NRICs are no longer secret. Here's what we don't quite understand yet about this whole thing.

Existential crisis in progress.

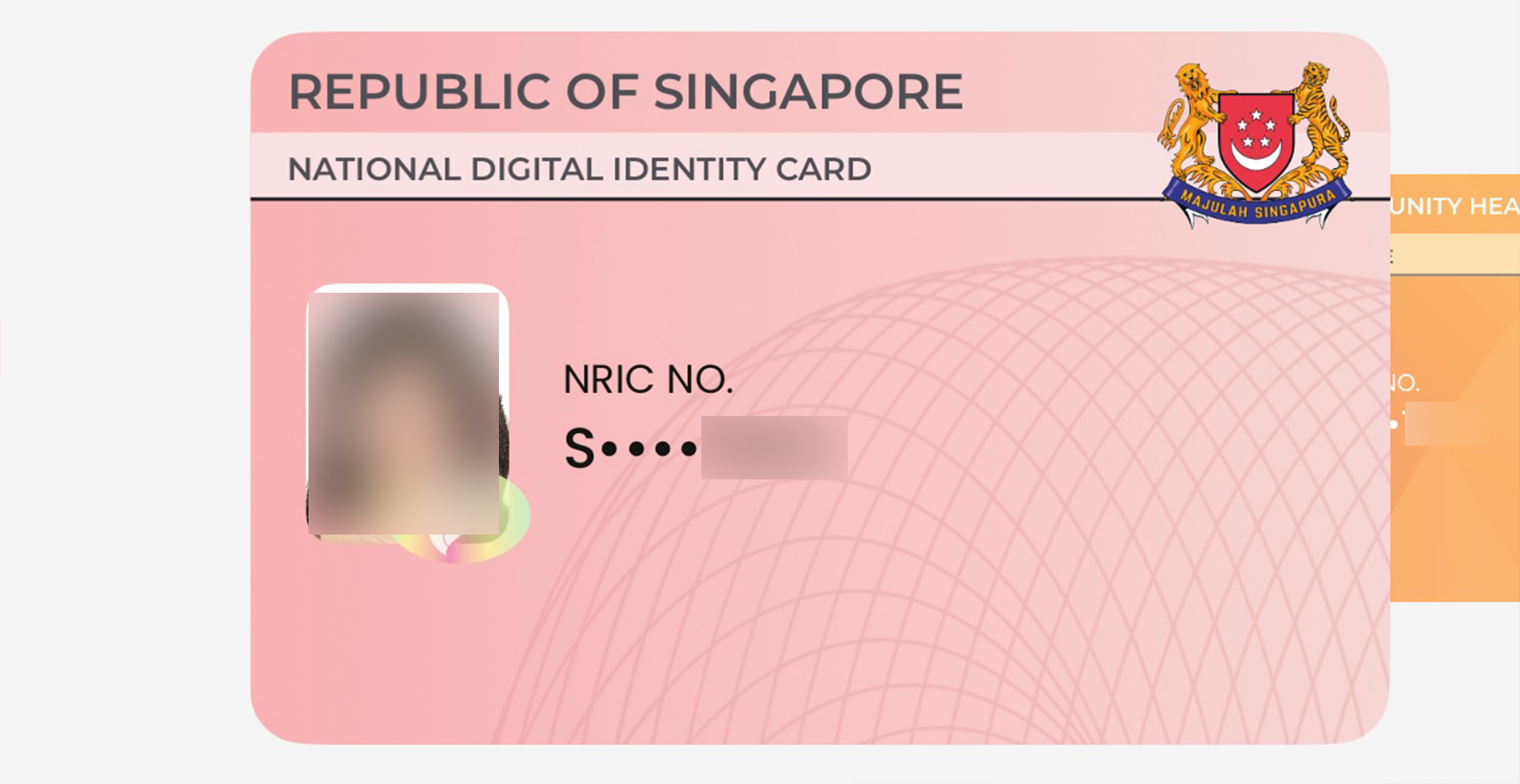

The NRIC number, long considered secret info on par with salaries or secondary-school blogs, has officially been declassified.

In a Dec. 13 statement following the release of many Singaporeans' full NRIC numbers on BizFile, without requiring login or payment, the government confirmed that it was not a mistake — merely ahead of its time.

The plan, said the Ministry of Digital Development and Information (MDDI), is for NRICs to be "used freely as a personal identifier in the same way we use our names".

