Nathanael Koh is no ordinary kid.

Having graduated with first class honours in music composition from the Australian National University (ANU) in 2023, the young boy already has a myriad of accolades in the bag.

He's clinched a Bachelor of Music from the Australian Guild of Music, a diploma in music theory from Trinity College London, and serves as a composer for two local orchestras.

He is 13 years old.

But age has never been more than just a figure on Koh's birth certificate.

Prodigy

A gander at Koh's YouTube channel will reveal scores of videos offering math tutorials, including worked answers to Oxford University Test Admissions from 2007 to 2021.

This is just a glimpse into Koh's remarkable mind — one that set its owner on a fast-track in the academic arena.

When we asked Koh to give us a brief rundown of his academic journey, he rattled off a list of impressive milestones, as casually as one would recount what they ate for dinner yesterday.

Koh started primary school at the age of three.

At four, he tackled Primary One Mathematics.

When he was seven, he went on to Secondary One Mathematics, swiftly followed by GCE O-Level Additional Mathematics when he hit nine.

He then progressed to GCE A-Level Mathematics and O-Level Chemistry and Physics at the age of 10, going on to study Mathematics at New Zealand's University of Canterbury when he was 12.

Which led him to who he is now, the youngest graduate of ANU, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

But things haven't always been smooth sailing for him.

A change in environment

Koh was diagnosed with Global Developmental Delay (GDD) at the age of one.

The term is used to describe a condition whereby the child experiences significant delays in reaching certain developmental milestones compared to kids their age, such as walking, talking, moving, and interacting with others.

He failed all his developmental milestones, recounted his father, Chris, to Mothership.

Koh never crawled, couldn't walk when he reached two, and only had minimal speech abilities by the time he was four.

He ended up undergoing early intervention therapy three times a week at KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH).

Without any subsidies and each session setting them back S$170, the regular sessions took a toll on the family's finances. And without seeing any improvement in Koh, it led to "lots of money wasted".

"That was 12 years ago, when Singapore didn't have much support [for such conditions]. People looked away as they are afraid of diseases. We were very much alone in figuring out how to navigate this disabled space."

"The doctor said no one ever grows out of GDD. So it's better to move on," Chris said.

The family up sticks and moved to New Zealand, in search of greener pastures and "cold clean air" to provide Koh with "natural therapy".

Chris, who is a scientist and has a PhD in Life Sciences, added that it's not just the air but also the organic crops, spring water, silence of the night, pine forest walks and waterfall —these elements of nature were helpful to Koh's condition.

However, he also highlighted that the nature therapy is a slow process and it only works when the child is young when their brain is still growing.

He only made the decision to move to New Zealand after reading scientific journals for years.

Image from Nathanael Koh's Instagram

Image from Nathanael Koh's Instagram

For all the troubles of his earlier days, Koh has grown up to be someone who looks life in the eyes and challenges it with the cards he's been dealt.

"Too young"

"I didn't choose Australia, the university there chose me," said the boy, who explained that he was rejected from Singaporean universities on the premise of him being "too young".

According to his father, Koh needed to "do his Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE), GCE O-Levels and GCE A-Levels in that sequence" in order to gain entry into local universities.

"But then Professor Kim Cunio at ANU said he would take me in based on my merit and not my age," Koh shared in a post on ANU's website.

Image from Nathanael Koh's Instagram

Image from Nathanael Koh's Instagram

Entering university on your own might already seem daunting to some 18-year-olds, but Koh carried himself with poise and confidence that belied his age.

He said he also had support from faculty members, such as the associate dean, who met with him every week to make sure "[he] was mentally fine".

As for friends, the preteen had no qualms blending in with folks almost twice his age in his music composition course.

"There was no barrier because we all spoke music, played music, and composed music together," Koh shared.

The members of the Singapore Students Association (SSA) also provided him with a place to go when he was homesick.

