In June 1977, Lim Bong Huat left for work. He secured the windows of his Marsiling Drive flat, locked the doors and headed out.

When he returned at 6:30pm, his entire house had been ransacked.

Despite the state of the house, there was something quite strange about the scene. The door and windows that Lim had made sure to close before he left for work were completely intact.

A similar incident had happened a few weeks prior, to Lim’s neighbour, Fong Shi Ge.

Fong came back to find his house in disarray.

His camera and a S$600 cassette recorder had been stolen, and so had his passport and bank passbook.

Not only that, the robber had then proceeded to withdraw Fong’s entire savings in that passbook, S$4,000, on the same day by forging Fong’s signature on the withdrawal slips.

Despite the chaotic state of the house, just like in Lim’s place, the front door and windows were completely intact.

The only sign of a break-in was quite a ways from the front door. In both cases, the covers on their rubbish chute had been torn open.

Feasibility

Fong was taking no chances. Convinced that there was a rubbish chute fiend on the loose, he resorted to unorthodox measures like securing the garbage chute door with a padlock and using a car steering lock to padlock the chute cover to the kitchen window grille.

Despite Fong’s insistence on the chute’s culpability, there were still some doubts.

According to The Straits Times, while police investigations had pointed to the rubbish chute being the only possible means of entry, they were quite sceptical of how feasible such a break-in would be.

Their scepticism was mainly due to the narrowness of the chutes (23cm by 30cm) and the tremendous risk posed to the would-be burglars if they had slipped during the heist.

A possible scenario the police were considering was that the burglars might have had a duplicate key, entered the house, and then damaged the chute to give the false impression that the robber had come in through the chute.

While the authorities might not have conclusively ruled it as a rubbish chute burglary just yet, capitalism wasted no time.

Lion Tower Enterprises wasting no time.

Lion Tower Enterprises wasting no time.

All this culminated in quite a fantastic investigation by The Straits Times.

One of their team members, Tan Ban Hoe, crawled in through a rubbish chute into the main vent. Tan found that the air vent at the top of the shaft (28cm wide by 0.84m long) was large enough for a medium-sized man.

On opening the chute, Tan found “no difficulty” in prising open the chute cover due to the “ample space” in the main shaft.

And that was for a man with “45cm broad shoulders”, as the reporter put it — quite wide, and a nice little boost to his colleague’s ego.

Here are some absolutely brilliant photos of Tan.

Reverse Sadako.

Reverse Sadako.

A day after the article was published, HDB released a statement announcing they were rectifying the chute openings in the affected block.

According to them, the chute openings at Block 22 were an “unusually large” 75cm by 28cm compared to a regular chute opening of 75cm by 20cm.

Cool, an anomaly, one which had been more or less taken care of by HDB. So ends the chapter on Singapore’s little rubbish chute kerfuffle.

Chute load of cases

Unfortunately, the golden era of chute burglaries was still to come.

In 1988, there were about five cases in three months of chute break-ins.

From February to May 1990, over 20 flats were ransacked using the chute method.

The method of chute break-ins had also evolved. Unlike the pioneer cases in the 70s, where the burglar would have descended from the rooftop vent, some of these new cases were chute-to-chute afflictions.

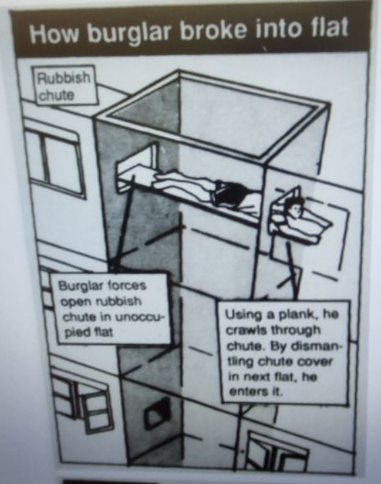

Here’s a really nifty graphic by ST showing one such incident in Yishun Ring Road.

The graphic was used to describe one specific break-in at a sixth-storey flat in Yishun Ring Road.

The police detailed how absurdly dangerous this style of break-in was in that Straits Times article:

“He could have been killed if he had slipped from the plank or suffered serious injury if someone had thrown a load of garbage from one of the higher floors.”

The police also pinpointed a few locations that saw such break-ins.

New housing estates such as Yishun, Bukit Batok, and Simei were targeted more due to the higher number of vacant flats.

But just because you had neighbours didn’t mean that you were safe.

On May 18, 1990, Steven Ang forced open the chute covers in his own flat and climbed through it to his neighbour’s apartment.

However, as he was ransacking the place, he heard a sound near the front door, so he quickly went to latch it and skedaddled out of the window back to his own house.

The police later caught him.

So how do you stop it?

The relatively steep incline in cases didn’t last long. In fact, reports of such cases became almost non-existent from even the mid-90s onwards.

