's a public carpark at Upper Seletar that's basically as close as I can get.

"Here ah?" the skeptical taxi driver asks me when we arrive at the deserted carpark. It's 4pm on a weekday, an hour or so after a rainstorm. The tarmac is still wet.

There's not a soul about, as I make my way through the tiny sliver of forest that I dare to navigate, staying within metres of the carpark. There are no clearly-marked paths, just the ghost of a forest trail and bits of urban debris.

A monitor lizard darts through the leaf litter, then a plantain squirrel. Lacy sunlight slips through gaps in the foliage. I'm startled by a passing monkey, who shoots me a look of contempt.

I don't see a "no entry" sign, and no soldier emerges to demand I get out, so I go a little deeper. Push my way past dripping leaves and silk-fine spiderwebs.

And then I trip over a branch.

The snap is deafening, and I hear something large squeak and scatter, bounding through the dense vegetation. Perhaps a flash of brown — even cream? I can't tell.

I inexpertly detangle myself from the branch and squint up at the canopy looking for the mysterious animal. I wait and I wait.

But it's long gone.

Photo by Ilyda Chua

Photo by Ilyda Chua

I'll be the first to admit that I have my own selfish reasons for wanting the squirrels back. There's a unique sort of delight in seeing an adorable creature in the wild in hyper-urban Singapore; just ask the 100,000 members of Singapore Wildlife Sightings.

There's also a feeling of nostalgia for what is gone, even though I haven't seen it firsthand.

Sure, there are practical reasons. Like any other animal, it plays a role in the ecosystem; as a charismatic species, it might increase awareness of wildlife, perhaps even foster an interest in it.

But for the most part, my desire is far simpler and more base.

Photo from Leslie Loh/Facebook

Photo from Leslie Loh/Facebook

I make my way out of the forest. In the dense lushness, it's not difficult to imagine that the squirrel might have been there. A pale shadow, leaping between the branches; an elusive member of a species that's as good as extinct here.

And that one day, it might not have to be any more.

Top image courtesy of Mike Hooper/Viator Photography, via Nature Society Singapore, and Chow Khoon Yeo/Flickr

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.