A few weeks ago, I visited Changi Prison Complex for the first time.

It was exactly what I’d seen from documentaries; the monolithic structures with tall barbed wire fences, the utilitarian grey and blue walls, the multiple layers of security (we passed through three security checkpoints and eight gates/doors on the way to the assigned interview room at Institution A4).

In that staid, orderly environment, I’m struck by the first word my interviewee thinks of, when asked to describe the prison programme she’s participating in.

“That whole experience was chaotic,” she opens.

It’s the last thing I’m expecting to hear from someone who, from what I’d heard before the interview, was a proud participant with not one but two finished paintings going for public exhibition at Gardens by the Bay this month.

Sarah (not her real name) registers the confusion on my face and quickly explains: The “chaotic” experience came from having to deal with the other inmates who participated in this year’s Yellow Ribbon Community Arts Festival (YR CAF).

“I mean, after I finished my piece, I felt happy.

But during the process, I tell you, there were arguments, there were misunderstandings… Maybe this person used too much paint, then we don’t have [enough], because we [had to] share.”

24-year-old Sarah had to deal with these issues, on top of her struggle with the given theme for the festival: “Home is where the heART is”.

“When they gave us the topic, I was a bit lost,” she says.

Growing up, Sarah spent a number of her formative teenage years in a girl’s hostel, after her parents sought to have her declared “Beyond Parental Control” by the Youth Court.

Things seem to have snowballed from a seemingly small problem: Bullying in school.

Despite being somewhat academically inclined, Sarah explains that these “bullying issues” made her reluctant to attend school.

It wasn’t long before she ended up mixing with the wrong company and got involved with drugs.

“That was like, 2014? I had my first few cases lah. Then after that, parents reported BPC [Beyond Parental Control]. I was under that scheme, and the court put me into a hostel.”

And even while not attending school much, Sarah tells us she managed to sit for exams and somehow meet academic requirements, though her attendance records led to her getting retained several times.

Being placed into a hostel helped Sarah get back to school and continue her studies — including her art studies.

Things changed when she got pregnant, and moved back home after giving birth to her son.

Her parents helped to care for him while she picked up part-time jobs to help make ends meet.

But their relationship remained difficult, with frequent disagreements erupting over the smallest things.

The result of all this?

“I never really found a place that [I’d] call home,” says Sarah.

And so, asked to paint something along the theme of “home” for the prison programme, she was stumped.

“Sometimes I go back to the cell ah, all I think about is my art piece. ‘How ah?’”

High stakes

Sarah is currently detained in a Drug Rehabilitation Centre for treatment and rehabilitation.

Thankfully, her parents are able to care for her son. She shares that her relationship with them has improved since he was born.

It seems like the stakes are higher this time; it’s no longer just her paying the price of youthful rebellion.

But this is Sarah’s third incarceration— and she’s quick to acknowledge how that might influence her parents’ view of her.

“If I’m the parent, I won’t bother so much already. Give up already,” she says with a wry laugh.

There’s also the lingering tension of how her parents were not supportive of her tattoo artist aspirations.

With this as the backdrop, Sarah agreed to join the Arts Behind Bars (ABB) programme even before she got a full idea of what exactly it entailed.

“I just want to be involved in something, you know? Then after that they told me about the Open Visit. ‘Ah, got Open Visit ah? Okay okay okay.’ Then, ‘the art will be displayed.’ ‘Okay okay okay. Can can can, I’ll give it a shot.’”

Programme and platform

ABB, which she’s been involved in for the past few months, is a big part of her third incarceration experience.

It turned out to be a good platform for Sarah, who’s had an interest in art since she was very young.

She went from colouring as a toddler to sketching and drawing, and found her own way into art classes in secondary school.

She then got into tattooing, starting with tattoos for herself, and sometime in 2020, learning the ropes as a tattoo artist.

Art is a medium where she’s clearly comfortable expressing herself, and she clearly treasures the chance to be given a blank canvas.

She remembers fondly a tattoo she did for a customer who was getting over a breakup. Asked to design a tattoo along that theme, she did a fairy with broken, bloodied wings, along with a blooming flower.

The client was pleased with the result, and she was glad for the trust.

Yet, it was a challenge to create art along the theme of “Home is where the HeART is”.

Sarah struggled with the idea of painting “home” when that was a concept she never felt.

