Firsthand: Community is a new series by Mothership, where we explore the spirit of community in Singapore through in-depth articles and videos.

From Tampines to Tuas, we’ll investigate the untold stories of the different neighbourhoods in Singapore — firsthand.

Warning: This article contains descriptions of body dysmorphia, gender dysphoria, and suicide ideation. Reader discretion is advised.

Shania, 43, has come a long way.

For decades of her life, she struggled with mental health issues.

Shania had always felt that there was something wrong with her body. She just wasn't sure what.

But in 2019, all that began to change. While undergoing mandatory drug rehabilitation at a centre managed by the Singapore Prison Service, she met a transgender woman who was staying in one of the male facilities with her.

“I was like, why are there women in our male facilities?” she told me with a soft laugh.

But amidst the confusion, there was also a moment of resonance for Shania.

"When I see them, I see hope," she recalled.

Shania would later learn that while this person lived as a woman, she had been assigned the male sex but had not changed her legal status to that of a female, and was thus placed in a male facility.

Shania was also assigned the male sex at birth, and for many years, had been living as a gay man.

But for some reason, when the woman at the rehabilitation centre asked her if she was gay, she was unsure of how to respond.

This simple question marked the beginning of a difficult journey of self-discovery for Shania.

Shania with a scarf from the clothing brand r y e, which donates profits from their Love+ scarves series to The T Project.

Shania with a scarf from the clothing brand r y e, which donates profits from their Love+ scarves series to The T Project.

Gender dysphoria

Despite having lived as one for most of her life, Shania said she'd struggled with being profiled as a gay man.

At a health screening before full-time National Service, she was told that she was "probably gay". Shania still recalls the awkward conversation that sparked with her mother:

“My mum [asked], ‘Are you sure you’re gay?’ I said, ‘Uhh, mum, I like boys.’”

However, her experiences never felt congruent with the "male" label.

According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — an internationally accepted diagnostic tool for psychological distress and disorders — gender dysphoria refers to the psychological distress that someone feels when their assigned sex at birth and gender identity are misaligned.

Many (but not all) transgender people suffer from gender dysphoria.

"I felt like a woman stuck in a man's body," Shania said. "When I see women getting married to men, I would envy the woman. But I didn't know why."

While Shania had relationships with other men, she struggled with physical intimacy.

"I was living abroad in Edinburgh for a while, and I was married to a man," she recalled. "But when we tried to be intimate, it failed miserably."

"My husband asked me, 'Aren't you happy that we're married?' And deep inside, I knew I wasn't happy, because there was something wrong with my body.

I looked at him and I thought: 'Did I lie to you? Did I lie to myself?'"

She even recalled that many of her gay friends envied her for what seemed to be a "perfect gay lifestyle" — being legally married and living in an accepting environment.

"My identity had always been labelled as a gay person," Shania said. "I didn't know how to manoeuvre out of it."

Little did they know that Shania was quietly suffering from gender dysphoria.

Like most other forms of psychological distress, gender dysphoria can be treated.

But for decades of her life, Shania did not know how to identify her experience as gender dysphoria, much less seek help.

Falling to drugs

After her marriage fell apart, and Shania returned to Singapore.

Growing more desperate with no way out, she began to harbour thoughts of ending her own life. She turned to drug consumption to cope with the pain.

In 2019, she was arrested for the first time and sent to a drug rehabilitation centre. That was also the first time she met other transgender women.

"When I saw them, I saw myself," she said gently. "I felt so connected."

When she was released from the rehabilitation centre, however, things took another downward turn.

Despite the hope that Shania saw, she had little knowledge on what her next steps could be.

She fell back into the all-too-familiar path of a depressive cycle; her suicidal thoughts returned; she fell back into using drugs to cope.

She was arrested again in 2020. But the circumstances were different from before.

This time, she was referred to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed her with gender dysphoria.

She also saw an endocrinologist — a medical professional who specialises in health conditions relating to problems with the body's hormones — who administered a blood test.

