In 2020, Singapore produced 5.88 million tonnes of solid waste. 868,000 tonnes of this is made up of plastic waste.

Although plastic has become one of the most convenient and ubiquitous materials in our daily lives, it is just one of many types of single-use, disposable materials.

Materials like paper and cardboard are also used in packaging, and these two materials contribute to 1.14 million tonnes of the waste generated in 2020.

Considering that we’re in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, and Singapore has just moved back to no dine-in, dabao-ing our food and ordering in have become the go-to options.

This inevitably increases the amount of single-use packaging waste generated during this period. During the 2020 circuit breaker period alone, domestic and trade premises generated about 73,000 tonnes of waste in April, 11 per cent more than the 66,000 tonnes of waste generated in March.

It’s easy to ignore the implications of using this much single-use packaging — after all once it’s in the bin, out of sight, out of mind right?

But let’s confront these implications head on. What happens once you’ve devoured your meal and that takeaway container is disposed of?

Let’s step into the shoes of a takeaway container and find out!

Weighing our trash

Let’s say you’ve dumped your takeaway container in a general trash bin. After all, once contaminated with food grease, most items like styrofoam boxes and plastic cutlery aren’t recyclable anyway.

But if you’re unsure, here’s a nifty graphic of what can and cannot be recycled.

Photo from NEA

Photo from NEA

Once disposed of, your takeaway container will be collected together with all the other and brought to one of the four Waste to Energy (WTE) plants — Tuas Incineration Plant, Senoko Waste to Energy Plant, Tuas South Incineration Plant and Keppel Seghers Tuas Waste-To-Energy Plant.

Refuse collection vehicles are weighed at the weighbridges. Photo from NEA

Refuse collection vehicles are weighed at the weighbridges. Photo from NEA

The full waste collection trucks are driven onto massive weighbridges, and weighed. The waste is then unloaded into waste bunkers and the empty trucks are weighed again. This lets us know how many tonnes of waste are actually being brought in.

A waste collection truck attendant operating the vehicle’s control panel to discharge waste into the bunker at Tuas South Incineration Plant. Photo from NEA

A waste collection truck attendant operating the vehicle’s control panel to discharge waste into the bunker at Tuas South Incineration Plant. Photo from NEA

These waste bunkers are where the trash is stored before incineration. The air in the bunkers is drawn into the incinerators for combustion to prevent odours from escaping, so you don’t need to worry about covering your nose whenever you head to the area.

Waste bunkers at Tuas South Incineration Plant. Photo from NEA

Waste bunkers at Tuas South Incineration Plant. Photo from NEA

Why do we incinerate our trash?

As a land-scarce island city, Singapore does not have the luxury of having massive landfills to simply dump our trash at.

Instead, all the incinerable waste is incinerated. Incinerating our waste reduces its volume by 90 per cent and helps save space at our country’s only operational landfill, Semakau Landfill, located about 8km offshore, south of Singapore.

It is also a cost-effective, more hygienic and human-health friendly solution than piling mounds upon mounds of festering trash somewhere.

Even so, the incinerated ash definitely affects the lifespan of Semakau Landfill. That’s why it is so important to reduce our waste, reuse and recycle as much as possible, to extend our only landfill’s lifespan.

Now back to the plants.

It is time to say farewell to your takeaway container in its original form, as it is about to be dropped into the fiery pits.

At Tuas South Incineration Plant (TSIP), the waste is fed into one of six incinerator units, where temperatures can reach up to 1,000°C.

The Tuas South Incineration Plant. Photo from NEA

The Tuas South Incineration Plant. Photo from NEA

The incineration plants not only turn all that waste into ash, but also generate energy from the process. The heat from the combustion of waste is harnessed to generate superheated steam in boilers, and the steam then drives turbogenerators to produce electricity.

Photo from Tuas South Incineration Plant Brochure

Photo from Tuas South Incineration Plant Brochure

TSIP consumes about 20 per cent of the energy it produces, while the remaining 80 per cent is exported to the national grid. In 2020, the four WTE plants generated about 2180 MWh per day of electricity — this is equivalent to around two per cent of the total electricity demand in Singapore.

