Follow us on Telegram for the latest updates: https://t.me/mothershipsg

Prior to the interview, I receive a text. It's a message from a medical social worker I've been corresponding with.

"Wanted to let you know that the mother will likely cry quite a lot as she is sharing her story," she writes. "Just preparing you mentally in advance."

It's not entirely a surprise. The mother in question, 37-year-old Nilar Aye, has had a rough couple of months.

Just over a year ago, her long-awaited firstborn Esther was born premature — and in a matter of days, diagnosed with a genetic condition that renders the simple act of breathing a struggle.

Meeting Esther

I meet baby Esther in her home, a rented bedroom in Aljunied.

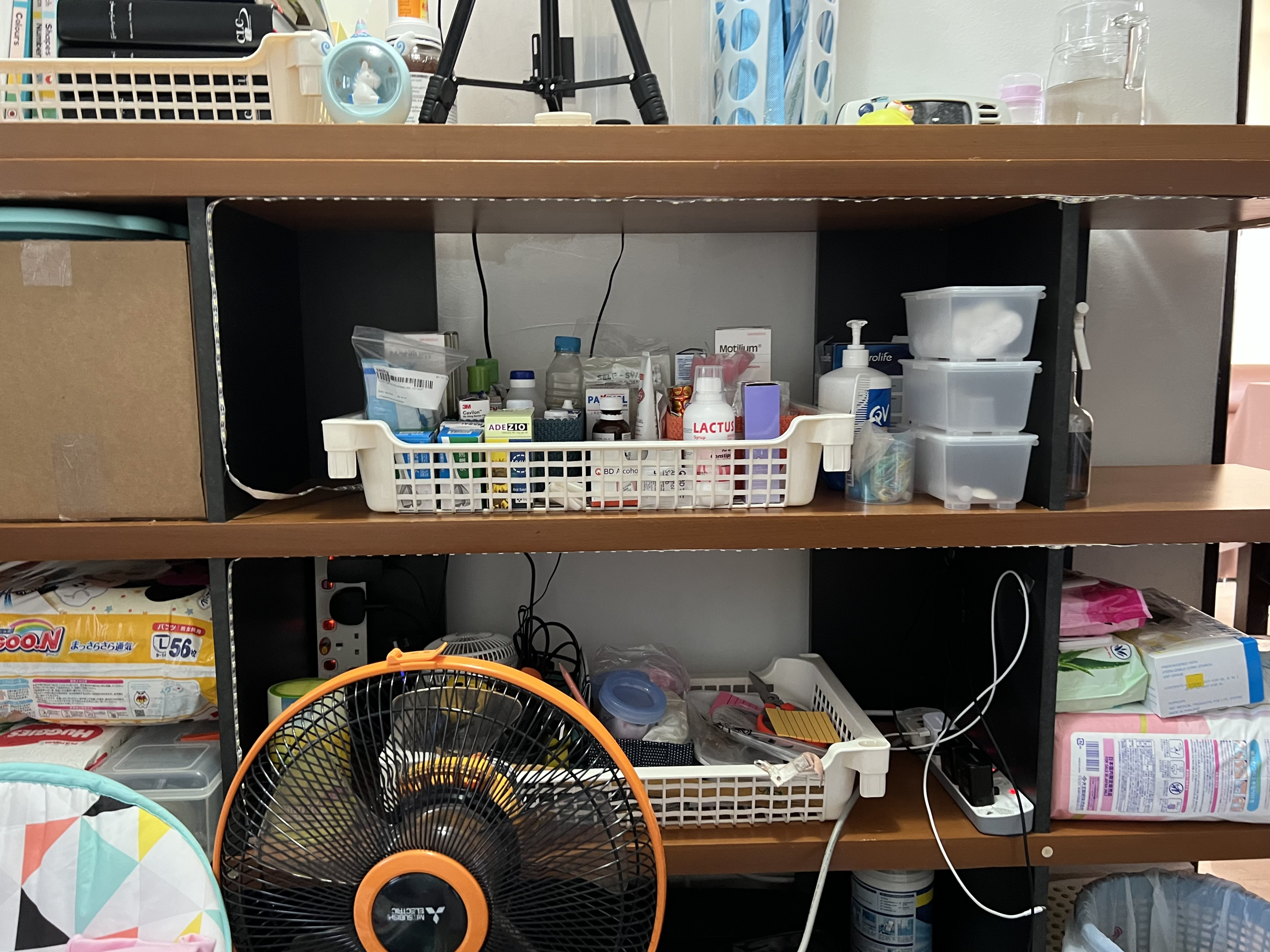

Most of the available space is taken up by bulky machinery and rows of medical equipment. "This is an oxygen concentrator and a ventilator," Nilar tells me as she struggles to tug a ventilator mask over a reluctant Esther's head.

When she was first discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), she needed the mask at all times, and would struggle to breathe even when they removed the mask for a bath.

But these days, she's much better, and mostly just needs it when she sleeps — "because her oxygen will drop," Nilar explains.

The 14-month-old was born with a genetic condition that affects her jaw, tongue, and upper airway, leaving her unable to feed and breathe properly.

Because of the condition's rarity and complexity, her future is unclear. She might learn to walk, talk, and feed. Or she might not.

It all depends on how she responds to treatment. For now, it's too soon to tell; a BMJ study reports that mortality and morbidity for children with Pierre-Robin sequence tapers off after infancy, a stage that Esther is not quite done with yet.

It's hard to reconcile that with the baby in front of me. Chubby-cheeked and insatiably curious, she doesn't take her eyes off me, even after her mum fastens the ventilator mask to her face. Mask aside, she seems like any other baby.

"She likes people. She's very sociable," Nilar explains.

Later, as she demonstrates Esther's daily physiotherapy exercises — an exhausting, painful, but necessary affair — she placates the baby with a YouTube video.