That's quite a bit to take in. Particularly considering that barely five years ago, the government criminalised improper collection, use, and disclosure of NRIC details by organisations, in the name of data protection.

With that in mind, we have a couple of questions to ask.

When did the government decide to declassify NRICs?

We have a little bit of info as to the why.

In the aforementioned Dec. 13 statement, MDDI explained that NRICs are masked through the usual method — for instance, rendering S0123456A as *****456A.

But MDDI said algorithms can be used to "make a good guess" at the full number.

The ministry added that since the NRIC number is a "unique identifier", it should not also be a means of authentication. An identifier would require the number to be known; if used for authentication, it would need to be kept secret.

Regardless, the when behind their decision to declassify NRIC remains to be understood.

At what point did the NRIC go from sensitive information to being "assumed to be known", equivalent to one's full name?

And why did the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) suddenly move ahead with the new "declassified NRIC" stance, where no other government organisation had gone before?

Which brings us to the second question.

How did ACRA end up unmasking NRICs, ahead of government policy?

In its own statement, ACRA apologised to members of the public for "[moving] ahead with the unmasking before public education on the appropriate use of NRIC information could be done".

In a similar vein, MDDI said that ACRA's move had "run ahead of the government's intent".

Here are the facts. ACRA is a statutory board under the Ministry of Finance; this means it's exempt from the Personal Data Protection Act.

That also means that, legally, it's free to disclose NRIC numbers.

But ACRA being a government organisation also means that it should've acted in line with the previous understanding that NRICs should be kept confidential for data protection purposes (even though we now know the understanding is outdated).

The thinking, as the PDPC explained previously, was this: "indiscriminate collection or negligent handling of NRIC numbers can increase the risk of unintended disclosure and may result in NRIC numbers being used for illegal activities such as identity theft or fraud".

On Dec. 14, the PDPC said that it would update and align its guidelines with the new government stance on NRICs.

Regardless, it's curious how ACRA ended up moving ahead — or "running ahead", in MDDI's terms — with the new policy, before whole-of-government efforts began at all.

Will any safeguards be put in place, since ACRA jumped the gun?

Since Dec. 13, ACRA has temporarily disabled the new feature that allows for public searches of NRIC numbers.

But between that date and the launch of the new platform on Dec. 9, were five chaotic days in which itchy-handed Singaporeans took to the platform to search the NRICs of our fellow Singaporeans.

Ourselves included, of course.

MDDI said it had intended to change the existing practice of masking NRIC numbers only after preparing the ground, and with good reason.

Until now, NRICs are used in everyday life: as both a form of identification (i.e. claiming an identity, akin to saying "I am so-and-so"), and a form of authentication (i.e. proving an identity, akin to providing evidence that you are indeed so-and-so).

Aside from the usage of NRICs in government text messages (like the recent Assurance Package messages), they're used in various settings, from healthcare to banking.

Take registering for an appointment at a polyclinic. To get a queue number, all you need to do is to key your NRIC number into the ticket machine.

With somebody else's NRIC number, you could theoretically make an appointment under someone else's name; attend a consultation while pretending to be them; and access their medications.

And, in all likelihood, bill them for said medications as well. Assuming no one asks for further authentication of your identity.

MDDI said it plans in the coming year to conduct public education efforts about the NRIC number and how it should be used.

But in the meantime, when the NRIC numbers are already out there — possibly in the pockets of bad actors — will any safeguards be taken?

When will the government put this new policy into action?

As the government itself has acknowledged, such a paradigm shift won't happen overnight.

Organisations which rely on NRIC numbers to authenticate individuals’ identities will need other means of doing so instead. So perhaps we'll soon see iris scanners at polyclinics, or fingerprint readers in hospital wards.

And on an individual level, likely it'll take quite an extensive public education campaign, to get everyone, from tech bros to hawker aunties, up to speed.

Will it take roadshows? Door-to-door visits? Catchy NRIC-themed jingles?

It remains to be seen. But it'll surely take time to wrap our heads around of a no-longer-secret NRIC, that will — apparently — be more or less just as sensitive an identifier as our full names.

Imagine: when that day comes, as you read the byline containing my name at the top of a Mothership article, you'd pretty much be handling information that's just as non-confidential as my NRIC.

Just don't go digging around for my secondary-school blog.

Top image by Mothership

MORE STORIES