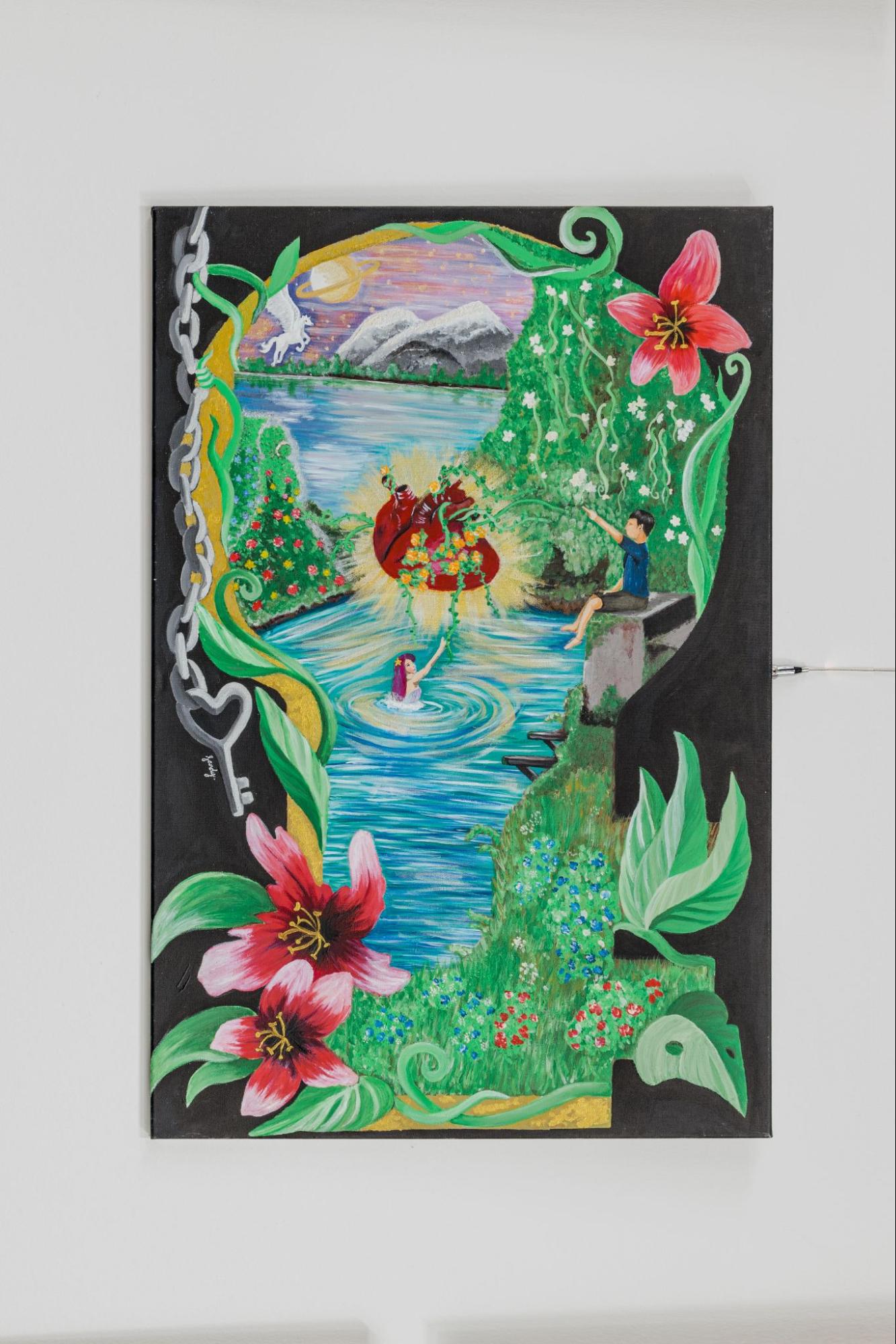

She decided to paint her ideal picture of “home” instead, creating an ethereal fairytale landscape at the banks of a lake or sea, with snow-capped rocky mountains in the background, and a planet and stars in the background.

Two figures — a boy, and a mermaid, representing Sarah and her son — reach out toward each other.

Flowering branches are growing out of an anatomical heart marked with scars, with which Sarah sought to capture the idea of “not giving up, even through all the scars and hardship, life will be coming out of it.”

The entire painting was done from the perspective of someone looking through a keyhole, Sarah’s way of acknowledging that “I haven’t entered there”.

Throughout the conversation, what became very obvious to me was that talking about the art was a much more pleasant way to bring up potentially sensitive topics.

Discussing her art made it easy for me to ask about things like her relationship with her family, without feeling like I was interrogating her about these very personal matters.

The Open Visit

Participants were given the chance to exhibit their finished work to their family and friends at a small private event in October 2022.

“All of us were so nervous,” recalls Sarah. Many had not seen their families for some time.

Plus, the event would be an Open Visit, where the inmates and their families would be meeting face-to-face, without the usual separation (regular visits are done with inmates separated from visitors by a clear screen, or even over video call).

“The nervousness was more towards like, how are we going to react, you know? Am I gonna cry? Are they gonna cry?

We don’t know what to say to our parents, we also don’t know how they would react.”

Sarah was full of anticipation for her parents to finally see the work she’d spent four months on.

“I wanted my parents to see it, because [apart from this], they won’t get a chance already.”

Sarah and the other participants spent the weeks before the show rushing for the deadline, making seemingly endless changes and touch-ups, sometimes to pieces that were already complete except for the artist’s niggling feeling that something could still be improved.

“I can never stop finding errors every day,” said Sarah, who repainted the leaves in her painting 13 times.

