Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

PERSPECTIVE: What does it mean to be a Gurkha?

Madan Kumar Gurung, better known as MK Saheb to generations of officers in the Singapore Police Force, comes from a long line of Gurkhas. He was born in Singapore and raised in the mountains of Nepal.

MK Saheb has served Singapore in various positions for over 40 years. When he was 18, he joined the Singapore Prison Service as a Warden before moving to the Singapore Police Force as a Constable at age 21.

In 2005, MK Saheb retired as a Company Commander and Assistant Superintendent of Police. But his work did not stop there. MK Saheb continued to run leadership courses for Singapore Police Force officers.

In his 2022 essay, "A Gurkha's Life", MK Saheb writes about his journey in the Singapore Police Force, his views on leadership and training, and his love for Singapore and Nepal.

MK Saheb's essay was first published in The Birthday Book: Restart. Mothership and The Birthday Collective are in collaboration to share a selection of essays from the 2022 edition of The Birthday Book.

The Birthday Book (which you can buy here) is a collection of essays about Singapore by 57 authors from various walks of life. These essays reflect on the narratives of their lives, that define them as well as Singapore's collective future.

By Madan Kumar Gurung

Some Singaporeans believe the Gurkhas here are mercenaries.

We are not.

Mercenaries are soldiers for hire, with loyalty only to their paymaster.

As Gurkhas, we serve alongside Singaporeans as part of the Gurkha Contingent, a line department of the Singapore Police Force (SPF).

We only serve Singapore. And when we retire from service at age 45, we hang up our boots and do not work for the governments of other countries.

A long line of Gurkhas

I come from a long line of Gurkhas.

My great-great grandfather was in the Sirmoor Rifles, an infantry regiment of the British Indian Army. This later became known as the Gurkha Rifles.

My great-grandfather, grandfather, and father also served as Gurkhas in the British Army, in India, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Brunei.

My grandfather was held in Changi Prison as a prisoner of war in World War Two.

My son is not a Gurkha – he and my daughter both grew up, went to school, and finished O-Levels in Singapore before moving abroad.

They now live and work in the United States, and my wife and I spend many months of the year with them.

I was born in 1959. My father was serving in Singapore at the time, so I was born in the British Military Hospital, which is now Alexandra Hospital.

When I was a small boy, my father was only a corporal. British policy meant my family could not be with him in quarters, so we lived in Nepal.

I lived on a mountain, which isn’t surprising since Nepal is all mountains.

There was nothing else to do but be a sheep herder. A small boy, maybe five years old, with a brother not much older and two big dogs, looking after dozens of sheep on a mountain – it’s quite funny looking back on it.

I did not realise, but it was my first training ground in learning to stay sharp and focused and survive in harsh nature.

Training in harsh environments

My family was allowed to join my father in Singapore when he attained a higher rank in the British Army. I spent several years growing up in Singapore, until my father retired in 1971 and we returned to Nepal.

When I was 18, I tried to join my father’s unit but was not selected.

I was told instead to join a unit of Gurkhas in the Singapore Prisons Service.

I served as a Warder until 1981, when the Prisons and Police Gurkha units were amalgamated under the command of Colonel Bruce Mackenzie Niven and placed under the Police.

I became a Constable instead.

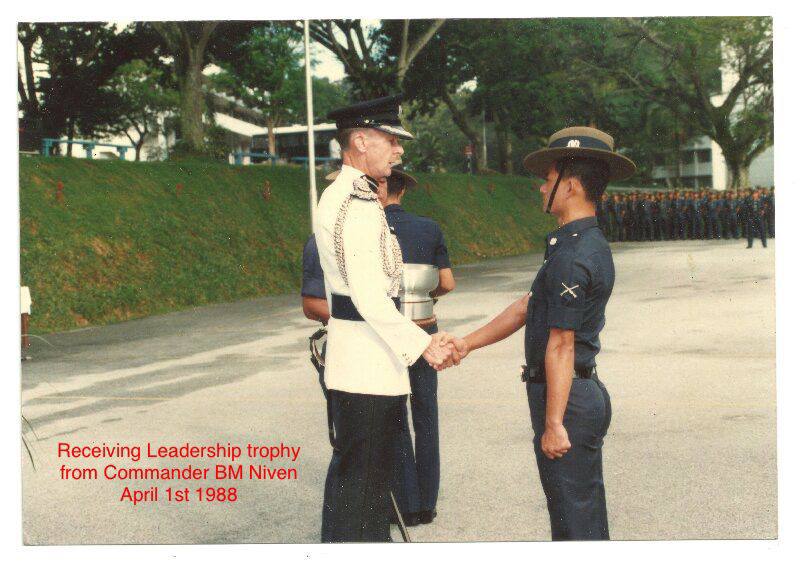

Receiving the Leadership trophy in 1988, having been selected from a contingent of 1600 Gurkhas. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

Receiving the Leadership trophy in 1988, having been selected from a contingent of 1600 Gurkhas. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

A promotion ceremony from Staff Sergeant to Inspector (express scheme) of the Gurkha Contingent in 1994. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

A promotion ceremony from Staff Sergeant to Inspector (express scheme) of the Gurkha Contingent in 1994. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

I retired from service in 2005 as a Company Commander and Assistant Superintendent of Police. My father retired as a Captain, so we actually retired at the closest possible thing to an equivalent rank between the army and police.

After retirement, the SPF hired me as a leadership consultant, a position I kept until December 2021.

