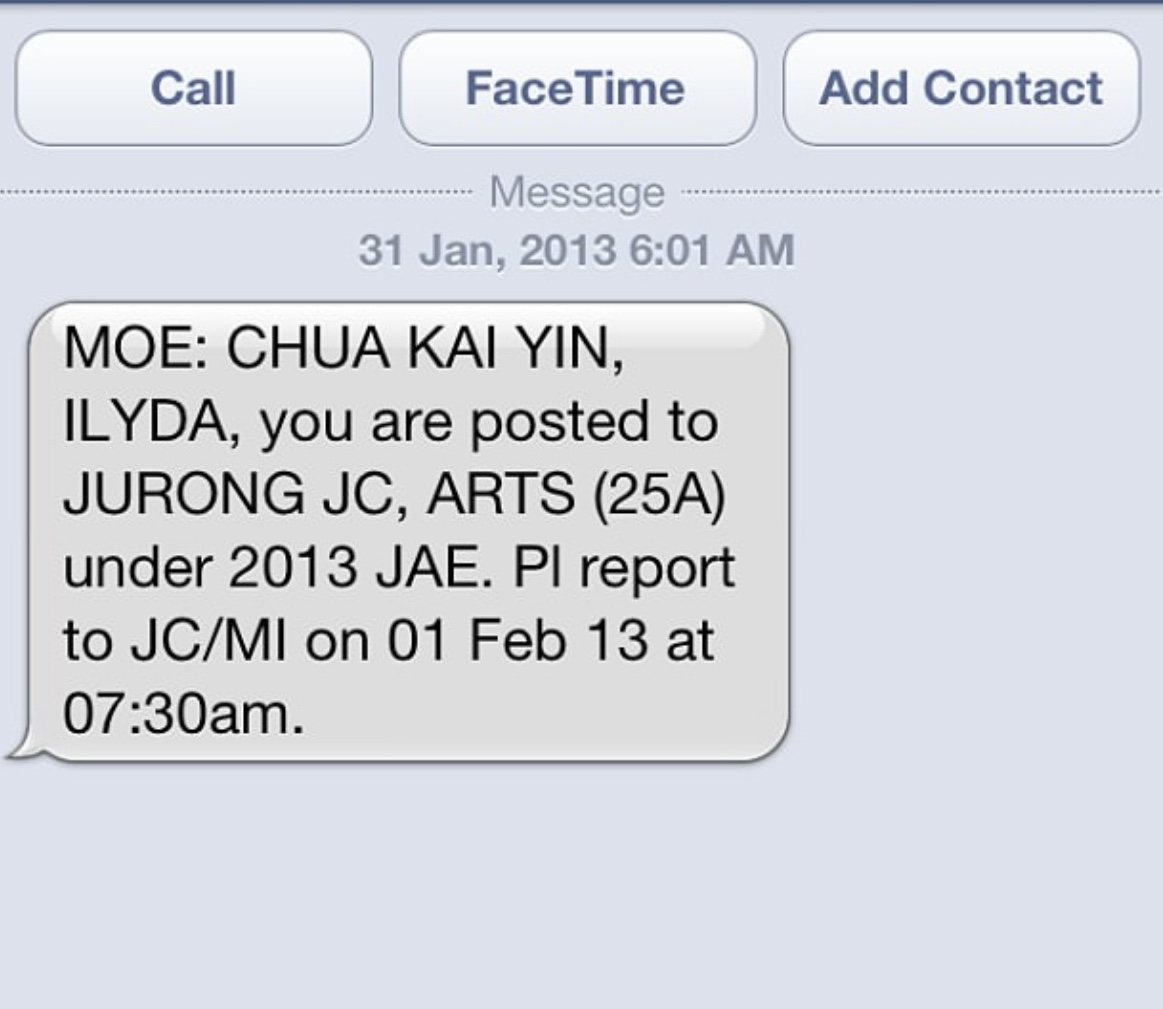

O-Level results season is upon us.

It's the time of year when your news feed gets flooded with feel-good platitudes about how polytechnic is just as good than JC, or that your O-Level results don't matter in the grand scheme of things, or that do you know how well our ITE grads are doing these days?

To all of these, I respond, sure. But I'm still an advocate of the JC system.

I went to a JC, and I'm of the increasingly socially unacceptable opinion that for all the advantages of polytechnic life, JC was undoubtedly the better option for me.

Bring on the pitchforks. But before that, hear me out.

Reason #1: JC gives you time to think

The fact of the matter is, 16 is a really young age to be deciding what you want to do with your life.

When I was 16, my only ambition in life was to marry Edward Cullen.

JC is often lambasted (with plenty of condescension) as an extension of secondary school, where students learn no real-life practical skills.

