Here’s the thing. I like my drink as much as any other mildly overworked, socially anxious twentysomething.

But somewhere along the line, as my peers began purchasing finely-aged vintages and using adjectives like oaky and tannic and full-bodied, my palate remained stubbornly unsophisticated.

So when my colleague asked if I’d like to consult a sake expert, I jumped at the chance.

After all, this was my chance to finally become a Cultured Individual™ and impress all my friends. Take that, you losers.

Photo courtesy of JFOODO.

Photo courtesy of JFOODO.

An introduction to sake

First things first, it’s important to understand what sake is. In an effort to not embarrass myself in front of the sake expert, I did a spot of research beforehand.

Originating from Japan, sake is a fermented rice beverage. It’s made from brewing sake rice with water, rice, and yeast.

The final product can comprise as much as 80 per cent water, lending it a generally neutral taste.

According to sake sommelier Adrian Goh, who has sake sommelier certifications from three different sake institutions, sake contains compounds that suppress fishy odours and enhance umami flavours, making it a perfect fit for seafood.

This makes it perfectly suited for Japan, an island which, quite naturally, has a culinary culture immutably linked with seafood.

“It is also a very neutral alcohol, with little astringency and no tannin, so it is very unlikely to clash with any flavours, especially seafood,” Goh added.

(BTW: Tannin is a substance commonly found in red wine that adds a dry, bitter flavour. And now you know.)

Types of sake

Not all sake is built equal.

If, like me, you’ve spent an inordinate amount of time hovering around the sake aisle, trying to make sense of the different flavours — this section is here to put you out of your misery.

First, here’s a quick guide to the numbers:

Alcohol content, or Alcohol by volume (ABV): Sake is generally 15 to 17 per cent alcohol.

Sake Meter Value (SMV), or nihonshu-do: The density of the sake relative to water. Very generally, the higher the number, the drier the sake; the lower the number, the sweeter the sake (although this can be affected by other things like acid content and temperature).

As a guide, +10 or so is quite dry, -4 or so is quite sweet, and +3 or so is neutral.

Rice-polishing ratio: Refers to how much the rice is “polished”, or milled, before being used. Generally, the more it’s polished, the higher the grade of sake.

Based on this category, sake can be organised into three categories: Junmai-shu and Honjozo-shu (lowest), Junmai Ginjo-shu and Ginjo-shu, and Junmai Daiginjo-shu and Daiginjo-shu (highest).

Outside of these variations, there’s also Futsuu-shu — normal sake, the equivalent of table wine if you’re a wine person.

Futsuu-shu constitutes about 80 per cent of all sake made. Like table wine, it’s generally cheaper and less premium, but can nevertheless be perfectly enjoyable.

(The suffix -shu means sake, by the way. Again, and now you know.)

Age: In general, sake is not aged and is best consumed fresh. However, there are exceptions; see koshu in the glossary below.

Confused by the language? Here are a few other terms you might come across on your sake label, and what they mean.

- Shinshu: Freshly-brewed sake. From the current brewing season.

- Koshu: Aged sake. Usually over a year old. Generally darker in colour and has a spicy or roasted aroma.

- Genshu: Undiluted sake. Generally has a higher alcohol content.

- Tezukuri: Handmade sake. Made using traditional methods.

- Namazake: Unpasteurised sake. Has a fresh, lively flavour. Should be stored cold.

- Nama-chozu-shu: Sake that is stored unpasteurised, then pasteurised at bottling.

- Namazume: Sake that is pasteurised after pressing, but not at bottling.

- Kijoshu: Sweet sake made from water and previously-brewed sake.

- Taruzake: Sake that’s stored in a cedar cask, and that consequently has a woody aroma.

- Hiyaoroshi: Newly brewed sake that’s aged over the summer. It’s pasteurised only once, after pressing.

- Nigorizake: Cloudy sake. It’s pressed with coarse mesh, so some solids remain in the product.

Another thing to note — while sake is commonly used to refer to the fermented rice beverage, it can also be used to refer to all alcoholic beverages in general.

So in the sake section of your local Cold Storage or Don Don Donki, you might come across a few other drinks, like shochu and awamori.

The former is the Japanese variant of the better-known Korean soju, and has a generally higher alcohol content from around 25 per cent to as high as 42 per cent or more.

Meanwhile, awamori is indigenous to Okinawa. It’s also a rice beverage, but distilled rather than brewed. Unlike sake, it’s designed to be aged.

Pairing sake with food

Now, let’s talk about the most important part: food.

“When you pair Japanese sake with food, you try to align them to similar sweetness and intensity,” Goh explained.

For instance, acidity and salt will bring out the fruity flavours in Japanese sake. Goh gives the example of sambal stingray, which pairs well with a cloudy sake called nigorizake.

“The high acidity and low alcohol, with the yakult flavour, tames the heat,” Goh said, “and the sourness complements the cincalok (fermented shrimp).”

