Prominent banker and philanthropist Wee Cho Yaw passed away on Feb. 3 at the age of 95.

The son of the founder of United Chinese Bank, which later became known as UOB, Wee took over the reins in 1960 when he was 31. It marked the start of an extraordinary banking career that would span six decades.

With Wee at the helm, UOB's expanded from 75 branches and offices to more than 500 globally. The bank's assets grew from S$2.8 billion to a staggering S$253 billion during Wee's term as group chairman and CEO.

PM Lee with Wee at UOB's 80th anniversary celebration. Photo via Lee Hsien Loong/Facebook

PM Lee with Wee at UOB's 80th anniversary celebration. Photo via Lee Hsien Loong/Facebook

A large part of UOB's early growth stems from its acquisition of other banks after it was publicly listed.

It's started in 1971 when the bank bought a controlling stake in Chung Khiaw Bank which was established by one of the Tiger Balm brothers. The bank followed up with Far Eastern Bank in 1984, and Westmont Bank and Radanasin Bank in 1999.

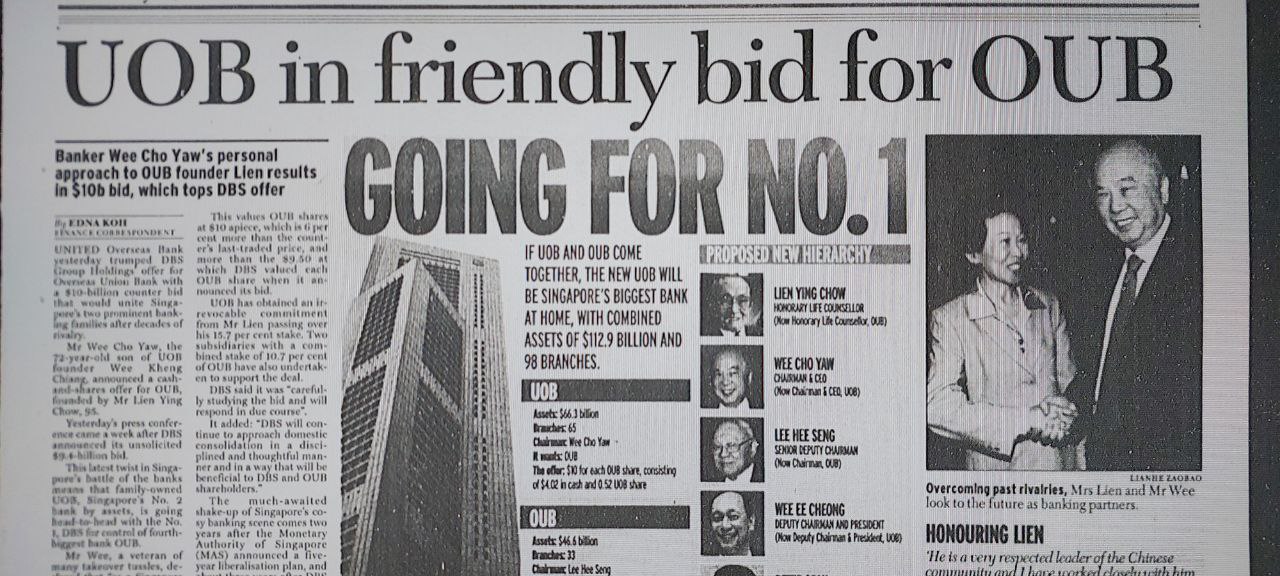

But it was the bank's takeover of OUB in 2001, the biggest acquisition of Wee's career, that remains UOB's most famous to date -- partly due to the parties involved, partly because it offered the public a glimpse of the machinations that typically take place behind the scenes, but notable for Wee's ingenious use of the personal touch.

Every Singaporean bank either a bidder or a takeover target

To set the scene, we return to the start of the new millenium: 2001.

It'd been two years since Singapore government started to liberalise the banking sector in hopes of spurring competition and expanding the range of banking services that were available to the public.

One of its goals was to improve the capacity and capabilities of local banks.

In 2001, Singapore had twice the number of local banks compared to today; it was an uncertain time for them all in a market which the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) famously said had room only for two big banks.

And so it was eat or be eaten. If you weren't a bidder, you were a target to be gobbled up.

"The fact that they are bidding and being bid for proves not just that the smaller local banks are vulnerable, but also that the bigger ones themselves feel insecure, and rightly so," said then-chairman of the MAS Lee Hsien Loong on Jun. 29, 2001.

Speaking to members of the Association of Banks at their annual dinner, Lee assured them that consolidation of local banks was a positive development, one that was very much welcomed by the MAS.

Local banks needed to achieve economies of scale to be competitive, said Lee. Otherwise, they would be like "bonsai plants, root-bound by the small pots in which they grow".