After the waste has been fully incinerated, the ash is cooled and quenched in a water bath at the ash extractor. Scrap metal is then separated from the incinerated ash with magnetic separators, and the ash is transported to ash pits via vibrating conveyors.

The ash is then loaded onto trucks via ash cranes and transported to Tuas Marine Transfer Station.

A trip across the sea

This isn’t the end of your takeaway container’s story though.

The trucks containing the takeaway container’s ash make their way over to the Tuas Marine Transfer Station, where it will discharge the ash directly onto special barges.

Ash trucks discharging incineration ash into the barge at the Reception Hall at Tuas Marine Transfer Station. Photo from NEA

Ash trucks discharging incineration ash into the barge at the Reception Hall at Tuas Marine Transfer Station. Photo from NEA

A fully loaded barge is pushed by a tugboat on a 33.3km trip across the sea to Semakau Landfill.

This is what a barge looks like. Check out how large it is in comparison to the tiny worker on the left.

Photo from Tuas Marine Transfer Station brochure

Photo from Tuas Marine Transfer Station brochure

Above the waste compartment of the barge is a hatch cover which, similar to that of a lid on a container, will close to cover the waste material inside the barge to prevent rainwater from entering and fine ash from blowing off during their long voyage.

The ashes of your takeaway container will now spend the next three hours of its life at sea until it reaches Semakau Landfill.

A tugboat pushing a covered barge loaded with incineration ash to Semakau Landfill. Photo from NEA

A tugboat pushing a covered barge loaded with incineration ash to Semakau Landfill. Photo from NEA

More than just a barren island

Semakau Landfill was created as a solution to space running out at Singapore’s last inland dumping ground, at Lorong Halus, in the 1990s.

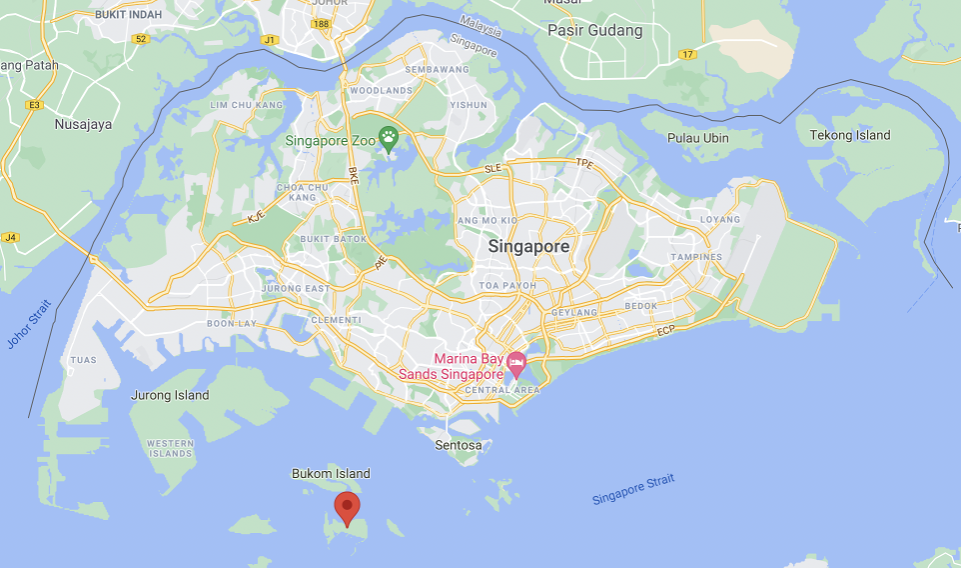

It was formed by enclosing the sea space between two existing smaller islands – Pulau Semakau and Pulau Sakeng, with a seven kilometre perimeter rock bund, creating a 3.5 sqkm offshore landfill.

The bund is lined with impermeable membrane and a layer of marine clay, ensuring that any substances from the ash is contained in the landfill. Semakau Landfill began operations on 1 Apr 1999.

