Firsthand is a new content pillar by Mothership, featuring in-depth articles and videos about people in Singapore and their stories.

We'll explore issues that matter by experiencing them for ourselves, gather expert opinions, and hear the perspectives of young Singaporeans, to present the points of view that matter, firsthand.

Gopal Mahey, 39, carries himself with the self-awareness of someone whose mettle has been thoroughly tested.

He seems to have lived a thousand lives. Once an aspiring professional footballer, musician, cabin crew, and drug abuse counsellor, he has also struggled with addiction for most of his life.

Eventually, Gopal was arrested at 33 years old in 2013, after getting caught with drugs and testing positive for methamphetamines. He was taken away from his wife and family after receiving an eight-year prison sentence.

At this time, he was working as a drug abuse counsellor. The irony didn’t escape anyone — he was quickly dubbed the “drug abuse counsellor who took drugs”.

On the other side of the bars than he was used to, his life in prison was bleak, but his family motivated him to better himself as a son, husband, and father. His son was a constant reminder of all the good waiting for him on the outside.

This Father’s Day, we sat down with Gopal to hear about how incarceration and recovery from addiction transformed his worldview and relationship with his son.

Abusing substances for decades: “I was looking for answers and meaning in drugs.”

“I was on substances [from the time I was] 16,” says Gopal.

Gopal tells us his story matter-of-factly, even while furnishing details that would have gotten most people emotional. After all, he has had years for, in his words, “deep reflection” on his circumstances and self-identity.

For Gopal, substances provided an escape from his reality — feeling alone in his childhood, with his parents busy caring for his sickly brother, and a series of career-ending injuries dashing his football dreams.

“I needed to attach to something. That’s where substances came in. I was looking for answers and meaning in drugs.”

As a teenager, he began using substances like cannabis, cigarettes, and alcohol. Working in industries where drugs are a-dime-a-dozen, and accessing drugs at parties around the world as an air steward further fueled his habits.

“It was my crutch. I needed to use [substances] to feel normal. Otherwise, I used to have delirium and tremors and just couldn’t function.”

He would pick up a master’s degree in counselling and find work as a drug abuse counsellor. He took up drug abuse counselling because he “wanted to understand people better, in the hopes of understanding [himself] better.”

An addict himself, he knew the ins and outs of drug addiction intimately.

Laughing at the irony, he recalls how clients would ask, “Gopal, how do you know this stuff, man?”

His boss suggested he respond to such questions by saying he didn't need to try drugs to know their harmful effects.

During this time, the self-described “high-functioning addict” stopped abusing drugs — partly out of guilt and a renewed sense of duty. Instead, he turned to alcohol and tobacco. “I was drinking six cans of beer and smoking two packs of cigarettes a day,” he recalls.

However, when an old friend offered Gopal methamphetamines, the mere fact that he had never tried “ice” was enough to tip him over the edge again. He thought he had enough self-control, but ultimately admitted: “Addiction is not something you can control.”

This led to his eventual arrest in December 2013, just before Gopal and his wife’s first Christmas in their own home — the couple married earlier that year.

It was a rude awakening — only then did his family start to connect the dots on the extent of his substance abuse: “Everybody thought I was okay, just that I was working hard.”

“I was a counsellor. I [was] supposed to have it all together. I wonder how many people really have it all together,” he muses.

His arrest and life in prison

In 2016, court proceedings concluded. At age 33, Gopal received an eight-year prison sentence. “I left all my loved ones behind languishing in pain,” he said.

Gopal had been ready to lose everything, including his wife.

But when she asked him, “Do you think we can get through this together?” he realised that she was prepared to wait faithfully for him.

“I mean, I threw our lives away. But she chose to stick by me,” he says.

Their decision to start a family gave Gopal something to look forward to, and gave his wife “purpose and meaning” while Gopal was gone.

“I think she’s the unsung hero in this whole thing. She showed up for [prison] visits, then went home and managed our home and our son on her own, doing all these things so that I have something to come home to.”

Still, he emphasised that prison "was a tough place to be in”.

“My wife used to come [for visits], and she used to cry. And I wanted to hold her, hug her, but I couldn't.”

It was like imprisonment made time stop, but only for Gopal.

“I saw my dad age. I lost four family members while I was behind bars. It’s like I [was] still in 2016, but everyone has moved on.”

He also had to come to terms with the fact that some people could not, or would not, associate themselves with him any longer.

“[My arrest] brought my addiction out of the shadows. Everybody would now know the worst thing about me.

The ones who remained are the ones who are still with me. But many people walked away; many still do.”

Today, he considers his incarceration as a “blessing in disguise”, and describes finally regaining sobriety as “being born again”.

“Sobriety is a very foreign concept to those struggling with addiction. When I unlearned and freed up the headspace, I realised, ‘This is what sobriety looks like. Gosh, where have I been?’”

He attributes his change in perspective and personal growth to his time in prison, which gave him "the time and opportunity for deep reflection.”

"Today I’m Gopal the inmate, but how do I rise above my present situation?” he recalls asking himself.

