I've been fortunate enough not to have lost anyone close to me in my first 26 years on this earth.

That's not to say funerals weren't a common scene in my life. As I grew older, so did distant uncles and aunties, and family friends.

I'd still pay my respects, but usually just as an onlooker to guests in muted clothes expressing their condolences, or as a listening ear to the family of the departed sharing snippets of history.

A couple of years ago, I was at a relative's funeral — an uncle who I saw every year, who I occasionally joked with but never had a proper conversation with — when I curiously asked my mum: "Do you think [the deceased] would have wanted a funeral?

It is, after all, who the funeral was for, right?

Losing my loved ones

I lost two very close to me — my childhood dog and my paternal grandma — in the final week of September 2023.

They were both in their golden years. My dog (and best friend) Odey was 17 and my paternal grandma, who took care of me while I was growing up, was 94 when they passed, yet I could never fathom losing them.

Odey fell ill two weeks before he passed, and during that time, his sickness advanced so quickly that I could not internalise what was going on.

All I knew I had to do was to make sure he was comfortable as he lay helplessly, awaiting his final day.

Taking care of Odey (right) in his last days.

Taking care of Odey (right) in his last days.

I can't quite explain what it's like watching your best friend of 17 years' breath grow heavier and heavier as his tongue turns purple. I looked into his eyes, hoping he knew I was there and God I hoped he did.

The last day — Sep. 22, a Friday — felt like mere seconds. I'm not sure how long it took, but it was probably half an hour or so before he drew his last breath and his chest became still.

The following Monday, my grandma awoke at 5am distressed. She pointed at her throat, trying to communicate to my eldest aunt that she couldn't speak.

In the early part of the morning, the family chat was activated. By the time I met her at the hospital at about 11am, she was in a comatose state.

The doctors later revealed that a vein on the side of her brain had burst, causing a stroke. She soon fell into a deep sleep which she never woke up from.

The last time I met her was two Saturdays before she departed. It was at one of our family's irregularly scheduled Saturday dinners (which used to be a regular thing before the pandemic).

Lately, I hadn't been very consistent with meeting her. Between my holidaying and work on the weekends, I'd missed three or so dinners since July.

But I'm so thankful we all gathered that day, my aunts and uncles, my cousins and their kids, chaotically around the dinner table like we've done since before I was born.

I checked up on how she was faring in Boggle and Chinese checkers, games she picked up earlier this year to cope with her dementia. She complained that despite trying so hard, she still lost to her helper in a game the day before.

Grandma having a game of Boggle.

Grandma having a game of Boggle.

"Continue practising and I'll play with you next Saturday," were the last words I said to her before I left.

"Wake up and I'll play Boggle with you when I'm back," was the last thing I whispered to her when I met her next — in the hospital.

I left for a three-day work trip the next day. On Wednesday, Sep. 27, I received a text: "Ma is with the Lord".

Wake? Funeral? Cremation?

I called my dad right when I saw the message and before he hung up, he said: "I'll keep you updated about the funeral."

That evening, my aunt texted the address of the wake venue in our family chat.

With my limited experience with funerals, I didn't know what to expect. I wasn't even sure what the difference between a wake and a funeral was.

I turned to my colleagues and asked distressingly what the difference was. Thoughts quickly ran through my head:

Was I supposed to meet them at the morgue?

Is the funeral happening right after she was pronounced dead?

Am I missing anything?

Most of them replied with half answers, unsure themselves and speaking from the experience of that one funeral they attended a couple of years back.

I paused to think more rationally about my decision to book an earlier flight out and Googled:

"What are the arrangements after someone dies in Singapore?"

Multiple results came up.

One cleared up why it took my aunt a couple of hours to update where the wake was held — certifying the death and obtaining a death certificate — basically all the administrative work the hospital had them do.

Only then could they arrange a funeral.

But it wasn't so straightforward. My grandma was not religious, so what funeral was I coming home to?

In Singapore, there are different funeral traditions for Muslims, Buddhists, Taoists, Hindus, Christians, and Catholics.

