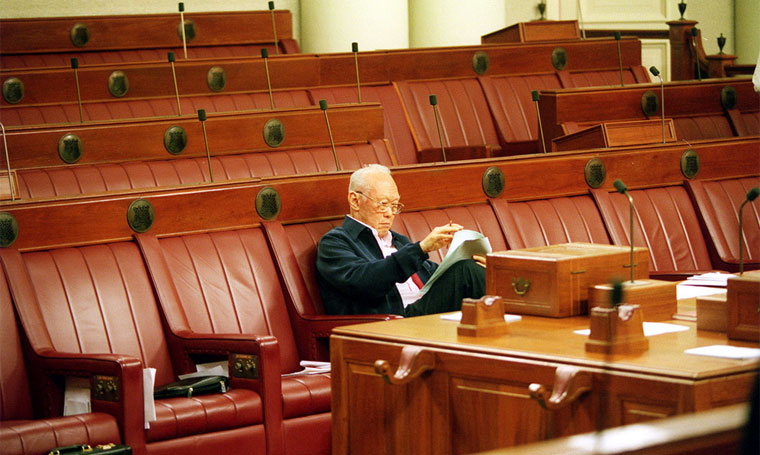

“I thought I should bring the House back to earth,” Lee Kuan Yew, eighty-six, thundered in parliament in 2009. He then delivered a stirring, seemingly extemporaneous defence of Singapore’s unique brand of multiculturalism—where ethnicity is prescribed and integration forced—in response to suggestions that the country was ready for a post-racial future. “Nobody can speak with the knowledge that I have….it is dangerous to allow such highfalutin ideas to go undemolished and mislead Singapore.”

Photo via

Photo via

For Singaporeans, coming fully fifty years after Lee had first led the People’s Action Party (PAP) to a general election victory, it was a stark reminder about the enduring influence and legacy of the country’s first prime minister and founding father.

He is perhaps the only politician in history to lead a country from pre-independence to the “first world”.

Harry Lee Kuan Yew, the first of five children, was born into relative wealth in Singapore on the 16th of September, 1923. His father was a temperamental, third-generation Hakka Chinese who loved to gamble—“a rich man’s son, with little to show for himself.” His mother, a third-generation Hokkien Peranakan, was the hardworking, resourceful steward of the family through testing times, including the Great Depression—when rubber prices plummeted, hurting the family business—and then the Japanese Occupation.

Lee, who would go on to study law at Cambridge, considered those three-and-a-half years under brutal Japanese rule as his most educational. It was then that he nurtured the instincts that would serve him well throughout his life.

With shrewd, canny movements and manoeuvrings—and a good dose of luck—he eluded the Kempeitai, the diabolical Japanese military police that massacred thousands of able-bodied Chinese men in Singapore. Uncertain of his family’s financial future, he blossomed into a businessmen and trader: manufacturing, branding and selling stationery gum, home made from palm oil and tapioca flour, which “looked and smelt like beautiful caramel”; and hoarding and profiteering from any good he could get hold of, in an era of hyperinflation.

In everything he displayed his characteristic pragmatism. Though he despised Japanese rule, he quickly adjusted to life under them, enrolling in a three-month Japanese language course and working as interlocutor and middleman between big Japanese companies and the military on the one side and local suppliers on the other. He would later display the same shape-shifting adaptability, when ditching Fabian socialism for state-led capitalism; pan-Malayan nationalism for Chinese-led multiculturalism; and even his name “Harry”, which had been his anglophilic grandfather’s idea, as he polished his image for the Chinese-speaking masses. Sentimentality was the enemy of survival.

He also learned about wielding power by instilling fear. “Japanese terror and torture settled the argument as to who was in charge,” he says. “And could make people change their behaviour, even their loyalties.” The war’s conclusion also entrenched his belief that the ends always justify the means. The thousands of innocent lives lost in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were worth it, he believed, for without them many more might have died. Individuals always had to be sacrificed for the greater good, whether in Singapore or Tiananmen.

Unlike other twentieth-century political icons, such as Nelson Mandela, Lee never came clean, never made peace with his foes.

Political scientists will dispute his main contribution to Singapore and the world. For in the rich hagiology around him, many myths persist. The most absurd is that he transformed Singapore from a “fishing village” into a modern metropolis. On the contrary, by the 1950s Singapore, one of the jewels in the British Empire, was already a thriving trading port, one of the richest cities in Asia. Though lacking in natural resources, its geographic location was a Godsend. It seems more reasonable to assert that Lee (and his team) did a fabulous job of fomenting Singapore’s well-established competencies, including in trade, transportation and finance.

Observers often praise Lee’s achievements in relation to the supposed backwardness and lethargy of Singapore’s immediate neighbours, such as Indonesia and Malaysia. But these countries are infinitely more complex and diverse than Singapore.

Curiously, few make the more relevant comparison, to Asia’s two other Chinese-majority small states: Hong Kong and Taiwan, which have both achieved a fair bit without anybody like Lee.

Singapore’s small size, far from being a source of weakness, actually meant Lee could adroitly steer Singapore through turbulent economic waters, chopping and changing policies as he pleased, marshalling the entire country’s resources at a whim, ushering in entire new industries while shepherding out old ones. Had he been in charge of a larger, economically heterogenous country, as many of his sycophants wished, his methods would have failed—or at least taken much longer to work.