Gopal is grateful for the grace that his loved ones gave him through the tough times.

“The forgiveness of my family and my in-laws kept me okay. They were the only ones that really stood by me.”

Building a relationship with his son while in prison

Being in prison limited Gopal’s contact with his son and wife. Gopal could only speak to his family for 30 minutes at a time, never mind hugging or kissing his loved ones.

Naturally, this hindered the bonding between Gopal and his son, who was just five months old when Gopal began his prison term.

After two years of good behaviour, Gopal earned an “open visit”.

For the first time since he entered prison, he could finally meet his family in person.

In the time that Gopal had been away, his son had grown from a baby to a toddler. But when Gopal asked his son if he could carry him, he refused.

That incident helped Gopal harden his resolve to do better. “That was it for me. That was when [I realised] the need for change,” Gopal says resolutely.

Over the course of visits with his wife and son, Gopal eventually arrived at what he considers a turning point, during a tele-visit with his wife and son nearer to his release.

His wife had told him his son would bring the same photo of his father to school every year on Father’s Day.

So when Gopal told his son he was coming home soon, his son asked, “Dad, when you come home, can we take a picture? I want to take a new picture of you to school.”

“At that point, I thought, ‘You’re going to go home and be a good dad. You owe it to the kid,’” recalls Gopal.

Writing “A Wave in the Ocean” for his son

When New Life Stories approached incarcerated fathers to contribute a story for a book, Gopal embraced the opportunity.

Story-writing was part of a programme by non-profit organisation New Life Stories (NLS), which aims to support inmates and their families to prevent intergenerational incarceration.

NLS's in-care programme is conducted by therapists who equip both mothers and fathers with self-awareness and communication skills. The programme is complemented by regular visits to inmates' families by therapists, as well as volunteer befrienders who mentor and read to the children.

The process of writing helped complement Gopal’s own reflections in prison.

“New Life Stories allowed me to look at the intergenerational patterns of fathers in my own home. I want to be very attached. I want to be very involved in my son’s life.”

Although he found it initially challenging to “detach from the prison environment”, Gopal sees that writing the story for his son helped him and other incarcerated parents to intentionally reflect on their own story, to “embrace it and rewrite [their] own narrative[s]”.

“It felt like a healing process of sorts,” he said.