The differences are in the way families choose to say goodbye to their loved ones: some with performances, colourful lights and loud chants, others with just a simple prayer and a quick send-off.

I arrived home to a Christian funeral, spanning three days at the ulu Singapore Funeral Parlour in Tampines. The wake wasn't flashy — there was a pastor every evening and catered food during lunch and dinner. No one had a role, per se, we just all helped out wherever we could.

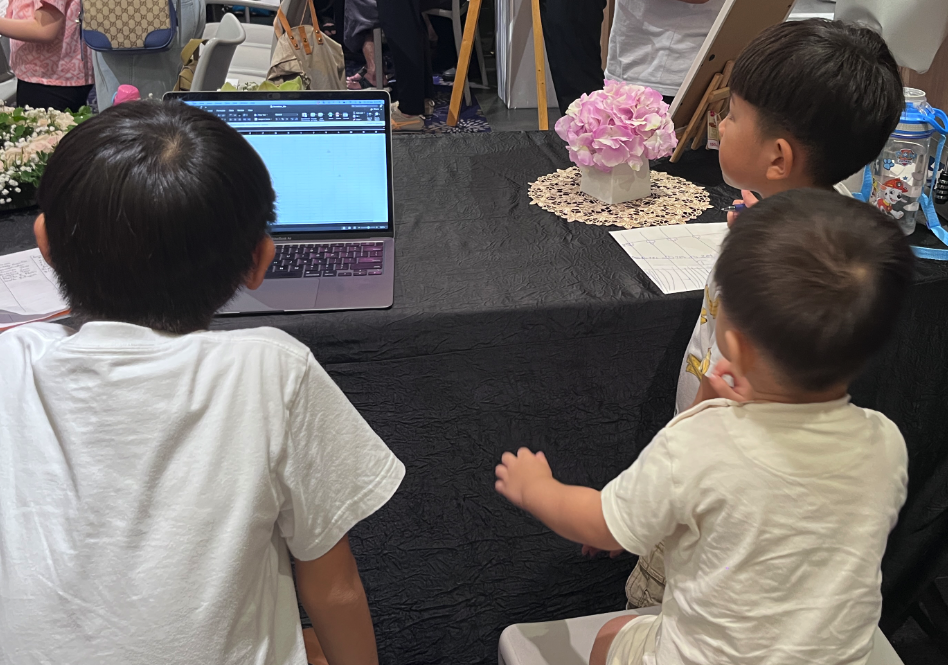

My brother and nephews helped to collect and record down condolence money. This was to cover the costs for the wake, funeral, and the spreading of ashes ceremony, which amounted to about S$13,000.

My three very responsible nephews manning the front desk at the funeral parlour.

My three very responsible nephews manning the front desk at the funeral parlour.

The cost of a funeral

S$13,000 was quite a sum to spend for someone who wasn't around to attend it (at least based on my own religious beliefs).

According to SingSaver, the cost of a funeral starts from S$3,800 to over S$10,000 for ones that span about three days. How much it costs depends on various factors like the duration of the funeral, the type of coffin, and how lavish you want the ceremony to be.

Singapore's competition watchdog recently admonished (gently) funeral service providers for not being transparent about their products, with the Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (CCCS) calling for best practices to highlight to consumers that package prices could be subject to change if additional items are procured.

A staff member from Singapore Indian Casket told Mothership that while some ceremonies they hold can cost about S$4,000, some can go for double that with more expensive coffins and more flowers and garlands.

According to the CCCS's Market Study on Funeral Services Industry, the reported spending of respondents who had experience making at-need funeral arrangements from 2018 to 2020 ranged from S$1,000 to more than S$9,000, with the median respondent paying between S$5,000 and S$8,999.

Even though pet funerals aren't as lavish, they can cost between S$100 to about S$700, depending on the size of the pet.

Odey's creation service cost us about S$400 — the price of sending off a small Jack Russell.

Yup, it's quite a lot of money for someone who's no longer around.

For the living, not the dead

I can imagine — if she were around at her funeral — my grandma telling us not to make such a big deal about her death and having a simple dinner at home would have suffice. Odey, on the other hand, would be thrilled that he was the centre of attention.

