I have to admit that I had never really given the homeless in Singapore much thought. It’s hard to be invested in something that you hardly see.

In fact, if you were to ask some people for their thoughts on Singapore’s homeless, their response could very well be, “What homeless?”

But of course, they do exist.

The Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) provided assistance to about 290 displaced individuals every year on average between 2016 and 2018.

Some of them do not have places to live in, while others may have a home but cannot return home for various reasons

But if I were to be completely honest, my disregard for the homeless also stems from a slight disdain for them, fanned by my impression that they are dirty, uncouth, and too lazy to work for a home.

After all, when we were young, how many of our parents warned us to study hard or end up sleeping on the streets?

Now having met people who are homeless, I can say with confidence that many of my preconceptions were terribly wrong.

I came to realise, from a day spent at the New Hope Transitional Shelter, that there are various circumstances, some wholly out of one’s control, that lead to homelessness.

But first, more about the shelter.

Located in a quiet Jalan Kukoh neighbourhood, the shelter is run by New Hope Community Services, and is funded by MSF. It offers displaced people a temporary place to stay and pick themselves up, be it through finding a job or a permanent place.

New Hope is part of a collaborative network that brings together community groups, many of whom were already working on the ground, with MSF and other government and social service agencies to reach out to and support rough sleepers.

This network is called PEERS (which stands for Partners Engaging and Empowering Rough Sleepers) and it was officially launched by MSF in July 2019.

The New Hope Transitional Shelter

The shelter is operated out of a handful of units spread out across a HDB block. These units are where the shelter residents stay until they find more permanent housing arrangements.

For most residents, this takes anywhere between six and nine months.

Residents of the New Hope Transitional Shelter stay in units scattered across this HDB block in Jalan Kukoh. Image by Gareth Chew.

Residents of the New Hope Transitional Shelter stay in units scattered across this HDB block in Jalan Kukoh. Image by Gareth Chew.

The unit that I survey is spartan.

The living room has no television or sofa set. It’s furnished with a table, a chair, and an ironing board.

In their rooms, residents sleep on bunk beds and share a small kitchen and a common toilet. If they need to store their belongings, personal metal lockers are available.

The living room of one of the Transitional Shelter’s units. Image by Joshua Lee.

The living room of one of the Transitional Shelter’s units. Image by Joshua Lee.

Residents share a communal kitchen. Image by Joshua Lee.

Residents share a communal kitchen. Image by Joshua Lee.

It is a bit of a squeeze but for many of them, it’s a better alternative to sleeping rough out on the streets.

Here, there is some semblance of normality.

So why do people end up sleeping outside?

For 63-year-old John (not his real name), a shelter resident, he didn’t want to be a burden to his daughter.

John has been living in the shelter for about three months now.

The man talks slowly, and has writing difficulties, not because of his age, but because he is a two-time stroke survivor.

John was a businessman who moved to Boston in 1988. There he got married and had a daughter.

After his marriage broke down, he gained sole custody of his daughter, who is currently studying medicine in an American college.

Unfortunately, his strokes strained his family life. John’s daughter found it hard to juggle her studies with her father’s medical visits, which could be as often as four times a week at different places.

“I found that she could not cope with her studies because I gave her a lot of stress,” he says, his eyes downcast.

“I had to make a decision. I told her I wanted to go to Singapore. It’s better for her and for me. When she cannot see me, she can concentrate on her studies.”

John sold his property and car in America, gave all his money to his daughter and returned to Singapore where, having no house to call his own, he slept at Changi Airport for a month.

“The toilet cleaner became my good friend he helped me a lot. That’s why every time I saw him I gave him S$2 to S$3,” he says with a shy smile.

John only entered the New Hope shelter in July 2019 after he was referred to MSF’s Social Service Office while trying to buy stroke medication at the Singapore General Hospital.

Life in the shelter is simple, much more so than his lifestyle in America. Despite that, he maintains that he is contented with what he has so far.

“I can live a luxurious life,” he says, “I can also live a very poor life.”

Aside from providing shelter, New Hope also helps its residents find jobs. This is important because they need to be financially independent in order to buy or rent their own place.