Using the story to start a difficult conversation

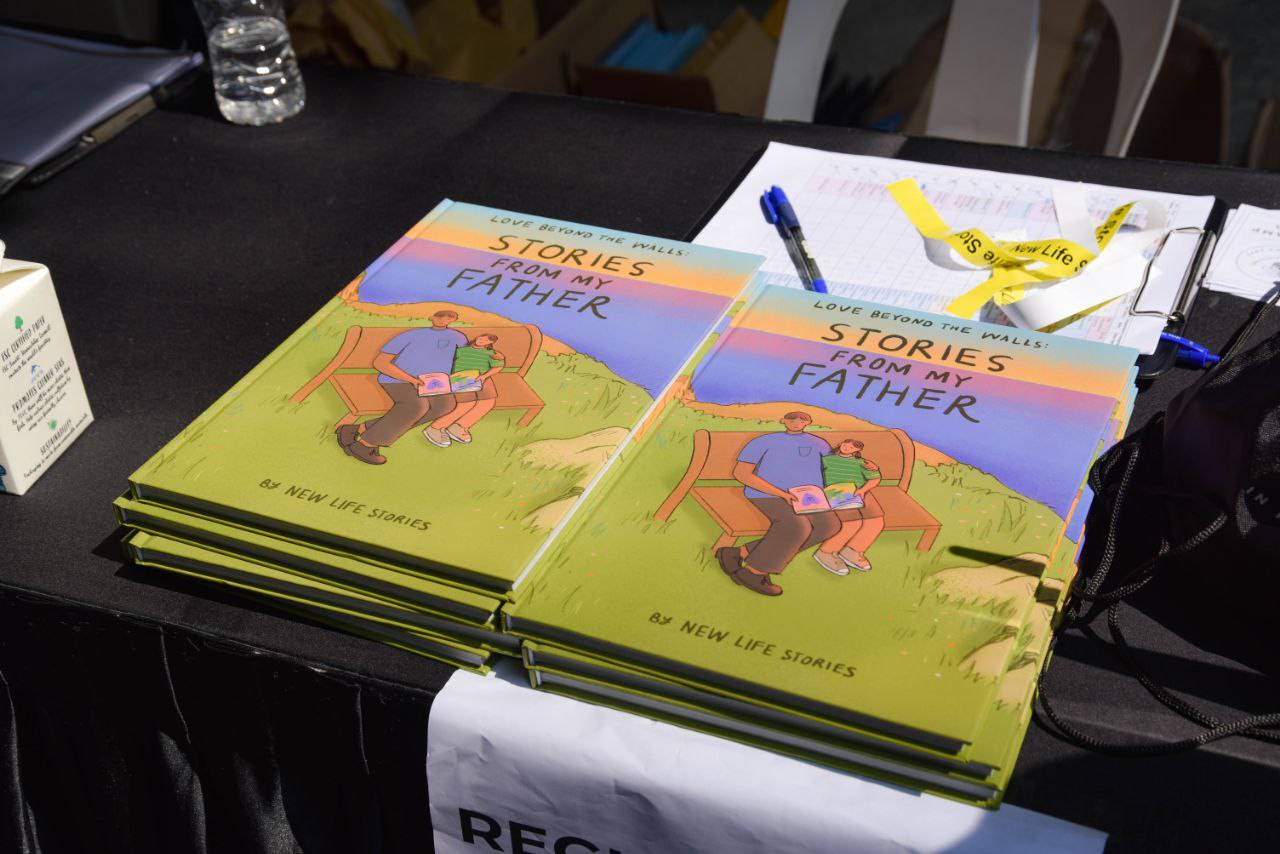

Gopal's story is one of eight in the book “Love Beyond The Walls: Stories From My Father”, which was launched earlier this month at an event on Jun. 4.

Photo by Tellrs Media via New Life Stories' Facebook page.

Photo by Tellrs Media via New Life Stories' Facebook page.

Gopal beams as he shares how his son received the book, proudly sharing it with his grandmother and godfather, saying, "My dad wrote me a story!”

But his son still does not know the full story behind Gopal’s incarceration — only that “Daddy did something wrong, and he had to go to school to learn.”

When Gopal and his wife decide it’s the right time to explain the whole truth to their son, Gopal hopes to use his story to start that conversation.

The story, “A Wave in the Ocean”, is about a baby wave and its father. When the baby wave is too afraid to crash against the shore, his father reassures him by reminding him that he will always be with his baby.

Gopal explains that he decided on this metaphor after meditating on the message he wanted to send his son: “We are more than just one event in our lives”.

“At challenging times, we may think it’s over for us, like the baby wave that’s going to crash against the shore. But when we manage the distractions from the outside world, and we start looking within ourselves, we return to ourselves.”

Gopal plans to refer to the story of how the baby wave felt like everything was going to come crashing down and explain that he had once felt that way when answering for his crimes in court.

The ocean metaphor also carries a message to his son — that “although we may seem small and inconsequential, we are all part of something larger than ourselves.”

Gopal feels this keenly in the area of family — from his family and in-laws, to the New Life Stories volunteer who befriended his son while he served time.

Second chance as an addictions counsellor

Since his release from prison in January 2022, Gopal's life has been imbued with new meaning, from home to work and everything in between.

The sight of trees, and the ability to come home to hug and kiss his pyjama-clad son “feels like a blessing”.

“Everything is like a discovery for me. Things people take for granted have so much substance and meaning for me [now].”

He's also returned to work as a counsellor, working with clients who struggle with various addictions.

Going back to counselling was not Gopal's first choice. He was initially prepared to leave his counselling past behind, and had a plan to join the funeral industry.

He'd even received job offers, but a family member pulled him aside.

“He said, ‘What are you doing? You have a Master’s degree in counselling. Come back to [counselling] and see if you can do something where it all started.’”

It wasn’t an easy decision, but Gopal realised what he learned could perhaps guide others.

His journey of incarceration, recovering from addiction, and dealing with the stigma of being labelled an ex-convict has helped him be more empathetic in his work.

Gopal sees addiction as a mental disease that does not discriminate. After all, Gopal various privileges — of being middle-class, earning a Master’s degree, and having a self-described “intact” family — did not stop him from succumbing to drug abuse.

“I knew of doctors using methamphetamine, man, and lawyers who were using drugs. Who you were didn’t matter. You [were] a substance user. We saw so much of ourselves in each other.”

Reflections on parenting

Gopal acknowledges that as someone who worked as a counsellor and is relatively well-educated, he had an advantage when it came to being receptive to rehabilitation programmes in prison, and in managing his recovery post-release.

But that doesn’t take away from the fact that he has put in hard work to better himself to make amends, earn the respect of his family, and model the way for his son.

Gopal continues to reflect mindfully about the example he is setting for his son.

“Am I the man today that I want my son to become? I imagine the man I envision my son to become — kind, compassionate, resilient, and full of integrity. And then I turn the mirror on myself.”

While he acknowledges that he may not always embody these values, his drive to be a better father to his son helps him to “continually grow and evolve.”

Today, the “drug abuse counsellor who took drugs” has a different perspective on his moniker.

“I carry this label with me every day, and I show up as an ambassador for change. And if I am my own ambassador for change, stigma begins and ends with me.”

His message to incarcerated fathers is similarly empowering.

“In a world that often highlights stories of disgrace and failure, we can choose a different narrative," he says.

"We can harness the power of love, forgiveness, and healing to use the lessons gained from our past to create a better future.”

Those keen to support New Life Stories (NLS) can find out more here. For every S$40 donation, NLS will mail out a copy of “Love Beyond The Walls: Stories From My Father” or "Love Beyond the Walls", a previous edition featuring stories written by mothers.

Top photos by Nigel Chua

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.