Her testosterone levels were found to be abnormally low amongst the average male person, while her estrogen levels were higher than average, and her body was found to be suitable for hormone replacement therapy.

Medical intervention

As part of her rehabilitation programme, Shania was given mandatory medical treatment for gender dysphoria.

Her endocrinologist administered hormone replacement therapy, which would increase the level of estrogen in her body.

From there, a world of possibilities stretched out in front of Shania.

"I started to see hope," she said. "I couldn't fathom the fact that I was actually, seriously, a trans woman."

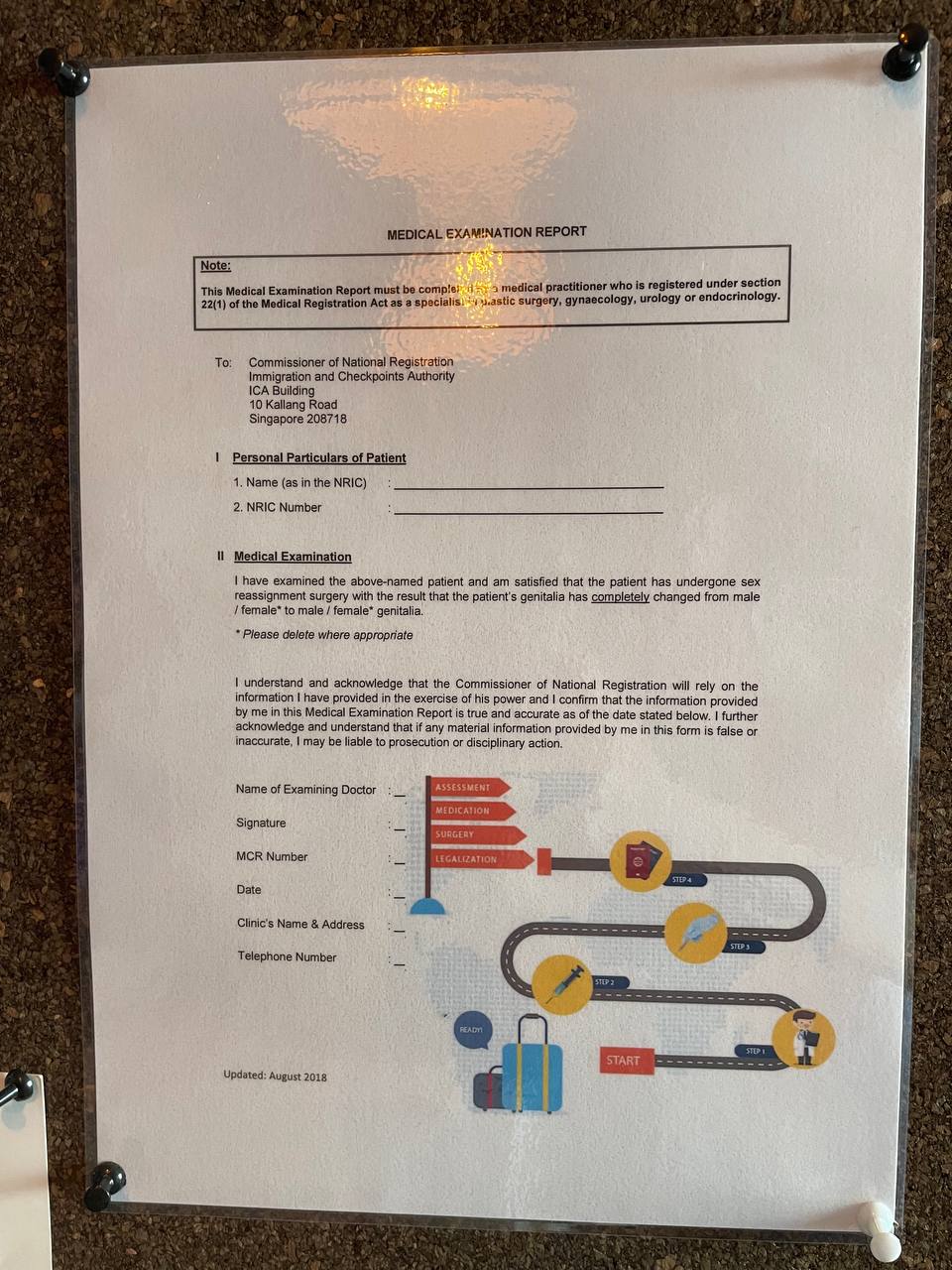

After a transgender person undergoes gender confirmation surgery, they are allowed to legally change their sex on official documents, such as on their NRIC.