I will not say too much about my time in uniform, except that I was blessed with many opportunities to see the world and learn from real, hard experience.

I’ve trained in jungles in Belize, deserts in Australia, mountains in Britain – I was fortunate to be a part of SPF’s contingent in Iraq in 2003.

Leading company level jungle, field firing, land and sea adventure, survival, and more exercises in Belize, Central America for three months in 2001. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

Leading company level jungle, field firing, land and sea adventure, survival, and more exercises in Belize, Central America for three months in 2001. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

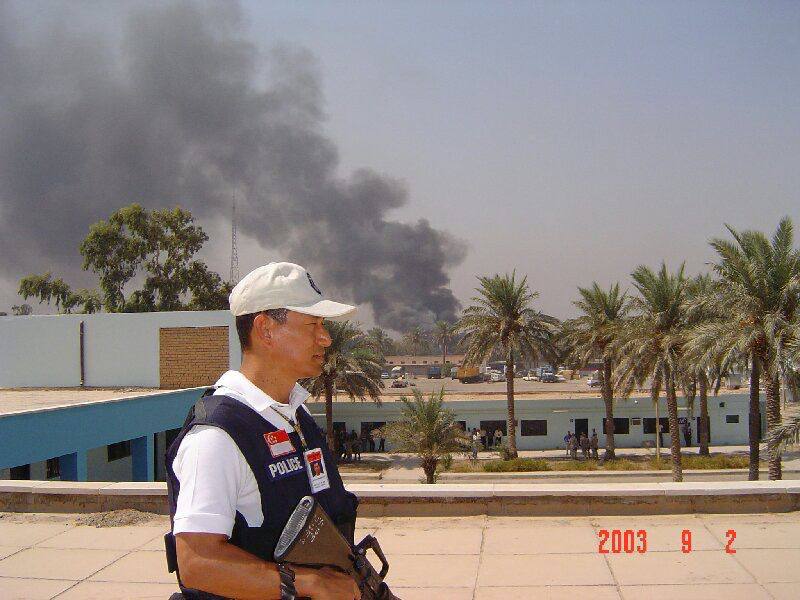

Operation "Arabian Night" at Baghdad, Iraq in 2003. Assisting as a security commander and Chief Instructor with the Singapore contingent from the Singapore Police Force. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

Operation "Arabian Night" at Baghdad, Iraq in 2003. Assisting as a security commander and Chief Instructor with the Singapore contingent from the Singapore Police Force. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

These were all environments where our senses – sight, smell, hearing, touch, taste, and most importantly, common sense – could be the difference between life and death. If something seems wrong, your senses will urge you to investigate.

I always emphasise keeping your senses razor-sharp in both training and operations — sights and sounds can be detected from miles away.

Developing your own style of leadership

But this is all behind me now. My enduring passion is training.

For over 15 years, until 2021, I helped run the Leadership Module in the training course for Senior Officers in the SPF.

I tried to create conditions to show my trainees different styles of leadership and conducting operations. I have reasonable exposure and hard-earned experience, but how could I transmit that to trainees?

Leading Thai senior officers on a Leadership Training course in Thailand in 2003. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

Leading Thai senior officers on a Leadership Training course in Thailand in 2003. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

People rarely learn leadership from a course, but the point of the course is to show you different ways and help you develop your own style and skills for leadership, to give you the confidence that comes from overcoming adversity. You learn to inspire confidence so people will follow you, even in the valley of the shadow of death.

This is why, and my former trainees know this and maybe curse me for it, I was always a bit of a rascal when conducting training. I liked to be outside the book, because if you only stay within the book there will be nothing interesting and there’s no space for imagination.

I used to tell trainees, “Don’t talk to me about safety. I will be very irritated if you do that”.

Of course, I thought about their safety all the time, and everything we did was planned, recce-d, and rehearsed to prevent major safety breaches, but I wanted trainees to focus on seizing opportunities and pushing themselves to their limit, not worry about safety.

It was my job to worry – it was their job to learn. I wanted them to do things their own way, to be rougher, tougher, harder, quicker, wiser and better human beings, not just safe ones.

Moving forward and looking back

I miss doing training, being in the field, and being with my men. Part of me thinks I can do another five years.

I will not be that fast, but I have a lot to impart. That is the core of moving forward. Whatever experience you gain, you have to pass it on.

Maybe one day I will form an institute in Nepal to instill fundamental skills in character building, dealing with adversity, and appreciating situations. But I will focus on Nepalese and Singaporeans, because these are the people I care about.

And of course, it must be in the mountains. There’s something magical and mystical about mountains — I don’t know if it’s spiritual or if the lack of oxygen makes us just a little bit drunk, but officers always seem happier in the mountains.

Maybe it’s all the rum we drink to keep warm.

I’m also happier in the mountains, in nature, even after being born in Singapore and living here for 43 years. I always preferred MacRitchie and Bukit Timah to Orchard Road.

And if I can continue to do something for Singapore, then all the better.

I will never forget what the SPF has done for me, and I will always want to do something for the SPF. After all, Singapore is always near and dear to my heart.

Casual event at the office after farewell from Training Command in November 2021, after having served 15 years as a consultant to the Leadership and Tactical Wing. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

Casual event at the office after farewell from Training Command in November 2021, after having served 15 years as a consultant to the Leadership and Tactical Wing. Photo courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung.

Top photos courtesy of Madan Kumar Gurung

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.