The announcement on Jul. 7 that Transport Minister S Iswaran was assisting with a Corrupt Practices Investigations Bureau (CPIB) investigation was a shot of out of the blue for Singaporeans.

The agency did not divulge any information aside from its assurance that it would tackle the investigation with "strong resolve to establish the facts and the truth".

CPIB investigations where a Cabinet minister is involved are exceedingly rare in Singapore.

Prior to this year, the last time CPIB investigated a minister was more than three decades ago, when Lee Kuan Yew was still Prime Minister.

The story of Teh Cheang Wan

The date was January 26, 1987.

Then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew read out a suicide note in Parliament, written by Minister for National Development Teh Cheang Wan.

Teh Cheang Wan. Credit: NAS

Teh Cheang Wan. Credit: NAS

In his note, Teh expressed his sadness for how things had turned out and said it was only honourable for him to "pay the highest penalty" for his mistake.

The mistake?

Lee went on to reveal for the first time that Teh had been the subject of an investigation by CPIB.

Specifically, it was alleged that Teh had received S$500,000 with regard to a land acquisition appeal. He was also alleged to have received another S$500,000 relating to the sale of government land to owners of a hotel.

In total, Teh was said to have received S$1 million, of which he kept S$800,000 and gave S$200,000 to the intermediary who acted as the go-between.

Teh denied the charges.

Credit: NAS

Credit: NAS

And while CPIB had collected enough evidence to hand over the case to the Attorney-General on December 11, 1986, the trial did not proceed because Teh took his life three days later on December 14.

To this date, there is no legal conclusion to the case that convicts Teh of corruption, aside from the evidence that CPIB collected.

But what we do know is that Teh was adamant about not facing trial.

Lee revealed that the minister had offered to pay back the S$800,000 if he did not have to face charges.

Was that indicative of his guilt? Perhaps.

But, a line from his correspondence with Lee points to a more probable concern: Facing the court of public opinion.

"If I am brought to trial, the very process of it which will be painful and long, will certainly be the end of me even if I am found innocent."

Lee referenced this in Parliament when he talked about how the stigma of corruption--one so strong that it "cannot be washed away by serving a prison sentence"--serves as the strongest kind of deterrent.

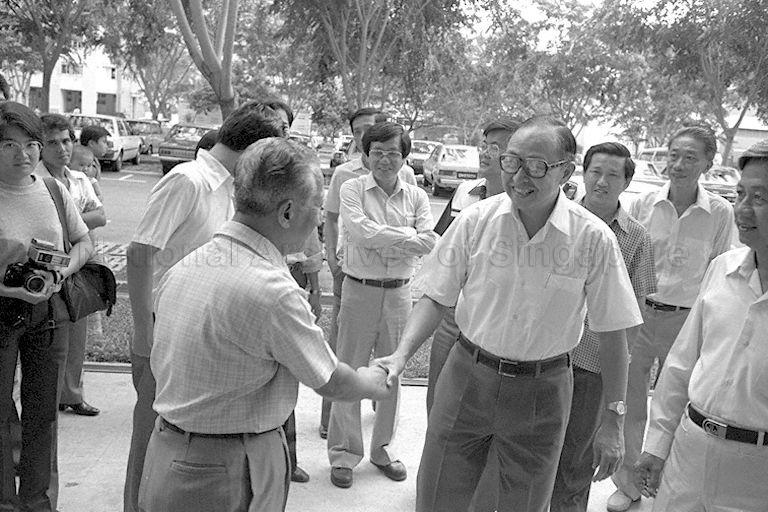

Teh with Lee in 1963. Credit: NAS

Teh with Lee in 1963. Credit: NAS

In Teh's case, perhaps it was the stigma of even having his name associated with corruption that led him to take his life.

In any case, Lee was resolute in his stance against corruption, even when it came to members of his Cabinet.

"There is no way a minister can avoid investigations, and a trial if there is evidence to support one," he said.

"Teh Cheang Wan chose death rather than face a trial on the charges of corruption which the Attorney-General had yet to settle."

"The effectiveness of our system to check and to punish corruption rests, first, on the law against corruption contained in the Prevention of Corruption Act; second, on a vigilant public ready to give information on all suspected corruption; and third, on a CPIB which is scrupulous, thorough, and fearless in its investigations."

Differences between the cases

Prior to this year, the last time a Cabinet minister was involved in a CPIB investigations was more than three decades ago.

Hence, Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) Lawrence Wong explained on Jul. 12 that the Ridout case was very different from the one involving Iswaran.

For the Ridout case, there were questions raised in public, including various allegations online about the two ministers.

CPIB found no wrongdoing, and there was a full accounting of the matter.

The case involving Iswaran was driven by CPIB and there was no public complaint.

Wong also revealed that the CPIB had updated PM Lee Hsien Loong on an investigation it was doing on an unrelated case.

CPIB subsequently updated PM Lee on Jul. 5 and raised the need to interview Iswaran as part of further investigations.

PM Lee then gave his concurrence the next day to open a formal investigation.

Stigma of corruption is still strong today

That stance against corruption is still strong today.

In relation to the CPIB investigation that Iswaran is assisting with, DPM Wong said that the government and the PAP "will not sweep anything under the carpet" in a bid to preserve trust in the government.

But even a whiff of association with potential corruption is enough to bring about significant consequences.

Even though there was no indication about the nature of the case nor the extent of Iswaran's involvement in the present-day CPIB case, analysts are already saying that even the mention of an investigation will severely impact his political standing.

Law professor Eugene Tan told CNA that even if Iswaran is cleared by CPIB and the Attorney-General's Chambers, his party will have to consider whether to field him in the next General Election.

The stigma of an investigation might even affect the PAP's performance in Iswaran's ward, West Coast GRC, which won by a very small margin in the 2020 General Election against a PSP team led by Tan Cheng Bock.

Perhaps it's a necessary burden to bear for being part of a government that prides itself on its incorruptibility.

Related story

Top image: NAS.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.