A copy of a medical examination form pinned up in the Alicia Community Centre. Medical professionals can use the form to certify that a transgender person has fully undergone sex reassignment procedures.

A copy of a medical examination form pinned up in the Alicia Community Centre. Medical professionals can use the form to certify that a transgender person has fully undergone sex reassignment procedures.

The medical treatment was a huge success for Shania.

She no longer had to rely on drugs to cope with her depressive states, and was soon able to start working again.

"I couldn't go back to that life. I had to live on drugs in that life," Shania reflected. "When I was treated with HRT and gender confirmation surgery, I felt so alive in my body."

"It was very transformational, because that was when I started to feel so aligned with my body.

I felt good — like, wow! I didn't feel embarrassed, I didn't feel shy about my body, and I felt very connected."

The T Project

Although Shania finally received medical treatment, there were still some hurdles to overcome.

Her mother had passed away in 2019, and her father ended up remarrying, sold the family home, and moved abroad — all while she was in prison.

While her father left her a sum of money, she was hardly in the state of mind to be making such a big decision as buying a home.

When she was arrested for a second time — for falling into drugs again — she was allowed to serve part of her sentence on house arrest. But there was no home for her to return to.

As such, in 2021, Shania was referred to The T Project, a homeless shelter in Bukit Merah.

Askre (left) is the shelter manager at The T Project. G Pereira (right) is a social worker who has supported Shania through her transition journey. Photo courtesy of Shania.

Askre (left) is the shelter manager at The T Project. G Pereira (right) is a social worker who has supported Shania through her transition journey. Photo courtesy of Shania.

Shania was not the only transgender person in such a situation.

Many transgender people face homelessness for a variety of different reasons, such as rejection from their family members and difficulty finding employment.

To combat this, The T Project was founded in 2014 by June Chua and Alicia Chua, both transgender women.

The T Project works together with hospitals, social workers, and government organisations to provide temporary shelter and support for transgender individuals through mental health and financial issues.

June also worked closely with Shania to support her through her transition.

In particular, there was one important adjustment Shania needed to make before she could fully transition to womanhood.

"I hadn't really explored wearing female clothes," she said. "And I love makeup, but I was always too shy about it."

When Shania entered the shelter, June introduced her to a community of transgender people. They showed Shania the ropes and helped her socially transition as a woman.

"It's a very special place," Shania said. "The T Project opened so many doors for me."

"They help people living with gender dysphoria. But at the same time, they are also welcoming to people who are ex-offenders and who need a place to stay.

So I went through this journey with them, and for me, it is a very beautiful thing."

Besides the homeless shelter, The T Project also manages the Alicia Community Centre, which is open to the public.

When I paid the centre a visit, Shania generously showed me around, along with The T Project shelter's manager, Daniel Askre.

Decorated with warm, calming colours, I immediately felt a sense of homeliness as I walked around the centre with them.

The Alicia Community Centre houses an event space, a counselling centre, and a library filled with literature written by or featuring transgender individuals.

The Alicia Community Centre's library, filled with literature written by or featuring transgender individuals.

The Alicia Community Centre's library, filled with literature written by or featuring transgender individuals.

The counselling centre at the Alicia Community Centre.

The counselling centre at the Alicia Community Centre.

The centre also features a transgender history museum, with artefacts donated by people from the transgender community.

Shania poses beside a shelf full of artefacts donated by transgender people.

Shania poses beside a shelf full of artefacts donated by transgender people.

A diverse community

At The T Project, Shania also realised that the transgender community was more diverse than she thought.

