Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Diyana Amir, a final-year student of NTU’s School of Art, Design and Media, directed and wrote a film called “Paper Planes, Don’t Always Soar”. The film was born out of her personal experience living through her father’s post-traumatic effects after he survived the SQ006 plane crash in 2000.

Diyana shared with Mothership a snippet of the family’s struggles before her dad gradually recovered from his trauma. She hopes to encourage more to speak their hearts out regardless of what they had to go through in their lives.

By Diyana Amir, as told to Zheng Zhangxin.

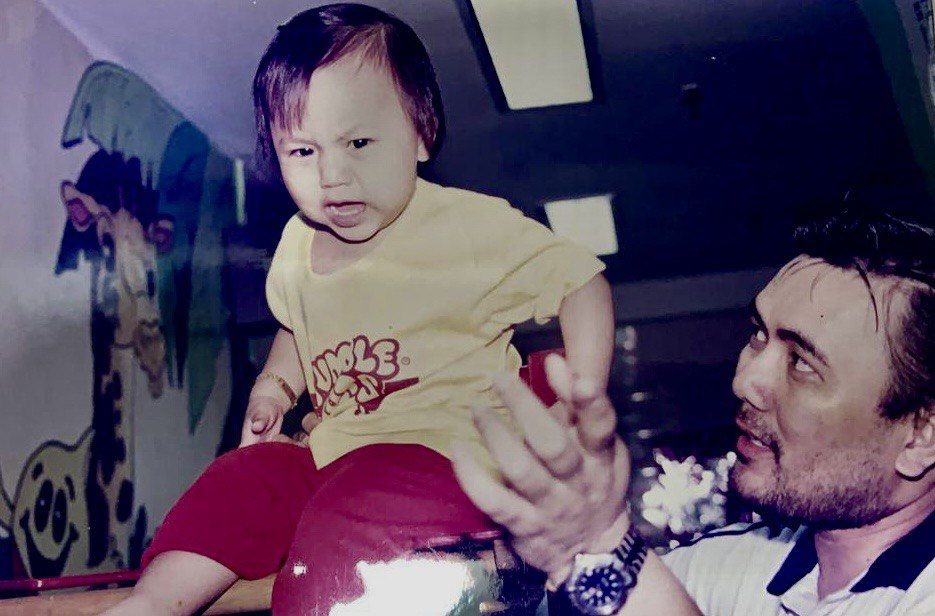

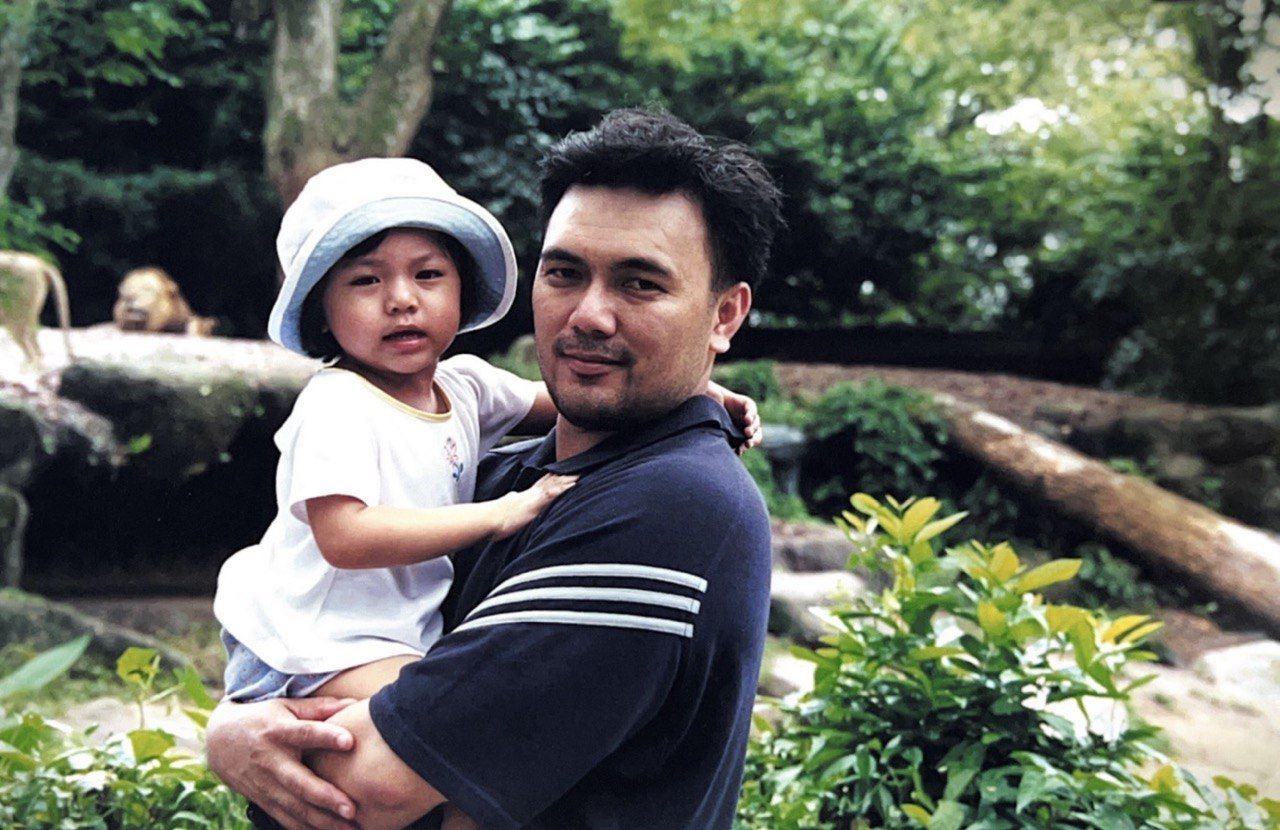

I was about three years old when that happened.

It was midnight, or super early in the morning, when the plane crashed.

So people already picked up on the news when we woke up.

As I was very young, I couldn’t really understand the conversations that took place at home.

Like many kids, what captured my attention were the visual things that happened right in front of me.

For example, my mom and my grandparents were hooked onto the news 24/7.

My dad had not come home for a few days already.

When my mum and I went to get groceries around the neighbourhood or when she sent me to school, a bunch of people were following us.

The community asked us if we’re okay and reporters were waiting outside my door to ask questions and stuff like that.

That’s when I realised: oh, something serious happened.

Getting ready for dad's return after plane crash

I remember my mum being super stressed. Everyone was not themselves.

My grandparents came over to my house to help take care of my baby brother.

My mum was making calls every hour or even like every minute to find out about the updates regarding the plane crash.

It was just chaos basically in the household, that was what really stood out to the five-year-old me.

The plane crash happened in Taipei. As I was young, I was not allowed to fly over but my mum did.

I remember watching the news at home and I saw my dad on the TV.

That’s the first time my grandparents and I saw my dad after learning about the crash.

His arm was in a cast and he had scars on his forehead from the burns.

My grandparents told me I shouldn’t be so forward when my dad came home. I should be more relaxed and to behave myself because he had gone through a very hard time.