There were many factors, of course. Communal trash chutes probably severely lessened chute-crawling incentives for would-be burglars, because why not just take the stairs instead?

But the prevailing direct solution recommended by authorities followed the Lion Tower train of thought.

Locks.

The police advised flat owners to install locks on their chute covers. According to them, the initial methods involving coming up from rubbish chutes had been mostly mitigated because HDB and the police had “worked closely” to ensure that all chute doors on the ground floor were locked.

They also noted that all chute robberies had occurred in homes that had not locked their chutes.

Complete eradication of the crime, though, probably needed more than a police advisory. It required the widespread adoption of lockable chutes.

Enter HDB (only by the front door, and legally).

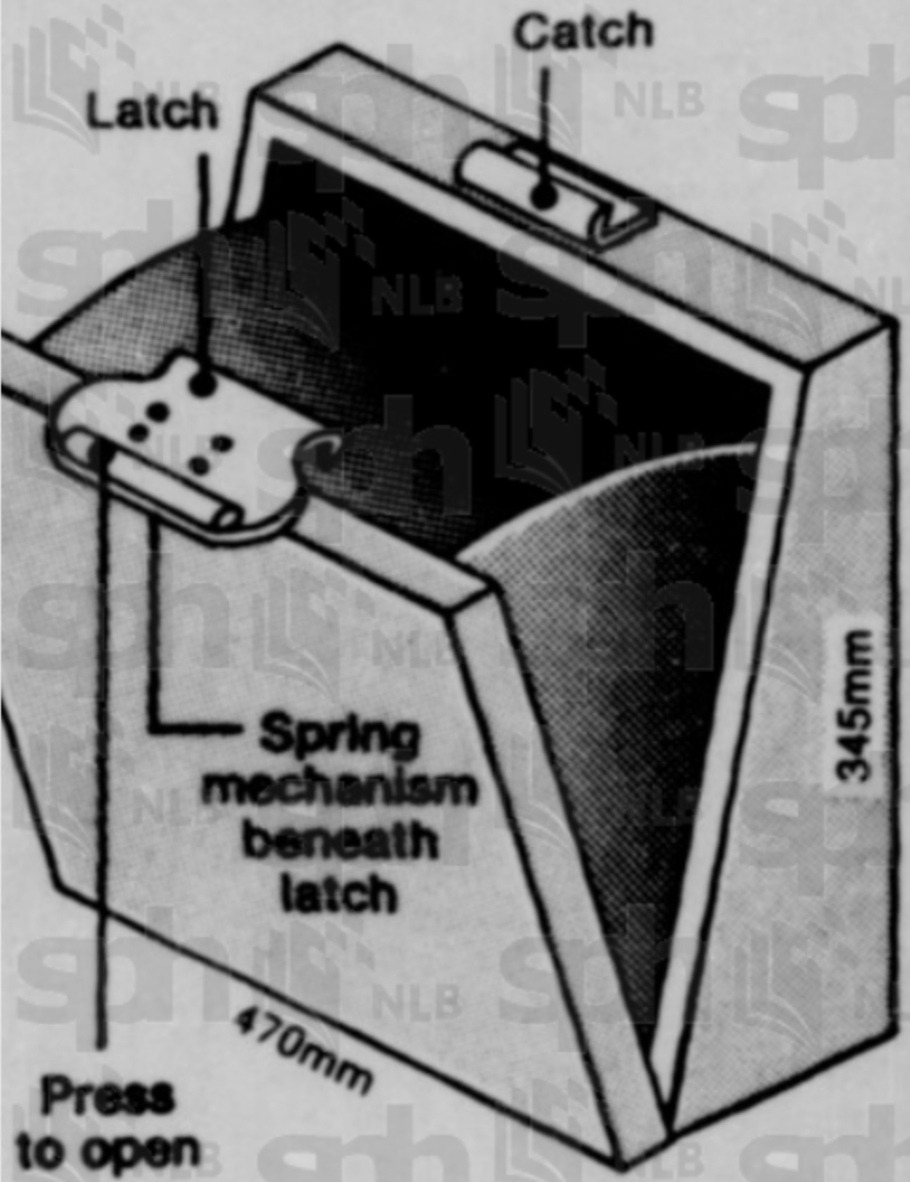

HDB introduced self-locking chutes in about 7,000 new flats back in 1989.

Image from Newspaper Sg/The Straits Times

Image from Newspaper Sg/The Straits Times

You might be familiar with the system, but it basically ensured that the chute snapped shut automatically whenever it was closed and that it could only be opened from the outside.

It would eventually be introduced in all new flats. Unfortunately, there were no plans to install these chutes in existing blocks, but HDB did provide a list of suppliers offering these locks.

The locks, inclusive of installation, would cost somewhere between S$20 to S$50.

It might not be that much in the grand scheme, but I know where they could have gotten it slightly cheaper.

Top photo from The Straits Times via the National Library Board & Ilyda Chua

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.