When recalling Singapore’s physical transformation, the most common changes on people’s minds would probably be the Marina Bay Sands, the city skyline, or the expansion of the MRT network.

However, there are other differences in our landscapes that might have slipped past one’s notice.

From founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew’s vision to transform the tiny island-state into a Garden City by planting 55,000 trees by the end of 1970, to the OneMillionTrees movement today, Singapore has evolved from a Garden City, to a biophilic City in a Garden, and is now transforming into a City in Nature.

Step out of the house anywhere in Singapore, and green is likely to be one of the first colours to greet your eyes.

From tree-lined roads to lush greenery in residential estates, one of Singapore’s attributes is the greenery growing nearly everywhere.

Areas that used to be concretised such as canals and pedestrian pavements are now spruced up with native plants.

Here’s a brief trip down memory lane.

Lush streetscapes

Those in Singapore might have become accustomed to the pinks, yellows and greens of bougainvilleas, Angsana, Yellow Flame and Rain Trees lining the roads and expressways.

This didn’t used to be the case.

Singapore’s roads were not always so lush, and fewer varieties of plants were grown on the roadsides.

Junction of Scotts Road and Orchard Road, taken in 1969. Photo from MITA via National Archives Singapore

Junction of Scotts Road and Orchard Road, taken in 1969. Photo from MITA via National Archives Singapore

Through the government’s continuous efforts since the 1960s, streetscapes in Singapore have been enlivened by a variety of trees and plants, notably the majestic Rain Trees which not only help cool ambient temperatures, but provide shade and shelter for pedestrians, rain or shine.

The country’s extensive streetscape thus forms the “backbone” of our garden city.

Central Expressway. Photo from NParks

Central Expressway. Photo from NParks

You might not have noticed, but the National Parks Board’s (NParks) approach to roadside planting has evolved with the times. The planting palette has shifted over the years from planting trees mostly for shade in the 1970s to providing more colour and variety in the 1980s.

The goal is now for every road to be transformed into a Nature Way in the long term. Nature Ways are routes planted with specific trees and shrubs, creating multi-tiered planting, which mimic natural landscapes and forest structures.

Apart from helping to keep streets cool and comfortable for pedestrians, Nature Ways also help to improve ecological connectivity, allowing dispersers and pollinators like native birds, butterflies, bees to move between green spaces, as well as act as a buffer for sensitive areas like nature reserves.

One example of a Nature Way is Kheam Hock Road, which connects the Botanic Gardens to Lornie Nature Corridor. First unveiled in Nov. 2020, Lornie Nature Corridor is planted with over 100 species of trees and shrubs. Once the plants mature, the route will resemble a forested corridor.

Bedok Nature Way is also one which features more native-dominated plants to link up the green areas at Bedok Reservoir Park and East Coast Park.

There are currently 39 Nature Ways in Singapore, stretching 150km in total. NParks aims to increase this to 300km by 2030.

Bedok Nature Way. Photo from NParks

Bedok Nature Way. Photo from NParks

Lornie Nature Corridor. Photo from NParks.

Lornie Nature Corridor. Photo from NParks.

More parks and park connectors

Singapore might have an extensive network of park connectors now but did you know that the first park connector was only constructed in 1995?

The Kallang Park Connector is the very first in Singapore, and it links two regional parks — Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park and Kallang Riverside Park. Here it is still looking slightly bare:

Photo from MITA via National Archives Singapore

Photo from MITA via National Archives Singapore

And here is what it looks like in recent years:

Photo from NParks, taken in 2015.

Photo from NParks, taken in 2015.

26 years on, people in Singapore can now traverse around the entire island via an extensive Park Connector Network, which includes the 36km Coast-to-Coast Trail.

Some of our parks have also undergone some drastic changes, one of which is the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park.

The Kallang channel was previously a 2.7km-long concrete canal. Together with Bishan Park, which was situated next to the canal, both areas underwent redevelopment in 2009 as part of the Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC Waters) Programme to increase the capacity of the channel and create more recreational space.

Photo from Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl

Photo from Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl

Now, the park boasts a naturalised river surrounded by lush greenery that not only attracts wildlife but also functions as a floodplain. After the redevelopment, the naturalised river's carrying capacity was also increased by 40 per cent.

Not only did the redevelopment provide a new haven for people to relax amidst nature, it boosted the ecological resilience of the area — Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park is now home to a diverse range of flora and fauna, including 66 species of wildflowers and 59 species of birds as of 2016. Not to mention the playful smooth-coated otter.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

Increasingly, other parks and green spaces have also been enhanced with the environment, with local biodiversity as well as public health and wellbeing in mind, such as by constructing nature playgardens for children with natural materials, or using man-made constructions to benefit the environment, like floating wetlands.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

In the case of Jurong Lake Gardens, a portion of the freshwater swamp forest was even restored to form the Rasau Walk, allowing visitors to safely meander through and appreciate the greenery and biodiversity where they could not before.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

Increasing ecological connectivity

As Singapore has developed over the years, its existing forests and green spaces have become more fragmented. It is thus important to ensure the remaining patches of green are connected.

This is especially so for the Bukit Timah and Central Catchment Nature Reserves, as these areas with native tropical rainforests serve as refuges for wildlife and are pools of rich biodiversity.