It was more like giving me a heads up to what my dad’s mood might be and to calm me down so that I wouldn’t be overly excited, because as a child I was quite talkative.

Through small details, I knew something was off when I saw my dad in-person.

So that’s when I started to figure out what PTSD (post-trauma stress disorder) was at that point.

My dad used to be the one who would always entertain kids while my mum was the strict and serious one.

He was always the one that my brother and I would look for when it came to having fun and like running away from schoolwork.

But upon returning home, he had this very weird change in energy and personality.

The change in her dad and how the family coped with it

He became very sombre and serious, but I just assumed that he was tired or unwell.

I didn’t know what the effects of such an intense trauma could have on him at that time.

I was still looking forward to the usual family days when he would bring us out, but he would just isolate himself in his room instead.

He did not want to socialise anymore.

When my brother was crying, my dad would just do his own things even though he would usually be the one who could calm him down, without losing his temper.

When things triggered him, he would shut the door to signal that he’s not okay.

There was not much communication when he was going through the trauma.

It didn’t help when my mum was also in a very dark place. She was also very tired and stressed.

I remember finding her crying for the first time in a toilet or in a room when she was supposedly alone.

But me being a very curious kid opened the doors and asked her what happened. That was a moment when I realised my mum needed support and help.

Looking back, that moment was memorable as it helped tighten the bond between me and my mum.

It was very difficult. My brother just turned one and so he had no clue about what was going on.

I was really scared whenever my baby brother cried, as that would really trigger my dad and I didn’t want that to happen so I would facilitate playtime for my brother so he wouldn’t cry and anger my dad.

I would pour my own milk even though there was spillage on the table, and I would have to fold my uniform even though it can be crumpled.

I had to put up a brave front as my main goal was to not add more burden onto my parents.

I don’t remember myself being super emotional. It was more like I was very determined to bridge the bond that my family lost.