As you can imagine, John’s job search is made more challenging because of his writing and speaking disabilities but his job coach at New Hope successfully helped him to get a job as a packer at Changi Airport.

It is physically strenuous work for him, but he doesn’t mind.

“I love this job that’s why I don’t really find it hard,” he says because having a roof over his head and a steady job is a much-preferred alternative to sleeping on the streets.

Rita (not her real name), another resident, agrees that living at the shelter is preferable to being out in the streets.

“In the streets you have to look out for public toilets to shower, and keep your things in safes, and places to charge your phone.”

In fact, the 35-year-old gamely teaches me a special (and probably illegal) method of charging your phone (for free, of course) using the automated flushing system in public toilets.

(And no, I’m not going to teach you how to do it.)

Kicked out from uncle’s house

It is life skills like this that Rita picked up after she was kicked out of her uncle’s house.

She initially stayed with her uncle since 2008, after her parents passed away, but he kicked her out after she failed to pay rent for an entire year.

It’s not that she didn’t want to pay, though. Rather, she explains that she cannot hold down a steady job because of her health.

“I have epilepsy and type 1 diabetes,” she reveals.

Diagnosed in 2011, Rita has epileptic seizures which come randomly. They make her black out, at times for hours on end.

Because of that, she had to change jobs three times in 2018 alone. She has also lost count of the number of times she woke up to find bloodstained pillows and floors from her biting her own tongue or falling down from her seizures.

“Over here (at the shelter) it happened twice and they sent me to the hospital,” she says, adding that it appears to be getting worse over the years. “In one week I can get (them) up to three times.”

When her uncle chased her out, Rita, sought help at a Family Service Centre, which referred her to New Hope in July. She also managed to seek financial assistance from MSF’s SSO to cover her daily expenses.

Life has been hard for her and it shows. Throughout our interview, Rita sits with her arms crossed and glares at the world with suspicion.

But she relaxes visibly when talking about her stay at the shelter because, unexpectedly, it is here that she found some semblance of family.

Her flatmates all look out for her because they know of her condition, she says.

Rita is particularly thankful for her roommate Shanti, an elderly lady who cares for her in small ways — reminding her to take her insulin jabs, for instance, and warning her to be careful when the floor is wet.

Sadly, she says this thoughtfulness and affection she saw in Shanti was found wanting in her biological family.

“They needed my help so they used me, and the moment they realised I can’t be made use of, they kicked me out. You know the saying that friends will abandon you but not your family? That’s bullsh*t.”

Thankfully, Rita has found kindred spirits at the shelter, especially Shanti, with whom she is applying for a HDB rental flat under the Joint Singles Scheme now.

Helping shelter residents find a home

Many shelter residents can’t qualify for public housing through the common routes, and that’s where social workers at the shelter come in to help them.

Social worker Peck Sian tells me that it can be a challenge to work out a concrete and sustainable plan with residents, especially those whose situation is complicated by issues such as family disputes and citizenship. In view of this, social workers meet regularly with HDB officers to discuss housing options for the residents.

“Many of these people have been through multiple rejections by the system so they have negative experiences, and it’s very hard to engage them to get them to trust you again,” she says, adding that it takes a lot of time and patience before they are willing to work with case workers.

A social worker helps residents find jobs and permanent accommodation. Image by Gareth Chew.

A social worker helps residents find jobs and permanent accommodation. Image by Gareth Chew.

But it is worth it, says Peck Sian, when the residents finally secure their flats — places they can call their own.

“When you see them moving in, they are so happy getting the place done, buying things for themselves, you realise that it’s good to have journeyed with them.

Homeless and struck with cancer

One such success story is Gary (not his real name), who managed to rent a one-room flat after living at the shelter for four months.

Previously a freelance tailor shuttling between Singapore and Batam, Gary married an Indonesian lady and has two sons with her.

Three and a half years ago, though, he was diagnosed with third stage colon cancer. One and a half years later, his tailoring business failed.

Gary’s life was in shambles but that was not the end. Faced with mounting medical bills and no income, his wife kicked him out of their home in Batam.