“A lot of crying, a lot of emotions”

As it turns out, Sarah had nothing to worry about. Her six-year-old son liked her painting, and could immediately recognise that the figure of a boy in the work represented him.

“I told my son, ‘this one’s you, you know?’” says Sarah, recounting the moment.

“I know! I know it’s me,” came his reply. “Because you love me,” he explained simply.

“My mum was very shocked also, that I can produce such an art piece,” said Sarah.

At the Open Visit, inmates’ families were invited to colour a card which the inmates would then get to keep. Sarah’s six-year-old took to the task with gusto, even drawing a cat with another inmate’s painting as reference. Photos provided by Singapore Prison Service.

At the Open Visit, inmates’ families were invited to colour a card which the inmates would then get to keep. Sarah’s six-year-old took to the task with gusto, even drawing a cat with another inmate’s painting as reference. Photos provided by Singapore Prison Service.

“There was a lot of crying, a lot of emotions,” she recalls of the two-hour visit.

At one point, Sarah and her mom sat down to look at her paintings together.

Sarah’s second piece, titled “100 per cent I”, represents her hope for “home” to be a place where she can be 100 per cent herself.

Sarah’s second piece, titled “100 per cent I”, represents her hope for “home” to be a place where she can be 100 per cent herself.

While there’s a girl with a “sorrowful vibe” in the painting, Sarah stresses that the tears coming out of the eye are meant to be tears of joy.

“This actually represents what home can make me feel. I can be sad, I can be authentic, I can be myself,” she explains.

“Home is a place that gives you happiness also,” she adds, pointing out the building blocks, pacifiers, and milk bottles that represent her son.

“And then the cue ball actually represents my father. Because my father loves playing pool.

And the emojis represents communication with my family members.”

“First time my art is on display and acknowledged by my loved ones,” mused Sarah.

Sarah’s mum is “not a woman of many words”, and said simply, “Wah, zin sui eh” (“Wah, it’s very nice” in Hokkien).

“And that’s when she suddenly sat down to hold my hand. And she said, ‘Actually, you want to do tattoos, can lah. You go out, focus on your tattoo… This time, mummy give you support.”

Sarah, not expecting such a response, remembers feeling “so shocked, but so happy.”

“And so nervous at the same time.”

What’s next for Arts Behind Bars?

With their work for YR CAF now complete, the inmates at Art Behind Bars are now moving on to work on smaller projects, like helping to design conversation cards used by counsellors who work with inmates.

The cards are meant to help counsellors start conversations that centre around key themes relating to rehabilitation, such as relationships, family, bonding, and so on.

One of the conversation cards designed by Sarah features a picture of seashells in a jar, representing the idea of happy memories we pick up and accumulate throughout our lives. Photo via Singapore Prison Service.

One of the conversation cards designed by Sarah features a picture of seashells in a jar, representing the idea of happy memories we pick up and accumulate throughout our lives. Photo via Singapore Prison Service.

Making plans

Sarah says she’s not due to be released till some time in 2024.

She doesn’t want to start counting down just yet but shares that she’s already making plans for when she gets out, realising that life might be passing her by while she’s inside.

Her parents aren’t getting younger, and neither is her son — she’s very conscious that she will not be there when he starts primary school next year.

Perhaps fittingly, Sarah is moving on to a new phase in her own education too, as she plans to start studying for the A Levels in prison next year, to work toward studying English Literature and Art History in university.

And she has big dreams for her career as a tattoo artist as well — she wants to one day be invited to a tattoo expo, start a business, and take on apprentices.

The road ahead for Sarah looks to be a long one, and although she has clear goals in mind, it’s also clear that she will face significant challenges in time to come.

Her aim of going into entrepreneurship as a tattoo artist will bring all the difficulties of doing business: managing finances and risk, finding and keeping clients, and perhaps even taking on staff.

She’ll also have to manage being a single mum to her son, along with the weight of her mum’s expectations, now that her tattoo artist career has received “official” parental approval.

But it’s also clear to see that being involved with art, through her work and the prison’s art programmes, has been a foundation, a platform, and an escape for her — an inextricable part of her story that’s still being told.

Sarah’s art on display at the Colonnade in Gardens by the Bay.

Sarah’s art on display at the Colonnade in Gardens by the Bay.

Yellow Ribbon Community Arts Festival

Themed “Home is where the heART is”, this year’s Yellow Ribbon Community Arts Festival offers a glimpse into the inmates’ ideas of what “home” means to them.

Sarah’s works are among the 50 art pieces on display, created by 14 male inmates from the Visual Arts Hub in Institution B4 of the Changi Prison Complex and 15 women inmates from the Arts Behind Bars programme in Institution A4.

Image via Gardens by the Bay website.

Image via Gardens by the Bay website.

Location: Gardens by the Bay, Colonnade

Date: Nov. 5 (Sat) to Nov. 13 (Sun)

Opening hours: 12pm to 7pm

Admission: Free

This sponsored article by Singapore Prison Service made this writer want to learn to paint.

Top images courtesy of Singapore Prison Service

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.