Some transgender people don't experience significant distress, and simply feel that their gender does not align with their assigned sex at birth.

In other words, not all transgender people experience gender dysphoria, and not all people who suffer from gender dysphoria are transgender.

Shania recalled some moments of misunderstanding because of this diversity within the community.

"A lot of trans women, or trans women in my faith, will come to talk to me," Shania said, a practising Muslim. "They will ask me, 'You want to do surgery is it? Don't do it—you'll regret one!'"

Such comments increased her feelings of dysphoria and gave her feelings of self-doubt.

As Shania learned, transgender individuals who do not experience dysphoria might eventually come to regret undergoing gender confirmation surgery.

Fortunately, The T Project also helped to connect Shania with other transgender women who experiences similar to hers.

"They told me not to listen to other people. Other people could do whatever they wanted. But I had to be comfortable with myself," Shania said.

For these women, undergoing surgery is more of a medical necessity than a matter of choice.

As she interacted with different parts of the transgender community, she eventually learned how to manage these differences in perspective. She reflected:

"I've learned to live life with respect and kindness. You don't have to respond to them in a negative manner.

I'm happy that you're happy with your journey. But I'm also happy with my journey."

Changing her name

As part of her social and legal transition, Shania also changed her name to reflect her identity as a woman.

It was a name suggested by a former boyfriend, with, Canadian singer-songwriter Shania Twain as the inspiration.

She pointed out that Shanaya is also an Arabic name that means "God's gift".

"Being a Muslim, I was like, 'God, are you trying to say that you're giving me a gift?'" Shania said with a smile. "You know, the gift of accepting my [gender dysphoria] and getting treated for it."

"Now, I'm actually transitioning to my female self," Shania continued.

But it wasn't always easy for Shania to reconcile her transgender identity with being a Muslim.

"When I first started transitioning, I got questions from friends of my faith," she said.

"Oh, you do this kind of thing, don't you think it's a sin?" she recalls them asking.

Fortunately, The T Project helped to connect Shania with faith community groups, as well as mosques that offer religious counselling for transgender people.

As she met people of her religion who accepted her, Shania started feeling more comfortable with herself and has been reconnecting with her faith.

Doors to kindness

After years of struggling with gender dysphoria, Shania hopes that sharing her story will inspire others in her situation to find hope.

She also hopes to share that gender-affirming healthcare is not just a choice but a form of medical intervention.

"As I told my story from a medical perspective, from my struggles, and from how I received treatment, I realised that people started to see it with compassion, and not with disgust," she explained.

Through all the struggles of her life, there is one value that Shania has held on to.

"I've learned to live life with kindness. You know, why should I go and make things difficult for people?

I believe that when you're kind, a lot more doors to kindness will open for you."

When I heard this, I couldn't help but feel a sense of admiration for Shania.

For a large part of her life, she had been living with gender dysphoria without any medical intervention. She even found herself on the brink of death by suicide, and turned to drugs to cope.

But instead of dwelling on her own pain, and despite her complicated past, her outlook on life was remarkably simple.

She simply wanted to live with a fierce sense of authenticity, and an unwavering sense of kindness.

I was not alone in feeling inspired. Shania's resolve has impacted the people around her, including the workers at The T Project.

"I am constantly learning from my residents," said The T Project founder June Chua. "And the first lesson is always to live your lives authentically."

June has been working with Shania since she first entered the shelter.

She continued:

"Shania is intelligent, articulate and eager to make a positive change in her life. She has proven to The T Project that when (and not if) someone is ready, we can expect magic to happen in their life."

As I looked around the Alicia Community Centre, I wondered what other kinds of magic have touched the visitors of the community centre, and the residents of The T Project's shelter.

If there was one thing I learned from my conversation with Shania, it was the importance of living a life of authenticity and kindness.

The magic will naturally follow.

Have something even more interesting going on in your neighbourhood? One-up us at [email protected].

Firsthand is a new content pillar by Mothership, featuring in-depth stories about people and their issues.

Top photos by Ryan Yeo and courtesy of Shania.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.