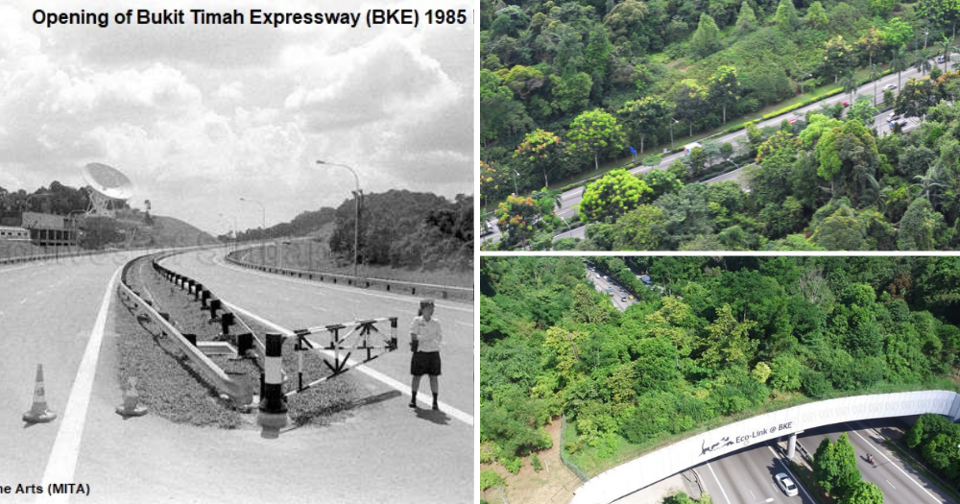

In fact, the forests of the two Reserves used to be linked, up till the Bukit Timah Expressway was built in 1986. The carriageway sliced through the forest, leaving animals stranded on either side. Those that tried to cross would get killed by the heavy traffic.

Photo from NAS

Photo from NAS

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

The idea for a natural bridge to once again reconnect the forests was conceptualised, and in 2011, the construction of the Eco-Link@BKE commenced.

Since then, the Eco-Link@BKE has been put to good use by various critters — camera traps installed along the bridge have captured pangolins, slow lorises, macaques, civets and mousedeer using it for safe passage.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

Greening not just land itself, but buildings too

Ensuring Singapore becomes a City in Nature doesn’t just involve parks and streetscapes. Concrete buildings can be green too.

After the housing crisis in the 1960s, new HDB flats sprung up everywhere, with the priority being getting as many people as possible with affordable roofs over their heads.

HDB flats were mainly concrete blocks, as shown in this picture of the first few flats in Marsiling in 1973.

Photo courtesy of Housing Development Board

Photo courtesy of Housing Development Board

Now, HDBs are being spruced up with vertical greenery as part of an effort to increase skyrise greenery in Singapore’s infrastructure.

This is another method of greening our landscape, considering the country’s limited space and land constraints.

Not only do the buildings look more aesthetically pleasing, skyrise greenery can reduce surface temperatures by up to 3.1 degree Celsius and provide new habitats for important pollinators like

SkyTerrace@Dawson. Photo courtesy of Housing Development Board

SkyTerrace@Dawson. Photo courtesy of Housing Development Board

There have also been initiatives to have a vertical farm on the side of HDB blocks growing vegetables. How convenient!

One good example of the integration between public housing and greenery is Kampung Admiralty, Singapore’s first integrated vertical kampung. It is a one-stop hub with housing for the elderly and co-located facilities for residents of all ages under one roof.

Aside from offering various facilities and shared community spaces for seniors, it boasts lush greenery at its Community Park, an elevated village green where residents can come together to exercise, chat or tend community farms.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

In time to come, Singaporeans can look forward to more of such greenery where they live — NParks aims to have 200 hectares of skyrise greenery by 2030, an increase from the current 120 hectares.

Industrial areas matter too

It isn’t just residential areas getting an upgrade. Industrial areas might remind one of grey buildings and factories, but they’re getting a facelift with some greenery too.

This was Jurong Island in 2018.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

And with more trees being planted...

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

...This is Jurong Island in 2020.

Photo from NParks

Photo from NParks

As part of Singapore’s aim to plant a million more trees by 2030, industrial estates will see close to a threefold increase in the number of trees by 2030, from around 90,000 trees to about 260,000 trees in 2030.

At the same time, there will be about 100 hectares of new green spaces in industrial spaces, including Jurong Island, Jurong Innovation District, Punggol Digital District and Sungei Kadut Eco-District.

The tree planting will be carried out to mimic the structure of plants in a forest, with a tiered planting system with multiple species, as compared to a single row of homogenous trees.

A constant balancing act

These various initiatives to plant trees and set aside land for parks and park connectors were done at no small cost.

In land-scarce Singapore, balancing development and conservation is not an easy feat.

Aside from this tension, we also have to contend with the effects of the close integration of nature in our city through increased human-wildlife interactions.

Despite the numerous benefits green spaces provide, Singapore also needs to accommodate other pressing and necessary land uses such as housing and transport.

One example of this tension is demonstrated in the recent discussion over developmental plans at Clementi and Dover forests; the latter was slated for imminent housing development.

Through public consultations with residents, nature groups, and local biodiversity experts, as well as studies to identify the biodiversity within these forests, a balance was reached.

Half of Dover forest, identified with richer biodiversity, will be retained, while the other half will be developed. New nature trails will be created at Clementi forest to allow nature lovers to safely visit while ensuring the flora is protected even with higher human traffic.

Two new groups -- Friends of Ulu Pandan and Friends of Clementi Forest -- will be created to involve residents and interested volunteers in protecting biodiversity at these two sites.

Ensuring Singapore is liveable for both human and wild residents is why NParks has taken the City in Nature approach in recent years. It is also part of the Singapore Green Plan 2030 to ensure sustainable development for a better and greener future.

In summary, City in Nature aims to conserve and restore natural ecosystems with biophilic designs, strengthen island-wide ecological and recreational connectivity, and inspire communities to co-create and be stewards of nature.

Find out more about our City in Nature here.

If you're interested to know about NParks' various efforts and initiatives, check out their YouTube channel here.

This sponsored article by NParks made the author appreciative of the greenery around her.

Top photo from NAS and NParks

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.