There were also times when my dad would get nightmares. He would even sleepwalk and reenact something that probably happened to him on the plane, which I didn’t understand at that time.

Sometimes he would approach my brother when he sleepwalked, and carried him as though he was trying to save my brother from something.

And so my mum and I had to stay awake until very late just to make sure everyone was safe.

Because we didn’t know what he would do next.

Such behaviour went on for about a few months, around six months, before the situation improved slowly, progressively.

Turning point

While doing this film, I had to sit down to ask him some questions and what I understood was that he was in this state of denial at first.

I feel the thing that he really remembered was the fact that he was about to lose his life in that second and leave all his family members behind. So there was a sense of guilt and regret of taking up this job that put him in a very high risk.

I also realised that the dad I knew has always been there but he was just lost in the trauma he suffered after the plane crash.

My dad only started to let go of this guilt after attending therapy sessions provided by the airline and accepted that the only way to get the family back together was to recover.

I think that was a turning point for my dad.

He went for therapy sessions regularly and actually listened to the therapists to take medicine.

He would join us watching TV, and eat dinner together.

Even though there was no conversation on the table, his presence itself was telling that things were improving.

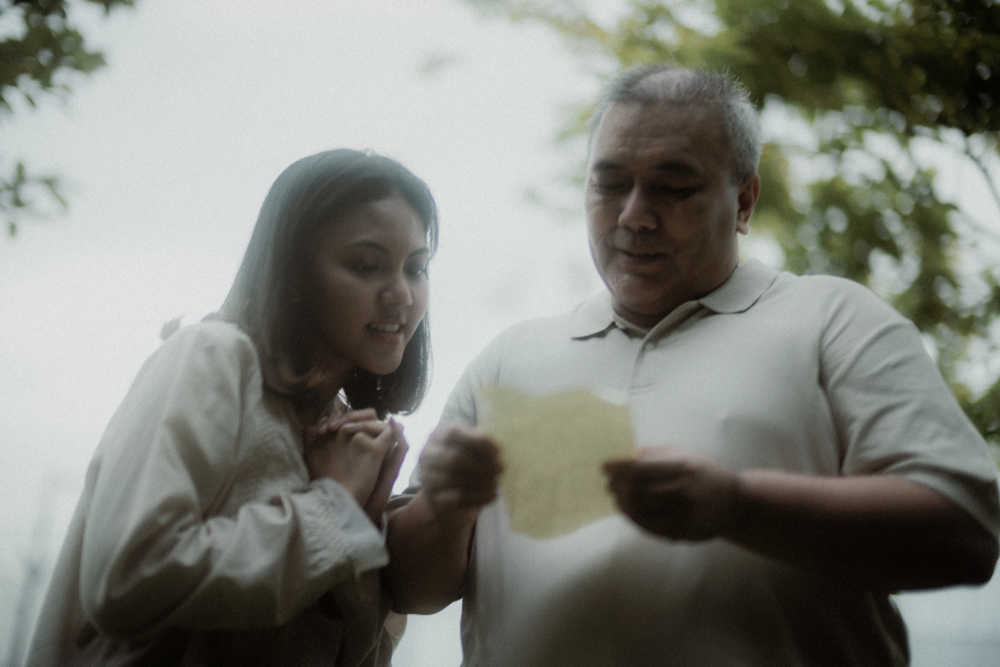

About a year later, he accepted an interview by one of the news outlets. The reporter asked him to share with his kids about the crash.

We were all very awkward because he had never told us in detail what happened, but that day he was willing to do so.

From then on, everything flowed very naturally as we were able to have more conversations with him.

We spoke about schools and had playtimes. It was pretty much back to normal – my mum would prepare breakfast and my dad would send us to school.

Perhaps what made him describe the incident with us back then was something he heard from his therapy session that he remembers till this day, and that is – you just need to let it out in order to move on, instead of just keeping it to yourself.

I feel that’s what I am trying to do by sharing this story with everyone. I also wish to shed light on what families of PTSD victims have to go through. I have lived through that experience, and it is possible to overcome it with a strong and open support system within your daily or loved ones.

Watch:

Diyana and her team are having a private screening for "Paper Planes, Don't Always Soar", & you're invited!

Where: The Matchbox, 30A Kallang Place #05-05, S339213

When: June 24, 2023, from 6:30pm to 9:30pm.

How: You can express your interest via paperplanes_film on Instagram or email [email protected] and they will send you an invitation card.

Find out more: https://www.paperplanesfilm.com

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.