On the other hand, a richer dish, like salted egg crab, would go better with a Junmai sake — particularly a yamahai-style beverage.

This is because the greater body and lactic acid of a yamahai sake would balance the creaminess and intense umami of the salted egg sauce, he explained.

As a general guide, sake can be divided into five types with regards to pairing:

- “Aromatic”: deeply fragrant, with slight hints of citrus.

- “Smooth and refreshing”: clean aroma

- “Rich”: strong, with full umami

- “Aged”: dry, grassy, nutty fragrance, with lingering umami

- “Sparkling”: newest type, carbonated with umami

Photo courtesy of JFOODO.

Photo courtesy of JFOODO.

Not sure what dishes to start with? Here are three of Goh’s personal favourites:

- Raw oysters. Sake goes particularly well with the multifaceted flavours in oysters: briny, sweet, creamy, and mineral. “I like how sake can bring out more flavours out of the oysters,” Goh said.

Photo courtesy of JFOODO.

Photo courtesy of JFOODO.

- Pulpo gallego (an octopus dish from the Galicia region in northwestern Spain). This dish is tender and topped with smoked paprika. According to Goh, this goes especially well with a heavy-bodied, mature sake.

- Cantonese steamed fish with ginger and spring onion. Sake brings out the subtle flavours of this classic dish while covering up the fishiness, and complements the ginger, soy sauce, and spring onions well. “Steam the fish with sake (the method used for a traditional Japanese dish called sakamushi), and it will go even better together!” Goh suggested.