“My wife didn’t want me because I didn’t have money anymore,” he says in Mandarin and English, “No income mah, how to support my children?”

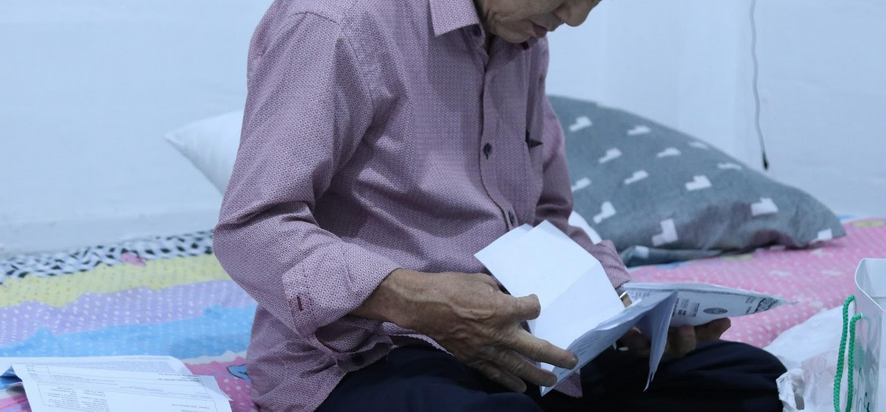

Gary sits on his own mattress in his rented flat. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Gary sits on his own mattress in his rented flat. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Left with nothing, Gary travelled back to Singapore where he found work as a cleaner, but it was short lived. Why? Rolling up his pants, he reveals an ugly patch of mottled skin on his shin.

He has psoriasis — an autoimmune disease that manifests in skin abnormalities.

“People scared contagious so they don't want me,” he says.

With no home to call his own, he spent his nights sleeping rough at Kreta Ayer Square. There were days, he says, that he would go without showering. It was very uncomfortable. For his meals, he would survive on free food offered by Chinese temples.

He was admitted to New Hope in May this year, after being engaged and offered help by volunteers on a night walk.

“It’s better here. Over at Chinatown, whenever it rained, it’s over. I was lucky not to fall sick from being drenched,“ he says.

Gary is still legally married, but wanted to rent a HDB flat as a single because he is estranged from his family.

Gary’s social worker, Peck Sian, worked with HDB to secure him a flat under the Joint Singles Scheme.. Less than two months after submitting his application and documents, he moved into a rental flat with a fellow coffeeshop regular.

“New Hope is very helpful. They’re really good. They help people like us who have no hope,” says Gary.

Gary has a stable job now as a cleaner working at Great World City, which earns him S$45 a day. It’s not much, but he receives cash on a daily basis; that helps with his day-to-day needs.

With his new source of income, he was able to buy a second-hand fan, a washing machine, and a refrigerator to furnish his rental flat.

Inspired by their resilience and tenacity

Having listened to the stories of Gary, John, and Rita, I had to reevaluate my preconceptions about homeless people.

These are people who were displaced, not because of failures on their part but because of circumstances quite beyond their control. After all, no one in their right mind would ask for sickness, or to be kicked out of their family homes.

Ultimately, though, I came away inspired by their resilience and tenacity to survive in the face of such odds and pick themselves up to start life anew.

Homelessness cannot be solved by any one entity. It requires a community effort. In the PEERS Network, like-minded volunteers come together to befriend, engage and build relationships with the homeless, helping them to rebuild their lives.

If you would like to be part of this meaningful experience and make a difference in the lives of homeless persons, you can either join regular night walks with befrienders under PEERS Network to reach out to rough sleepers, or volunteer at New Hope Community Services.

For enquiries on volunteering opportunities with New Hope, you can drop an email to New Hope Community Services. To join the befrienders, email Homeless Hearts of Singapore or Catholic Welfare Services.

This article sponsored by Ministry of Social and Family Development wasn’t easy to work on, but was a very meaningful endeavour the writer found very worthwhile.

Names of the shelter’s residents have been changed to protect their privacy. Top image by Gareth Chew.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.