The bid for OUB: The race to be #1

Lee's speech couldn't have been delivered at a better time.

Just a week earlier, DBS dropped a bombshell, announcing that it was making an unsolicited bid for OUB; the bank was prepared to offer S$9.4 billion in cash and shares.

DBS' offer, if accepted, would have filled a gap that it was sorely lacking, noted Straits Times financial correspondent Edna Koh:

"...the takeover of OUB fills the Malaysian gap in [DBS'] ambitions to become the best bank in Asia. With OUB, DBS -- which has a miniscule presence in Malaysia -- gains 12 branches."

The combined DBS-OUB entity would have also make it the third largest commercial bank in Asia, outside of Japan and Australia.

But then, came another challenger.

Three hours before Lee took to the rostrum to address the Association of Banks on Jun. 29, 2001, UOB held a press conference to announce its counter-offer: S$10 billion in cash and shares, after reaching an agreement with the controlling stakeholders of OUB.

UOB was gunning for pole position. Its offer, if accepted, would make it the biggest bank in Singapore with combined assets of S$112.9 billion and 98 branches.

Day vs Night

Right off the bat, the choice of approach by UOB and DBS was as different as day and night.

The Straits Times chose to highlight the personal touch that Wee wielded in its front page coverage the next day: His "friendly bid" underscored by a personal visit to OUB founder George Lien Ying Chow, a genteel mission to convince the Liens to join forces so that both banking families could continue to "nurture the entrepreneurial spirit".

That and Wee's offer to make Lien the Honourary Life Counsellor of the combined UOB-OUB entity, a move borne out of a desire to respect the latter and his stature in the Chinese community.

An accompanying photo of Wee shaking hands with Lien's wife, Margaret -- rivals turned banking partners, read the caption -- was contrasted with a curt quote from Margaret about her husband's response to the unsolicited DBS offer:

"He was very upset, but he did not break down, not at all."

The Goldman Sachs report: "OUB shareholders should chastise its board and management"

Both Wee and Lien came from banking families, a shared connection that Wee could have (and likely would have) used to his advantage in his negotiations with Lien.

In fact, it was precisely this point that Goldman Sachs, adviser to DBS, pounced on in their analysis of the UOB offer, which as history would show, did little to advance DBS' cause.

The investment bank did not mince its words in its analysis, piling on with blunt candour that was as American as a Texan cowboy on his first rodeo.

In Goldman Sachs' analysis of UOB's bid, which was subsequently presented to potential investors and shareholders in Europe, it claimed that the integration of UOB and OUB would likely be "disrupted by decision paralysis and infighting".

It also claimed that UOB's offer was "daring" because it was "designed to keep family control intact without regard for shareholder value".

That wasn't all.

Goldman Sachs went on to suggest that the OUB board and management deserved some form of punishment.

"OUB shareholders should chastise its board and management. The controlling shareholder values 'face' over real value maximisation. Should that be equally true for the other 85 per cent that has invested hard-earned savings in this bank?"

DBS chairman: "What has happened is not reflective of the way DBS does things"

As you can imagine, the report did not sit well with UOB and OUB when they found out about the report's existence.

While the report's comments were "fairly tame by international banking standards", reported CNN, they struck a raw nerve, prompting UOB and OUB to make complaints to MAS and reportedly threatened DBS with legal action.

The report also did not sit well with the chairman of DBS Group Holdings, S Dhanabalan, who was "very angry and upset".

Dhanabalan wrote separately to Wee and Lee Hee Seng, chairman of OUB, to explain that there was no basis to the report's claims. Neither was there basis for the suggestion that OUB's directors did not act professionally in the discharge of their fiduciary duties.

In fact Lien's appointing of Lee Hee Seng, an outsider, as OUB's chairman was the former's attempt to "turn away from nepotistic hiring practices".

The report, explained Dhanabalan, was written by an overseas office of Goldman Sachs and thus, was not subjected to DBS' protocols.

"I am very angry and upset. All my board members are likewise angry and upset," wrote the former Cabinet minister.

"What has happened is not reflective of the way DBS does things. However, we accept responsibility."

Dhanabalan assured both parties that he would send a "high level team" to Europe where the report was distributed and withdraw the offending statements.

His letters and the replies from Wee and Lee were subsequently published in a full-page advertisement in The Straits Times, along with a promise to pay both UOB and OUB S$1 million each to be distributed to charities of their choice.

The full-page advertisement which you can view at the National Library.

The full-page advertisement which you can view at the National Library.

OUB ultimately decided to take up UOB's offer. And that's how Wee Cho Yaw won the biggest bank takeover of his career.

Top image adapted from NewspaperSG.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.