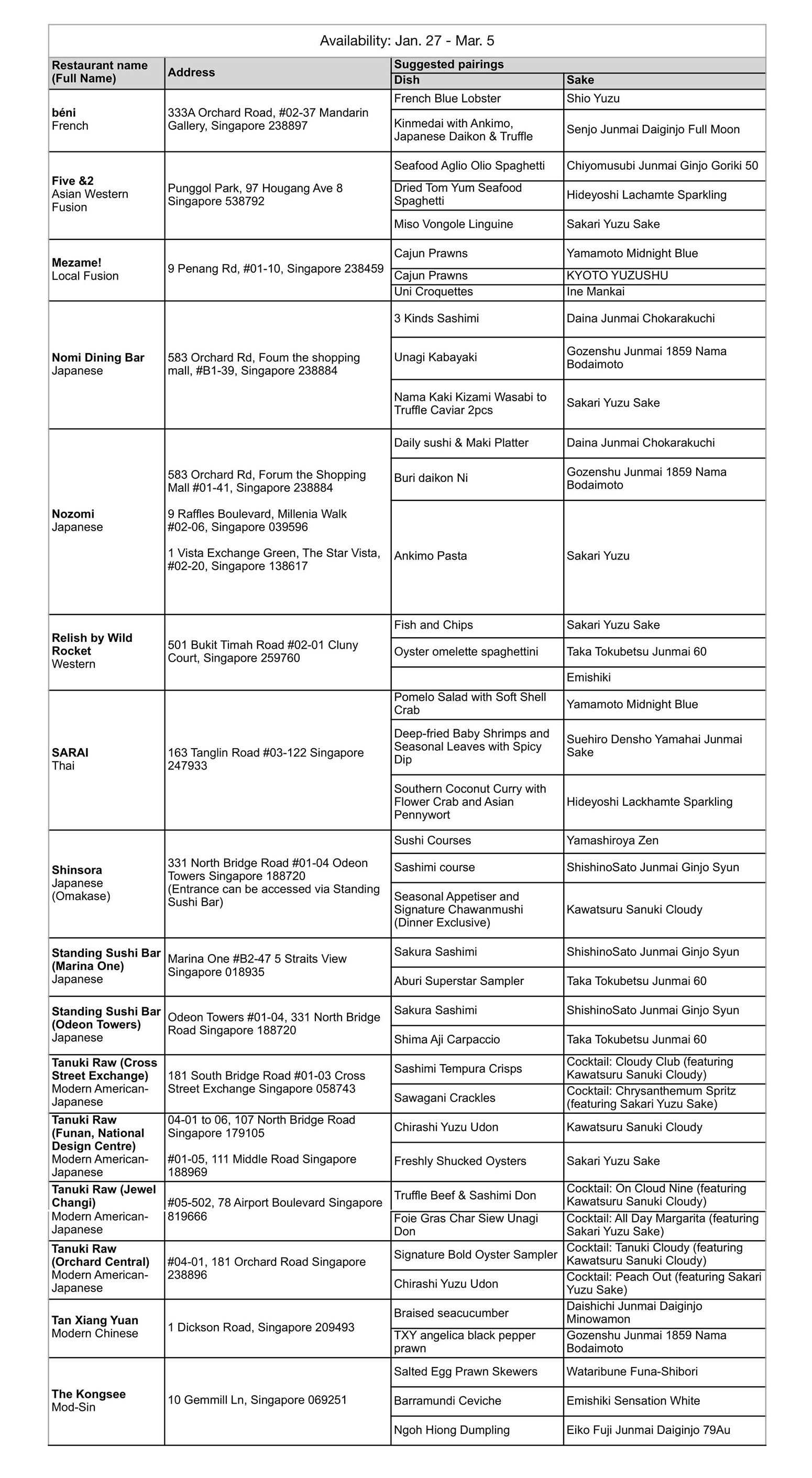

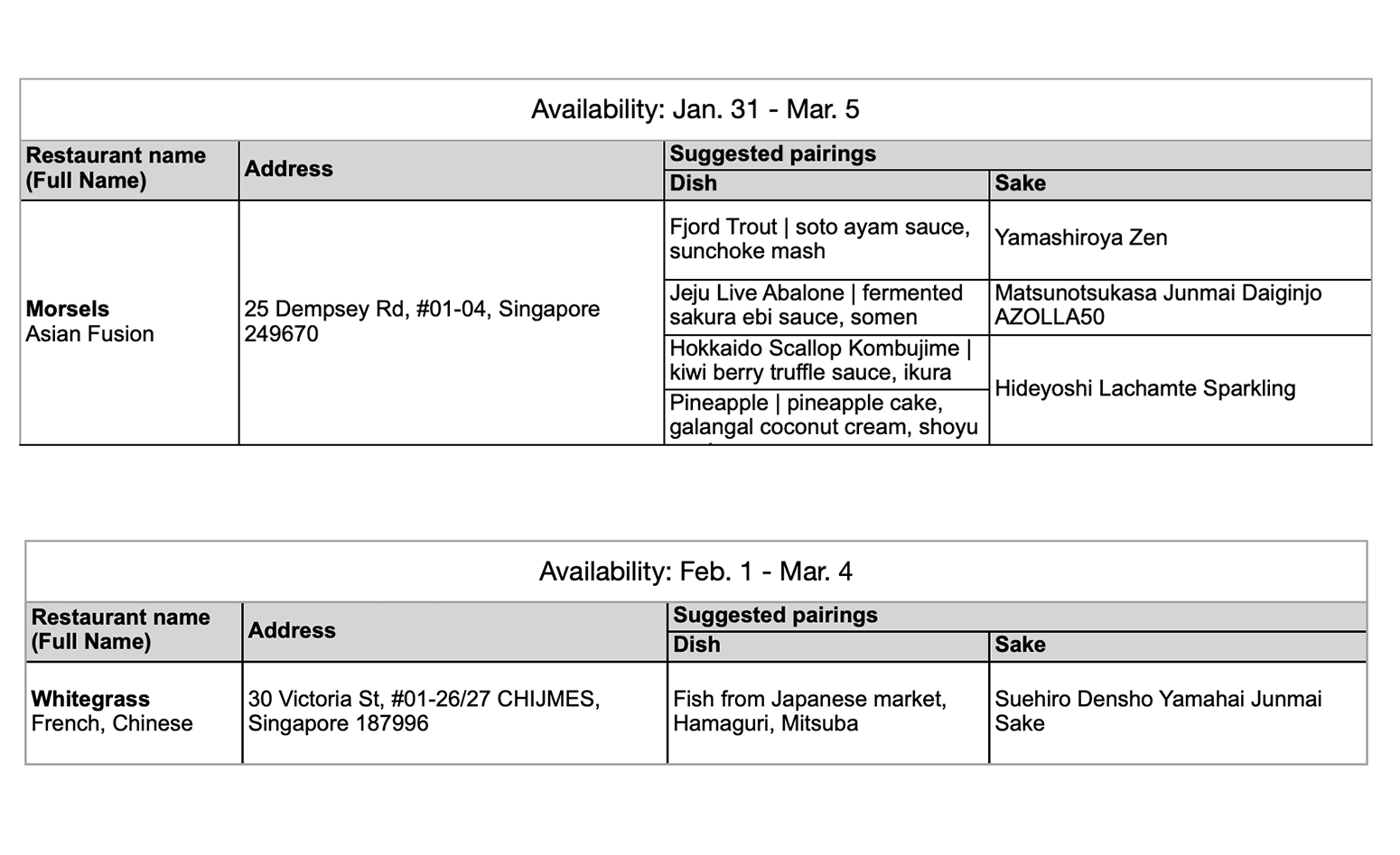

Try it out for yourself

If you’re a fellow aspiring sake connoisseur, you’re in luck.

In collaboration with JFOODO, we’ve prepared a helpful list of restaurants where you can start your sake adventures. Plus some recommendations on how to pair sakes with each restaurant’s dishes, as a bonus.

Don’t feel obliged to restrict yourself to Japanese restaurants, either. In true-blue Singaporean fashion, try pairing it with food from different cuisines (we’ve included a few to start with, like Thai, French, and Chinese).

Learn more about pairing sake and seafood here.

Writing this JFOODO-sponsored article made this writer feel, like, super cultured. Sugoi.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.