S’porean student, 23, gets scholarship to study prosthetics & orthotics overseas & help amputee dad

So wholesome.

Chong Jun Xiang, 23, is your typical Singaporean student.

He enjoys sports and cooking. His best subjects are math and science. Now, he’s studying abroad in Scotland.

Unlike his peers, however, Chong is studying something that not many have heard of: Prosthetics & Orthotics, or P&O for short.

He was inspired by his father, an above-the-knee (AK) amputee, who lost his leg when Chong was seven years old.

Today, Chong is a final -year student at the University of Strathclyde, supported by the Healthcare Merit Award, offered by MOH Holdings. He hopes to better his dad’s quality of life, as well as help people with similar conditions.

We spoke to him to find out more about what it’s like pursuing this little-known field that means so much to him.

Tell us about yourself.

I’m Jun Xiang, a fourth-year P&O student at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow.

I decided to pursue P&O since my polytechnic years, when I studied biomedical engineering.

There are a few reasons why I chose P&O. Firstly, I wanted to play to my strengths: mathematics and science.

Secondly, my dad is a transfemoral amputee. Basically, his leg has been amputated up to the mid-thigh area.

He got into a road traffic accident when I was about seven years old, I can’t really remember because I was quite young.

I grew up with him using different prosthetic devices. I saw some of his struggles and complaints with living with a prosthesis.

What sort of struggles?

One of his complaints is that he has multiple pressure sores when walking long distances. He also gets tired very easily.

One time, we were travelling overseas, and I was in charge of the itinerary. I had planned an itinerary that included lots of walking unaware that it would cause struggles to my dad.

Photo from Jun Xiang

Photo from Jun Xiang

After some walking, he mentioned feeling a pain that none of the family members understood. But then he showed us his wounds, and we were quite shocked. The socket device that he was wearing caused some abrasion.

So this inspired me to create a customised prosthetic device for him, to basically better his quality of life.

This got me thinking that if my dad has these issues, I’m sure other amputees out there in Singapore will share the same struggles.

And I really hope this is something I can help them with, to be able to walk comfortably, just like any person.

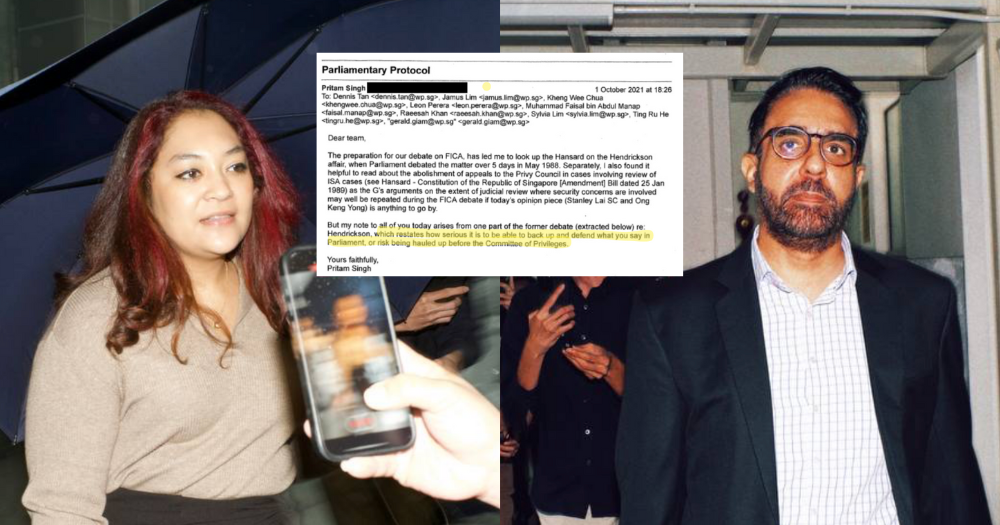

What is it like studying P&O?

Prosthetics involves fitting an artificial body part (mostly limbs) for people with limb differences.

Orthotics involves external braces fitted to people to support or correct the function of a limb or the torso.

Currently, we are learning the fundamentals — everything from prosthetic devices for both the upper and lower limb, and orthotic devices for the upper and lower limb as well as the torso.

This includes learning human anatomy, biomechanics, patient assessment, and so on.

Eventually, I hope to explore more about transfemoral prosthetic devices.

It’s one of the less-seen focuses because there are not a lot of people with AK amputation as compared to below-the-knee (BK) amputation.

In addition, due to the proximity of AK amputation, fitting a prosthesis generally tends to be trickier and more difficult.

Because of that, more medical research has been conducted in this area recently. I thought I could look more into that, and perhaps contribute in the future.

Photo from Jun Xiang

Photo from Jun Xiang

What is it like treating patients?

So during our clinicals, we see patients that come in from the UK’s National Health Service (NHS).

We talk to them, assess them, and prescribe them with a prosthetic or orthotic device.