"She likes this cartoon," she tells me. I try to pay attention to the cheerful music, instead of Esther's pained whines, and the endless wheezing of the ventilator machine.

Persisting through uncertainty

Despite the uncertainty, Nilar and her husband, Thet Paing Tun, are persistent and hopeful.

After Esther was born, Nilar quit her job as an assistant in a coffeeshop and has since been looking after her baby full-time.

Meanwhile, her husband takes on extra shifts at his job to pay for Esther's treatment.

Things have gotten easier since she was discharged. At the start, when Esther was still in the NICU, the couple lived in constant fear.

"My husband couldn't eat. And he knew that I didn't like to see him cry, so he would go into the small room, close the door, and cry," Nilar tells me.

"Then he'd come back and [act like] he's okay. But I could see from his eyes, you know?"

Each day is a little easier, with a little less fear as Esther grows stronger — in no small part because of Nilar's own determination.

Her mornings begin early, at 3:30am. It's a flurry of activity all the way into the night: tube feeding, administering medication, and hours and hours of physiotherapy.

The physiotherapy is painful for both mother and daughter — physically for the latter, and emotionally for the former — but it works. "Now she's stronger. Very much stronger," Nilar explains, as she guides Esther through the motions: exercises to strengthen her joints and prevent her muscles from stiffening. (Later, Esther grips my finger, and I feel firsthand exactly how strong she is.)

Nilar even harbours hopes of eventually going back to work, once Esther's health is better.

"I like coffeeshops," she tells me. "I like to cook noodles, make coffee. Like auntie auntie like that. But I really enjoyed it."

Bills bills bills

But while Esther's condition has now stabilised, she has a long journey ahead of her. Most immediately, she is due for surgery soon.

Yet, the couple's mounting debt means that they will need to come up with the S$14,000 cost upfront before the surgery can take place.

As Nilar and Paing hail from Myanmar, Esther's unsubsidised seven-month NICU stay cost over S$400,000 — an astronomical amount, given the couple's modest lifestyle.

"Just one day costs S$3,000 plus," Nilar says. "Our salary in one month is not even S$3,000."

Fortunately, they have raised about S$180,000 so far through a crowdfunding platform.