But I guess funerals are ultimately more for the living than they are for the dead.

For the living, they serve two main purposes.

First, it gathers family and old friends.

At my grandma's funeral, everyone was in attendance.

Relatives from Indonesia, old colleagues, in-laws and army mates of my dad, and others who had such a distant relationship from my family that I gave up trying to understand who they were, all expressed their condolences.

Beyond the refreshing conversations with unfamiliar faces, what I enjoyed was the party-like atmosphere, as ironic as it seems — how the kids, grandkids, and great-grandkids were at the funeral parlour together morning to night for three days straight.

Despite the occasion, it almost felt like our Saturday night dinners, Chinese New Year visits, and Christmas parties. Events where the whole family would be gathered.

It was during functions like this that my fondest memories were made: fighting with my cousins about who got the last ampek ampek (an Indonesian dish my grandma made only once every Chinese New Year), dancing to Hi-5 on her television before being forced-fed porridge with broccoli for dinner, and having a Boggle tournament with my grandma.

My grandma, cousin and brother who were big parts of my childhood.

My grandma, cousin and brother who were big parts of my childhood.

Second, it was an opportunity to say a final goodbye.

I fought to hold on to the memories of my grandma. Not only the things we did together, but also how the wrinkles at the corner of her eyes would crease when she smiled, and how she had to hug me and kiss me on each cheek every time before I left her house.

For my buddy Odey, it was how it felt when I carried him, how prickly his fur (which stayed in place no matter how much I tried to mess it up) was and how his coarse tiny paws felt against my palm.

My brother, Odey, and I in December, 2006.

My brother, Odey, and I in December, 2006.

When the staff from the animal cremation services came to pick up Odey's body to bring it to the morgue, I took every chance to hold his paw one last time and stroke the fur on the top of his head.

But when his now 7kg body — thinned out after he lost his appetite over the last week of his life — was stuffed in a body bag and then into a styrofoam box, I felt my chest cramp up and my knees become weak.

I was grateful for the extra time I had when I saw his body again at the Sanctuary Pet Cremation in Kranji.

Unlike that Friday, my eyes weren't as swollen and misty, my mind not as disturbed by the sight of his lifeless body, and I was more prepared to say goodbye.

I brought with me a piece of paper with my goodbyes written in dark red marker, and let it burn with him in the furnace.

For my grandma, I was able to give her a proper send-off at the end of the three-day wake when my brother and I were scheduled to give the final eulogy.

Despite two full days at the funeral parlour and an early morning the day after, we stayed past 3am to write the eulogy. We laughed so hard while recalling old memories while trying our best to be serious — we, the youngest of the grandchildren, by far the naughtiest then and now, were tasked to deliver our grandmother's eulogy.

My grandma, brother and myself.

My grandma, brother and myself.

For one night and one night only, we readied ourselves as stand-up comedians would — we lined our speech with jokes, moments so chaotic we can only laugh at them now, and plotted which relatives we were going to target with their most embarrassing stories. It was going to end the wake with laughter and joy.

But when we delivered it, I was quickly brought to tears. For all our joking, this was our final goodbye to my amazing ma.

I ended the eulogy with this:

"Ma, Winnie the pooh once said this: 'If there ever comes a day when we can’t be together, keep me in your heart. I will stay there forever.' We love you ma, thank you for watching us grow up. You’ll always be in our hearts."

One by one, my family members picked up a flower from a wooden weaved basket and placed it in the coffin. I picked up a white rose and placed it on her hands crossed above her torso.

It's been two months since Odey and my grandma have passed and my heart still aches at the thought I will no longer wake up to Odey sleeping by my bed in the morning, and that my grandma isn't making my favourite home-cooked soups for Saturday dinner.

But I'm glad that I was able to say a final goodbye to both of them. Through their funerals, we celebrated them in the way we knew best — for Odey, by giving him all the attention he deserved, and for my ma, by all coming together on a Saturday. Just like we always have.

Top image from the Kwa family

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.