My favourite part is listening to their stories. For example, when they tell me how they want to walk their dog, or how they want to kneel down to play with their grandkids.

These kinds of stories make me want to help them even more, as it enables them to enjoy life like anybody else.

I remember one patient who had a stroke and was unable to walk well. The orthotic device he had was hurting him because it wasn’t very well done.

So, what we did was to cut out the rivets that were probing the skin, and smooth the area.

We could not create a new device, so we sought to mitigate the damage.

The patient was really grateful. He was just thanking us so much for helping him to walk again.

You mentioned wanting to improve prosthetic devices. Could you share more about how?

It’s quite interesting because it’s actually one of my thesis projects.

There are two different types of prosthetic devices.

One is a socket design that you fit the limb into the socket. Like putting a mop in a bucket.

Another type is called osseointegration, when you have a titanium rod fitted inside the thigh bone and fused.

It sounds quite gruesome. But it’s one of the latest procedures out there because it eliminates all the socket-type fitting issues, like pressure sores and discomfort.

So I’m looking a lot into osseointegration. It’s very new and quite intrusive, but it’s one of the procedures that I’m looking into for my dad.

Photo from Jun Xiang

Photo from Jun Xiang

Did you always want to study P&O?

When I was young, I liked to cook, so I wanted to be a chef. (laughs)

I only started thinking about [P&O] because of my dad.

Funny thing — I applied for this scholarship not knowing that I had to study abroad.

I thought it was under the faculty of biomedical engineering, and that I could do it in NTU (Nanyang Technological University) or NUS (National University of Singapore).

It was after I did my research that I realised it was only available overseas. And that was a major consideration, because it meant adapting to a whole new environment for a duration of four years.

But I felt this is something I had to do.

How has it been since?

It’s quite tough because of the eight-hour time difference with Singapore.

So, when I’m awake, my friends and family back in Singapore are sleeping and vice versa.

For family, I try to contact them as much as I can. In my first year it was every day, then every two days, then every three days.

Now I contact them once a week if time permits. (laughs)

With my friends, it’s similar. I try to maintain contact, but it’s honestly very difficult. When I message [them] they’re sleeping, when they message me, I’ll be sleeping.

Then we lose track of the conversation due to time differences.

Photo from Jun Xiang

Photo from Jun Xiang

Also, being independent is a whole new ballgame. I have to cook, do grocery shopping, and study at the same time. Not to mention living in a different jurisdiction, managing finances and administration.

I like cooking so that part is not so bad. I’m living with some Singaporeans, and some of them really dislike cooking.

So I can see that it’s almost like torture every time they have to cook and go grocery shopping. (laughs)

What are your plans for the future?

After I graduate, I’ll be serving out my scholarship bond at Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH).

My time here has truly helped me appreciate Singapore more. When we’re here, we lose track of all the festivities, because nobody here celebrates them.

Sometimes I don’t even know that it’s Chinese New Year.

I also plan to treat my dad. Actually I’m not sure if I can treat him because of ethical and professional considerations, but I can observe other clinicians helping him.

I’m a family member so when I tell him things he won’t believe it.

He has told me that he wants to stop walking. Even for my graduation next year, he was telling me he wanted to attend the ceremony in a wheelchair.

It’s quite disheartening for me, because I’m trying very hard to get him to walk.

But I’m trying to do whatever I can.

Photo from Jun Xiang

Photo from Jun Xiang

Do you think that your dad will really turn up at your graduation in a wheelchair?

I think he’ll walk. Because I’ll force him to. (laughs)

I’ll say I don’t care, you better walk when you come. So you prepare yourself.

Because I feel I tried so much, the entire time I’m pursuing this course, it’s just for him to walk better.

So maybe he says he’ll come in a wheelchair, but he’s just teasing me lah, I hope.

You’re going into your final year of studies. How do you feel about starting work?

Last summer, I went back for my clinical attachment in TTSH where I followed clinicians for three weeks.

I wasn’t even the one doing the prescription or the patient interaction. I was just observing, but that itself took quite a bit of getting used to.

Because by observing, I still had to use a lot of brain power to associate theory and practical with real-life situations, which was quite tiring.

For the first three weeks, I found myself repeating the cycle of waking up, going to work, and coming back home to sleep.

From what I have learned so far, completion of my Bachelor’s is just the starting point of my P&O journey.

I understand that I still have a lot to learn even after finishing my studies.

Sure, this journey is going to be tough and tiring, but I am sure it is going to be fulfilling. I am already looking forward to starting work and learning from experienced clinicians in my centre.

It’s a bit cliched, but I firmly believe that those who are happiest are those who do most for others.

Photo from Jun Xiang

Photo from Jun Xiang

Writing this Healthcare Scholarships-sponsored article reminded the writer to be grateful for the healthcare workers who care for us every day.

Top image via Jun Xiang

MORE STORIES