Photo via

Photo via

What, then, were his main contributions to Singapore? The first was national security. After independence in 1965, Singapore’s sovereignty was not assured. Konfrontasi with Indonesia and the messy separation from Malaysia had scarred Lee. Meanwhile a Communist wave threatened to sweep across South-east Asia. Without the departing British forces, who completed their withdrawal by 1971, Singapore was left with a skeleton military presence. Through a combination of grit, experimentation and his renowned geopolitical acumen—forging an alliance with the Israelis—he built an army from scratch. With the country secure, its economy could flourish.

The second contribution was creating a fairly cohesive national identity stemming from pragmatic traits, such as individual responsibility, hard work, tolerance, incorruptibility and a belief in meritocracy. The third was levelling the economic playing field, partly through the delivery of good, affordable public housing, healthcare and education. Singapore society was much fairer and just in the 1970s-80s than in the 1950s. This was all the more impressive given the prejudiced, race-conscious road Malaysia had embarked on.

The fourth was helping pioneer a unique blend of state-led capitalism that served independent Singapore well in its formative years.

His political philosophies have distinguished him as an original thinker.

One-party rule by elites is efficient as it allows for long-term planning and stability. Conversely, excessive political competition is inefficient because it engenders wasteful short-term politicking. Nevertheless, regular elections are necessary to maintain the Party’s performance legitimacy. The primary role of civil society, the media and the judiciary is nation-building as prescribed by the Party. Western democracy and liberal values are incompatible with Asians.

And leaders must be able to shift gear when the facts change. Consider population policies: in the 1970s, Lee warned Singaporean couples to “Stop at two”; in the 1980s, he incentivised non-graduates to get sterilised and graduates to procreate; in the 1990s, everybody was urged to procreate; and by the 2000s, mass immigration was proffered as the only way to keep the economic engine purring.

In Lee’s instrumentalist, SimCity world, there is a technocratic fix for everything. With the right carrots and sticks in place, a Confucian order will guide society. He believed that only growth could guarantee the survival of this “vulnerable” nation-state.

A motley crew of foreigners revered him. This included African despots and Asian autocrats, all eager to legitimise their rule via the fiction of emulating Singapore. Genuine reformers, from China to Rwanda, cherry-picked particular verses for their use. Western politicians, though aghast at his relativistic views on human rights, nevertheless grew to appreciate many aspects of Singapore, including its business environment, fiscal prudence and complete absence of political gridlock. Visitors marvelled at this oasis of cleanliness and efficiency in the middle of South-east Asia. The world’s largest corporations, meanwhile, sought his consult even in the twilight of his life.

But at what cost has this progress come? Because of his severe allergy to redistribution, Singapore has today become one of the most unequal countries in the world. A rich, elite political class is increasingly out of touch with ordinary people. The homogenous political landscape can no longer satisfy the demands of an increasingly sophisticated electorate. Persistent attempts to crimp free expression have dulled creativity. His brand of paternalism has nurtured a population primed to extrinsic incentives but starved of intrinsic direction. And a national identity forged around pragmatism and money has begun to seem shallow. Is there nothing more to life?

Maybe the truth is that Lee’s dictums and philosophies gradually grew dated. While he was well ahead of his time in the 1960s, by the 1990s he was probably behind.

For instance, his repression of the media had realpolitik justifications in the relatively turbulent post-independence period. But by the 1990s, with a rich, highly-educated and mobile population, it began to act as a drag on Singapore’s knowledge economy, which thrives on the free exchange of information and views.

By then, many of his contemporaries, the only people who could check him, were no longer around. His shadow loomed large over younger politicians, all in awe of the “old man”. Perhaps they yearned to be free of his yoke.

Photo via

Photo via

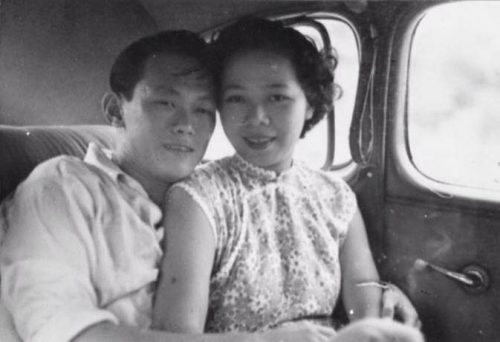

For those who saw Lee as a narcissist, it must have been surprising to see the sobering effect Kwa Geok Choo, his wife, had on him. If Lee is to be remembered as one of history’s greats, then Kwa surely deserves a place in the pantheon of supporting acts. In between pints of stale beer and being called to the Bar in the UK, they found time to get married in Stratford-upon-Avon, keeping it secret from their families for three years.

Humble and gracious, she was the perfect foil. Beneath that demure exterior—neatly-parted hair, elegant cheongsam—motored one of Singapore’s finest minds. The only one, perhaps, to which Lee looked up. While he was busy running the country, she built one of Singapore’s most successful legal practices, Lee & Lee, while raising three children. An astute judge of character, she also served as Lee’s political confidante.

Perhaps Choo—as he called her—was his secret wardrobe to the world of compassion and love that he needed away from his pugnacious public persona. In her final hours, the country wept as Lee sat by her bedside, reading Shakespeare to her, a return to the days of shared idealism, illicit love and char kway teow made from fettucine. When she died, it was as if the universe had been snatched from him. He never truly recovered. That death—inevitable, unsparing death—could cripple Lee showed that in the final reckoning, maybe raw human emotions do have the capacity to overwhelm hard-nosed pragmatism.

Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh is the author of Floating on a Malayan Breeze and co-author of Hard Choices: Challenging the Singapore Consensus. He blogs at sudhirtv.com. Sudhir sits on the advisory board of Project Fisher-men, a social enterprise that owns Mothership.sg

Top photo from RememberingLeeKuanYew website.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook and Twitter to get the latest updates.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.