And they still have to wear uniforms.

But why is that a bad thing?

Sure, most of the stuff on the JC curriculum is theoretical. But that's the whole point of pre-tertiary education: to improve your cognitive skills, your problem-solving skills, your social skills.

In JC, I studied geography, literature, and economics. (Also math, but I have very little memory of that.)

We even put on a play for Literature. So fun, so useless, don't regret it at all.

We even put on a play for Literature. So fun, so useless, don't regret it at all.

Do they have any real place in my current career? No, not really.

But I gained plenty of practice in essay-writing, debate, and time management.

I enjoyed learning things I was interested in, without needing to consider its attractiveness in my future resume.

I also now know quite a lot of facts about volcanoes. Which in itself isn't very useful, but it's fun to know, and always makes for an interesting conversation.

Most importantly, by the time I graduated JC at 18, I had two extra years of childhood.

During this time, I was able to carefully consider my skills and interests with some semblance of maturity.

I grew out of Twilight and decided I wanted to pursue journalism.

Which is why, I guess, you're stuck reading this.

Graduation day, circa 2014.

Graduation day, circa 2014.

Reason #2: JC is cheap

I come from a working-class family. So it wasn't particularly surprising when my parents told me they'd rather I enter a JC.

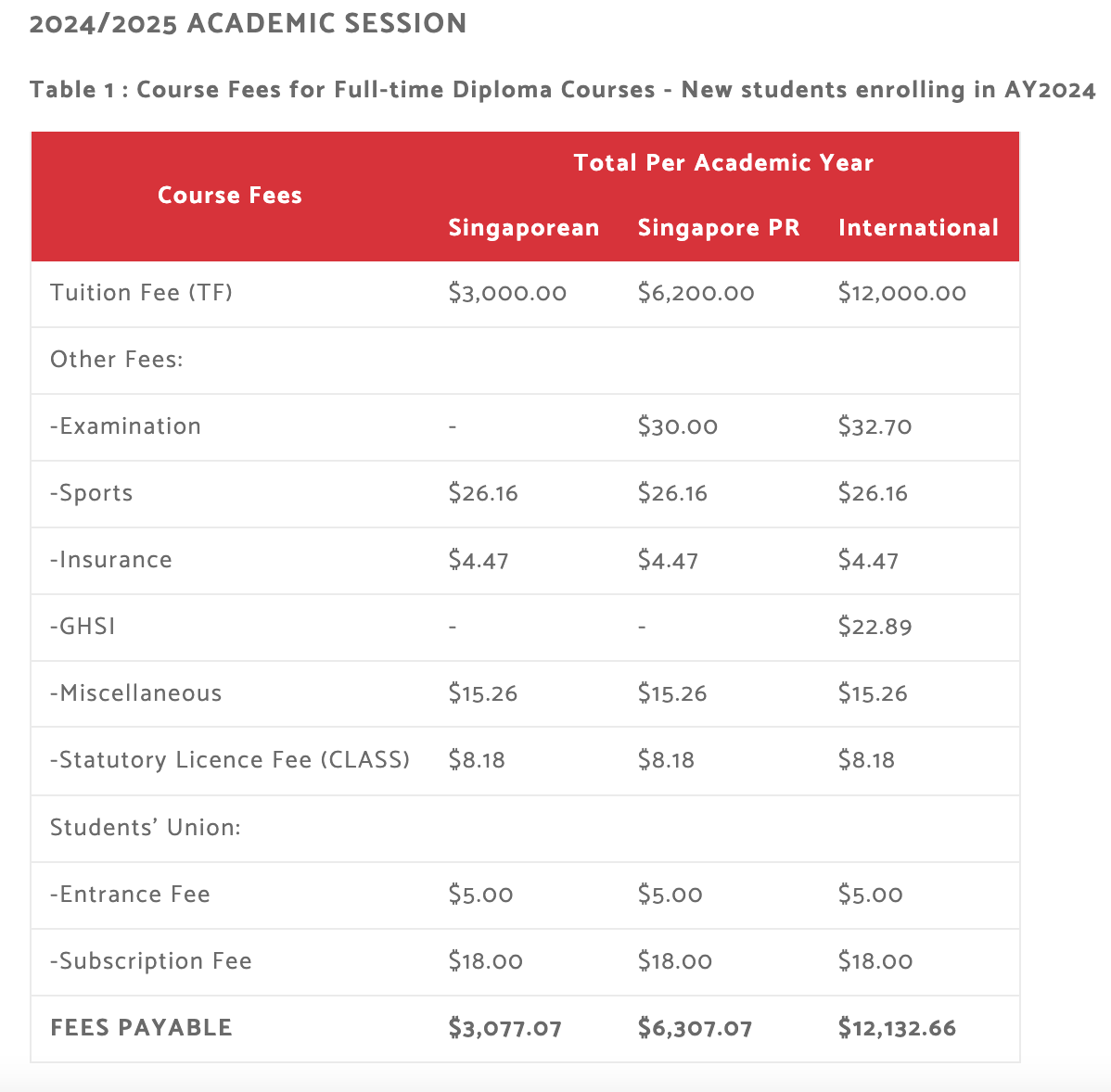

As explanation, here's a screenshot of the latest tuition fees from Singapore Polytechnic:

In comparison, here are the school fees for a typical Singaporean student who attends Yishun Innova Junior College, according to the MOE website:

I'm not saying that polytechnics aren't value for money.

The reality is that the monetary value of a diploma — not to mention the amenities and experiences you'd get in a polytechnic — far, far outweighs what you'd get in a typical neighbourhood JC, like the one I attended.

But in a family where money is tight, it's not about value. It's about overall cost.

Food at polytechnics also tend to be more expensive, not to mention the cost of buying your own clothes versus cycling through the same three sets of school uniform.

Had I chosen to enter a polytechnic, my parents would have had to struggle.

I most likely would have had to take out a loan. Graduating in debt, in turn, would've discouraged me from pursuing further education.

But because I chose to go to a JC, the financial impact on my family was nearly negligible.

These days, it's become increasingly the norm for polytechnic graduates to go to university after.

MOE figures from 2023 show that about one in three polytechnic graduates matriculate at local universities.

Of course, it's great that more polytechnic graduates are able to pursue further studies, something which was once upon a time a privilege granted to a rare few.

But needless to say, the cost of getting a diploma and a degree — versus an A-Level cert and a degree — is just incomparable.

Reason #3: Opportunities

"Sure, Ilyda," you might say, "you paid S$33 a month. But you also graduated with an A-Level cert and zero vocational skills. Instead of wasting another four years studying for a piece of paper, wouldn't it make more sense to get a diploma and start working and earning money right away?"

To which I answer: sure, maybe.

But going out into the workforce, then and now, with just a diploma would've meant starting out with a lower pay than my degree-holding counterparts.

This isn't conjecture either.

According to 2022 Labour Front statistics, the median gross monthly income for diploma and professional qualification holders was S$4,117 — significantly lower than the S$7,233 that degree owners earn.

By going to a JC and taking the conventional A-Level route, I was put on a default track to university.

That helped me obtain the fancy piece of paper that would (eventually) allow me to land a job that paid more.

While uni isn't cheap, given the net benefit, I felt it was a fair deal.

And last month — almost four years after graduating — I paid off the last of my debt.

That's where I am now.

And I doubt I'll ever regret it — even if I did "waste" two years of my life scrutinising differential equations and dead poets.

JC was better — for me

Of course, JC is far from a perfect institution.

Critics will talk about the unnecessary stress it places on young tender minds. The way it — perhaps unfairly — overvalues the very limited skillset of rote memorisation and lower-order language ability, which I was lucky enough to possess.

And some JCs are, potentially, hotbeds of elitism.

But that doesn't mean that the JC system is irrelevant. It certainly doesn't mean that polytechnics are better than JCs, as it's become increasingly popular to preach.

For the most part, I have good memories of my life in JC. It was tough and stressful and the days were long, but I enjoyed the freedom to choose what subjects I studied, and my teachers were caring.

I still remember my form teacher for her contagious passion for geography (the reason why I still remember my volcano facts now), and my economics teacher for how she'd constantly laugh at our "antics".

Our literature teacher, on the other hand, was a jolly old angmoh guy who'd bang loudly on his desk whenever we started to drift off in the middle of his spirited declamations of George Eliot and Kazuo Ishiguro.

"Don't you dare yawn!" he'd exclaim. "This is good stuff!"

With my form teacher at prom.

With my form teacher at prom.

And while the extra-curriculars in a JC can't compete with that in a polytechnic, I have fond memories of what we did get to do: our Literature play, our Geography field trips, our GP debates.

Most importantly, I was able to live my teenage life to the fullest.

Call it selfish, but you only get so many years of your life to live without thinking of adult things like job interviews and promotions. To this day, those extra two years are something I treasure deeply.

The Ministry of Education says that every school is a good school; I think it should have been fine-tuned to say that every school is a good school for someone. (In fact, Minister for Education Chan Chun Sing has repeatedly said something like this over the past year.).

Sure, my JC might not have been a good school for plenty of people. Yourself included.

But for all its quirks — it was a great school for me.

Top image from Ilyda Chua

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.