The campaign is still S$280,000 short of its target, but the couple is determined. Paing's boss is helping them with PR applications, which, if approved, will provide a stable home for Esther and hopefully relieve some of the financial strain of her medical needs.

They also receive financial aid and medical supplies through HCA Hospice's "Star Pals" programme — a service dedicated to improving the quality of children with life-threatening or life-limiting conditions — and Paing continues to work as much as he possibly can. (He was supposed to join in for today's interview, Nilar sheepishly tells me, but was called back to work last-minute.)

Meanwhile, the small family lives simply. Their rented bedroom contains few luxuries — a projector here, an iPad there — and the rest of the space is crammed with medical and baby supplies.

And Nilar does everything she can. From symptom management to breastfeeding — something which she had to do, as special formula proved too expensive — she does everything carefully. Without complaint.

At one point, she was so stressed that she ended up pumping only blood, Nilar said.

"And even though my husband couldn't eat, he always cooked a lot. He said, 'you eat, you eat, you have to make a lot of milk'.

Luckily, it was always just enough for her."

Miracle baby

But all of it is worth it for their miracle baby.

"Around [the size of] the medicine bottle," Nilar said, describing Esther's size at birth.

Her prematurity also meant that her lungs weren't fully developed. After the first two to three minutes of her life, she stopped breathing.

Esther was promptly whisked away to the NICU, where she would stay for the next seven months.

"After I gave birth, I waited for my child," Nilar tells me. "But nobody came to give me my baby. I sat down and waited, waited, waited for my baby.

"I asked the nurse, 'where's my baby?' She went to check, and said that my baby was in the NICU...she said that maybe tomorrow I could go and meet my baby.

But when I finally met my baby, I saw so many wires...a lot of tubes in her mouth, a lot of needles in her body....I was so scared. I just kept crying crying crying, until the doctors and social workers asked me to rest in the other room."

The next few months were touch-and-go. Nilar would pump endlessly and send the milk to the NICU, unable to do anything but wait.

Her husband had a similarly tough schedule — he'd go to the NICU before and after work to see his daughter and pray for her, returning home only to cook, do the housework, and sleep for two to three hours.

The turning point came when Esther was around seven months old. The doctors had twice tried to extubate her, but both attempts failed. She couldn't go on living like this, they said — relying on the mechanical ventilator for each breath, unable to ever leave the hospital.

"So the doctor gave her a last chance. He said, if she cannot breathe when we take out [the breathing tube], and her condition goes down...then we'll let her go."

The day of the procedure, the couple prepared a pretty sundress for her daughter. "In our country, when people are leaving, we will dress them nicely," she explains.

They turned up at the hospital after a night of ceaseless prayer and steeled themselves for their daughter's death.

"But that day, after they removed the breathing tube...she breathed, on her own," Nilar says, laughing. Almost incredulous, to this day she can't quite believe her good fortune.

"She breathed on her own until now."

Que sera, sera

Watching mother and daughter, it's almost incredible. In some ways, they seem so ordinary: Esther babbling away underneath her mask, Nilar anticipating every need, reaching out instinctively with a hug or a wet wipe.

Yet it's clear that Nilar relishes every single moment. Even as Esther gets better, her future is a mystery. Unlike other mums, Nilar will never be able to make elaborate plans on things like tuition classes and CCAs. She will never fall asleep with the full confidence that her child will wake up okay.

In all honesty, she will likely never know okay again, at least not for a long time.

But she has her own hopes. She hopes that Esther will grow stronger — that she will learn to walk, talk, and do things on her own. That her bowel movements will be smooth, and her sleep will be sound.

Despite the seeming endlessness of the task ahead of her, Nilar takes every day as it comes. She loves as much as she can, for as long as she can.

Maybe there's a lesson here. In unconditional love, and parenthood not built on anxious ambition but on a simple, steady desire for life.

Or maybe not. Either way, as I write this piece, I feel that simple hope too.

Whatever happens, I really, really hope that Esther lives.

If you would like to contribute to or learn more about Esther's fundraising campaign you can do so here.

Photos via Give.Asia and Mothership

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.