Photo from Google Maps

Photo from Google Maps

Upon arrival at Semakau Landfill, specially designated excavators will unload the waste materials from the barge directly onto dump trucks. This is no simple feat — with the amount of waste we generate, emptying each barge takes about six hours.

An excavator loading incineration ash onto a dump truck at the Transfer Building at Semakau Landfill. Photo from NEA

An excavator loading incineration ash onto a dump truck at the Transfer Building at Semakau Landfill. Photo from NEA

The dump trucks will then transport all that ash to the designated tipping site for landfilling. A 10m wide paved roadway along the top of the perimeter bund, as well as a floating platform, provides access to all sections of the landfill, which is divided into cells.

At each cell, bulldozers and compactors then level and compact the incineration ash, till the landfill area has been filled to ground level. Once a cell is filled, it is covered with a layer of earth.

A dump truck loaded with incineration ash travelling on the Floating Platform at Semakau Landfill. Photo from NEA

A dump truck loaded with incineration ash travelling on the Floating Platform at Semakau Landfill. Photo from NEA

However, Semakau Landfill isn’t the barren, ashy and windswept island you might be imagining.

To clear some misconceptions, this is what Semakau Landfill actually looks like.

No trash in sight, no smell in the air!

A landfill rich in biodiversity

What some people might be surprised to find out is that Semakau island has a vibrant ecosystem and rich biodiversity.

Despite the remains of all our trash (our sins) lying beneath the ground’s surface, the island and its surrounding waters are inhabited by wildflowers, seagrass meadows and coral reefs.

Many measures were taken during the landfill’s construction to minimise impact on the environment and to preserve its biodiversity. These include replanting mangroves and transplanting rare corals from Semakau to the Sisters’ Island Marine Park. And once a cell is filled and topped with earth, grass and trees are allowed to take root to form a green landscape.

The landfill is now a haven for over 30 species of birds, and a diverse range of marine species like sea slugs, sea stars, sea cucumbers, crabs and sea anemones.

Semakau Landfill was even open to the public for intertidal walks, so that everyone can enjoy the island’s biodiversity. However, the landfill is currently closed to the public due to the Covid-19 restrictions.

While it seems like your takeaway container might have reached a perfect and beautiful resting place, there’s a catch. Here’s what we hope you take away from this article.

Semakau Landfill isn’t infinite, and with our current rate of waste disposal, it is projected to run out of space by 2035. In 2020 alone, 200,000 tonnes of disposables, equivalent to 400 Olympic-size swimming pools, were thrown away.

Which is why one of Singapore’s goals in the next decade is to reduce its waste by 2030.

This is part of the Singapore Green Plan 2030, a whole-of-government effort, which consists of five key pillars each with specific targets — City in Nature, Sustainable Living, Energy Reset, Green Economy, and Resilient Future.

Under the Sustainable Living pillar, the government aims to make reducing carbon emissions, keeping our environment clean, and saving resources and energy a way of life in Singapore.

One of these targets is to reduce the amount of waste to landfill per capita per day by 20 per cent by 2026, and by 30 per cent by 2030.

National Environment Agency’s (NEA) Youth for Environmental Sustainability (YES) Programme

So how can you help with that? Aside from consuming less disposables like bringing your own reusables, or recycling whatever waste can be recycled, you can support NEA’s Youth for Environmental Sustainability programme (or YES for short). The YES programme supports the Singapore Green Plan 2030’s Sustainable Living pillar, by encouraging active green citizenry by youths.

This initiative aims to encourage youth interest in environmental sustainability throughout the year, in partnership with key community stakeholders. Through the YES programme, you can connect with other passionate youths, and volunteer with non-governmental organisations.

There is also a NEA YES Edition of the Youth Corps Leaders Programme, for those who want to lead projects to make environmental impact within the community, where you can develop your environmental leadership and project management skills.

Find out more about YES here.

This sponsored article by NEA helped the author learn more about what happens to our trash.

Top photo by Ashley Tan and Wikipedia

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.