Music is his first love, mathematics his second

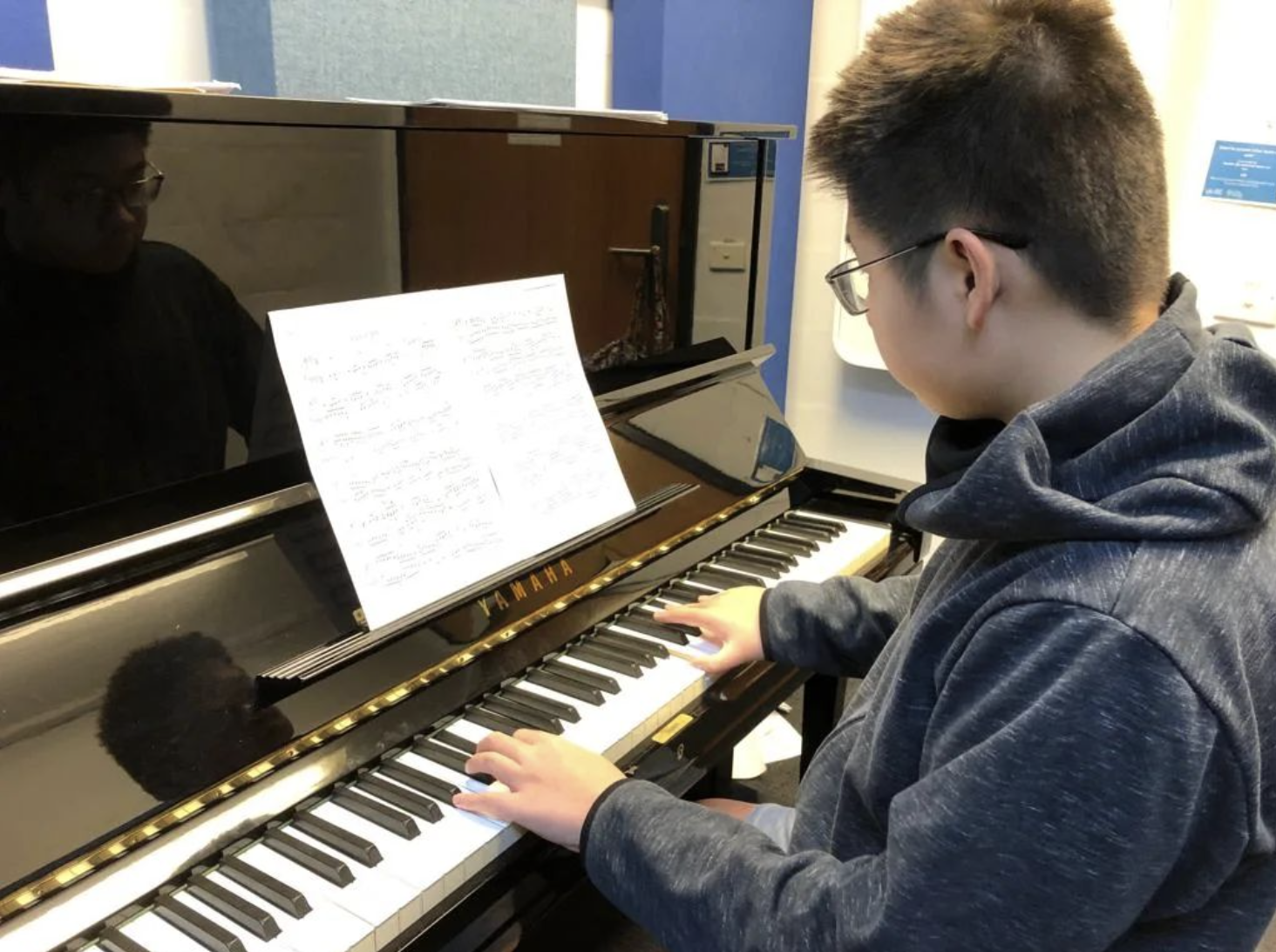

Although he had problems communicating when he was younger, Koh eventually found his voice through music.

Understanding that music played "an important part in brain development", Chris and his wife made sure that their son grew up surrounded by melodies and rhythms.

"We tried getting him to play music, but his body was weak and unable to play," said Chris.

Since Koh's fingers weren't strong enough to press the piano keys when he was seven, his then music teacher taught him music theory instead.

He began developing his practical skills from the age of eight onwards, practicing the clarinet at the same time — an alternative instrument which was easier on the fingers.

In one-and-a-half years, Koh went from a beginner in music theory to getting a music diploma from Trinity College London, his father shared with pride.

Image from Nathanael Koh's Instagram

Image from Nathanael Koh's Instagram

But while his parents understood the full extent of their son's brilliance, the rest of the world didn't.

"We came back to Singapore when [Koh] was around eight to look for a music theory teacher. We approached a lot of teachers. All told us they will not teach a kid," shared Koh.

"We spoke to an arts administrator when he was nine. He scoffed at us and mocked [us], [asking if] Nathanael could even read music notes. This is the difficulty in Singapore."

That was until Singapore's Cultural Medallion recipient, Phoon Yew Tien, agreed to take Koh under his wing.

"Mr Phoon was key in Nathanael's development journey. He introduced [Koh] to the Singapore’s Kids’ Philharmonic Orchestra where [Koh] was appointed as the composer in residence at age of nine," said Chris.

Next up, a PhD

"Music will always be my first love, and Mathematics my second," Koh had declared.

He has, however, found a way to combine the two in an interdisciplinary PhD at ANU next year.

The prodigy is looking to embark on the post-graduate degree, which will "weave together mathematics, computer programming using Python, and musical composition.

People have always found a way to marry math and music through the ages, said the boy, citing figures like Pythagoras, Albert Einstein, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

"Including me," he joked.

"Both [math and music] are the world's universal languages," said the kid, who passionately let slip that humans might even wield these as modes of communication for extraterrestrials.

Not everyone his age can keep up with what Koh says, but the child genius — who plays Tetris and chess for fun — isn't afraid of missing out on his childhood while being too busy looking into the horizon.

"I'm not losing out on my childhood because for me, childhood is about exploring the world and learning new things about the world. And my childhood is about learning. I sense everyone has their own path. They might enjoy it, they might not enjoy it. I, personally, enjoy my own path."

When asked what the road ahead was like for him, Koh said he's thought about being a musical researcher in the future, but he's yet to iron out the details.

He added that he's also considering going into medical school, but who knows?

"I'm terrible at extrapolation," the kid said.

Top images from Chris Koh and Nathanael Koh's Instagram

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.